MCKEY v. VILLAGE OF HYDE PARK.

Circuit Court, N. D. Illinois.

December 17, 1888.

1. BOUNDARIES—BY AGREEMENT—FENCES—ERECTION BY TRESPASSER.

The fact that a trespasser built a fence between two tracts of land will not support an implied agreement between the owners to recognize such fence as a boundary line, where the lands are seldom used by such owners.

2. DEDICATION—BY IMPLICATION.

Where plaintiff knows, on attaining his majority, that a street has been opened and improved across his land, and such street is thereafter maintained and used by the public with his knowledge, and without objection, for seven years or more, a dedication of the land embraced in the street may be inferred by the jury.1

3. SAME—PROVINCE OF JURY.

Where plaintiff resides in another state during the seven years, but his co-tenant resides near the land, and pays the taxes thereon for all the owners, including plaintiff, without objection to the improvement and use of the street; and the street enhances the value of the remaining lands, it is for the jury to say whether plaintiff had knowledge of the street.

4. SAME—PARTITION—APPROVAL BY VILLAGE TRUSTEES—EFFECT.

Approval by village trustees of the report of commissioners in partition proceedings to which the village was not a party, the report partitioning the land occupied by the street, will not restore to plaintiff land previously dedicated by him to the public.

At Law.

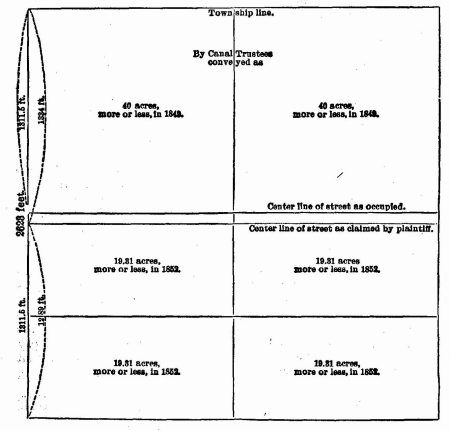

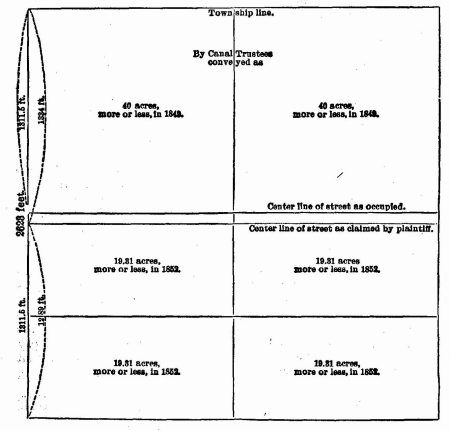

This was an ejectment suit which involved the location of Forty-First street in the village of Hyde Park; the plaintiff claiming that the street, as laid out and occupied by the village, was placed 23 feet too far north; and the case really involved the location of the southern line of the N. W. ¼ of the N. E. ¼ of section 3, township 38 N., range 14 E., and the construction of the United States survey and government descriptions, and conveyances by the canal trustees. The defendant claimed that such southern boundary line was the center line of Forty-First street, as occupied; and the plaintiff claimed that such southern boundary line was 23 feet south of the center line of the street as occupied. Section 3 is in the north tier of the township, and when the government survey was made the shortage was put, as required by law, in the N. ¼of the section, and the N. E. ¼ was surveyed as containing only 157 acres. The whole section was conveyed through the state of Illinois to the canal trustees. In 1849, the canal trustees sold the N. W. ¼and N. E. ¼of the quarter section at the rate of $15 per acre, and issued deeds of conveyance, each in consideration of $600, and describing the property as the quarter of the quarter, containing 40 acres, more or less. In 1852, the canal trustees sold and conveyed the south and north halves, respectively, of the south-east and south-west quarters of the quarter section, as containing 19 and a fraction acres each, more or less, and received pay in each case for that number of acres. The plaintiff here claimed that by these conveyances it was shown that the canal trustees, in conveying 390the “north-west quarter of the north-east quarter” of the section, “containing forty (40) acres, more or less,” intended to and did convey 80-157 of the W. ¼ of the quarter section; that is, the west line of the quarter section being about 2,623 feet long, the N. W. ¼ of the quarter section would extend 80-157 of that distance, or about 1,334 feet, which is 14 feet longer than a full quarter section. The defendant, on the other hand, insisted that the N. W. ¼of the quarter meant the equal half of the W. ½ of the quarter, and that the west line thereof would be just one-half of the west line of the quarter section itself, or one-half of 2,623 feet, which was the basis taken for establishing the center line of Forty-First street at the time it was laid out. Plaintiff also claimed that the line as claimed by him had been recognized and established by former owners by the erection of a fence. Defendant opened the street in 1873, and claimed a common-law dedication of the premises in dispute. Plaintiff admitted a dedication of the south 33 feet of the strip, according to his survey, but claimed defendant had taken 23 feet more. The plat given shows more fully the situation of the quarter section.

N. E. ¼ of Sec 3, 38, 14,—157.24 acres.

Judge Doolittle and Henry McKey, for plaintiff.

James R. Mann and Henry V. Freeman, for defendant.

GRESHAM, J., (charging the jury.) The canal trustees owned the N. E. ¼ of section 3, township 38 N., range 14 E. They conveyed the N. W. ¼ of this N. E. ¼ to P. F. W. Peck, describing it in the deed as the N. W. ¼ of the N. E. ¼ of the section, containing 40 acres, more or less. It is admitted that on June 1, 1866, Edward C. Cleaver held the legal title to this land, and on that day he and his wife by their deed conveyed to Edward and Michael McKey, who were brothers, the south 10 acres of the tract. In 1873 the village of Hyde Park laid out and opened Forty-First street, 66 feet wide, from Grand Boulevard to Vincennes avenue, the center of which was a line equidistant from the north and south lines of the quarter section, on the theory that this was the true east and west boundary between the four quarters of the quarter section, and the true southern boundary of the McKey tract. The street thus laid out appears to have been used by the public without objection from abutting proprietors, until proceedings were commenced in the state court in 1881 for partition of the McKey tract. The decree of partition required the report of the commissioners as to subdivision to be approved by the trustees of the village of Hyde Park, which was done, as appears by the following entry on the plat: “Approved by the president and board of trustees this 8th day of September, 1882. E. W. HENRICKS, Village Clerk.” This plat, thus approved, was made a part of the report of the commissioners, which the state court by its decree confirmed; but the village of Hyde Park was not a party to the suit and was not concluded by it.

Samuel S. Greeley was employed by the commissioners to make the subdivision, and on the plat already referred to certified that it correctly represented the subdivision as he had surveyed and staked it. Instead of taking a line east and west through the center of the quarter section as the true original southern line of the McKey tract, which was indicated by the center of the street, Greeley ran and staked a line 23 feet south of this, thus giving to the McKeys 23 feet of the street; and the partition and subdivision were made on the theory that this survey was correct. The land in dispute is part of this 23 feet, it having been assigned to the plaintiff as part of his share as one of the heirs of Michael McKey, who died in 1868. The plaintiff became of age in 1874, and lived at Janesville, Wis., until a year or two ago, when he removed to Chicago. Greeley gave you his reasons for refusing to recognize the center of the street as the true east and west boundary between the four quarters of the section, and I will not detain you by rehearsing his testimony on that point. You will bear in mind that the McKey 10-acre tract was taken off the south side of the N. W. ¼ of the N. E. ¼, and you are instructed that the canal trustees conveyed to Peck one equal fourth of the quarter section, and that no subsequent conveyances of the trustees had the effect of either enlarging or diminishing that grant; and if you believe from the evidence that the center of the street is the center 392east and west line of the quarter section, then you are also instructed that it was and still is the true boundary line, and that the plaintiff is not entitled to the land described in the declaration, on the theory that the Greeley survey was correct.

But it is contended that, even if the center of the street represents the correct original line, the adjoining proprietors, by agreement, established a boundary line still further south, which was represented by an old board fence. You have heard the evidence touching that fence, and it is for you to say whether it is sufficient to establish such an agreement. We are not informed by whose authority the fence was built, when it was built, or who occupied the lands north and south at the time it was erected. You are to determine, however, what the evidence is upon this point. If the fence was built by a squatter or trespasser, when the lands were of little practical use, and were therefore neglected by the owners, that of itself would not support an implied agreement to treat the fence as a boundary line. The law calls for clear proof in support of an agreement between adjoining proprietors for the establishment of a boundary line different from the true one. I do not say that such an agreement may not be inferred from acts and conduct. For example, if two adjoining proprietors erect or maintain a dividing fence, or hold possession and cultivate land on either side of a fence for a long time, or for-a considerable time, that, of itself, might warrant an implied agreement between them to make the fence the true boundary line; but in this connection you will bear in mind that Mr. Henry McKey, who is one of the children and heirs of Edward McKey, and as such inherited an interest in the McKey tract, testified that from the time the street was laid out, in 1873, until the Greeley survey, he supposed the true boundary line was the center of the street, and that the old fence did not represent the true line. It was not, he said, until Greeley informed him, in connection with the partition proceeding, the McKey heirs owned 23 feet of the street on the north side, that he thought of the old fence as the original boundary line. How far Henry McKey then and prior to that time represented the plaintiff and the other owners, you will determine from the evidence. He certainly had acted as their agent to some extent. It is admitted that he had paid the taxes on the tract, and that he knew of the laying out and improvement of the street. You will weigh all the evidence, and determine whether or not the McKeys, including the plaintiff, who became of age in 1874, knew of the laying out and improvement of the street and its use by the public, without protest or objection, until informed by Greeley that there was a mistake in the location of the south boundary line, and that they owned 23 feet of the street. Mr. Henry McKey testified that he asserted the right of the McKeys to the 23 feet of the street when street assessments were made, and protested against such assessments; but did he do that before Greeley informed him that the McKeys owned part of the street?

If you believe from the evidence that in 1874, when plaintiff attained his majority, he knew of the action of the village of Hyde Park in laying out, opening, and improving the street, and that thereafter and until the 393partition suit was commenced, in 1881 or later, the street was maintained and used with his knowledge, and without objection by him, you are authorized to infer a dedication to that use of so much of the McKey tract as is embraced within the present limits of the street. The owner of land may dedicate it to the public to be used as a street, and, having once done so, he cannot recover the land thus disposed of so Jung as it is used for that particular purpose; and, while there can be no dedication unless it be the intention of the owner to so dispose of his property, an intention to dedicate may be inferred, if, with his knowledge and without objection, his land is improved and used for a number of years as a street. Was this street maintained, improved, and used from the time the plaintiff became of age until the partition suit was commenced, in 1881 or later, without the knowledge of the plaintiff? During this time he resided in a neighboring state, and one of his cotenants, Henry McKey, was a practicing attorney at Chicago, made no objection to the improvement and use of the street, and paid the taxes on the McKey tract for all the owners, including the plaintiff. If it is true, as claimed, that the opening and improvement of this street materially enhanced the value of the McKey lands, and thus greatly benefited the owners of the property, is it probable that during all this time the plaintiff did not know there was such a street? Is it, or not, probable that Henry McKey failed to inform his co-tenants of action so material to their interests, if indeed they needed such information.

If you find that the village of Hyde Park acquired, as against the plaintiff, the right to the strip of land in dispute, for use as a public street, was that right lost by the action of the state court in confirming the report of the commissioners in the partition suit, and the action of the village trustees in approving the plat which was made on the basis of the Greeley survey? I have already stated that the village of Hyde Park was not a party to the partition suit, and that it was not therefore concluded by the decree of the state court; and you are now further instructed that if the plaintiff had dedicated his interest in the strip in dispute for use as a street, subsequent action of the trustees of the village, in connection with the subdivision of the McKey tract, did not have the effect of restoring to the plaintiff what he had disposed of.

Verdict for the defendant.

1 As to what will raise a presumption of dedication of land as a street, see Rube v. Sullivan. (Neb.) 87 N. W. Rep. 666, and note. See, also, City of Eureka v. Croghan, (Cal.) 19 Pac. Rep. 485, and note.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.