THE GILSON et al.

District Court, N. D. New York.

June 8, 1888.

1. COLLISION—TUGS AND TOWS—TOO LARGE TOW—NARROW CHANNEL—LOOKOUTS.

Libelants' scow, loaded with sand, was being towed by the tug Griffin, to libelants' dock on the northerly bank of the Erie canal, in the city of Buffalo, opposite slip No. 3. Immediately beyond the slip the canal Was blocked with boats, rendering navigation in that direction impossible. While the Griffin was endeavoring to land her tow, the tug Gilson, only 37 feet long, with two loaded canal-boats in tow, was coming down the slip, with the current, at about four and one-half miles an hour. While in the slip; and when 175 feet from the Griffin, the Gilson went back to the rear canal-boat, and endeavored to check the tow; but the head canal-boat was carried across the canal, struck the Griffin, and forced her against libelants' scow, causing the latter to sink. Held, 334that the Gilson was clearly in fault—First, in undertaking to tow, with the current, at such speed, two loaded banal-boats through a narrow water-way full of vessels, and where a right-angle turn was necessary; second, in not seeing the position of the Griffin and scow, when she entered the slip 600 feet away. Held, also, that the Griffin wag likewise in fault in not maintaining a watchful lookout for vessels entering the slip.

2. SAME—DAMAGES.

Where the evidence tends to show that libelants' scow was old, decayed, and improperly constructed, and that she sank from a blow which would not have injured a stanch and seaworthy craft, and the libelants have not had a full opportunity to meet this evidence, which would, unexplained, warrant a decree for a moiety, the court will reserve the question of damages and costs until the coming in of the commissioner's report.

In Admiralty. Libel for collision.

George Clinton, for the libelants.

Josiah Cook, for the George D. Gilson.

George S. Potter, for the John B. Griffin.

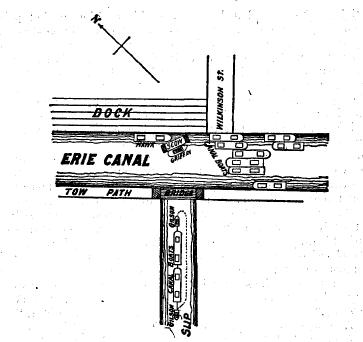

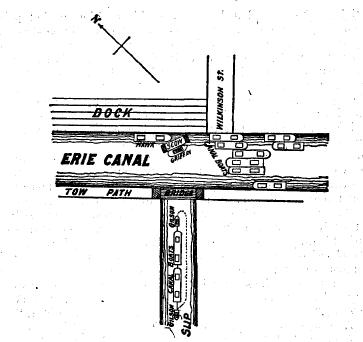

COXE, J. The libelants bring this action against the steam-tugs Gilson and Griffin, to recover damages occasioned by their alleged negligence in causing, a collision by reason of which the Ann Walker, a sand-scow owned by the, libelants, was injured. On the afternoon of May 5, 1887, the scow, loaded with sand, was being towed by the tug Griffin. The tug was lashed to the starboard side of the scow, her stem being five feet aft of the stem of the scow. Their destination was the libelants' dock, on the northerly bank of the Erie Canal, in the city of Buffalo, nearly opposite slip No. 3. The barge Hawk lay moored a little westerly of this point. Immediately beyond the slip, and but a short distance from its entrance, the canal was blocked with boats, rendering navigation in that direction impossible. The tug was endeavoring to make a landing for her tow, and was so engaged for about 10 minutes. During this time the tug Gilson, with two loaded canal-boats in tow, one behind the other, was coming down the slip at about four and one-half miles an hour. While in the slip, and when distant from the Griffin about 175 feet, the Gilson threw off her line, went back to the rear canal-boat, and endeavored to check the progress of the tow. It was then too late. The head canal-boat was carried across the canal, struck the tug Griffin, and forced her against the scow, causing the latter to sink. The current through the slip is towards the canal, and on the day in question was about three miles an hour. The slip, from the canal to the Erie basin, is about 600 or 700 feet in length, and 75 feet wide. The view through it, under the bridges, was, on the day in question, unobstructed. The canal, at the point opposite the slip, is about 150 feet wide. The distance from the bow of the Gilson to the stern of the second canal-boat, including the tow-line was about 240 feet. The Gilson is the smallest tug employed in the harbor of Buffalo, and was built originally for a sail-boat. She is 27 feet long, and 8 feet beam. The Griffin is 64½ feet long, and 13 feet beam. The Walker is 91 feet 10 inches in length, and 19 feet 1 inch beam. The barge Hawk is 108 feet 10 inches long, and 22 feet 3 inches beam. The Situation may be more clearly understood by an examination of the following diagram.

335

The tug Grison was clearly in fault—First. In undertaking to tow with the current, at a relatively high rate of speed, two loaded canal-boats, through a narrow water-way full of stationary and moving vessels, and where a right-angle turn was necessary. She was too small a tug to attempt such a task. Second. In not seeing the position of the Griffin and the Walker when she entered the slip, 600 feet away. If her brew had been on the lookout when she left the Erie basin, she could have controlled her tow, and prevented the accident. When she did discover the situation she was but 175 feet distant from the Griffin. The danger was then imminent. The time was insufficient for any effective measures to secure safety. The space in which to maneuver was inadequate. The Gilson should not have started with two loaded boats on such a journey. Having done so, however, it was her duty to proceed with the utmost care. She took no precautions. Her course throughout was one of extreme recklessness.

It is not easy to perceive how negligence can be imputed to the Gilson without inculpating the Griffin also. If the Gilson should have seen the Griffin, it was equally the duty of the latter to have maintained a watchful lookout. If the master of the Griffin had discovered the Gilson when she first entered the slip, he would have known that there was certain peril for him if he continued in the position he then occupied. He would have known that the Gilson—the smallest tug navigating the harbor—was advancing with two loaded canal-boats; that she intended to swing this disproportionately large tow around a corner where the currents meet 336at right angles; and that, by reason of his position at that point, the channel—at best a narrow one—was reduced to nearly one-half its ordinary width. In short, he would have known that, unless he took some steps to prevent it, a collision was inevitable. There is little reason to doubt that if he had discovered the Gilson when she was 600 feet distant, he could have rescued his own vessel and the scow from their hazardous position. To adopt the language of the brief submitted by the counsel for the Griffin: “The Gilson was engaged in the unheard of proceeding of attempting to tow two loaded canal-boats through the swift current of the slip into a canal crowded with boats. The masters of some of our largest tugs would not have dreamt of doing such a thing with their vessels.” Had the master of the Griffin been on the alert, he must have discovered this obviously heedless proceeding; at least he might have given timely warning of the situation to the Gilson. Knowing, as he might have known, and as he should have known, how impossible it was for the Gilson to proceed in safety with the channel so obstructed, it was clearly his duty to vacate the position which he occupied. He deliberately placed his tug directly across the channel at a dangerous point, in the track of moving vessels, and did ho act to avert disaster. Being in a dangerous place, he should have taken extraordinary means to secure safety. He took no means at all. The situation was not unlike that of The Troy, 28 Fed. Rep. 861. See, also, The B. & C., 18 Fed. Rep. 543; The Morgan, 6 Fed. Rep. 200; The Titan, 23 Fed. Rep. 413; Wells v. Armstrong, 29 Fed. Rep. 216; The Vigus, 22 Fed. Rep. 747.

The evidence tends to show that the scow Walker was old, decayed, and improperly constructed, and that she sank from a blow that would not have injured a stanch and seaworthy craft. The libelants did not have a full opportunity to meet this testimony, and, as in all probability it will affect the question of damages alone, they have requested that the consideration of this branch of the controversy be postponed until the coming in of the commissioner's report. No rights can be jeoparded by granting this request. If the evidence now before the court remains unexplained, the court may see fit to limit the decree to a moiety of the damages. The Syracuse, 18 Fed. Rep. 828; The N. B. Starbuck, 29 Fed. Rep. 797; The City of Augusta, 30 Fed. Rep. 844. In other respects the Walker seems, to be free from fault. It cannot be said that it was negligence to make a landing at the point in question.

There should be a decree against the two tugs, and a reference to compute the damages. The question of costs may be reserved until the coming in of the commissioner's report.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.