BEASLEY v. WESTERN UNION TEL. CO.

Circuit Court, W. D. Texas, San Antonio Din.

May 29, 1889.

1. TELEGRAPH COMPANIES—NEGLIGENCE.

If a message is written by the sender on a telegraphic blank containing stipulations restrictive of the right of recovery in case of negligence in the transmission of the message, he is bound by such stipulations whether he reads them or not; no fraud or imposition being used to prevent him from acquainting himself with their purport.

2. SAME.

A stipulation requiring a claim for damages for such negligence to be presented in writing within 30 days is valid, and, no reason being shown for failing to present it, no recovery can be had.

3. SAME—AUTHORITY OF AGENT.

Although a telegraph company's rules prohibit its agents from receiving messages written otherwise than on its printed blanks, a sender ignorant of the prohibition is not bound thereby, and hence where the agent, without the sender's request, copies a message written on ordinary paper onto a blank, the sender will not be bound by the stipulations in the blank.

4. SAME.

A telegraph company is held only to reasonable care and diligence in the transmission of messages, and if stress of weather prevents their being sent by the usual and most direct route, the company is not chargeable with negligence by selecting the next best available route.

5. SAME.

It is no excuse for delay in transmiting a message that an agent at an intermediate point was in doubt as to its proper destination, the message being addressed to “Wallace” instead of “Wallis,” there being no place in the state of the former name, if he knew of the existence of the latter town, and failed to send it to that point.

1826. SAME.

If the error in the name was chargeable to the agent who received the message from the sender, the company would be liable, regardless of the diligence used by the agent at the intermediate office to discover the correct destination.

7. SAME.

Where the message alleged to have been unreasonably delayed contained information of the probable death of plaintiff's wife, and the only means by which, if the dispatch had been duly received, plaintiff could have arrived before her death was by a train which passed at a distance of 15 miles from the point to which the message should have been sent, within 2 hours and 15 minutes after the earliest time at which he could have received the message, it is for the jury to decide whether he could have reached her while living, and therefore whether he was injured by the delay.

8. SAME—DAMAGES.

The recovery in such a case is measured by a proper compensation for the disappointment and anguish suffered by plaintiff's inability to be with his wife before her death, no punitive damages being allowed, nor should the grief naturally arising from the wife's death enter into the determination of the amount awarded.

At Law; Action for damages.

Tarleton & Kellar, for plaintiff.

John A. & N. O. Green, for defendant.

MAXEY, J., (charging jury.) The plaintiff, Robert Beasley, brings this suit to recover damages of the defendant for the failure to deliver a telegram to him at Wallis, a station on the San Antonio & Arkansas Pass Railway. The message, alleged in the petition to have been delivered by Miss Annie Melas, as agent of plaintiff, to the defendant's operator at San Antonio for transmission, is set out as follows:

“SAN ANTONIO. TEXAS, JANUARY 11, 1888.

“To Robert Beasley, News Agent, 8. A. & A. P. Ry. train, Wallis, Texas:

“Dell is worse, come at once.

[Signed] “SISTER ANNIE.”

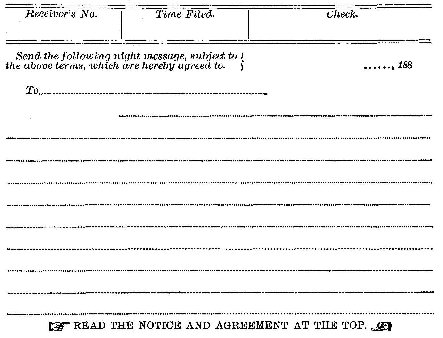

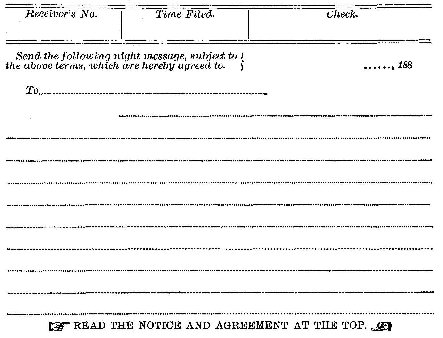

The telegram has reference to the wife of plaintiff, who (the wife) was then in a critical condition, and who died on the morning of the 11th, and, as stated by Miss Melas, between the hours of 11 and 12 o'clock. Referring to that telegram, it is alleged by the plaintiff “that said message was written by said Annie Melas upon a half sheet of common commercial note paper, and when the same was delivered, as aforesaid, to the agent of defendant, he, the said agent, of his own volition, and without the request of the said Annie Melas, copied, or rewrote, said message upon one of the telegraphic blanks of said defendant.” It is insisted, on the contrary, by the defendant that Miss Melas herself wrote the body of the message, including the signature, and that at her request the agent of defendant, Towhey, merely inserted the address, and that Miss Melas so wrote the message on one of the printed forms or blanks which are in general use by the defendant company; the same being as follows: Form No. 46.

THE WESTERN UNION TELEGRAPH COMPANY.

NIGHT MESSAGE.

The business of telegraphing is subject to errors and delays, arising from causes which cannot at all times be guarded against, including sometimes negligence of servants 183and agents whom it is necessary to employ. Errors and delays may be prevented by repetition for which, during the day, half price extra is charged in addition to the full tariff rates.

The Western Union Telegraph Company will receive messages, to be sent without repetition during the night, for delivery not earlier than the morning of the next ensuing business day at reduced rates, but in no case for less than twenty-five cents tolls for a single message, and upon the express condition that the sender will agree that he will not claim damages for errors or delays or for non-delivery of such messages, happening from any cause, beyond a sum equal to ten times the amount paid for transmission; and that no claim for damages shall be valid unless presented in writing within thirty days after sending the message.

Messages will be delivered free within the established free delivery limits of the terminal office. For delivery at a greater distance a special charge will be made to cover the cost of such delivery, the sender hereby guaranteeing payment thereof.

The Company will be responsible to the limit of its lines only, for messages destined beyond, but will act as the sender's agent to deliver the message to connecting companies or carriers, if desired, without charge and without liability.

THOS. T. ECKERT, GENERAL MANAGER.

NORVIN GREEN, PRESIDENT.

You observe a clause in the printed form to the effect “that no claim for damages shall be valid unless presented in writing within thirty days after sending the message;” and the evidence, without contradiction, clearly showing that no claim for damages was made until the following July, about six months after the death of the wife, the defendant contends that the suit is not maintainable. There is evidence tending to show that Miss Melas did not read the printed matter of the company's form, and was ignorant of its contents. Whether Miss Melas wrote the message or the body of the message on the printed form furnished by the defendant is a question of fact which you will determine from an examination of all the facts and circumstances in evidence. If she did thus write the message,—if she wrote it on a form containing the stipulation 184which I have read to you as to the time for presenting a claim for damages,—there are certain principles of law bearing upon that question which it becomes necessary for me to call to your attention.

1. It is immaterial whether Miss Melas read the printed matter or not. Upon this point the supreme court of this state say:

“The sound and practical rule of law in such cases is that in the absence of fraud or imposition a party to a contract, which has been voluntarily signed and executed by him, with full opportunity for information as to its contents, cannot avoid it on the ground of his own negligence or omission to read it.” Womack v. Telegraph Co., 58 Tex. 179.

In the same connection the court quote the following extract from an opinion delivered by the supreme court of Michigan:

“This printed matter on the face of the paper could hardly escape the attention of any one not naturally or purposely blind who should write a message upon the paper. He must at least know that there is some printed matter on the face of the paper, and he must be held to know that it had been placed there for some purpose connected with the message. It is therefore no excuse for him to say he did not read the printed matter before his eyes. It was gross negligence on his part if he did not. The printed blank, before the message was written upon it, was a general proposition to all persons of the terms and conditions upon which messages would be sent. By writing the message under it, signing and delivering it for transmission, the plaintiff below accepted the proposition, and it became a contract upon those terms and conditions.” Id. 180; citing Telegraph Co. v. Carew, 15 Mich. 536. See, also, Telegraph Co. v. Neill, 57 Tex. 285 et seq.

I do not say, gentlemen, that Miss Melas was guilty of gross negligence in failing to inform herself of the contents of the printed form, but her want of knowledge, under the circumstances, is due to her failure to avail herself of the opportunity she had of obtaining the information, and she and the plaintiff, for whom she was acting, are chargeable with knowledge of what the printed form contained.

2. As before stated to you, the printed form provides that no claim for damages, unless presented in writing within 30 days, shall be valid. Referring to a stipulation of that character in a printed telegraphic blank form, the supreme court of this state, speaking through Mr. Justice STAYTON, say: “Agreements of this character are held to violate no rule based on public policy, and to be reasonable and obligatory.” Telegraph Co. v. Rains, 63 Tex. 28. The testimony in this case shows that the plaintiff, at the time of the death of his wife, resided in San Antonio; that his wife died on the 11th of January; that he reached his home on the night of the same day; and that within three or four days thereafter he was shown by his sister-in-law the message which she says she delivered to Towhey. He therefore had ample time to present his claim for damages to the defendant, and no reason is disclosed or attempted to be shown by the testimony for his failure to present it within the 30 days. You are instructed, therefore, that if Miss Melas wrote the body of the message on the printed form, to which you have been referred, and requested Towhey to write the address, then the plaintiff is not entitled to maintain this suit, and you will find in favor of the defendant. If, however, you conclude 185from the testimony that, as alleged in the petition, Miss Melas delivered to Towhey a message on note paper, addressed to plaintiff at Wallis, for transmission, and that Miss Melas and Towhey made an agreement for transmitting the message, so delivered by her, for the sum of 30 cents, and that Towhey afterwards, of his own volition, and without request of Miss Melas, copied the message on a printed form of the defendant, without directing her attention to what the form contained, then the plaintiff would not be bound by the conditions and stipulations of the printed matter found on the form; and, in that event, you will proceed further and consider other questions affecting the plaintiff's right to recover.

In connection with the delivery of the message by Miss Melas and its receipt by Towhey your attention will be directed to certain printed rules and regulations of the defendant introduced in evidence. Counsel for defendant insists that those rules prohibit its agents (operators) from receiving a message unless it be written on a company printed blank. That may be true, and yet the prohibition would not prejudicially affect a third party, who had, in ignorance of the rules, made a contract or agreement with an agent for sending a message. If an authorized agent of the defendant—and you are instructed that Towhey had full power to act for the defendant in contracting for the transmission of messages (Telegraph Co. v. Broesche, 10 S. W. Rep. 735, 736)—receives a message from a person written on note or other kind of paper, and agrees for a stipulated consideration to transmit the message to its destination, the defendant would be bound by such agreement; and the fact that the message had not been written on a printed blank would be immaterial, unless the sender had actual notice of the prohibitory rule. If the rule of law were otherwise, a telegraph company could effectually escape liability for the negligence of its agents by merely providing them with printed rules. I cannot adopt that view of the law, so repugnant in my judgment to reason, and so contrary to sound public policy; and, if you find that Towhey did agree with Miss Melas to send the message in manner and form as claimed in the petition, it will be your duty to determine whether the defendant exercised due care and diligence in the effort made to transmit it to the plaintiff.

Touching the duties which telegraph companies owe to the public, and the degree of care required of them in the performance of their duties, the supreme court of this state use this language:

“The great weight of authority, and which, from the nature of the employment of telegraph companies, seems founded upon reason, is that, though in some essential particulars they partake of the chancier of common carriers, they are not strictly such, and should not be held to the same degree of strict responsibility. * * * As our legislature, however, has delegated to telegraph companies the power to exercise the right of eminent domain, and as their employment is quasi public, they should so far be governed by the law applicable to common carriers that the general duty devolves upon them to serve the public and act impartially and in good faith to ail alike, and to send messages in the order received. But they are not, as is the general rule with common carriers, insurers, simply by reason of their occupation, but are held 186only to a reasonable degree of care and diligence in proportion to the degree of responsibility.” Telegraph Co. v. Neill, 57 Tex. 288.

It was therefore the duty of defendant's agents to exercise a reasonable degree of care and diligence, considering the importance and urgency of the message intrusted to them, in sending the telegram forward to the plaintiff. Was such diligence exercised by Towhey and the agents at Dallas and Galveston? Your attention is drawn to the places named particularly for the reason that, because of the prevalence of “sleet storms” at that time, the direct line connecting San Antonio and Galveston was out of repair, and it thus became necessary for the defendant to transmit the message by the more circuitous Dallas route. No negligence can be imputed to the defendant, growing out of the impaired condition of the wires between San Antonio and Galveston, as it resulted from causes altogether beyond its control.

But the question remains for you to consider, was due diligence used to deliver the message to the plaintiff via the Dallas line? The message, you will remember from the testimony, was delivered to the agent, Towhey, at San Antonio, Miss Melas testifies, between 12 and 1 o'clock, 10th or 11th of January, and Towhey, about 1:35 A. M. on the 11th. It is shown by the testimony of the defendant that the message was received at Galveston at 2:15 A. M. on the 11th, and delayed there until 10:41 A. M. of that day. To account for the delay at Galveston it is insisted by defendant that the telegram was addressed to plaintiff at “Wallace,” when it should have been “Wallis,” and, there being no such place in the state as “Wallace,” it became necessary for the Galveston office to ascertain from the office at San Antonio the point or place to which the message should be transmitted. And defendant's counsel further insist that, owing to the lateness of the hour at which the message was received at Galveston, and the crowded business condition of the wires, the inquiry could not be made of the San Antonio office until the next morning. Now, as to the misspelling of the name of Wallis you should regard that as immaterial, if the defendant's agents, by reasonable diligence, could have seasonably transmitted the message to the plaintiff at the place spelt and known as “Wallis.” Although there may not have been a place in the state spelt “Wallace,” yet the two names are pronounced alike,—the pronunciation is the same, the only difference being in the terminal letters of the names,—and if the agents knew of “Wallis” it was their duty to send the message to that point, and, failing to reach the party to whom it was addressed, then they should have made further inquiry as to the proper place. Again, if Towhey, as the plaintiff contends, was responsible for the mistake, the misspelling of the name,—and of that you must judge from considering the testimony,—then his mistake would be chargeable to the defendant, and in that event it would not be necessary to inquire into the conduct of the agents at Galveston, for although they may have exercised the highest degree of diligence, still, if the delay at Galveston originated in the fault and negligence of the San Antonio agent, the defendant would be liable to the plaintiff for any injuries which may have resulted directly from that negligence. Whether due diligence was exercised 187by defendant's agents is a question solely for you to determine, and in deliberating upon that question you should consider all the facts and circumstances in evidence, and come to such conclusion as will be just, fair, and reasonable as between the parties to the suit. If the defendant, through its agents, exercised reasonable care and diligence in the performance of the duty which it owed the plaintiff in respect of transmitting the message to him, it would not be liable in this suit, although the message may not have been delivered at Wallis in time for the plaintiff to have reached his home and been with his wife before her death. If, however, it was negligent in the performance of its duty, you will inquire whether such negligence caused or resulted in damage to the plaintiff. It is not every act of negligence that gives a right of action. Upon this point the rule is thus stated by the supreme court of this state:

“It maybe laid down as a true proposition that bare negligence, unproductive of damage to another, will not give a right of action; negligence causing damage will do so.” Hallway Co. v. Levy, 59 Tex. 567; Telegraph Co. v. Broesche, 10 S. W. Rep. 736; Womack v. Telegraph Co., 58 Tex. 181.

Now, were the injury and damage of which the plaintiff complains the direct result of negligence on the part of the defendant's agents? Upon this branch of the case it will be necessary for you to carefully look into the evidence. The defendant left San Antonio on the 10th of January for Wallis, and reached the latter place at 3:20 A. M. on the 11th. His wife died, according to the testimony of Miss Melas, between 11 and 12 o'clock on the morning of the 11th. There was only one train by which the plaintiff, as he himself testifies, could have reached his wife before her death, and that was the Southern Pacific train which passed Eagle Lake at about 5:35 on the morning of the 11th, and that train reached San Antonio at 11:30 A. M. of that day. Wallis is not on the line of the Southern Pacific road and is 15 miles distant from Eagle Lake. Now, to place the case in the most favorable attitude for the plaintiff, let it be assumed that the telegram was delivered to him at Wallis at 3:20 A. M. of the 11th of January, immediately upon his arrival there. Could he then have procured a conveyance of any kind and reached Eagle Lake in time to have taken the Southern Pacific train passing that point for San Antonio? If he could, and he would have thus been enabled to reach his wife before her death, and there was negligence on the part of the defendant's agents in failing to transmit the message to Wallis, as above defined in this charge, then the plaintiff would be entitled to recover. But if the plaintiff could not have reached Eagle Lake in time for said Southern Pacific train, assuming the telegram to have been delivered at Wallis at 320 A. M. of the 11th, then the plaintiff should not recover in this suit, for, in that case, the injury of which he complains could not have resulted from defendant's negligence, notwithstanding it may not have exercised due diligence in the transmission of the message.

If, in view of the evidence and charge of the court, you find a verdict for the plaintiff, you will award him such sum as will fairly and reasonably compensate him for the disappointment, grief, and mental anguish which he may have suffered on account of his failure to be present with 188his wife before her death. Stuart v. Telegraph, Co., 66 Tex. 580 et seq; Telegraph Co. v. Broesche, 10 S. W. Rep. 736. Under the facts of this case ho exemplary or punitive damages are recoverable.

It is my duty to say to you, in reference to the question of damages, that great caution ought to be observed in the trial of cases like this, as it will be so easy and natural to confound the corroding grief occasioned by the loss of a wife with the disappointment and mental anguish occasioned by the fault or negligence of the company; for it is only the latter for which a recovery may be had So Relle v. Telegraph Co., 55 Tex. 313, 314.

Under the instructions and the evidence, you will render such a verdict, gentlemen, as you may deem right and proper.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.