CHEESMAN et al. v. HART et al.

Circuit Court, D. Colorado.

April 28, 1890.

1. MINES AND MINING—STATUTORY CONSTRUCTION—SIDE LINES.

Where the strike of the vein passes perpendicularly through the end lines of the location, the fact that between the end lines the outcrop is forced by the surface influences of slides and débris to meander so as to make slight variations from the general trend of the strike, does not prevent the side lines from being parallel with the vein; it being only necessary in such case that they should be substantially parallel.

2. SAME—END LINES.

The fact that a location is cut by another valid claim crossing it obliquely does not make the line of such intersection the end line of the location when the location extends beyond the intersecting claim.

3. SAME.

Where part of the end of a location is adjudged to be in conflict with a prior claim, and thereupon the owners of the prior claim quitclaim the land in conflict to the owners of said location, whose possession there of is not interrupted, the location will continue to include the land in conflict.

4. SAME—LOCATION—PRESUMPTION.

Where mining location which have passed out of the hands of the original owner have Stood unchallenged for years, and have been developed to a considerable extent, it is proper in a suit involving their validity to instruct the jury that “the certificates of location are presumptive evidence of discovery, and every reasonable presumption should be indulged in by the jury in favor of the integrity of the locations.”

5. SAME—ADJOINING OWNERS—DIP.

Under Rev. St. U. S. § 2322, which gives the locators of lode claims the right to follow the dip of the vein beyond their side lines, such right is not cut off by the issue of a patent for the land into which such vein in its dip extends.

6. TRIAL—PRODUCTION OF PAPERS.

Where during the progress of a trial defendant's counsel, on being asked by plaintiff to produce a certain paper, promises to look for it, and bring it into court if found, and the plaintiff's counsel does not again call the matter to the attention of the court, the right to insist on the production of the paper, or introduce secondary evidence of its contents, is waived.

7. SAME—RIGHT TO OPEN AND CLOSE.

In an action of trespass for taking ore from plaintiff's mining claim, where the defendant admits the taking and seeks to justify it, and the only evidence necessary to make out a prima facie case for plaintiff is the production of his patent, and proof of the quantity and value of the ore taken, it is proper to allow the defendant to open and close the argument to the jury; the burden of proof on the main issue in the case being on him.

8. NEW TRIAL—JURISDICTION OF DISTRICT JUDGE.

A district judge who has, under order of the circuit judge, tried a case in another district, has jurisdiction to pass upon a motion for a new trial in the case, even after he has returned to his own district, where the parties waive his returning to the other district for the purpose of deciding the motion.

At Law. On motion for new trial.

C. J. Hughes, for plaintiffs.

B. F. Montgomery, A. S. Frost, and C. C. Parsons, for defendants.

PHILIPS, J. I have examined the grounds for new trial herein as fully as my limited time would permit, and can give but a cursory review of the many questions involved. During the progress of the trial, extending over a period of two weeks, with access to the statutes and decisions of the courts in similar mining controversies, aided by the daily discussions 99of able counsel on both sides, the court learned all it could and its conclusions on the law are expressed, as fully as seemed justifiable, in the charge to the jury reported in 40 Fed. Rep. 787. Such questions were new to the court, but it labored to understand so much of the facts and the law as would enable it to present the case fairly to the jury. Some of these questions were embarrassing, and are by no means free from doubt. The evidence impressed my mind, by a great preponderance, as tending to establish the existence of an outcrop of a lode of mineral within the surface lines of the Champion claim, and that this vein was in contemplation of the statute, a continuous one to the point of the alleged trespass.

The question of fact and law which has most perplexed the mind of the court is as to the parallelism of the defendants' claims. The parallelism of the end lines of the surveys and the parallelism of the side lines to the actual strike of the outcrop were left by the evidence in such condition as to render the determination of this fact peculiarly a matter for the jury; and I tried to so frame the charge as to leave them uninfluenced by any impressions of the court respecting the question of fact.

As to the point so much pressed by plaintiffs' counsel, that the outcrop of the vein ran so zigzag or serpentine as to make it the duty of the court to tell the jury that, as matter of law, it was not parallel to the side lines of defendants' claim, my impression at the trial was, and on further consideration my opinion is, that it was not in the mind of congress, in framing the section of the statute in question, that, where the strike of the vein passes perpendicularly through the end lines, the mere meanderings of the outcrop between the end lines (caused by the surface influences of slides and debris on the mountain sides, as the evidence impressed me was the fact in this case) should absolutely control the question of parallelism; but rather that the spirit and reason of the statute require that the settled and permanent course of the vein on its strike, as nature fixed it, should control; of course such zigzagging being restricted to slight variations from the general direction and trend of the strike. The illustration furnished by the expert witness Boehmer in the scored-out apple quite aptly demonstrated the principle of law and fact. It was with this thought in mind that I employed in the charge the term, “substantially parallel,” assigned for error in the motion for new trial. It ought not to be that the court should apply to these locations the most exact mathematical precision. The law, being designed for the encouragement and benefit of miners, should be liberally construed, and should look to substance rather than shadow; and here, as elsewhere, should be administered on lines of obvious common sense. So long as the right of trial by jury stands, the court should be allowed to assume that the jury may understand the purport of words and terms which by their common use have acquired a recognized meaning. The term “substantially” means “really, truly, essentially, competently.” In the connection in which it was used in the charge the jury could but understand that the variation from parallelism must be substantial, material, and 100real; that a very slight variation from a mathematical line was not of substance. I am free to make this confession, that neither at the trial nor after reference to my minutes did or do I obtain from the evidence a very satisfactory impression either as to the precise shape in which the original survey of the Champion claim, or the relocation of 1882, left it. There was an amended location in 1886. Whether or not the lines were substantially parallel under all the evidence, (much of it conflicting,) together with the aid of the maps and diagrams before them, I thought was peculiarly a question for the jury. Following the decisions of the supreme court of Colorado, the charge told the jury that “such amendments or relocations, when made, had relation back to the time of the original location; and these plaintiffs are in no position in this controversy to question such amendments or relocations.” The plaintiffs had the full benefit of what counsel so urgently contends for respecting the end lines intersecting the actual outcrop in the following declaration of law, drawn by himself:

“The court further charges the jury, at the instance of the plaintiffs, that end lines, as designated in the location certificate, are not necessarily in law the end lines, unless they actually cross the actual outcrop of the vein.”

This is certainly as much as, if not more than, they could claim, in view of the language of the federal statute, (section 2322:)

“Their right of possession to such outside parts of such veins or ledges shall be confined to such portions there of as lie between vertical planes, drawn downward * * * through the end lines of their locations.”

In addition to which the jury were further charged that—

“The statute of the United States also requires that the end lines of the claim should be parallel with each other, and, in asserting a right to follow the vein on its dip without the side lines of their location into plaintiffs' location, defendants must show the outcrop or apex of such vein to be in their own location throughout the ground in controversy, being the extent of the locations of plaintiffs and defendants, parallel to each other.”

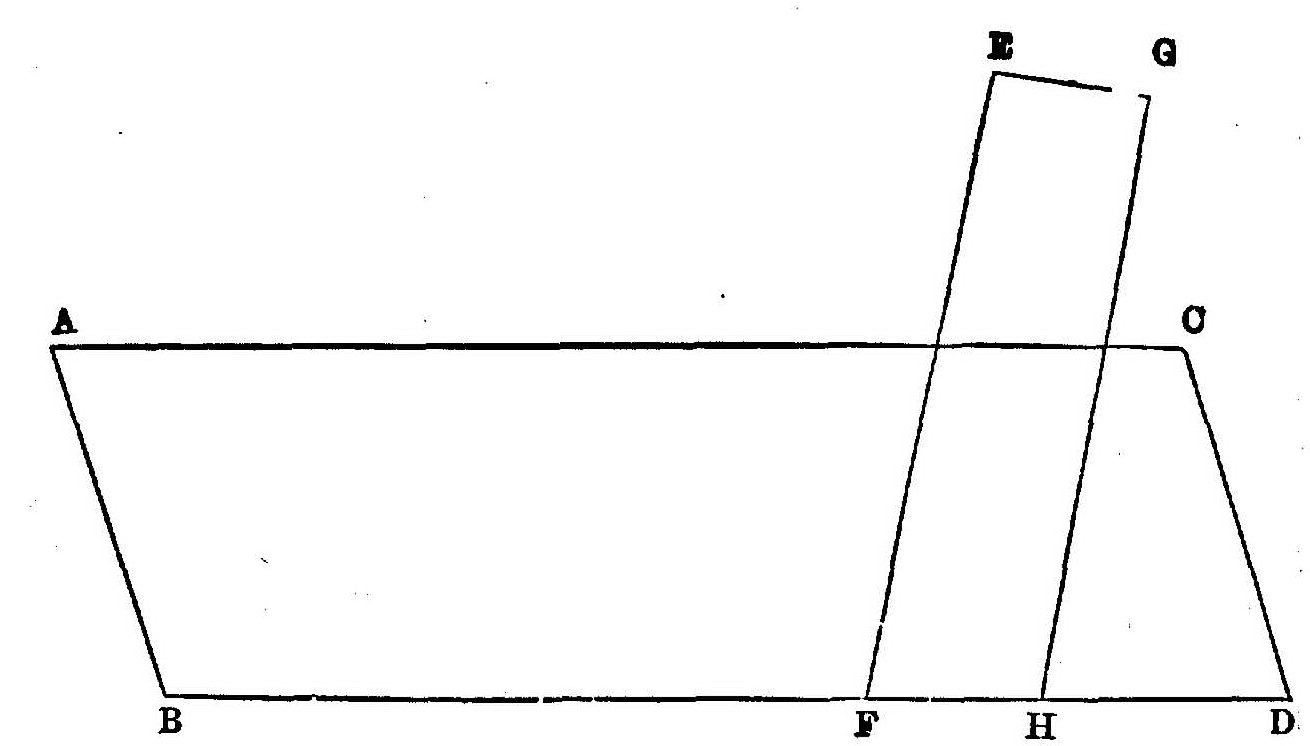

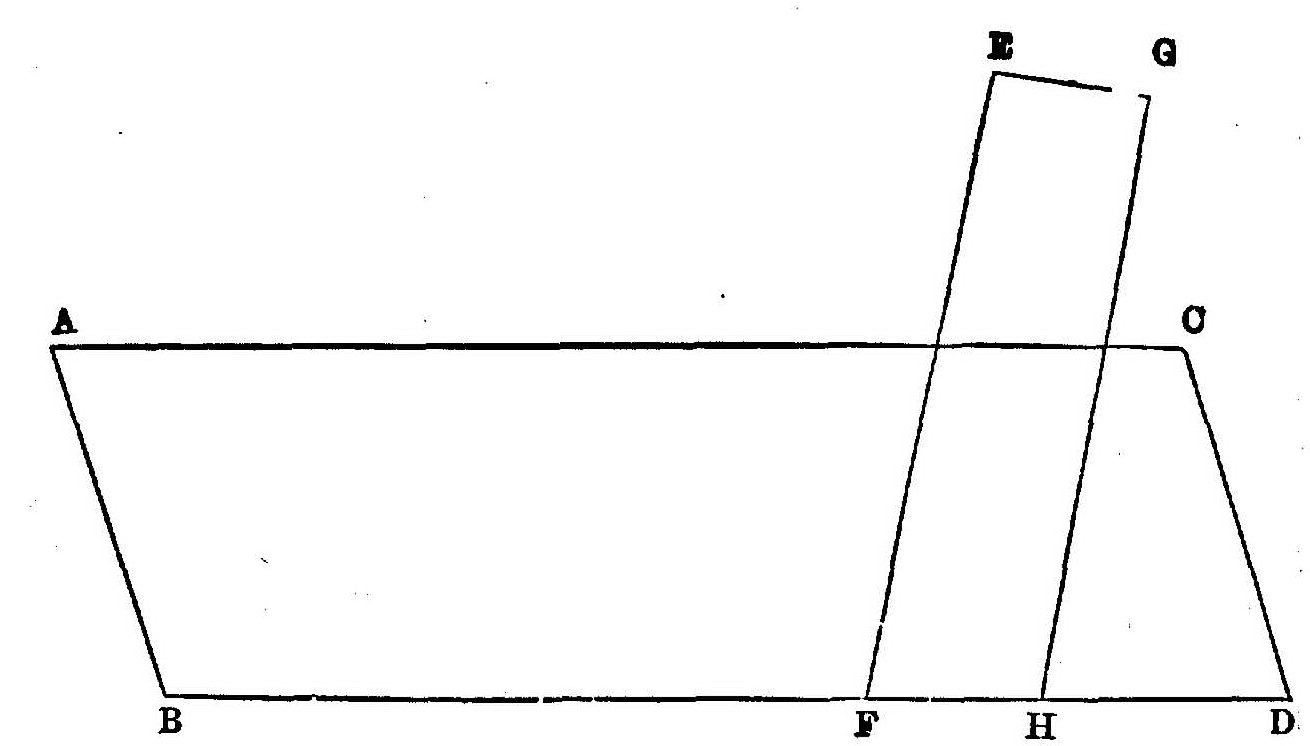

It was insisted at the trial, and is reurged forcibly in the motion for a new trial, that the court was in error in holding, as stated in the charge, that “in considering this issue [of parallelism] you will disregard the fact that the south end of the Champion claim extends beyond or is intercepted by the Pacific survey.” The contention of counsel, reduced to its essence, is that, whenever a location as surveyed and certified is intercepted by another valid claim going through it perpendicularly or obliquely, in the following form:

101

(A, B, C, D, representing the claim as located, and E, F, G, H, representing the intercepting claim.)

—then the end lines of the location are to be determined by the lines A B and E F. The said statute allows to the locator of any lode claim a length of 1,500 feet along the vein. It has been the custom to obtain this extent by locating over and across an intersecting claim, and in asserting the right of length the intersecting claim of course is excluded.

The construction contended for by plaintiffs would lead to this: that every time there was patented an intersecting slice through a location, although it left to the locator on either side of the patented strip unchallenged ground, the end lines to which are parallel, he must readjust his end lines so as to obtain his parallelogram without any interruption between the end lines; and if, in the mean time, between the original location and the amendment a lateral contiguous location has passed to patent, the contention of counsel is that the extralateral right to pursue the outcropping vein is gone irrevocably; and that even the doctrine of relation, referring back to the original entry, would not apply to save the right. I do not understand that such has been the recognized custom among miners, nor do I believe it executes the will of the statute. So in respect to the Belle of the East claim. It is true that the evidence shows that after the location of the Widow McCree claim the Belle of the East claimed that the north end of the former conflicted with the prior right of the latter, and so it was adjudged. Thereafter, and prior to the alleged trespass, this controversy was ended by the Belle of the East quitclaiming to the defendants. There was no interruption in the possession of the disputed territory occupied by the Widow McCree claim. Both prior and subsequent to that controversy the evidence tended to show the defendants had held and operated as one claim and system of development the Champion group, including the Widow McCree claim, as originally surveyed. The parallelism of the end lines of the Widow McCree claim was not practically disturbed. It seems to me that it 102would hew to pieces on the sharp edge of merest technicality defendants' apex rights, which they were prosecuting, by looking only at a fragment of the case instead of its essence in the entirety. But little question can be made that when defendants, as claimants of the Champion group, ask for a patent, it will be granted to cover the extent of the original Widow McCree location.

Severe criticism is made of that portion of the charge respecting the assault made by plaintiffs upon the discovery location on the Champion claim, All that was requested by plaintiffs defining the statutory requirements of location, the necessity of the discovery of mineral in place, was given in the charge. The qualification, if such it may be termed, put to this is found on page 791 of the reported charge. The statute of Colorado (sections 2399, 2401) provides for such location of certificates to the discoverer of a lode, and what shall be done by the locator before filing such location certificate, so that such certificate amounts to and imports something. The evidence on both sides tended to show the longstanding indications of a staked claim, and of shafts sunk or holes dug. The witnesses differed only as to the precise point of such workings. The claims had stood unchallenged for years, and work of more or less importance had been prosecuted at various points on these claims years before this controversy. If, after all this, the court should not tell the jury that every reasonable presumption should be indulged in favor of the discovery of a lode by the miner, it is difficult to conceive of a state Of facts where such intendment should arise. Any other rule, it seems to me, would render such claims practically unmarketable or valueless in the hands of an assignee. The miner goes, digs, and delves, and is so satisfied that he makes the survey, stakes off his claim, and then makes his location certificate, which is entered of record. After this he sells to an honest man, and passes out of view or dies. All the subsequent workings go to show the existence of a lode or vein on the claim of more or less importance. Can it be that after the lapse of many years the assignee must lose his claim because of his inability to produce the lost or the dead, and prove affirmatively au actual visible discovery by the original locator of ore in place where he dug? Possibly the charge in this particular would have been more theoretically correct had the court told the jury that it was not necessary that defendants should establish such discovery by witnesses to the physical fact at the time. But the same might be inferred from the certificate of location, the manifestations of workings done, the long tenure of the claim, the development of a vein on the claim by subsequent working, and from all the surrounding circumstances. In view of the actual proofs at the trial in this case, had the jury found for the plaintiffs on the ground of the lack of proof of an original discovery the court would have felt it to be its solemn duty to accord a new trial. Nor do I think even after “cocling time” that the language employed respecting “witnesses sent to these old opening, with their accumulated debris, to obtain evidence by inspection that no vein was in fact found by the original locators,” as also what was later on said respecting witnesses in general, was any too strong. Courts, so 103long as they are presided over by flesh and blood and mind, however weak or strong, must be expected to feel and think. Language, which is the vehicle of thought, with its seat in the heart, must reflect some tinge of the conviction of an earnest man; and while a proper judicial temper should be rigidly maintained, the judge on the bench should ever feel he is a minister of justice, and should not allow the truth to fail for lack of courageous action and frank utterance on his part. My observation at this trial satisfies me that an important mining litigation is a model training school for expert testimony; and if there ever is a case where the judge himself, like the witnesses in this case, should have the largest latitude of taking part in the discussion, it should be accorded in such cases, at least so far as it “is profitable for doctrine, for reproof, for correction.”

It is again urged, as at the trial, that the court should hold that, after the grant of a patent to the adjacent claimant, the right of the mere certificate holder to pursue his vein beyond his side lines is at an end; in other words, that this statutory right of the apex owner applies only as between certificate locators. Such, I am advised, has not been the holding of Judge HALLETT, whose opinion in mining law is justly entitled to great respect. Nothing short of a sense of the supreme command of the law could induce me to set up in this case a different ruling. Counsel has presented his view of this question with marked clearness and force. Without undertaking to review the authorities or his argument, it must suffice here for me to say that the statute contains no warrant for this position, unless it is to be found between the lines. The language of the federal statute (section 2322) in explicit terms declares:

“The locators of all mining locations heretofore made, or which shall hereafter be made, on any mineral vein, lode, or ledge situated on the public domain, their heirs and assigns, * * * shall have the exclusive right of possession and enjoyment of all the surface included within the lines of their locations, and of all veins, lodes, and ledges throughout their entire depth, the top or apex of which lies inside of such surface lines, extended downward vertically, although such veins, lodes, or ledges may so far depart from a perpendicular in their course downward as to extend outside the vertical side lines of such surface locations.”

The legislature of Colorado certainly entertains the view that the extralateral right exists without restriction in the mere holder of a certificate location. Section 2405, Gen. St., declares that—

“The location or location certificate of any lode claim shall be construed to include all surface ground within the surface lines there of, and all lodes and ledges throughout their entire depth, the top or apex of which lie inside of the side lines, extended downward vertically, with such parts of all lodes or ledges as continue by dip beyond the side lines of the claim.”

This, likewise, has ever been the view of the department of the interior, as evidenced by the expressed reservation from the grant in the patent. While of course this is not binding on the courts, as it is a matter of statutory construction, yet it is entitled to respect until otherwise affirmatively adjudicated. It might present a different question, if, 104after the patentee sunk a shaft from the surface to the underlying vein, and had taken actual possession of it, a subsequent certificate locator of the apex should undertake to oust the patentee. But that is not this case.

As to what is said in the brief of counsel touching the Champion group being regarded as one property, it seems to me to be sufficient to gay, the language of the charge does not justify the elaborate criticism. The court did not tell the jury that the holding of the several claims as one property, and prosecuting the work on any one as a system of development of the whole, would obviate the necessity of an original location, or cure substantial defects in parallelism. Judge BREWER refused to strike out of the answer averments in this particular, and I gave this matter such office in the charge as it seemed to deserve.

The action of the court on the effort of plaintiffs to get in evidence some map or survey, and affidavits used at some preliminary hearing, connected with the equity branch of this case, is assigned for error. According to my recollection of the first matter, plaintiffs offered a survey, or something of the kind, made out by some witness of the defendants, but not by defendants themselves. My further recollection is that the court observed that, without the testimony of the party who made this paper as to its correctness, he did not see how defendants could be bound thereby. It is possible that, if it had been shown that defendants had approved and used it, it would have been competent evidence, as being of the character of an admission of circumstantial fact, to go to the jury. But certainly, in view of all the surveys, maps, and diagrams before the jury from both sides, with all the witnesses before the court for examination and cross-examination, and no subsequent attempt by counsel to contradict any one by offering such survey or paper there for, the court cannot See or believe that any such evidence could possibly have changed the verdict; and, in respect to the affidavits or paper claimed by plaintiffs to be in possession of defendants' counsel, the history of what occurred at the trial will satisfy the judgment of counsel himself that the court is not in fault for the non-production of that paper. Counsel had taken the proper legal steps to bring the paper, whatever it was, into court, by giving notice to opposing counsel to produce it. When defendants' counsel was asked in court to produce this paper, the statement by the latter was that he had looked for it, and had not found it, but that he would examine further, and if he had it he would bring it into court without more. There the matter rested. The paper was not brought to court. It was expected by the court that before the case closed plaintiffs would again bring the matter up for some decisive action. If it had been shown to the court that defendants' counsel withheld the paper, on motion they would have been ordered to produce it, or been proceeded against for contempt, and plaintiffs would have been permitted to show the contents by parol. The matter afterwards passed out of the mind of the court, as it seemed out of that of plaintiffs' counsel. Certainly no error was committed by the court in this matter, as it was not asked to 105take any affirmative action therein. The plaintiffs had the benefit before the jury of the moral effect of what transpired in court relative to this incident.

Error is assigned on the action of the court in allowing defendants' counsel to open and close the argument to the jury. To properly understand this action of the court, a brief reference to the state of the pleadings is necessary. Owing to the particular character of the averments of the petition as to jurisdictional facts and the grounds of defendants' claim, a question of law arose at the outset as to whether or not the plaintiffs should not go so far in their proofs as to maintain these allegations. But the court soon became satisfied that the question of jurisdiction had been practically eliminated by the action of Judge Brewer in striking this issue from the answer, and later on a careful reading of the answer satisfied the court that it, in effect, admitted plaintiffs' title to the surface location of the Battle Mountain and Little Chicago claim, and directly admitted the invasion of the side lines of the plaintiffs' claim. Under the issues as they really stood, the only burden the law imposed upon plaintiffs was the mere formal introduction of the patent in evidence, and proof of the quantity and value of the ore taken. As it was not to the interest of defendants to disprove the presence of valuable ore at this point, the evidence on this issue was brief, and merely as to the value. If, forsooth, the plaintiff saw fit to extend this mere formal inquiry over a wider field, it was not demanded by the pleadings or by the court. It is manifest from the trial, the charge of the court, and this motion for new trial, that the real burden rested, and heavily, on the defendants. They held the laboring oar throughout on all vital issues in question. From them the burden of the real issue never shifted. Under such a peculiar condition of the trial, I felt that common fairness demanded that defendants' counsel should open and close the argument. This view of the real equity of the rule in question I have long entertained. I fought for it while at the bar, and shall endeavor to impartially maintain it, as one founded in justice and equality, while I remain on the bench.

My jurisdiction to pass upon this motion is called in question on the ground that I am not now acting under the order of Judge BREWER, which sent me to Colorado to hold circuit court in aid of the district judge. It was the pending litigation between these parties mainly which induced Judge BREWER to send me to Colorado, partly owing to the fact that Judge HALLETT wished to be relieved from sitting in the cause on account of his relation to some of the parties. The trial of the cause would have been incomplete without a final disposition of the motion for a new trial. The right to try the principal cause carries with it the incident. Had I remained at that court until the coming in of the motion for new trial, four days after the verdict, as I might well have done, no question could possibly arise as to my jurisdiction to pass upon the motion. Equally true must it be that I might have returned to Colorado after the motion was filed, and taken it up and decided it. Counsel for both parties having agreed to waive the necessity or burden of such 106trip to me, my right to pass upon this motion must be viewed as if I had gone to Colorado, or remained there in the first instance, to hear the motion. Unpleasant as it is to act under even the imputation of assuming authority, I feel constrained to proceed in this matter under an imperative sense of official duty. As the consideration of this motion involves not only a review of the questions of law in the case, but the complicated issues of fact, as well as the official and personal conduct of the trial judge, it at once becomes apparent that there is, almost a necessity that he should pass upon this motion, as also the bill of exceptions, if any, to be presented in the case. Respecting what has been brought in to the discussion on this motion touching indications of partiality at the trial, I may be indulged simply to say that both litigants and counsel on either side were entire strangers to me when the trial begun, and my acqucintanceship with them was limited to the court-room. If collisions between court and counsel occurred, it was doubtless attributable to mutual misconception. Two temperaments much alike, each impelled by a spirit of self-assertion, now and then produce antagonisms more apparent than real. I am satisfied that counsel did his duty, and did it well, on this trial; and no language could express my sense of regret if I felt there was any occasion for the thought that the scales of justice were unevenly held by the court. The court tried the case as best it could; and, if it erred to plaintiffs' prejudice, it will bring no regret to the court personally to see the wrong righted by an appeal to a higher court, or upon a subsequent trial, should the plaintiffs see fit to resort to either. The remedy being left to plaintiffs either to appeal or bring another action within a year, under the provisions of the Colorado statute, I feel the less hesitancy in following my judgment in denying the motion for a new trial.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.