HAMBLIN v. BISHOP.

Circuit Court, D. Delaware.

December 17, 1889.

v.41F, no.2-6

1. EQUITY—INSUFFICIENCY OF PROOF TO SUPPORT A DECREE FOR A RECONVEYANCE.

The defendant, who was tenant for life of a moiety of certain real estate, entered into negotiations with the tenants in common of the whole estate, including the complainant, for the purchase of their entire interest therein, and wrote to the complainant. “The heirsoin Bell's estate have all agreed to take $6,000,” and that, if she would sell her interest “the same as the others,” he would buy it. Relying on this representation she conveyed her share to the defendant. The proof was that two of the tenants in common had agreed, orally, with the defendant to sell their 75respective shares to him for the same consideration as the others, but did not convey their shares to him until nearly a year later. Complainant and defendant were of about the same age, and had equal means of acquiring a knowledge of the facts.Held that, under all the circumstances, there was not sufficient evidence to prove actual or constructive fraud, on which to base a decree for a reconveyance.

2. SAME—INADEQUACY OF PRICE.

A tenant for life of the undivided moiety of an estate purchased from the tenants in common of the land their whole interest, including the reversion, for $6,000. One of the tenants in common took in payment of his share ($1,000) of the consideration a small tract of land which had belonged to the estate, and which he sold, before conveyance to himself, for $1,425. Held, in the absence of evidence that the whole estate would have sold for more than $6,000, that inadequacy of price, sufficient to induce a court of equity to set aside the sale, was not proved. The fact that one tenant in common, on a resale of his share, had obtained an increased price for it, does not prove that an inadequate price was paid for the share of another tenant in common, or for the collective shares.

3. SAME—CONVEYANCE MADE UNDER A MISTAKE OF LAW.

One who was aunt of the half-blood, and cousin of the whole blood, to a decedent, having, in accordance with a legal opinion misinterpreting a Delaware statute, accepted as her portion of the intestate's real estate such portion only as she was entitled to as cousin, with the heirs of the half-blood excluded, while she was also entitled, by law, to a portion as aunt of the half-blood, and having, under erroneous advice, conveyed away her inheritance, has made a mistake of law, and not a mistake of mixed law and fact, and will not be relieved, in a court of equity, by a decree for a reconveyance, especially where the parties cannot be placed in statu quo.

Bill in Equity by Hannah M. Hamblin, against James R. Bishop, to Compel Reconveyance.

Anthony Higgins and H. F. Hepburn, for complainant.

Geo. V. Massey and Chas. Moore, for defendant.

WALES, J. This suit was brought to compel the defendant to reconvey to the complainant certain real estate in Sussex county, Del., which she had been induced to sell and convey to him, as she alleges, by fraudulent misrepresentations on his part, and also because, at the time of her conveyance to him; she was mistaken about the quantity of her interest in the land; her interest being much in excess of that which she had intended to convey, and of what she then knew or believed she was entitled to. She further alleges that the price paid by the defendant was grossly inadequate, and greatly below the actual value of the interest purchased by him.

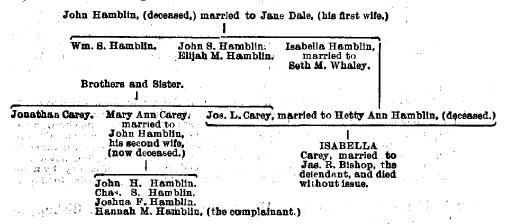

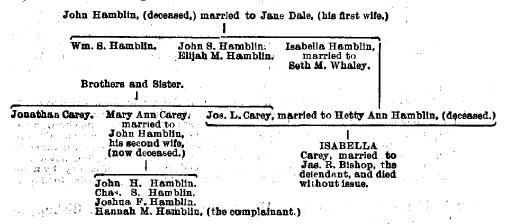

The facts, as disclosed by the bill, answer, and proofs, are these: On the 26th of January, 1880, Isabella Bishop, the wife of the defendant, died intestate, seised and possessed of four tracts of land in Sussex county, Del., containing in all 578 acres. The said Isabella died without issue, never having had any children, and without brothers or sisters, father or mother, her surviving, but left to survive her her husband, James R. Bishop, the defendant, and the following collateral heirs and next of kin, to-wit: On the maternal side, three uncles and one aunt of the whole blood, as follows: William S. Hamblin, John S. Hamblin, Elijah M. Hamblin, Isabella Whaley, wife of Seth M. Whaley, and three uncles and one aunt of the half-blood, as follows: Joseph H. Hamblin, Charles S. Hamblin, Joshua T. Hamblin, and Hannah M. Hamblin, the complainant herein; and, on the paternal side, an uncle of the whole blood, Jonathan Carey, and the issue of a deceased aunt of the whole blood, Mary Ann Carey, who intermarried with Captain 76John Hamblin, to-wit: Charles S. Hamblin, Joseph H. Hamblin, Joshua T. Hamblin, and Hannah M. Hamblin, the complainant, being the same persons occupying the relation of uncles and aunt of the half-blood as aforesaid. These persons comprise all of the collateral heirs of Isabella Bishop living at the time of her decease, and who were her only heirs at law, as appears from the annexed table of descent:

Two days after the funeral of Mrs. Bishop, the complainant, together with her three whole brothers, and her uncle Jonathan Carey, and some of the other parties above named, met at the house of the defendant in Selbyville, to confer about the distribution or allotment of the estate. This conference ended in an appointment to meet at Georgetown, and take legal advice in regard to a settlement of the rights of all the parties, and accordingly the complainant, with two of her whole brothers and her uncle Jonathan, met at Georgetown early in February, probably the second of the month, 1880. Some of the other heirs were present at this meeting, either in person or by their representatives. A lawyer was employed, and the relationship of all the parties to Mrs. Bishop having been fully stated and explained to him, it was then and there understood, and the parties present were so advised, that James R. Bishop was entitled to all the personal property of his deceased wife, absolutely, anal to one-half of her real estate in Delaware for his life; that the uncles and aunts of the whole blood were entitled to all the real estate in fee, subject to the life-estate of James R. Bishop in the one-half; the issue of a deceased aunt of the whole blood taking the share of their mother by right of representation. By this rule of apportionment, the real estate being divided into six equal parts, corresponding to the number of uncles and aunts of the whole blood, including a deceased aunt, one-sixth, would belong to each uncle and aunt living at the time of Mrs. Bishop's death, and the remaining sixth would be subdivided among the children of the deceased aunt of the whole blood; thus excluding the collateral heirs of the half-blood from any share in the estate. The complainant, therefore, was informed and believed that she would be entitled, as a cousin of Mrs. Bishop, to one-fourth of one-sixth part,—that is, to one twenty-fourth part of the estate; and that she was not entitled 77to any share as an aunt of the half-blood. There had been some discussion among the heirs, at their first conference, about the value of the real estate, which was suggested by the proposition that the defendant should buy the whole, but no definite conclusion was then reached. After obtaining the opinion of counsel, and when the heirs had, as they believed, ascertained the extent of their respective shares, the negotiations for a sale to the defendant were renewed, and it was finally agreed that they would convey all their interest to him in fee for the consideration of $6,000. In pursuance of this agreement, all of the heirs excepting William and John Hamblin conveyed their shares, being their entire interest in the estate, to the defendant, between May 7 and July 27, 1880, the complainant's deed bearing date on the day last named. The deeds from William and John were not executed until April 29 and May 16, 1881. Each of the uncles and the aunt of the whole blood received $1,000 in cash excepting William and John Hamblin, and each of the four children of the deceased aunt of the whole blood, including the complainant, received $250. William and John Hamblin had bargained with the defendant to take, in lieu of cash, for their respective shares, conveyances of land of equal value, in money.

| RECAPITULATION. | |

| Jonathan Carey was paid in cash, | $1,000 00 |

| Elijah M. Hamblin “ “ “ | 1,000 00 |

| Isabella Whaley “ “ “ | 1,000 00 |

| Joseph H. Hamblin “ “ “ | 250 00 |

| Charles S. Hamblin “ “ “ | 250 00 |

| Joshua T. Hamblin “ “ “ | 250 00 |

| Hannah M. Hamblin “ “ “ | 250 00 |

| William S. Hamblin “ “ land, | 1,000 00 |

| John S. Hamblin “ “ “ | 1,000 00 |

| Total, | $6,000 00 |

The land sold by the defendant to William and John Hamblin, in exchange for their shares, consisted of that portion of Mrs. Bishop's estate called the “Burton Farm,” containing 122 acres. One-half of this tract was conveyed to William, and the other half was conveyed to Joshua S. Stevens, who was the appointee of John Hamblin. The consideration mentioned in the deed to Stevens was $1,425, but the defendant had sold to John for the sum of $1,000, and whatever sum was paid by Stevens in excess of $1,000 was paid to John Hamblin and not to the defendant.

To establish the charge of fraud and misrepresentation, reliance is placed in the fact that the defendant, on June 11, 1880, wrote to the complainant, who was then residing in Philadelphia, “that the heirs in Bell's estate have all agreed to take $6,000 for their part of the real estate in Delaware, and I have wrote two or three times in regard to yours, but have not yet received any answer. If you will sell me your interest in the land, the same as the others, I will come up and get the deed and pay you for it. You can consider the matter and let me know.” In further support of this charge, attention is also called to the admission 78of the defendant, in his testimony, “that he thought it likely he had told the complainant, prior to her conveyance to him, that William and John Hamblin had sold their shares to him, though he had no particular recollection of doing so.”

The proof of fraud, therefore, depends on these two facts. The evidence, after a careful examination, furnished no others. Are these sufficient to produce the conviction that the defendant intended to cheat and defraud the complainant? Was he guilty of actual or constructive fraud? Did he intentionally, or otherwise, mislead the complainant? These two persons were about the same age. The defendant was 25 years old on the 25th of April, 1880. They had been long acquainted, and the most friendly relations existed between them. They stood on equal terms in reference to the knowledge of their respective interests in Mrs. Bishop's estate; possessed equal means of knowing each step that had been taken or agreed on by her co-heirs in the settlement of their rights. She had resided in Sussex County during the earlier portion of her life, and had made annual or more frequent visits to her relatives in that county after she had gone to reside in Philadelphia. She had been informed by a letter, received from her brother Charles under date of May 17, 1880, of what had been done up to that time, in these words:

“Hannah, we, Charles, Joshua, Joseph, Elijah, have this day sold to James Bishop all of our right, title, claim, which we hold in Bell Bishop's estate in the state of Delaware, and received pay for the same.”

There is no controversy over the truth of the defendant's statement in his letter of June 11, 1880, that all the heirs in Delaware had agreed to take $6,000 for their interest, meaning at the rate of $6,000 for their respective interests in fee-simple; nor is it denied that, he had paid all of them, excepting the complainant and her half-brothers, William and John, before she conveyed her share to him. There had been no written articles of agreement between the defendant and any one of the heirs. The contracts for sale had been made orally, and, when he stated to the complainant that all the other heirs had sold to him, he was telling what lie believed, to be the truth, and his statement was fully confirmed by the subsequent conveyances from William and John Hamblin. In common parlance, when a person says that he has bought a piece of real estate from another, he cannot be held guilty of falsehood, if, at the time of making such declaration, the contract of sale and purchase has been made, although no conveyance of the property has been formally executed. There was no intentional or constructive fraud on the part of the defendant in making the statement he did in reference to the shares of William and John Hamblin; and there is no proof, in all the voluminous and largely irrelevant testimony in this cause, that he intended to, or that he did, deceive the complainant in order to obtain her deed; on the contrary, the attempt to show that the complainant was the victim of fraudulent misrepresentations and unfair dealing has entirely failed. That the defendant desired to buy her share and procure her deed, after he had bought out the other heirs, was natural enough, and he used no improper means to accomplish that purpose. Neither William 79nor John Hamblin has been produced to contradict the defendant's statement of their sale to him, nor is it satisfactorily proved that the complainant would have declined to make her deed of July 27, 1880, if she had then known that her half-brothers, William and John, had not yet formally executed their deeds to the defendant. She went to Sussex county in July, 1880, and, was visiting among her relatives and connections for two weeks before the date of her deed, and had every opportunity of acting with knowledge and deliberation. Any contrivance on the part of the defendant to deceive or defraud her, under such circumstances, would have been futile. The charge of fraud, therefore, is not sustained.

Another ground assigned for a reconveyance is the gross inadequacy of the price paid by the defendant. The sale of Mrs. Bishop's estate was not a forced one. Negotiations for the sale had been pending from early in February to the 7th of May, 1880, and ample time had been afforded to make an estimate of and fix the market value of the property. Two modes of settlement were open,—the one that was adopted, and the other by proceedings, in the orphans' court for the assignment to each heir of his respective portion, or, if such division should be found to be, impracticable, then by an order of public sale, the proceeds of which would represent the land, and be divided among the heirs according to law. To save expense and delay, the first plan was considered the more advantageous, and was carried into effect. All of the heirs lived in the neighborhood of these lands, and were more or less acquainted with them, the complainant haying resided for the greater part of; her life in the same vicinity, Jonathan Carey, if pot all of the uncles of Mrs. Bishop, was familiar with the value and productiveness of such property. They had to estimate the value of this whole estate, subject to the life-tenancy of a very young man in the, one-half of it. Some parts of the land; were swampy and uncultivated, and would require no small outlay of money for clearing off wood and ditching. The sellers wanted the highest price, and the buyer the lowest price. The amount was at last agreed on, and the sale made. Gross inadequacy of price, under circumstances which raise the presumption of fraud or imposition, will sometimes furnish good reason for equitable relief; but even then the price must be so disproportioned to the actual value of the property sold as to shock the sense of justice. No disproportion of this kind existed here. The advanced price, mentioned in defendant's deed to Stevens as having been paid by the latter to John Hamblin for the 61 acres of the Burton farm, falls short of the full proof required to establish such an inadequacy of price for which equity will set aside a sale otherwise fairly and honestly made; and there is not the slightest evidence that any person was willing and ready to pay more than $6,000 in cash for the whole estate, subject to the life-tenancy of the defendant. Moreover, the fact that John Hamblin, on a resale of his share, obtained a considerable advance, does not prove that an inadequate price was paid to the complainant for her share, or for the collective shares.

The remaining question to be considered is, was there such a mistake 80of law committed by these parties, under all the circumstances surrounding the sale of Mrs. Bishop's estate, that a court of equity is bound to give relief from its consequences to this complainant, who is the only one of the defendant's grantors who is now demanding a reconveyance. The general rule, both at law and in equity, is that a conveyance, unaccompanied by fraud or imposition, will not be set aside for a mistake of law. Contracts and conveyances have been canceled or reformed to correct a mistake of fact, or in order to carry out the intention of the parties, but where there has been a mutual and plain mistake of law, the interference of a court of equity has been rare and exceptional. Conflicting opinions of able judges may be found on the meaning and application of the maxim, ignorantia juris non excusat, but the current of authorities in this country is in favor of enforcing the rule as just stated. Some learned jurists have assumed the position that the maxim was designed to apply to violations of the criminal law only, and that it should not prevent the rectification of a mistake, when a person has ignorantly disposed of his private right of property. Various nice distinctions and refined reasoning have been employed to relax the stringency of the rule, and counsel for complainant have referred to respectable authorities, both in this country and in England, to sustain their theory that the present case affords the example of a mixed mistake of law and fact, for which the relief now sought for has been granted. In Freeman v. Curtis, 51 Me. 140, it was held that money paid or other property conveyed under a mistake of law, with full knowledge of the facts, cannot be recovered back; but in that case the defendant had paid no consideration for the property, and, being also guilty of deception, a reconveyance was ordered. It is true that in that case the plaintiffs were ignorant of the law relating to the descent and distribution of estates, and this ignorance of the law involved them in a mistake of fact as to who were the heirs of H. Curtis; and the court said: “Where the mistake is one both of law and fact, though the latter is the result of the former, relief will be granted when justice and equity require it.” The doctrine thus laid down might be accepted as sound, when all the parties who had lost or gained by the mistake could be restored to their original condition in relation to the property affected; but it may be considered more in the light of a dictum than of an adjudication, since the case was decided on other and different grounds. The maxim ignorantia et cet. is founded on the presumption that every person is acquainted with his own rights, provided he has had a reasonable opportunity to know them, and on a long experience of the dangerous and embarrassing results that would follow if ignorance of the law should be recognized as a sufficient cause for the annulment of contracts which have been executed by a complete performance. 1 Story, Eq. Jur. § 111; Bilbie v. Lumley, 2 East, 469. What was the mistake made by the parties in this cause? The complainant was both a cousin of the whole blood and an aunt of the half-blood of Mrs. Bishop. It is admitted that, at the time when the complainant executed her deed, she believed that she was entitled to a one-twenty-fourth part of the estate only, as a cousin-german of the decedent, and that she intended to convey 81that much and no more of her interest to the defendant. It is also admitted that the defendant believed that he was purchasing from her the share to which she was entitled as a cousin, and that both were alike ignorant that by law she was also entitled to an additional share of four-fortieths as an aunt. This mistake arose from the incorrect advice of the counsel who was consulted by the heirs, or from a misunderstanding of that advice. In either case both parties acted in ignorance of the provisions of the statute of Delaware, which directs the transmission of the estate of a decedent who dies intestate, leaving only uncles and aunts, or the issue of a deceased uncle or aunt, to survive her. The statute provides that in such cases the estate shall descend—

“To the next of kin in equal degree, and the lawful issue of such next of kin by right Of representation: provided, that collateral kindred claiming through a nearer common ancestor shall be preferred to collateral kindred claiming through a more remote common ancester.” Rev. St. Del. c. 85, § 1.

The same section, in a preceding part of it, provides that the decedent's brothers and sisters of the whole blood shall be preferred to the brothers and sisters of the half-blood. It was doubtless the misapprehension of this rule of preference of the whole blood, when the estate devolved on brothers and sisters, that led to the mistaken construction of that part of the statute above quoted, and by which the heirs had been instructed that their interests were determined. But this portion of the statute had long before received a judicial interpretation in McKinney v. Mellon, 3 Houst. 277, which settled all question of its meaning. It was there decided that—

“The half-blood are entitled to, and must be admitted to share in, the distribution in equal degree with the whole blood in all cases where they are not, by express statutory provision, excluded by preference conferred by it upon others. This our statute has only done in preferring brothers and sisters of the whole blood to brothers and sisters of the half-blood.”

The construction given to this statute by the lawyer who was consulted by the heirs excluded the uncles and aunt of the half-blood from any share of the estate, and hence the mistake, which was a plain and simple mistake of law, made with a full knowledge of all the facts of relationship and degree of consanguinity of the defendant's grantors to Mrs. Bishop. Can it be said with any propriety that this mistake was one of fact, or of mixed fact and law? On this point it has been observed that, where there is a plain and established doctrine, so generally known as the common canons of descent there, a mistake in ignorance of the law, and of title founded on it, may well give rise to a presumption that there has been some undue influence, imposition, mental imbecility, surprise, or confidence abused. But in such cases mistake of the law is not the foundation of the relief, but it is the medium of proof to establish some other ground of relief. 1 Story, Eq. Jur. § 128.

As already said, there has been much discussion of the question when and how far a court of equity will go in granting relief from a mistake of this kind; but it will not be necessary or useful to renew that discussion here, or to review the numerous authorities that are to be found in 82the text-books, Lansdowne, v. Lansdowne, 2 Jac. & W. 205, so much relied on by the complainant's counsel, has not been accepted as the law of this country, nor has it been uniformly received as a controlling authority in England. In that case the court relieved the plaintiff from a mistake of law which he had committed under the advice of a layman; but the facts which were before the court have not been fully reported, and the decision has beep criticised and doubted. It is enough for the present purpose to know that the question was clearly presented and considered in Bank v. Daniel, 12 Pet. 32, in which the court states the principle involved in the case in these words:

“The main question on which relief was sought by the bill, that on which the decree below proceeded, and on which the appellees rely in this court for its affirmance, is, can a court of chancery relieve against a mistake of law?”

After a discussion of the evidence, and a reference to the confusion created by numerous and conflicting decisions, the court reaffirms its decision in Hunt v. Rousmaniere's Adm'rs, 1 Pet. 15, and concludes with this language:

“Testing the case by the principle ‘that a mistake or ignorance of the law forms no ground of relief from contracts fairly entered into, with a full knowledge of the facts,’ and under circumstances repelling all presumptions of fraud, imposition, or undue advantage having been taken of the party, none of which are chargeable upon the appellants in this case, the question then is, were the complainants entitled to relief? To which we respond decidedly in the negative.”

The court had previously said, in Hunt v. Rousmaniere's Adm'rs—

“That whatever exceptions there may be to this rule, [that mistakes arising from ignorance of law are not relievable in equity,] they are not only few in number, but they will be found to have something peculiar in their character, and to involve other elements of decision.”

In commenting on these two cases, an eminent jurist has remarked that, “so far as the courts of the United States are concerned, the question may be deemed finally at rest.” 1 Story, Eq. Jur. 148.

The estate of Mrs. Bishop ($6,000) should have been divided into 40 shares, and distributed as follows: Four shares to each uncle and aunt living at the time of her death, and one share to each of the four children of Mary Carey Hamblin, the deceased aunt. Under that arrangement, the complainant would have received four shares as an aunt, and one share as a cousin. Through her ignorance of the law, without any fault of the defendant, she has been deprived of four shares, a loss which the court cannot restore to her. This may entail some hardship on her, but, on the other hand, if the court was at liberty to order, and should make, a decree for a reconveyance, a still greater hardship would be inflicted on the defendant. A court of equity is always reluctant to rescind a contract, unless the parties can be put back in statu quo; and if this cannot be done, it will give relief only where the clearest and strongest equity imperatively demands it. Grymes v. Sanders, 93 U. S. 62.

The equities in this case being equal, the existing conditions of the defendant and complainant should not be disturbed. The defendant, 83after he had acquired possession of the estate, began at once to lay out money in improving the property, which he did quite extensively. The distribution of the money paid by him to the heirs was made under a mistake of law, due to the common ignorance of all the parties concerned in the settlement. Justice and equity would appear to require a redistribution, but this cannot be ordered under the present proceedings; and whether, at this late day, the complainant could successfully demand a contribution, from each one of the heirs who was overpaid, to make good her loss, is a question not now before the court.

Let a decree be entered dismissing the bill.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.