Chapter 900 : 5 12/22/2014

COMPENDIUM: Chapter 900

Visual Art Works

901 What This Chapter Covers

This Chapter covers issues related to the examination and registration of visual art works. Visual art works include a wide variety of pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works and architectural works, which are discussed in more detail below.

- For a general overview of the registration process, see Chapter 200.

- For a general discussion of copyrightable authorship, see Chapter 300.

- For a discussion of who may file an application, see Chapter 400.

- For guidance in identifying the work that the applicant intends to register, see Chapter 500.

- For guidance in completing the fields/spaces of a basic application, see Chapter 600.

- For guidance on the filing fee, see Chapter 1400.

- For guidance on submitting the deposit copy(ies), see Chapter 1500.

The U.S. Copyright Office uses the term “visual art works” and “works of the visual arts” to collectively refer to the types of works listed in Sections 903.1 and 903.2 below. This Chapter does not discuss “works of visual art,” which is a specific class of works that are eligible for protection under the Visual Artists Rights Act. See 17 U.S.C. § 101 (definition of “work of visual art”), 106A. For a definition of this term and for information concerning the Visual Arts Registry for such works, see Chapter 2300, Section 2314.

Likewise, this Chapter does not discuss the registration and examination of mask works or vessel designs, which are examined by the Visual Arts Division of the U.S. Copyright Office. For information on the registration and examination of mask works, and vessel designs, see Chapters 1200 and 1300.

902 Visual Arts Division

The U.S. Copyright Office’s Visual Arts Division (“VA”) handles the examination and registration of all visual art works. The registration specialists in VA have experience reviewing a variety of visual art works and specialize in these particular types of work.

903 What Is a Visual Art Work?

For purposes of registration, the U.S. Copyright Office defines visual art works as (i) pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works, and (ii) architectural works.

Chapter 900: 6 12/22/2014903.1 Pictorial, Graphic, and Sculptural Works

The most common types of visual art works are pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works. These types of works include:

- Fine art (e.g., painting and sculpture).

- Graphic art.

- Applied art (e.g., art applied to an article).

- Photographs.

- Prints and art reproductions.

- Maps, globes, and other cartographic materials.

- Charts and Diagrams.

- Models.

- Technical drawings, including architectural plans.

- Works of artistic craftsmanship (e.g., textiles, jewelry, glassware, table service patterns, wall plaques, toys, dolls, stuffed toy animals, models, and the separable artistic features of two dimensional and three dimensional useful articles).

17 U.S.C. § 101 (definition of “pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works”). For information concerning specific types of pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works, see Sections 908 through 923.

Congress made it clear that pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works are subject to an important limitation, namely that useful articles and functional elements of pictorial, graphic, and sculptural works are not copyrightable unless they are physically or conceptually separable from the functional or useful elements of the work. For a definition and discussion of “useful articles,” see Section 924.

903.2 Architectural Works

The Copyright Act protects certain architectural works, which are defined as “the design of a building as embodied in any tangible medium of expression, including a building, architectural plans, or drawings.” 17 U.S.C. § 101. An architectural work “includes the overall form as well as the arrangement and composition of spaces and elements in the design, but does not include individual standard features.” Id. For detailed information concerning architectural works, see Section 923.

904 Fixation of Visual Art Works

A visual art work must be “fixed” in a “tangible medium of expression” to be eligible for copyright protection. 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). The authorship may be new or may consist of Chapter 900: 7 12/22/2014 registrable derivative authorship. The basic requirement is that the work must be embodied in some form that allows the work to be “perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated for a period of more than a transitory duration.” 17 U.S.C. § 101 (definition of “fixed”). The U.S. Copyright Office will register visual art works that are embodied in a wide variety of forms, including:

- Canvas.

- Paper.

- Clay.

- Stone.

- Metal.

- Prints.

- Collages.

- Photographic film.

- Digital files.

- Holograms and individual slides.

- Art reproductions.

- Diagrams, patterns, and models.

- Constructed buildings or models depicting an architectural work.

This is not an exhaustive list and the Office will consider other forms of embodiment on a case-by-case basis. In particular, architectural works do not have to be constructed to be eligible for copyright protection.

While most visual art works are fixed by their very nature (e.g., a sculpture, a painting, or a drawing), there are some works that may not be sufficiently fixed to warrant registration. Specifically, the Office cannot register a work created in a medium that is not intended to exist for more than a transitory period, or in a medium that is constantly changing.

Most visual art works satisfy the fixation requirement, because the deposit copy(ies) or identifying material submitted with the application usually indicate that the work is capable of being perceived for more than a transitory duration. However, the fact that uncopyrightable material has been fixed through reproduction does not make the underlying material copyrightable. For example, a photograph of a fireworks display may be a copyrightable fixation of the photographic image, but the fireworks themselves do not constitute copyrightable subject matter. Similarly, a textual description of the Chapter 900: 8 12/22/2014 idea for a painting may be a copyrightable fixation of the text, but it is not a fixation of the painting described therein.

As a general rule, applicants do not have to submit an original or unique copy of a visual art work in order to register that work with the Office. In most cases, applicants may submit photographs or other identifying materials that provide the Office with a sufficient representation or depiction of the work for examination purposes.

When completing an application, applicants should accurately identify the work that is being submitted for registration, particularly when submitting identifying material. For example, if the applicant intends to register a sculpture and submits a photograph of the sculpture as the identifying material, the applicant should expressly state “sculpture” in the application. Otherwise, it may be unclear whether the applicant intends to register the photograph or the sculpture shown in the photograph.

Before submitting identifying material for a published visual art work, applicants should consult the best edition requirements, which are listed in the “Best Edition Statement” set forth in Appendix B to Part 202 of the Office’s regulations. The Best Edition Statement is also posted on the Office’s website in Circular 7B: Best Edition of Published Copyrighted Works for the Collections of the Library of Congress (www.copyright.gov/circs/circ07b.pdf). For specific deposit requirements for different types of visual art works, see Chapter 1500, Section 1509.3.

905 Copyrightable Authorship in Visual Art Works

The U.S. Copyright Office may register a visual art work (i) if it is the product of human authorship, (ii) if it was independently created (meaning that the work was not merely copied from another source), and (iii) if it contains a sufficient amount of original pictorial, graphic, sculptural, or architectural authorship. The Office reviews visual art works consistent with the general principles set forth in Chapter 300 (Copyrightable Authorship: What Can Be Registered), as well as the guidelines described in this Chapter.

In the case of two-dimensional works, original authorship may be expressed in a variety of ways, such as the linear contours of a drawing, the design and brush strokes of a painting, the diverse fragments forming a collage, the pieces of colored stone arranged in a mosaic portrait, among other forms of pictorial or graphic expression.

In the case of three-dimensional works, original authorship may be expressed in many ways, such as carving, cutting, molding, casting, shaping, or otherwise processing material into a three-dimensional work of sculpture.

Likewise, original authorship may be present in the selection, coordination, and/or arrangement of images, words, or other elements, provided that there is a sufficient amount of creative expression in the work as a whole.

In all cases, a visual art work must contain a sufficient amount of creative expression. Merely bringing together only a few standard forms or shapes with minor linear or spatial variations does not satisfy this requirement.

Chapter 900: 9 12/22/2014The Office will not register works that consist entirely of uncopyrightable elements (such as those discussed in Chapter 300, Section 313 and Section 906 below) unless those elements have been selected, coordinated, and/or arranged in a sufficiently creative manner. In no event can registration rest solely upon the mere communication in two- or three-dimensional form of an idea, method of operation, plan, process, or system. In each case, the author’s creative expression must stand alone as an independent work apart from the idea which informs it. 17 U.S.C. § 102(b).

For more information on copyrightable authorship, see Chapter 300 (Copyrightable Authorship: What Can be Registered).

906 Uncopyrightable Material

Section 102(a) of the Copyright Act states that copyright protection only extends to “original works of authorship.” 17 U.S.C. § 102(a). Works that have not been fixed in a tangible medium of expression, works that have not been created by a human being, and works that are not eligible for copyright protection in the United States do not satisfy this requirement. Likewise, the copyright law does not protect works that do not constitute copyrightable subject matter or works that do not contain a sufficient amount of original authorship.

The U.S. Copyright Office will register a visual art work that includes uncopyrightable material if the work as a whole is sufficiently creative and original. Some of the uncopyrightable elements that are commonly found in visual art works are discussed in Sections 906.1 through 906.8 below. For a general discussion of uncopyrightable material, see Chapter 300, Section 313.

906.1 Common Geometric Shapes

The Copyright Act does not protect common geometric shapes, either in two- dimensional or three-dimensional form. There are numerous common geometric shapes, including, without limitation, straight or curved lines, circles, ovals, spheres, triangles, cones, squares, squares, cubes, rectangles, diamonds, trapezoids, parallelograms, pentagons, hexagons, heptagons, octagons, and decagons.

Generally, the U.S. Copyright Office will not register a work that merely consists of common geometric shapes unless the author’s use of those shapes results in a work that, as a whole, is sufficiently creative.

Examples:

- Geoffrey George creates a drawing depicting a standard pentagon with no additional design elements. The registration specialist will refuse to register the drawing because it consists only of a simple geometric shape.

- Georgina Glenn painstakingly sculpts a perfectly smooth marble sphere over a period of five months. The registration specialist will refuse to register this work because it is a common geometric shape

and any design in the marble is merely an attribute of the natural stone, rather than a product of human expression.

- Grover Gold creates a painting of a beach scene that includes circles of varying sizes representing bubbles, striated lines representing ocean currents, as well as triangles and curved lines representing birds and shark fins. The registration specialist will register the claim despite the presence of the common geometric shapes.

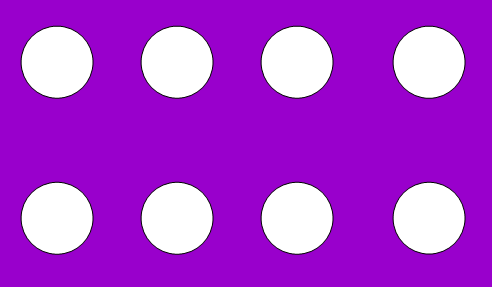

Gloria Grimwald paints a picture with a purple background and evenly spaced white circles:

The registration specialist will refuse to register this claim because simple geometric symbols are not eligible for copyright protection, and the combination of the purple rectangle and the standard symmetrical arrangement of the white circles does not contain a sufficient amount of creative expression to warrant registration.

Gemma Grayson creates a wrapping paper design that includes circles, triangles, and stars arranged in an unusual pattern with each element portrayed in a different color:

Chapter 900: 11 12/22/2014

Chapter 900: 11 12/22/2014

The registration specialist will register this claim because it combines multiple types of geometric shapes in a variety of sizes and colors, culminating in a creative design that goes beyond the mere display of a few geometric shapes in a preordained or obvious arrangement.

- Francis Ford created a sketch of the standard fleur de lys design used by the French monarchy. The registration specialist may refuse to register this claim if the work merely depicts a common fleur de lys.

- Samantha Stone drew an original silhouette of Marie Antoinette with a backdrop featuring multiple fleur de lys designs. The registration specialist may register this work because it incorporates an original, artistic drawing in addition to the standard fleur de lys designs.

- Cleo Camp took a photograph of a tree and digitally edited the image to add new shades of red and blue. Cleo submitted an application to register the altered photograph and described her authorship as “original photograph digitally edited to add new shades of blue and red in certain places.” The registration specialist will register the claim because the creativity in the photograph, together with the alteration of the colors, is sufficiently creative.

- Charles Carter took a digital image of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa and added different hair color, colored nail polish, stylized clothing, and darkened skin. Charles submitted an application to register the image, and described his authorship as “changed public domain Mona Lisa to green and pink streaked hair; purple nail polish; prisoner-striped black-white clothing; and darkened rouge on cheeks.” The registration specialist will register the work because the changes in color are sufficient to constitute a new work of authorship.

- Clara Connor found a black and white photograph that is in the public domain. She altered the image by adding a variety of colors, shades, and tones to make it appear as if the photo was taken in a different season. Clara submitted an application to register the revised photograph and in the Author Created and New Material Included fields she described her authorship as “adapted public domain black-white image by adding different colors, shades, tones, in various places of derivative work.” The registration specialist may register the work if Clara made sufficient changes to the preexisting photograph.

- Chris Crisp purchased a coloring book and colored the images with watercolors. He submitted an application to register the work and described his authorship in the Author Created and New Material Included fields as “added selected colors to pictures in someone else’s coloring book.” The registration specialist may refuse to register the work if the changes were dictated by the coloring book and the addition of color was not sufficiently creative.

- Colette Card registered a fabric design called “Baby Girl Fabric,” which contains a pink background with stylized images of cribs, rattles, and pacifiers. Colette then created a fabric design called “Baby Boy Fabric” that is identical to the “Baby Girl Fabric” design, except that the background color is blue instead of pink. Colette attempts to register the “Baby Boy Fabric,” disclaiming the prior registration for the “Baby Girl Fabric.” The registration specialist

- Felicia Frost creates a font called “Pioneer Living” with embellishments that evoke historical “Wanted: Dead or Alive” posters. The registration specialist will refuse to register this font because it is a utilitarian method of writing without any separable elements that are copyrightable.

- Calliope Cash creates a textile fabric consisting of horizontally striped grass cloth with a pale blue background and characters painted in standard, unembellished Chinese calligraphy. The registration specialist will refuse to register this fabric design because the calligraphy consists of standard Chinese characters, and the mere addition of horizontal stripes or the choice of grass cloth does not add sufficient creativity to warrant registration.

- Pictorial or graphic elements that are used to decorate uncopyrightable characters may be registrable, provided that the elements are separable from the utilitarian form of the characters. Examples include original pictorial art that forms the entire body or shape of the typeface characters, such as a representation of an oak tree, a rose, or a giraffe that is depicted in the shape of a particular letter. In these cases, the representational art may be conceptually separable from the useful function of the typeface.

- Typeface ornamentation that is separable from the typeface characters is almost always an add-on to the beginning and/or ending of the characters. To the extent that such flourishes, swirls, vector ornaments, scrollwork, borders and frames, wreaths, and the like represent works of pictorial authorship in either their individual designs or patterned repetitions, they may be protected by copyright. However, the mere use of text effects (including chalk, popup papercraft, neon, beer

- Loretta Leonard published a series of books on bird watching. Each book has a two-inch right margin and a half-inch left margin, with the text appearing in two columns of differing lengths. Loretta submits an application to register the template for this layout. The registration specialist will refuse to register this claim because the layout of these books does not contain a sufficient amount of originality to be protected by copyright law.

- Fred Foster publishes a one-page newsletter titled Condo Living that provides information for residents of his condominium complex. Each issue contains the name of the newsletter, a drawing of the sun rising over the complex, two columns reserved for text, and a box underneath the columns reserved for photographs. Fred attempts to register the layout for his newsletter. The registration specialist will reject the claim in layout, but may register the illustration if it is sufficiently creative.

- Megan Mott developed linoleum flooring with a random confetti design. The design was created by a purely mechanical process that randomly distributed material on the surface of the linoleum. The registration specialist will refuse to register this design because it was produced by a mechanical process and a random selection and arrangement.

- Nina Nine found a piece of driftwood that was smoothed by ocean currents. She carved an intricate seagull design in the side of the driftwood, polished it, and submitted an application to register the overall work. Although there is no human authorship in the driftwood itself, the registration specialist may register the seagull carving if it is sufficiently creative.

- Felipe French found a stone with deep grooves. Felipe brought the stone to his studio, polished it, mounted it on a brass plate, and submitted it for registration. The registration specialist will refuse registration because the stone’s appearance was the result of a naturally occurring phenomenon and the mounting was merely de minimis.

- Natalia Night creates a sticker made of two clear plastic sheets bonded together with a small amount of colored liquid petroleum between the sheets. Due to the way petroleum naturally behaves, any slight pressure on the outside of the sticker creates undulating patterns and shapes, no two of which are ever identical. The registration specialist will refuse to register this sticker because the specific outlines and contours of the patterns and shapes formed by the liquid petroleum were not created by Natalia, but instead were created by a naturally occurring phenomenon.

- Sculptures based on drawings.

- Drawings based on photographs.

- Lithographs based on paintings.

- Books of maps based on public domain maps with additional features.

- Photocopies and digital scans of works.

- Mere reproductions of preexisting works.

- Theresa Tell creates a collage that combines her own artwork with logos from a number of famous companies. She files an application to register her “two-dimensional artwork.” Depending on the facts presented, the registration specialist may ask the applicant to exclude the logos from the claim by stating “preexisting logos incorporated” in the Material Excluded field. In addition, the specialist may ask Theresa to limit her claim by stating “selection and arrangement of preexisting logos with new two-dimensional artwork added” in the New Material Included field.

- Janine Jackson creates a brooch consisting of three parallel rows of sapphires. The registration specialist will refuse registration because the design is common and there is only a de minimis amount of authorship in the arrangement of stones.

- Jeremiah Jones creates a necklace consisting of a standard cross on a black silk cord with a silver clasp. The registration specialist will refuse to register this work because it consists of functional elements (e.g., a silk cord and a silver clasp) and a familiar symbol (the standard cross).

- The shapes of the various elements (e.g., gemstones, beads, metal pieces, etc.).

- Chapter 900: 19 12/22/2014 The use of color to create an artistic design (although color alone is generally insufficient).

- Decoration on the surface of the jewelry (e.g., engraved designs, variations of texture, etc.).

- The selection and arrangement of the various elements.

- Faceting of individual stones (i.e., gem-cutting).

- Purely functional elements, such as a clasp or fastener.

- Common or symmetrical arrangements.

- The Office receives ten applications, one from each member of a local photography club. All of the photographs depict the Washington Monument and all of them were taken on the same afternoon. Although some of the photographs are remarkably similar in perspective, the registration specialist will register all of

- Phoebe Pool takes a picture of a mountain range, selecting the angle, distance, and lighting for the picture. The registration specialist will register the work even though the mountain range itself is not copyrightable.

- Pamela Patterson takes a high resolution picture of Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. She intends to create an exact replica of the painting, and the photograph is virtually identical to the painting. The registration specialist will refuse to register the photograph, because it is a slavish copy of a work that is in the public domain. See, e.g., Bridgeman Art Library, Ltd. v. Corel Corp., 36 F. Supp. 2d 191, 196-97 (S.D.N.Y. 1999).

- Sarah Smith discovers a box of old family photographs in her great- grandmother’s attic. She scans them into her computer and uses software that automatically smoothens the creases in the images. Sarah files an application to register the altered photographs. The registration specialist will refuse to register these works, because the use of automated software to smooth preexisting photographs was de minimis.

- Dave Daniel submits an application claiming “photograph and two- dimensional artwork.” The registration specialist asks Dave to clarify the nature of the two-dimensional artwork that he contributed to this work. Dave explains that he took a photograph and then digitally touched up several parts of his image. He also explains that he improved the color, tone, and temper; removed noise imperfections inherent in the film; and adjusted aspects to balance the photograph. The specialist will register the claim in the “photograph,” because this term accurately describes the photograph and the authorship involved in editing the original image. The specialist will ask for permission to remove the claim in “two-dimensional artwork” because the work contains no additional artwork aside from the photograph itself.

- Gloria Glam files an application to register a new board game. In her application she asserts a claim in “text and board artwork.” The game board contains intricate designs and the instructions consist of two pages of text. The registration specialist will register the claim.

- Garfield Grant files an application for a new type of soccer playing field. The deposit material contains text and a set of technical drawings. The registration specialist will refuse to register the playing field itself, but will register the drawings and text that describe the field. The registration will extend only to the actual descriptive text and drawings and not to the design for the field itself.

- Glenn Garner files an application to register a “new game of chess, consisting of a new way to play the game, new playing pieces, and a new board with three levels.” The registration specialist may register any descriptive text and the design of the playing pieces if they contain a sufficient amount of creative expression. However, the specialist will refuse to register the idea for and method of playing the new game, as well as the idea of playing the game on a board split into three levels.

- Charles Crest creates a sketch of a field mouse with a straw hat and a mischievous grin. He intends to use the sketch in an animated film. He files an application that asserts a claim in “two-dimensional artwork” and “character.” The registration specialist may ask Charles to limit the claim to the artwork and to remove the term “character” from the application.

- Chris Crow creates a series of drawings featuring a stylized flamingo in several poses and wearing different hats. He files an application to register his drawings under the title “Concept Drawings for Character Designs” and he asserts a claim in “two-dimensional artwork.” The registration specialist may register the claim and may send the applicant a warning letter noting that the registration covers only the specific sketches included in the deposit.

- Chloe Crown creates a series of drawings depicting several well- known comic book characters. She files an application that asserts a claim in “character redesigns” or “new versions of characters.” The registration specialist may ask Chloe if she has permission to prepare these derivative works and to clarify the derivative authorship that she contributed to the preexisting material.

- Wording.

- Mere scripting or lettering, either with or without uncopyrightable ornamentation.

- Handwritten words or signatures, regardless of how fanciful they may be.

- Mere spatial placement or format of trademark, logo, or label elements.

- Uncopyrightable use of color, frames, borders, or differently sized font.

- Mere use of different fonts or functional colors, frames, or borders, either standing alone or in combination.

- Lori Lewis submits a logo consisting of two letters linked together and facing each other in a mirror image, and two unlinked letters facing each other and positioned perpendicular to the linked letters. The registration specialist will refuse to register this work because letters alone cannot be registered, and there is insufficient creativity in the combination and arrangement of these elements. See Coach, Inc. v. Peters, 386 F. Supp.2d 495, 498 (S.D.N.Y. 2005).

- If the works are unpublished it may be possible to register them as an unpublished collection. Photographs or illustrations of the two- or three-dimensional works may be used as identifying material in this situation, provided that the applicant asserts a claim in the works depicted in those images rather than the authorship involved in creating the images themselves.

- If the works were physically bundled together for distribution to the public as a single, integrated unit and if all the works were first published in that integrated unit, it may be possible to register them using the unit of publication option.

- Reproductions of purely textual works.

- Reproductions in which the only changes are to the size or font style of the text in an underlying work.

- Mere scans or digitizations of texts or works of art.

- Reproductions in which the only change from the original work is a change in the printing or manufacturing type, paper stock, or other reproduction materials.

- Preservation and restoration efforts.

- Any exact duplication, regardless of the medium used to create the duplication (e.g., hand painting, etching, etc.).

- Gary Grant creates a pie chart that presents demographic information on five generations of a selected family. Gary files an application asserting a claim in “two-dimensional artwork, text, and chart.” The pie chart, in and of itself, is not copyrightable and cannot be registered. The registration specialist will communicate with the applicant and ask him to limit the claim to any registrable textual or compilation authorship.

- Gayle Giles creates a columnar table that records information about her son’s physical and intellectual growth in ten selected categories. Gayle includes text and photographs throughout the table. Gayle files an application asserting a claim in “design, text, photographs, and two-dimensional artwork.” The registration specialist will ask the applicant to limit the claim to the text, photographs, and the compilation of data to the extent that the selection and arrangement are original.

- Terence Town creates five drawings that show the same screw from different perspectives (e.g., top-down, bottom-up, left elevation, right elevation, and a close-up of the screw’s grooves). Terence files an application that asserts a claim in “technical drawing.” The drawings do not provide information concerning the measurements, specifications, or other information concerning the size, design, or material composition of the screw depicted therein. The registration specialist may register the claim. The registration covers the drawings, but not the screw itself.

- Teresa Todorov submits several drawings that contain specifications and information concerning the fastener depicted therein. The applicant asserts a claim in a “technical drawing and text” as well as “technical drawing and compilation.” The registration specialist may ask the applicant to limit the claim to “technical drawing,” because this term adequately describes the authorship in the drawings together with the compilation of information and data concerning the depicted object. The specialist would accept a claim in “text” only if the drawing contained adequate descriptive or informational textual matter other than mere numbers, measurements, descriptive words and phrases, or the like.

- Tina Thorn submits a set of drawings and asserts a claim in “drawings for a building.” The registration specialist will communicate with the applicant, because it is unclear whether Tina intends to register the drawings or the architectural work depicted therein.

- Archer Anthony designs a unique birdhouse and attempts to register his creation as an architectural work. The registration specialist will refuse to register the claim, because a birdhouse is not designed for human occupancy.

- Stacey Stone designs a motel comprised of a central hall with uniformly shaped rectangular rooms. The registration specialist will refuse to register this claim because it is a standard configuration of space.

- Fulton Fowler designed a house with a solar-powered hot water heater and an earthquake-resistant bracing system. He filed an application to register each element of his design. The registration specialist may register the overall design as an architectural work if it is sufficiently original, but the specialist will ask the applicant to remove the references to the heater and bracing system.

- A sufficiently creative decorative hood ornament on an automobile.

- Artwork printed on a t-shirt, beach towel, or carpet.

- Chapter 900: 41 12/22/2014 A colorful pattern decorating the surface of a shopping bag.

- A drawing on the surface of wallpaper.

- A floral relief decorating the handle of a spoon.

- Frederique Fallon creates a fabric design with swirls of color and images of people. She uses this fabric to produce a classic A-line dress. Frederique applies to register the fabric design and the dress. The registration specialist will register the fabric design because it is sufficiently creative, but will refuse to register the dress itself because it is a useful article.

- Corinne Clark creates an outfit that includes boots, pants, a belt, a shirt, a vest, an eye patch, and a plastic sword. She files an application to register the outfit as a “pirate costume.” The registration specialist will refuse registration because the clothing elements are not separable from the functional aspects of the outfit and because the sword is commonplace and unoriginal.

- Cornelius Change files an application to register a “witch costume” that consists of a white dress, pointed hat, high heeled shoes, broom, angel wings, and a skull-and-crossbones necklace. Because the wings and necklace are physically separable from the useful aspects of the costume, the registration specialist will examine these

- Dinah Dunn submits a claim to register a nose mask in the shape of a pig snout. The mask would not be considered a useful article because it does not perform a utilitarian function, and it may be eligible for registration if it is sufficiently creative. See Masquerade Novelty, Inc. v. Unique Industries, Inc., 912 F.2d 663, 671 (3d Cir. 1993).

- Brenda Bland creates a color-coded daily journal. The journal includes six columns with typical headings and multiple colors to aid the user in organizing content. The registration specialist will refuse to register this journal because it is a blank form that does not contain a sufficient amount of literary or pictorial authorship to support a registration.

- Bernice Brown creates a daily diary that includes six columns with typical headings and graphic artwork along the border of each page. The registration specialist will refuse to register the columns and headings because it is merely a blank form, but may register the decorative border if it is sufficiently creative.

- Blythe Burn files an application to register a “graphic aid for diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease.” The deposit copy consists of a blank form for recording patient data. The form contains eight boxes with various questions that are intended to identify symptoms of this disease. The registration specialist will refuse the claim in “graphic aid” and may refer the claim to the Literary Division to determine whether the textual authorship supports a claim in a literary work.

- Medical x-rays.

- Magnetic resonance imaging.

- Echocardiography.

- Echo mammography.

- Varieties of ultrasound.

- Iodinated ultra venous imaging.

- Angiography.

- Electrocardiography.

- Three-dimensional computed tomography.

- Positron emission tomography.

- Electroencephalography imaging.

- Computed axial tomography.

- Xavier Xander files an application for an x-ray of a broken arm and describes his authorship as a “photograph.” The registration specialist will refuse to register the claim.

- Xenia Xon submits an application for an x-ray of a farm animal that has been modified with bright red colors and original images of processed food products. She describes her authorship as “two- dimensional artwork.” The registration specialist may register the claim, because it includes creative elements that are conceptually separable from the x-ray.

906.2 Familiar Symbols and Designs

Familiar symbols and designs are not protected by the Copyright Act. 37 C.F.R. § 202.1(a). Likewise, the copyright law does not protect mere variations on a familiar symbol or design, either in two or three-dimensional form. For representative examples of symbols or designs that cannot be registered with the U.S. Copyright Office, see Chapter 300, Section 313.4(J).

A work that includes familiar symbols or designs may be registered if the registration specialist determines that the author used these elements in a creative manner and that the work as a whole is eligible for copyright protection.

Examples:

906.3 Colors, Coloring, and Coloration

Mere coloration or mere variations in coloring alone are not eligible for copyright protection. 37 C.F.R. § 202.1(a).

Merely adding or changing one or relatively few colors in a work, or combining expected or familiar pairs or sets of colors is not copyrightable, regardless of whether the changes are made by hand, computer, or some other process. This is the case even if the coloration makes a work more aesthetically pleasing or commercially valuable. For example, the Office will not register a visual art work if the author merely added relatively few colors to a preexisting design or simply created multiple colorized versions of the same basic design. Copyright Registration for Colorized Versions of Black and White Motion Pictures, 52 Fed. Reg. 23,443, 23,444 (June 22, 1987). Likewise, the Office generally will not register a visual art work if the author merely applied colors to aid in the visual display of a graph, chart, table, device, or other article.

The Office understands that color is a major element of design in visual art works, and the Office will allow an applicant to include appropriate references to color in an application. For instance, if an applicant refers to specific colors or uses terms such as “color,” “colored,” “colors,” “coloring,” or “coloration,” the registration specialist Chapter 900: 12 12/22/2014 generally will not reject the claim if the work contains a sufficient amount of creative authorship aside from the coloration alone.

Examples:

will refuse to register the blue variation because it is identical to the preexisting “Baby Girl Fabric” design aside from the mere change in background color.

906.4 Typeface, Typefont, Lettering, Calligraphy, and Typographic Ornamentation

As a general rule, typeface, typefont, lettering, calligraphy, and typographic ornamentation are not registrable. 37 C.F.R. § 202.1(a), (e). These elements are mere variations of uncopyrightable letters or words, which in turn are the building blocks of expression. See id. The Office typically refuses claims based on individual alphabetic or numbering characters, sets or fonts of related characters, fanciful lettering and calligraphy, or other forms of typeface. This is true regardless of how novel and creative the shape and form of the typeface characters may be. A typeface character cannot be analogized to a work of art, because the creative aspects of the character (if any) cannot be separated from the utilitarian nature of that character.

Examples:

There are some very limited cases where the Office may register some types of typeface, typefont, lettering, or calligraphy, such as the following:

glass, spooky-fog, and weathered-and-worn), while potentially separable, is de minimis and not sufficient to support a registration.

The Office may register a computer program that creates or uses certain typeface or typefont designs, but the registration covers only the source code that generates these designs, not the typeface, typefont, lettering, or calligraphy itself. For a general discussion of computer programs that generate typeface designs, see Chapter 700, Section 723.

To register the copyrightable ornamentation in typeface, typefont, lettering, or calligraphy, the applicant should describe the surface decoration or other ornamentation and should explain how it is separable from the typeface characters. The applicant should avoid using unclear terms, such as “typeface,” “type,” “font,” “letters,” “lettering,” or similar terms.

906.5 Spatial Format and Layout Design

As a general rule, the U.S. Copyright Office will not accept vague claims in “format” or “layout.” The general layout or format of a book, a page, a website, a webpage, a poster, a form, etc., is not copyrightable, because it is merely a template for expression and does not constitute original expression in and of itself. If the applicant uses the terms “layout” and/or “format” in the application, the registration specialist will communicate with the applicant to clarify the claim. Copyright protection may be available for the author’s original selection and/or arrangement of specific content if it is sufficiently creative, but the copyright does not extend to the organization without that particular content.

Examples:

906.6 Mechanical Processes and Random Selection

The copyright law only protects works of authorship that are created by human beings. Works made through purely mechanical processes or with an automated selection and arrangement are not eligible for copyright protection. The U.S. Copyright Office will Chapter 900: 15 12/22/2014 refuse to register a claim in a work that is created through the operation of a machine or process without any human interaction, even if the design is randomly generated.

Example:

906.7 Naturally Occurring and Discovered Material

Because human authorship is required for copyright protection, the U.S. Copyright Office will not register naturally occurring objects or materials that are discovered in nature. This includes natural objects or materials with standard wear or acute breaks or fissures resulting from weather conditions or other natural phenomena, such as water currents, wind, rain, lightning, sunlight, heat, or cold. Similarly, the Office will refuse to register a work that is created through naturally occurring processes or events, such as the resulting visual appearance of an object or liquid when different chemical elements interact with each other.

Examples:

906.8 Functional and Useful Elements

The copyright law does not protect useful articles, utilitarian designs, or any functional portion of a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work. However, the decorative ornamentation on a useful article may be registrable if it is separable from the functional aspects of that article. For example, a lamp is a considered a useful article, because it has an intrinsic utilitarian function, namely, to provide lighting. By contrast, a three-dimensional floral design affixed to the base of a lamp or a two-dimensional garden design painted on a lamp shade does not have a useful purpose. The U.S. Copyright Office may register those design elements if they are separable from the functional aspects of the lamp and if they are sufficiently original and creative. Fabrica, Inc. v. El Dorado Corp., 697 F.2d 890, 893 (9th Cir. 1983) (“if an article has any intrinsic utilitarian function, it can be denied copyright protection except to the extent that its artistic features can be identified separately and are capable of existing independently as a work of art”).

For a general discussion of the legal standard for evaluating useful articles, see Section 924.

907 Derivative Visual Art Works

907.1 Copyrightable Authorship in Derivative Works

A derivative visual art work is a work based on or derived from one or more preexisting works. A derivative work may be registered if the author of that work contributed a sufficient amount of new authorship to create an original work of authorship. The new material must be original and copyrightable in itself.

Examples of visual art works that may be registered as derivative works include:

Examples of works that cannot be registered as derivative works, because they contain no new authorship or only a de minimis amount of authorship include the following types of visual art works:

For a general discussion of the legal standard for determining whether a derivative work contains a sufficient amount of original expression to warrant registration, see Chapter 300, Section 311.

Chapter 900: 17 12/22/2014907.2 Permission to Use Preexisting Material

Authors often incorporate material created by third parties into their visual art works, such as a third party photograph that is used in a collage or third party clip art that is used in a logo. Generally, if the third party material is protected by copyright, the applicant must exclude that material from the claim using the procedure described in Chapter 600, Section 621.8. However, the applicant does not have to disclaim uncopyrightable elements, such as letters of the alphabet or geometric shapes.

The U.S. Copyright Office generally does not investigate the copyright status of preexisting material or investigate whether it has been used lawfully. However, the registration specialist may communicate with the applicant to determine whether permission was obtained where a recognizable preexisting work has been incorporated into a visual art work. The applicant may clarify the lawful use of preexisting material by including a statement to that effect in the Note to Copyright Office field of the online application or in a cover letter submitted with the paper application. If it becomes clear that preexisting material was used unlawfully, the registration specialist will refuse to register the claim.

Example:

For more information on derivative works incorporating third party content, see Chapter 300, Section 313.6(B).

908 Jewelry

Jewelry designs are typically protected under the U.S. copyright law as sculptural works, although in rare cases they may be protected as pictorial works. This Section discusses certain issues that commonly arise in connection with such works.

908.1 What Is Jewelry?

For purposes of copyright registration, jewelry includes any decorative article that is intended to be worn as a personal adornment, regardless of whether it is hung, pinned, or clipped onto the body (such as necklaces, bangles, or earrings) or pinned, clipped, or sewn onto clothing (such as brooches, pins, or beaded motifs).

Jewelry also includes jeweled and beaded designs that are applied to garments and accessories (such as hatpins, hairpins, hair combs, and tiepins). However, when these types of works are fixed onto clothing and/or accessories, they may be registered only if Chapter 900: 18 12/22/2014 they are physically or conceptually separable from the clothing and/or accessories. For a discussion of this issue, see Section 924.3(A).

908.2 Copyrightable Authorship in Jewelry

Jewelry designs may be created in a variety of ways, such as carving, cutting, molding, casting, or shaping the work, arranging the elements into an original combination, or decorating the work with pictorial matter, such as a drawing or etching.

The U.S. Copyright Office may register jewelry designs if they are sufficiently creative or expressive. The Office will not register pieces that, as a whole, do not satisfy this requirement, such as mere variations on a common or standardized design or familiar symbol, designs made up of only commonplace design elements arranged in a common or obvious manner, or any of the mechanical or utilitarian aspects of the jewelry. Common de minimis designs include solitaire rings, simple diamond stud earrings, plain bangle bracelets, simple hoop earrings, among other commonly used designs, settings, and gemstone cuts.

Examples:

908.3 Application Tips for Jewelry

When preparing the identifying material for a jewelry design (which may consist of photographs or drawings) the applicant should include all of the copyrightable elements that the applicant intends to register. This is important because the registration specialist can examine only the designs that are actually depicted in the identifying material. If the applicant wants the registration to cover more than just the face of a jewelry design, the identifying material should depict the design from different angles. Additionally, if the applicant wants the registration to cover part of the design or details that are relatively small, the applicant should make sure that those portions are clearly visible in the identifying material.

When evaluating a jewelry design for copyrightable authorship, the registration specialist will consider the design as a whole, rather than the component elements of the design. In making this determination, the specialist may consider the following aspects of a jewelry design:

The following aspects of jewelry generally are not copyrightable and are not considered in analyzing copyrightability:

As a general rule, if the shape or decoration of a particular element contains enough authorship to support a registration, the specialist will register the claim. If not, the specialist will consider other factors, such as the selection, coordination, and/or arrangement of elements, as well as the degree of symmetry.

When evaluating the copyrightability of a jewelry design, the specialist may consider the number of elements in the design. More elements may weigh in favor of copyrightability, although a work containing multiple elements may be uncopyrightable if the elements are repeated in a standard geometric arrangement or a commonplace design. A work containing only a few elements may be copyrightable if the decoration, arrangement, use of color, shapes, or textures are sufficient to support a claim.

909 Photographic Works

The U.S. copyright law protects photographs as pictorial works. This Section discusses certain issues that commonly arise in connection with such works.

909.1 Copyrightable Authorship in Photographs

As with all copyrighted works, a photograph must have a sufficient amount of creative expression to be eligible for registration. The creativity in a photograph may include the photographer’s artistic choices in creating the image, such as the selection of the subject matter, the lighting, any positioning of subjects, the selection of camera lens, the placement of the camera, the angle of the image, and the timing of the picture.

Example:

the claims, because each photographer selected the angle and positioning of his or her photograph, among other creative choices.

909.2 Subject Matter of Photographs

To be eligible for copyright protection, the subject of the photograph does not need to be copyrightable. A photograph may be protected by copyright and registered with the U.S. Copyright Office, even if the subject of the photograph is an item or scene that is uncopyrightable or in the public domain.

Example:

909.3 Photographic Reproductions, Digital Copying, and Editing

Although most photographs warrant copyright protection, the U.S. Copyright Office will not register photographs that do not display a sufficient amount of creative expression. A photograph that is merely a “slavish copy” of a painting, drawing, or other public domain or copyrighted work is not eligible for registration. The registration specialist will refuse a claim if it is clear that the photographer merely used the camera to copy the source work without adding any creative expression to the photo. Similarly, merely scanning and digitizing existing works does not contain a sufficient amount of creativity to warrant copyright protection.

Example:

The Office often receives applications to register preexisting works that have been restored to their original quality and character. Merely restoring a damaged or aged photograph to its original state without adding a sufficient amount of original, creative authorship does not warrant copyright protection.

The registration specialist will analyze on a case-by-case basis all claims in which the author used digital editing software to produce a derivative photograph or artwork. Typical technical alterations that do not warrant registration include aligning pages and columns; repairing faded print and visual content; and sharpening and balancing colors, tint, tone, and the like, even though the alterations may be highly skilled and may produce a valuable product. If an applicant asserts a claim in a restoration of or touchups to a preexisting work, the registration specialist generally will ask the Chapter 900: 21 12/22/2014 applicant for details concerning the nature of changes that have been made. The specialist will refuse all claims where the author merely restored the source work to its original or previous content or quality without adding substantial new authorship that was not present in the original.

The specialist may register a claim in a restored or retouched photograph if the author added a substantial amount of new content, such as recreating missing parts of the photograph or using airbrushing techniques to change the image. As a general rule, applicants should use terms such as “photograph” or “2-D artwork” to describe this type of authorship, and should avoid using terms such as “digital editing,” “touchup,” “scanned,” “digitized,” or “restored.”

Examples:

910 Games

Games often include both copyrightable and uncopyrightable elements. The copyrightable elements of a game may include text, artwork, sound recordings, and/or audiovisual material. These elements may be protectable if they contain a sufficient amount of original authorship. Uncopyrightable elements include the underlying ideas for a game and the methods for playing and scoring a game. These elements cannot be registered, regardless of how unique, clever, or fun they may be.

When completing an application for this type of work, applicants should describe the specific elements of the game that the applicant intends to register, such as the text, the artwork on a playing board, and/or the original sculptural elements of game pieces. Applicants should not assert a claim in “game” or “game design,” because it is generally Chapter 900: 22 12/22/2014 understood that the game as a whole encompasses the ideas underlying the game. For the same reason, applicants should not assert a claim in the methods for playing the game.

Examples:

For information on how to register purely literary aspects of a game, see Chapter 700, Section 714. For information concerning the deposit requirements for games, see Chapter 1500, Sections 1509.1(B) and 1509.3(A)(7).

911 Characters

The original, visual aspects of a character may be protected by copyright if they are sufficiently original. This may include the physical attributes of the character, such as facial features and specific body shape, as well as images of clothing and any other visual elements.

The U.S. Copyright Office will register visual art works that depict a character, such as drawings, sculptures, and paintings. A registration for such works extends to the particular authorship depicted in the deposit material, but does not extend to unfixed characteristics of the character that are not depicted in the deposit. Nor does it cover the name or the general idea for the character.

When completing an application to register such works, the applicant should use an appropriate term to describe the authorship embodied in the deposit material, such as “2-D artwork,” “photograph,” or “text.” Applicants should not refer to or assert claims in

Chapter 900: 23 12/22/2014“character,” “character concept, idea, or style,” or a character’s generalized personality, conduct, temperament, or costume. If the applicant uses these terms, the registration specialist may ask the applicant to remove them from the claim. Likewise, if the deposit material contains a well-known or recognizable character, the specialist may ask the applicant to exclude that preexisting material from the claim if the applicant fails to complete the Limitation of Claim portion of the application.

Examples:

912 Cartoons, Comic Strips, and Comic Books

Cartoons, comic strips, and comic books typically contain pictorial expression or a combination of pictorial and written expression. These types of works may be registered as visual art works or literary works, depending on the nature of the expression that the author contributed to the work. If the work contains pictorial material or a substantial amount of pictorial material combined with text, the applicant should select Work of the Visual Arts (in the case of an online application) or Form VA (in the case of a paper application). If the work mostly contains text with a small amount of pictorial material, the applicant should select Literary Work for an online application or Form TX for a paper application. If the types of authorship are roughly equal, the applicant may use any type of application that is appropriate.

A registration for a cartoon, comic strip, or comic book only covers the specific work that is submitted to the U.S. Copyright Office. The Office does not offer so-called “blanket registrations” that cover prior or subsequent iterations of the same work. For example, a registration for a comic strip that depicts a particular character covers the expression set forth in that particular strip, but it does not cover the character per se or any other Chapter 900: 24 12/22/2014 strip or other work that features the same character. (For more information concerning characters, see Section 911.)

In some cases it may be possible to register a number of cartoons, comic strips, or comic books with one application and one filing fee. If all the works are unpublished it may be possible to register them as an unpublished collection. If all the works were physically bundled together by the claimant for distribution to the public as a single, integrated unit, and if all the works were first published in that integrated unit it may be possible to register them using the unit of publication option. However, the works cannot be aggregated simply for the purpose of registration; instead they must have been first distributed to the public in the packaged unit. If all of the works were first published as a contribution to a periodical, such as a newspaper or magazine, it may be possible to register the contributions as a group. For detailed information concerning unpublished collections, the unit of publication option, and the group registration option for contributions to periodicals, see Chapter 1100, Sections 1106, 1107, and 1115.

Comic books are typically created by multiple authors, and the issues surrounding the authorship and ownership of the various contributions can be complex. In some cases, the creators may prepare their contributions on a work for hire basis as employees or pursuant to a freelancer work made for hire agreement. In some cases, the comic book may be a joint work. In other cases, different authors may create different aspects of the comic book, with some aspects originating from the publisher and other aspects originating from one or more individual, nonemployee authors (i.e., derivative works). For example, the publisher may claim ownership of the characters and the basic story, and may hire others to create the artwork, text, and/or lettering for particular issues. Then a freelance or staff contributor may contribute coloring and editing. If all of the work is done on a work made for hire basis, the authorship is clearly owned by the publisher, and as such the publisher should be named as the claimant.

If multiple authors contributed to the comic book as individual authors (not as joint authors or under a work made for hire agreement), and if it is unclear from the face of the deposit copy(ies) which author created what authorship and on what basis, the applicant should provide that information in the Author Created field of the online application or the Nature of Authorship space of the paper application. Such claims may require multiple separate applications to register the derivative authorship (e.g., an application for the pencil drawings and a separate application for the coloring of the preexisting drawings).

In some cases, comic book publishers license the use of another party’s characters and stories. In other cases, the publisher creates the stories, but the characters have been licensed. In such cases, the applicant should exclude the licensed characters and/or stories from the claim by stating “licensed character” or “licensed character and storyline” in the Material Excluded / Preexisting Materials field/space. The claimant should not name the licensor of the preexisting characters and/or stories as an author of the new text and artwork in the comic book.

The registration specialist will communicate with the applicant if the authorship or ownership information provided in the application is unclear or inconsistent with other statements in the application, the deposit copy(ies), or industry practice. In addition, the Chapter 900: 25 12/22/2014 specialist may question whether a given work is a collective work or joint work, rather than a work consisting of separately owned contributions or works.

The Office will not register mere reprints, reissues, re-inks/letters/colors, or previously published, or previously registered comic books, unless the author contributed new copyrightable authorship in adapting or changing the preexisting content.

913 Trademarks, Logos, and Labels

913.1 Copyrightable Authorship in Trademarks, Logos, and Labels

A visual art work that is used as a trademark, logo, or label may be registered if it satisfies “the requisite qualifications for copyright.” 37 C.F.R. § 202.10(b). The authorship in the work may be pictorial, graphic, or in rare cases sculptural, or the work may contain a combination of these elements. When reviewing an application to register a trademark, logo, or label the U.S. Copyright Office will examine the work to determine if it embodies “some creative authorship in its delineation or form.” Id. § 202.10(a). However, the Office will not consider whether the work has been or can be registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. Id. § 202.10(b).

The copyright law covers the creative aspects of a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work, regardless of whether the work has been used or is capable of being used as an indicator of source. Unlike trademark law, copyright law is not concerned with consumer confusion and a trademark, logo, or label may be eligible for copyright protection regardless of whether the work is distinctive or whether consumers may be confused by the use of that work. In other words, a visual art work may be distinctive in the trademark sense, even if it does not qualify as a work of original authorship in the copyright sense.

The Office typically refuses to register trademarks, logos, or labels that consist of only the following content:

Example:

913.2 Application Tips for Trademarks, Logos, and Labels

When completing an application for a trademark, logo, or label, applicants should describe the pictorial, graphic, or sculptural authorship that the author contributed to the work. Applicants should avoid using vague terms, such as “trademark design,” “trade dress design,” “mark,” “logo,” “logotype,” or “symbol.” Likewise, applicants should avoid using the following terms which may be questioned by the registration specialist: “composite work,” “collective work,” “selection and arrangement,” “look and feel,” “distinctive,” “distinctiveness,” “totality of design,” or “total concept and feel.”

914 Catalogs

For purposes of copyright registration, catalogs are considered compilations of information or collective works that contain written descriptions and/or pictorial depictions of two or three-dimensional products. Catalogs generally contain copyrightable pictorial and/or literary authorship, and they also may contain copyrightable authorship in the selection, coordination, and/or arrangement of copyrightable or uncopyrightable elements.

The photographs within a catalog may be registered together with the catalog as a whole (i) if the photographs and the catalog were created by the same author, or (ii) if the copyright claimant owns all of the rights in the photographic authorship and compilation authorship that the author contributed to the catalog. However, a claim in the photographs does not extend to the actual works or objects depicted in those images.

A catalog may be registered as a compilation of photographs or a collective work consisting of photographs if there is a sufficient amount of creative expression in the author’s selection, coordination, and/or arrangement of the images. However, a catalog is not considered a compilation of the works or objects depicted in those photographs, nor is it considered a collective work consisting of the works or objects depicted therein. Accord Registration of Claims to Copyright, 77 Fed. Reg. 37,605, 37,606 (June 22, 2012). As a result, a registration for a catalog generally does not extend to the works or objects shown in that work, even if they are eligible for copyright protection and even if the claimant owns all of the rights in those works or objects. Instead, the registration extends only to the pictorial authorship involved in creating the images, and the authorship involved in selecting, coordinating, and/or arranging those images within the catalog as a whole.

Chapter 900: 27 12/22/2014By contrast, if the applicant submits photographs or pictorial illustrations of a two- or three-dimensional work (as opposed to a catalog depicting a two- or three-dimensional work), the registration may cover the pictorial or sculptural authorship that the author contributed to that work if it is clear that the photographs or illustrations are being used as identifying material for the work depicted therein and that the applicant is not attempting to register the authorship involved in creating those images.

As a general rule, it is not possible to register a group of pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works with one application, one filing fee, and a submission of identifying material. Instead, the applicant generally must submit a separate claim for each work. However, there are two limited exceptions to this rule.

When a group of photographs are published in a catalog the works depicted therein are considered published, regardless of whether they are two- or three-dimensional. However, the fact that a group of works were published in the same catalog does not necessarily mean that the catalog constitutes a unit of publication or that the works may be registered together with the unit of publication option.

A unit of publication is a package of separately fixed elements and works that are physically bundled together by the claimant for distribution to the public as a single, integrated unit. The unit must contain an actual copy of the works and the works must be distributed to the public as an integral part of the unit. A unit that merely contains a representation of the works, or merely offers those works to the public (without actually distributing them) does not satisfy this requirement. For example, a boxed set of fifty different greeting cards sold as a package to retail purchasers would qualify as a unit of publication. By contrast, a catalog offering fifty different greeting cards for individual purchase would not be considered a unit of publication, even if all of the cards may be ordered from the catalog for a single price. Although a catalog may offer multiple items for sale to the public, the catalog itself does not qualify as a unit of publication, because the items themselves are not packaged together in the catalog for actual distribution to the public.

For a general discussion of compilations and collective works, see Chapter 500, Sections 508 and 509. For detailed information concerning unpublished collections and the unit of publication option, see Chapter 1100, Sections 1106 and 1107.

Chapter 900: 28 12/22/2014915 Retrospective Books and Exhibition Catalogs

Retrospective books are published books that review or look back on the career of a visual artist. They typically contain both new and preexisting authorship.

The new authorship is usually prepared expressly for the retrospective book and may include elements such as an introduction, critical essays, photographs, annotated bibliographies, chronological timelines, and the like.

As for the visual artist’s works, retrospective books usually contain (i) works that were published before they appeared in the new book, and (ii) other works that have never been sold or otherwise published or publicly exhibited before they appeared in the new book.

When a previously unpublished work is first published in a retrospective book or exhibition catalog, the fact that the work has been published will affect the subsequent registration options for that work. For this reason, artists may want to consider registering their pictorial, graphic, or sculptural works prior to authorizing their depiction in a retrospective book or exhibition catalog.

To register a retrospective book, the applicant should limit the claim to the new content that was prepared specifically for the book, such as new artwork, essays, photographs, indexes, chronologies, bibliographies, or the like. Any artwork that was previously registered, published, or in the public domain should be excluded from the claim using the procedures described in Chapter 600, Section 621.8.

In all cases, the applicant should anticipate that the registration specialist will raise questions about the ownership and first publication provenance of artwork depicted in a retrospective book. Therefore, when completing the application, the applicant should provide as much information about those works as possible.

916 Art Prints and Reproductions

916.1 Copyrightable Authorship in Art Prints and Reproductions

A reproduction of a work of art or a two-dimensional art print may be protected as a derivative work, but only if the print or reproduction contains new authorship that does not appear in the original source work. This category includes hand painted reproductions (typically on canvas); plate, screen, and offset lithographic reproductions of paintings; Giclée prints; block prints; aquaprint; artagraph; among other forms of expression.

Making an exact copy of a source work is not eligible for copyright protection, because it is akin to a purely mechanical copy and includes no new authorship, regardless of the process used to create the copy or the skill, craft, or investment needed to render the copies. For the same reason, a print or reproduction cannot be protected based solely on the complex nature of the source work, the apparent number of technical decisions needed to produce a near-exact reproduction, or the fact that the source work has been rendered in a different medium. For example, the U.S. Copyright Office will not register the following types of prints and reproductions:

Chapter 900: 29 12/22/2014The Office will register any new and creative authorship that is fixed in a print or reproduction. However, the registration specialist will not assume that all such works embody new, registrable authorship. In addition, the specialist will communicate with the applicant if the application refers to a new process previously unknown to the Office, or if it appears that the author made no more than a high quality copy of the source work.

916.2 Application Tips for Art Prints and Reproductions

916.2(A) Distinguishing Art Prints and Reproductions from the Source Work and Identifying Material

To register an art print or a reproduction of a work of art, the applicant should fully describe the new authorship that the author contributed to the source work. As a general rule, the terms “2-D artwork” or “reproduction of work of art” may be used to describe the authorship involved in recasting, transforming, or adapting the source work. When completing an online application the applicant should provide this information in the Author Created field. When completing a paper application, the applicant should provide this information in the Nature of Authorship space. In addition, applicants are strongly encouraged to provide a clear description of the new authorship that the author contributed to the art print or reproduction using specific terms that distinguish the new authorship from the source work. This information may be provided in the Note to Copyright Office field or in a cover letter. Doing so may avoid the need for correspondence that could delay the examination of the application.

The applicant should not refer to the authorship in the source work that has been recast, transformed, or adapted by the author of the print or reproduction. Likewise, the applicant should not refer to the type of identifying material that the applicant intends to submit to the Office. For example, if the applicant intends to register a lithographic reproduction of a preexisting painting, the applicant should clearly describe the new artwork that the author contributed to that reproduction. The author should not refer to the preexisting painting that is depicted in the lithograph. If the applicant intends to submit a photograph of the lithograph as the identifying material for the claim, the applicant should not refer to the reproduction as a “photograph.” If the applicant states

Chapter 900: 30 12/22/2014“photograph” the registration specialist may assume that the applicant intends to register the authorship involved in taking the photograph of the lithograph, rather than the authorship involved in creating the reproduction of the preexisting painting.

916.2(B) Authorship Unclear

Applicants should not use vague terms to describe the new authorship that the author contributed to an art print or reproduction. Likewise, applicants should not use terms that merely describe the tools or methods that the author used to create the work, such as “computer print,” “computer reproduction,” “block print,” “offset print,” “print,” or “photoengraving,” because this suggests that the applicant may be asserting a claim in an idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery.

If the author merely painted over areas of the source work, the registration specialist may communicate with the applicant if it appears that the applicant is attempting to register the authorship (if any) involved in restoring the source work to its original condition.

917 Installation Art

The U.S. Copyright Office generally discourages applicants from using the term “installation art” in applications to register visual art works. Applicants use this term for a wide variety of artistic endeavors and it has many broad, ambiguous meanings. Because this term is unclear, the registration specialist will communicate with applicants if they describe a pictorial, graphic, or sculptural work as “installation art.”

Instead, applicants should identify any copyrightable content in the work and should describe that content using terms such as “sculpture,” “painting,” “photographs,” or the like. This is true even if the overall installation itself is a registrable work of authorship. In such cases the applicant should use accepted terms to describe the work, such as “a series of sequentially and thematically related photographs interspersed with drawn and painted images to create a larger work of authorship.”

918 Maps

Maps may be protected under the copyright law as pictorial works or sculptural works, depending on whether the work contains two- or three-dimensional authorship. Indeed, maps were among the first works that were eligible for copyright protection under the 1790 Act. This Section discusses certain issues that commonly arise in connection with such works.

918.1 Copyrightable Authorship in Maps

Maps are cartographic or visual representations of an area. Examples include terrestrial maps and atlases, marine charts, celestial maps, as well as three-dimensional works, such as globes and relief models. A map may represent a real or imagined place, such as a map in a book or videogame that depicts a fictional country.

Chapter 900: 31 12/22/2014The U.S. Copyright Office will register maps, globes, and other cartographic works if they display a sufficient amount of original pictorial or sculptural authorship.

The Office may register an original selection, coordination, and/or arrangement of cartographic features, such as roads, lakes, or rivers, cities, or political or geographic boundaries. But to be copyrightable, the work as a whole must be creative and it must not be intrinsically utilitarian. In making this determination, the Office will not consider the amount of effort required to create the work, such as surveying or cartographic field work.

918.2 Derivative Maps

Maps are often based on one or more preexisting works. A derivative map may be eligible for registration if the author added a sufficient amount of new authorship to the preexisting material, such as depictions of new roads, historical landmarks, or zoning boundaries.

If the map contains an appreciable amount of material that has been previously published, previously registered, material that is in the public domain, or material that is owned by a third party, the applicant should exclude that material from the claim and should limit the claim to the new copyrightable authorship that the author contributed to the derivative map. For guidance in completing this portion of the application, see Chapter 600, Section 621.8.