730

STATE OF ILLINOIS v. ILLINOIS CENT. R. CO. CITY OF CHICAGO v.

SAME. UNITED STATES v. SAME.

Circuit Court, N. D. Illinois.

February 23, 1888.

v.33F, no.14-47

v.33F, no.14-48

v.33F, no.14-49

1. PUBLIC LANDS—MILITARY SITES—SALE—ACT OF MARCH 3, 1819—DELEGATION OF POWER.

Under act Cong. March 3, 1819, authorizing the secretary of war to cause to be sold certain military sites, such sale could be made through an agent specially appointed for that purpose, and acting under a power of attorney.

2. SAME—SUBDIVISION INTO BLOCKS AND LOTS.

And if In making a sale, under such act, of lands within the limits of, or near to, a municipal corporation, a subdivision of the tract into blocks, lots, and streets would be most beneficial to the government, it was the duty of the secretary of war to adopt that method of selling the tract.

3. SAME—DEDICATION—TITLE TO STREETS.

When Fort Dearborn reservation, near the mouth of Chicago river, was subdivided by the agent of the secretary of war, proceeding under the act of congress of March 3, 1819, into lots, and they were sold with reference to the map or plat of such subdivision, and it was no longer used as a military site or for any purpose connected with the exercise of the powers of the general government, all the lands embraced within its limits ceased to be a part of the national domain. The title to the specific lots passed to those who purchased them, while jurisdiction over the streets and open grounds dedicated to public use passed from the United States; the title to, and immediate possession and control of, such streets and grounds vesting in the local government—that is in the municipal corporation of Chicago—as a public agency of the state for the purposes for which such dedication was made.

4. RIPARIAN RIGHTS—MUNICIPAL CORPORATIONS—POWERS—DELEGATION TO RAILROAD.

The city of Chicago, as riparian owner of ground on the shore of Lake Michigan, having, by the provisions of its charter, to maintain wharves and slips at the end of streets, and to maintain a breakwater to protect the shore from the encroachment of the lake, could delegate the power to erect such breakwater to a railroad company as consideration for allowing the road to enter the city; and upon the erection of such breakwater, and the filling in of the space between the breakwater and the shore-line the land thus reclaimed belongs to the city. BLODGETT, J., dissenting.

5. SAME.

In the absence of any legislative or governmental direction as to the manner of the occupancy of the bed of Lake Michigan within the state of Illinois, the Illinois Central Railroad Company, as the riparian owner of the water-lots in the city of Chicago north of Randolph street, and south of Park row, had the right, by virtue of such ownership, and as part of its purchase of such lots to connect the shore-line by artificial constructions with outside waters that were navigable in fact; although the exercise of that right is at all times subject to such regulations—at least, those not amounting to prohibition—as the state may establish.

6. SAME—POWER OF STATE OVER RIPARIAN OWNERS.

The state of Illinois has the power, by legislation, to prescribe the lines in the harbor of Chicago beyond which piers, docks, wharves, and other structures—other than those erected under the authority, express or implied, of the general government—may not be built by riparian owners in the waters of the harbor that are navigable in fact.

7. SAME—RAILROAD COMPANIES—CHARTERS AND FRANCHISES.

The charter of the Illinois Central Railroad Company granted it the right to take and use all such lands and waters belonging to the state as were necessary to the construction and complete operation of the road, provided such use did not interrupt navigation of the waters. Held that, upon the consent from the city of Chicago to enter its limits, the company had the right to erect piers and breakwaters, and fill in the shallow waters of Lake Michigan within 731such city limits and use the ground thus made for its road-bed and other purposes, provided such piers and breakwaters did not interrupt the navigation of the lake.

8. STATUTES—ENACTMENT—FAILURE OF JOURNAL TO SHOW COMPLIANCE WITH CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISION.

Under the provision of Const. Ill. 1848, art. 3, § 23, that all legislative acts must be read on three different days in each house, it is not necessary to the validity of an act that the journal of either house should show affirmatively that such act was read three times.

9. SAME—AMENDMENT OF TITLE.

Where the original title of an act upon its introduction into the legislature contained superfluous words, and after its passage the title was changed to express truly the subject of the act, such superfluity in the original title will not affect the validity of the act.

10. CONSTITUTIONAL LAW—LOCAL AND SPECIAL LAWS.

An act public in its nature, and in which the people of the whole state have an interest, but which specially concerns the property and rights of a portion of the people of the state, is a local act, within the meaning of Const. Ill. 1848, art. 3, § 23, relating to the title of private or local acts.

11. SAME—TITLES OF LAWS.

Act Ill. April 16, 1869, entitled “An act in relation to a portion of the submerged lands and Lake Park grounds lying on and adjacent to the shore of Lake Michigan on the eastern frontage of the city of Chicago,” contained provisions giving the city the fee to certain partially submerged lands, with authority to sell; also provisions giving the fee to certain other submerged lands to a railroad company, with the right to maintain docks and Wharves. Held that, the general subject of the act being the disposal of lands on and adjacent to the shore of Lake Michigan on the eastern frontage of Chicago, the subject was sufficiently expressed in the title, within the meaning of Const. Ill. 1848, art. 3; § 23, providing that all local laws must contain but one subject which must be expressed in the title.

12. SAME—LEGISLATIVE GRANTS—SEAL OF STATE.

The provisions of Const. Ill. 1848, art. 4, § 25, that all grants shall be sealed with the great seal of the state, signed by the governor, and countersigned by the secretary of state, do not operate to render void a grant of lands by legislative enactment.

13. SAME—CORPORATIONS—CREATION BY SPECIAL LAW—GRANT OF SPECIAL PRIVILEGE TO EXISTING CORPORATION.

Const. Ill. 1870, art. 11, §§ 1, 2, provide that no corporation shall be created, or its power enlarged, by special laws, and that all the existing charters or grants of special or exclusive privileges under which organization shall not have taken place, or which shall not have been in operation within 10 days of the time the constitution took effect, should have no validity. Held, that the sections cited referred only to corporations which were then unorganized, or were not in operation as corporations, and should not be construed to take away any special or exclusive privileges granted to corporations organized and in actual operation.

14. SAME—REPEALING OBLIGATION TO PAY MONEY INTO TREASURY.

Act Ill. April 16, 1869, granted to the defendant railroad certain submerged lands, upon condition that defendant pay into the state treasury a per centum of the gross earnings of the road. Held, that act Ill. April 15, 1873, repealing such grant, is not repugnant to the separate section of the constitution of Illinois providing that no contract, obligation or liability of defendant to pay money into the state treasury, nor any lien of the state upon, or right to tax the property of, defendant, under the defendant's charter of 1851, shall be released, suspended, diminished, or impaired.

15. SAME—CONFIRMATION OF TITLE—PRIOR ACTS—REVOCATION.

Act Ill. April 16, 1869, confirmed the right of defendant railroad company, under the grant in its charter, and under and by virtue of its appropriation, occupancy, use, and control, and the riparian ownership incident thereto, in and to certain lands. Held, that the confirmation, covering all that had been done by defendant in relation to such lands prior to the date of the act, was equivalent to an original authority so to do, and such confirmation could not be revoked by subsequent enactment.

732

16. PUBLIC LANDS—GRANT BY STATE—CONSTRUCTION OF GRANT.

Act Ill. April 16, 1869, granted to the defendant certain submerged lands in the harbor of Chicago in fee, with a proviso that defendant should not have power to alienate such lands, and that the gross receipts from the use, profits, and lease of the lands, or improvements thereon should be a part of the gross receipts of the company for the purposes of taxation. It was also provided that the harbor should not be obstructed, or the right of navigation impaired, and that the legislature might regulate the rates of wharfage and dockage. Held, that the grant was in trust only, with the additional privilege to make certain improvements in the harbor, and was revocable, except as to such lands as, at the time of the repeal thereof, had already been improved and reclaimed, upon the faith of the grant.

17. SAME—PERFORMANCE OF CONDITIONS—TENDER—FAILURE TO KEEP TENDER GOOD.

Act Ill. April 16, 1869, granted defendant certain lands in fee, upon payment of a certain sum to the city within the limits of which the land was situate. A tender of the money was made, but the city refused to receive it. Held, that a failure to keep the tender good deprived the defendants of all rights acquired thereunder.

In Equity.

W. G. Ewing, Dist. Atty., for the United States.

George Hunt, Atty. Gen., E. B. McCagg, and Williams & Thompson, for the People.

B. F. Ayer, J. N. Jewett, and Lyman Trumbull, for Illinois Cent. R. Co.

James K. Edsall and A. S. Bradley, for Citizens' Committee.

M. W. Fuller, for City of Chicago.

Before HARLAN, Circuit Justice, and BLODGETT, District Judge.

HARLAN, Justice.The first of the above-named causes is a suit in equity in the name of the people of the state of Illinois against the Illinois Central Railroad Company, the city of Chicago, and the United States of America. It was commenced in the circuit court of Cook county, Illinois, and subsequently, on the petition of the railroad company, was removed into this court. A motion to remand the cause was denied, upon grounds indicated in State v. Railroad Co., 16 Fed. Rep. 881. The railroad company and the city filed answers, and the latter also filed a crossbill for affirmative relief against the state and its co-defendants. To that cross-bill the company filed an answer, as did also the attorney general of Illinois in behalf of the state. The United States has not appeared, either in the original or cross suit. This cause may be regarded as under submission for final decree as between the state, the railroad company, and the city in the original suit; also as between the city and the railroad company in the cross-suit. Notwithstanding the appearance in the cross-suit of the attorney general of Illinois in behalf of the state, some question is made as to the jurisdiction of the court to give to the city any affirmative relief against the state. But that question need not be decided, since all the issues between the state and the city can be finally determined in the original suit brought by the state. The last named of the causes is an information in equity by the United States against the Illinois Central Railroad Company; the Michigan Central Railroad Company, the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company, the Baltimore & Ohio Railroad Company, and the city of Chicago. 733That case is now before us upon demurrer by the two first-named companies to the information.

The general object of these suits is to obtain a judicial determination of the rights of the parties in respect to certain lands on the east or lake front of the city of Chicago, south of Chicago river, upon some of which are tracks, depots, warehouses, piers, and other structures erected by the Illinois Central Railroad Company; and also in respect to the submerged lands within the limits of the city of Chicago, and of the state of Illinois, “constituting the bed of Lake Michigan, and lying east of the tracks and breakwater” of that company, “for the distance of one mile, and between the south line of the south pier [near Chicago river] extended east-wardly, and a line extended eastward from the south line of lot 21, south of and near the round-house and machine-shops of said company.” The cases, besides, involve an inquiry as to the right of the railroad company, for the promotion as well of its own business as of commerce and navigation generally, to erect and maintain wharves, piers, and docks in the harbor of Chicago. Some of these lands were formerly a part of what was known as “Fort Dearborn Military Post,” or the S. W. ¼ of fractional section 10, near the mouth of Chicago river; others, a part of fractional section 15; while others are in section 22,—all of said sections being in township 39 N., range 14 E. of the third P. M., and on the shore of Lake Michigan, in the order named. It is necessary to a clear understanding of the numerous questions presented for determination that we should first trace the history of the title to these several bodies of lands up to the time when the Illinois Central Railroad was located within the limits of Chicago.

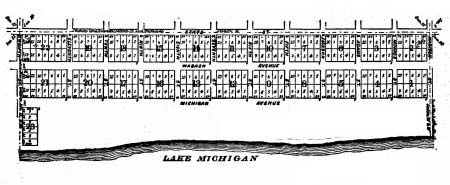

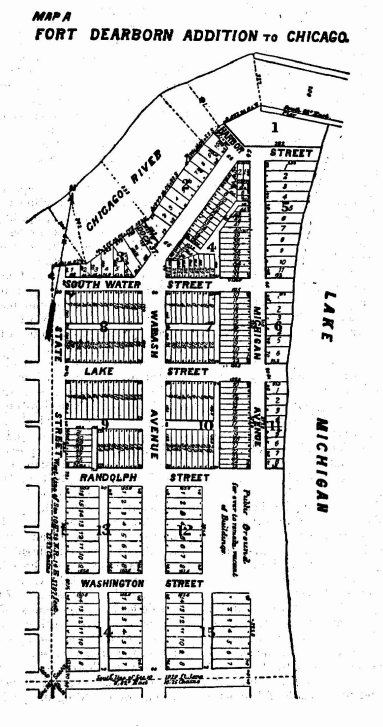

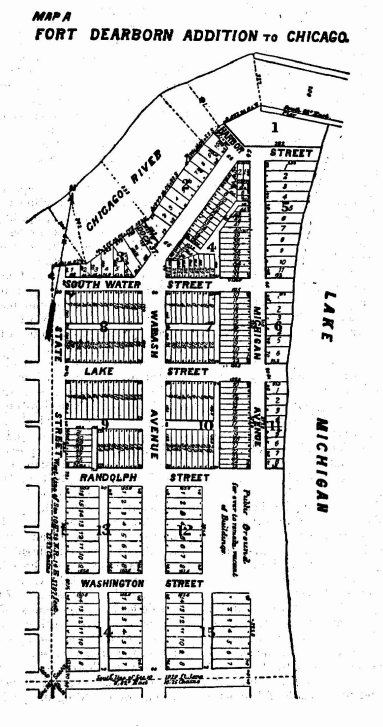

1. As to the Lands Embraced in the Fort Dearborn Reservation. In the year 1804, the United States established the military post of Fort Dearborn, immediately south of Chicago river, and near its mouth, upon the S. W. fractional ¼ of section 10. It was occupied by troops, as well when Illinois, in 1818, was admitted into the Union, as when congress passed the act of March 3, 1819, authorizing the sale of certain military sites. By that act it was provided “that the secretary of war be, and he is hereby, authorized, under the direction of the president of the United States, to cause to be sold such military sites, belonging to the United States, as may have been found or become useless for military purposes. And the secretary of war is hereby authorized, on the payment of the consideration agreed for into the treasury of the United States, to make, execute, and deliver all needful instruments conveying and transferring the same in fee; and the jurisdiction which had been specially ceded, for military purposes, to the United States by a state, over such site or sites, shall thereafter cease.” 3 St. 520. In 1824, upon the written request of the secretary of war, the S. W. ¼ of fractional section 10, containing about 57 acres, and within which Fort Dearborn was situated, was formally reserved by the commissioner of the general land-office from sale, and for military purposes. Wilcox v. Jackson, 13 Pet. 499, 452. The United States admit, and it is also proved, that the lands so reserved were subdivided in 1837, by authority of the secretary,—he being represented 734by one Matthew Birchard, as special agent and attorney for that purpose,—into blocks, lots, streets, and public grounds, called the “Fort Dearborn Addition to Chicago.” And on the 7th day of June, 1839, a map or plat of that addition was acknowledged by Birchard as such agent and attorney, and was recorded in the proper local office. A part of the ground embraced in that subdivision was marked on the recorded plat, “Public ground, forever to remain vacant of buildings.” The plat of that subdivision, called “Map A,” is reproduced, and in the margin will be found the certificates which appear on the plat as made and recorded.1

The lots designated on this plat were sold and conveyed by the United States to different purchasers. The sale and conveyance (to use the words of the information filed by the United States) was “by and according to the said plat, and with reference to the same.” But it should be stated that at the time of the first sales, the United States expressly reserved from sale all of the Fort Dearborn addition (including the ground marked for streets) north of the south line of lot 8 in block 2, lots 4 and 735 7369 in block 4, and lot 5 in block 5, projecting said lines across the adjacent streets. The grounds go specially reserved remained in the occupancy of the general government for military purposes from 1839 until after 1845. The legal effect of that occupancy appears in U. S. v. Chicago, 7 How. 185. The city of Chicago having proposed, in 1844, to open Michigan avenue through the lands so reserved from sale, notwithstanding, at the time, they were in actual use for military purposes, the United States instituted a suit inequity to restrain the city from so doing. It appeared in the case that the agent of the general government gave notice, at the time of selling the other lots, that the ground in actual use by the United States was not then to be sold. It also appeared that the act of March 4, 1837, incorporating the city of Chicago, and designating the district of country embraced within its limits, expressly excepted “the south-west fractional quarter of section 10, occupied as a military post, until the same shall become private property.” Laws Ill. 1837, pp. 38, 74. The court held that the city had no right to open streets through that part of the ground which, although laid out in lots and streets, had not been sold by the government; that its corporate powers were limited to the part which, by sale, had become private property; and that the streets laid out and dedicated to public use by Birchard, the agent of the secretary of war, did not, merely by his surveying the land into lots and streets, and, making and recording a map or plat thereof, convey the legal estate in such streets to the city, and thereby authorize it to open them for public use, and assume full municipal control thereof. The court held to be untenable the claim of the city that “because streets had been laid down on the plan by the agent, [Birchard,] part of which extended into the land not sold, those parts had, by this alone, become dedicated as highways, and the United States had become estopped to object.” Further: “It is entirely unsupported by principle or precedent that an agent, merely by protracting on the plan those streets into the reserved line, and amidst lands not sold, nor meant then to be sold, but expressly reserved, could deprive the United States of its title to real estate, and to its important public works.” See, also, Irwin v. Dixin, 9 How. 31.

7369 in block 4, and lot 5 in block 5, projecting said lines across the adjacent streets. The grounds go specially reserved remained in the occupancy of the general government for military purposes from 1839 until after 1845. The legal effect of that occupancy appears in U. S. v. Chicago, 7 How. 185. The city of Chicago having proposed, in 1844, to open Michigan avenue through the lands so reserved from sale, notwithstanding, at the time, they were in actual use for military purposes, the United States instituted a suit inequity to restrain the city from so doing. It appeared in the case that the agent of the general government gave notice, at the time of selling the other lots, that the ground in actual use by the United States was not then to be sold. It also appeared that the act of March 4, 1837, incorporating the city of Chicago, and designating the district of country embraced within its limits, expressly excepted “the south-west fractional quarter of section 10, occupied as a military post, until the same shall become private property.” Laws Ill. 1837, pp. 38, 74. The court held that the city had no right to open streets through that part of the ground which, although laid out in lots and streets, had not been sold by the government; that its corporate powers were limited to the part which, by sale, had become private property; and that the streets laid out and dedicated to public use by Birchard, the agent of the secretary of war, did not, merely by his surveying the land into lots and streets, and, making and recording a map or plat thereof, convey the legal estate in such streets to the city, and thereby authorize it to open them for public use, and assume full municipal control thereof. The court held to be untenable the claim of the city that “because streets had been laid down on the plan by the agent, [Birchard,] part of which extended into the land not sold, those parts had, by this alone, become dedicated as highways, and the United States had become estopped to object.” Further: “It is entirely unsupported by principle or precedent that an agent, merely by protracting on the plan those streets into the reserved line, and amidst lands not sold, nor meant then to be sold, but expressly reserved, could deprive the United States of its title to real estate, and to its important public works.” See, also, Irwin v. Dixin, 9 How. 31.

2. As to the Lands in Controversy Embraced in Fractional Section 15. This section is on the lake shore, immediately south of section 10. The particular lands, the history of the title to which is to be now examined, are between the west line of the street now known as “Michigan Avenue” and the roadway or way-ground of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, and between the middle line of Madison street and the middle line of Twelfth street, excluding what is known as “Park Row,” or block 23, north of Twelfth street. By an act of the Illinois legislature of February 14, 1823, entitled “An act to provide for the improvement of the internal navigation of this state,” certain persons were constituted commissioners to devise and report upon measures for connecting, by means of a canal and locks, the navigable waters of the Illinois river and Lake Michigan. Laws Ill. 1823, p. 151. This was followed by an act of congress, approved March 2, 1827, entitled “An act to grant a quantity of land to the state of Illinois, for the purpose of aiding in opening a 737canal to connect the waters of the Illinois river with those of Lake Michigan,” granting to this state, for the purposes of such enterprise, a quantity of land, equal to one-half of five sections in width, on each side of the proposed canal, (reserving each alternate section to the United States,) to be selected by the commissioner of the general land-office, under direction of the president; said lands to be “subject to the disposal of the said state for the purpose aforesaid, and for no other;” and said canal to remain forever a public highway for the use of the national government, free from any charge for any property of the United States passing through it. 4 St. 234, c. 51. The power of the state to dispose of these lands was further recognized or conferred by the third section of the act, as follows: “Sec. 3. That the said state, under the authority of the legislature thereof, after the selection shall have been so made, shall have power to sell and convey the whole or any part of the said land, and to give a title in fee-simple therefor to whomsoever shall purchase the whole or any part thereof.” 4 St. 234. By an act of the Illinois legislature of January 22, 1829, entitled “An act to provide for constructing the Illinois and Michigan canal,” the commissioners for whose appointment that act made provision were directed to select, in conjunction with the commissioner of the general land-office, the alternate sections of land granted by the act of congress; such commissioners being invested with the power, among others, “to lay off such parts of said donation into town lots as they may think proper, and to sell the same at public sale in the same manner as is provided in this act for the sale of other lands.” Laws Ill. 1829. The act of 1829 was amended February 15, 1831, so as to constitute the canal commissioners a board, to be known as the “Board of Canal Commissioners of the Illinois and Michigan Canal,” with authority to contract and be contracted with, sue and be sued, plead and be impleaded, and with power of control in all matters relating to said canal. Laws Ill. 1830-31, p. 39. Pursuant to and in conformity with said acts of congress and of the legislature of Illinois, the selection of lands for the purposes specified was made by the proper authorities, and approved by the president on the 21st of May, 1830. Among the lands so selected was said fractional section 15. By an act of the Illinois legislature, approved January 9, 1836, entitled “An act for the construction of the Illinois and Michigan canal,” the governor was empowered to negotiate a loan of not exceeding $500,000, on the credit and faith of the state, as therein provided, for the purpose of aiding, in connection with such means as might be received from the United States, in the construction of the Illinois and Michigan canal, for which loan should be issued certificates of stock, to be called the “Illinois and Michigan Canal Stock,” signed by the auditor, and countersigned by the treasurer, bearing an interest not exceeding 6 per cent., payable semi-annually, and “reimbursable” at the pleasure of the state at anytime after 1860; and for the payment of which, principal and interest, the faith of the state was irrevocably pledged. The same act provided for the appointment of three commissioners, to constitute a board to be known as “The Board of Commissioners of the Illinois and Michigan Canal,” and to be a body politic 738and corporate, with power to contract and be contracted with, sue and be sued; plead and be impleaded, in all matters and things relating to them as canal companies, and to have the immediate care and superintendence of the canal, and all matters relating thereto. Laws Ill. 1836, p. 145. That act contained, among other provisions, the following:

“Sec. 32. The commissioners shall examine the whole canal route, and select such places thereon as may be eligible for town-sites, and cause the same to be laid off, into town lots, and they shall cause the canal lands in or near Chicago, suitable therefor, to be laid off into town lots.

“Sec. 33. And the said board of canal commissioners shall, on the 20th day of June next, proceed to Sell the lots in the town of Chicago, and such parts of the lots in the town of Ottowa, as also fractional section fifteen adjoining the town, of Chicago, it being first laid off and subdivided into town lots, streets, and alleys, as in their best judgment will best promote the interest of the said canal fund: provided, always, that, before any of the aforesaid town lots shall be offered for sale, public notice of such sale shall have been given. * * *” Laws Ill. 1836, p. 149.

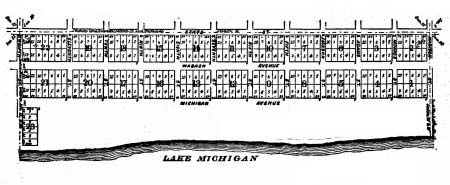

The revenue arising from the canal, and from any lands granted by the United States to the state for its construction, together with the net tolls thereof, were pledged by the act for the payment of the interest accruing on the said stock, and for the reimbursement of the principal of the same. Laws Ill. 1836, p. 153. In 1886, the canal commissioners, under the authority conferred upon them by the statutes above recited, caused fractional section 15 to be subdivided into lots, blocks, streets, etc., a map whereof was made, acknowledged, and recorded on the 20th of July, 1836. A map (the official certificates as they appear on the original map as recorded being in the margin1) is reproduced as “Map B.”

It is proper to say that upon some of the maps in evidence, and duly certified, the words “Michigan Avenue “are nearer to the shore-line than they appear to be on may B. This fact tends to show that the entire space between the shore-line and the lots into which fractional section 15 was subdivided was originally intended as an avenue, or public grounds or commons. At the time this map was made and recorded, fractional

739

MAP

OF

Fractional Section No. Fifteen, Tp. 39 North, Range 14 East of the Third Principal Meridian. Surveyed and Subdivided by the Board of Canal Commissioners, pursuant to Laws, in the Month of April, A. D. 1836.

740 sections 15 and 10 were both within the limits of the “town” of Chicago, except that by the act of February 11, 1835, changing the corporate powers of that town, it was provided “that the authority of the board of trustees of the said town of Chicago shall not extend over the south fractional section 10 until the same shall cease to be occupied by the United States.” Laws Ill. 1835, p. 204. But prior to the survey and recording of the plat of fractional section 10, to-wit, by the act of March 4, 1837, the city of Chicago was incorporated, and its limits defined, (excluding, as we have seen, “the south-west fractional quarter of section 10, occupied as a military post, until the same shall become private property,”) and was invested with all the estate, real and personal, belonging to or held in trust by the trustees of the town; its common council being empowered to lay out, make, and assess streets, alleys, lanes, and highways in said city, to make wharves and slips at the end of the streets, on property belonging to said city, and to alter, widen, straighten, and discontinue the same. Laws Ill. 1837, p. 61, § 38; Id. p. 74, § 61.

740 sections 15 and 10 were both within the limits of the “town” of Chicago, except that by the act of February 11, 1835, changing the corporate powers of that town, it was provided “that the authority of the board of trustees of the said town of Chicago shall not extend over the south fractional section 10 until the same shall cease to be occupied by the United States.” Laws Ill. 1835, p. 204. But prior to the survey and recording of the plat of fractional section 10, to-wit, by the act of March 4, 1837, the city of Chicago was incorporated, and its limits defined, (excluding, as we have seen, “the south-west fractional quarter of section 10, occupied as a military post, until the same shall become private property,”) and was invested with all the estate, real and personal, belonging to or held in trust by the trustees of the town; its common council being empowered to lay out, make, and assess streets, alleys, lanes, and highways in said city, to make wharves and slips at the end of the streets, on property belonging to said city, and to alter, widen, straighten, and discontinue the same. Laws Ill. 1837, p. 61, § 38; Id. p. 74, § 61.

This brings us, in the chronological order of events relating to this litigation, to the incorporation of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, and the location of its road within the limits of the city of Chicago. Congress having, by an act approved September 20, 1850, (9 St. 466, c. 61,) made a grant of land to Illinois for the purpose of aiding the construction of a railroad from the southern terminus of the Illinois & Michigan canal to a point at or near the junction of the Ohio and Mississippi rivers, with branches to Chicago and Dubuque, the Illinois Central railroad Company was incorporated February 10, 1851, and made the agent of the state to construct that road. Priv. Laws Ill. 1851, p. 61. It was granted power by its charter “to survey, locate, construct, complete, alter, maintain, and operate a railroad, with one or more tracks or lines of rails, from the southern terminus of the Illinois and Michigan canal to a point at the city of Cairo, with a branch of the same to the city of Chicago, on Lake Michigan; and also a branch, via the City of Galena, 741to a point on the Mississippi river opposite the town of Dubuque, in the state of Iowa.” In addition to certain powers, privileges, immunities, and franchises,—including the right to purchase, hold, and convey real and personal estate, which might be needful to carry into effect the purposes and objects of its charter,—it was provided that the company “shall have the right of way upon, and may appropriate to its sole use and control, for the purposes contemplated herein, land not exceeding two hundred feet in width through its entire length; may enter upon, and take possession of, and use, all and singular, any lands, streams, and materials of every kind for the location of depots and stopping stages, for the purposes of constructing bridges, dams, embankments, excavations, station grounds, spoil banks, turn-outs, engine-houses, shops, and other buildings necessary for the construction, completing, altering, maintaining, preserving, and complete operation of said road. All such lands, waters, materials, and privileges belonging to the state are hereby granted to said corporation for said purposes: * * * provided, that nothing in this section contained shall be so construed as to authorize the said corporation to interrupt the navigation of said streams.” Section 3. But the company's charter also provided, (section 8:) “Nothing in this act contained shall authorize said corporation to make a location of their tract within any city without the consent of the common council of said city.”

Such consent was given by an ordinance of the common council of Chicago, adopted June 14, 1852, whereby permission was granted to the company to lay down, construct, and maintain within the limits of that city, and along the margin of the lake within and adjacent to the same, a railroad with one or more tracks, and to have the right of way and all powers incident to and necessary therefor, upon certain terms and conditions, to-wit: “The said road shall enter at or near the intersection of its southern boundary with Lake Michigan, and following the shore on or near the margin of said lake northerly to the southern bounds of the open space known as ‘Lake Park,’ in front of canal section fifteen, and continue northerly across the open space in front of said section fifteen, to such grounds as the said company may acquire between the north line of Randolph street and the Chicago river, in the Fort Dearborn addition in said city; upon which said grounds shall be located the depot of said railroad within the city, and such other buildings, slips, or apparatus as may be necessary and convenient for the business of said company. But it is expressly understood that the city of Chicago does not undertake to obtain for said company any right of way, or other right, privilege, or easement, not now in the power of said city to grant or confer, or to assume any liability or responsibility for the acts of said company.” Section 1. By other sections of the ordinance it was provided as follows: By the second section, that the company might “enter upon and use in perpetuity for its said line of road, and other works necessary to protect the same from the lake, a width of 300 feet, from the southern boundary of said public ground near Twelfth street to the northern line of Randolph street; the inner or west line of the ground to be used by said company to be not less than 400 feet east from the west line of Michigan avenue and parallel 742thereto.” By the third section, that they “may extend their works and fill out into the lake to a point in the southern pier not less than 400 feet west from the present east end of the same, thence parallel with Michigan avenue to the north, line of Randolph street extended; but it is expressly understood that the common council does not grant any right or privilege beyond the limits above specified, nor beyond the line that may be actually occupied by the works of said company.” By the sixth section, that the company “shall erect and maintain on the western or inner line of the ground pointed out for its main track on the lake shore, as the same is hereinbefore defined, such suitable walls, fences, or other sufficient works as will prevent animals from straying upon or obstructing its tracks, and secure persons and property from danger; said structure to be of suitable materials and sightly appearance, and of such heights as the common council may direct, and no change thereon shall be made except by mutual consent: provided, that the company shall construct such suitable gates at proper places at the ends of the streets, which are now or may hereafter be laid out, as may be required by the common council, to afford safe access to the lake: and provided, also, that incase of the construction of an outside harbor, streets may be laid out to approach the same, in the manner provided by law; in which case the common council may regulate the speed of locomotives and trains across them.” By the seventh section, that the company “shall erect and complete within three years after they shall have accepted this ordinance, and shall forever thereafter maintain, a continuous wall or structure of stone masonry, pier-work, or other sufficient material, of regular and sightly appearance, and not to exceed in height the general level of Michigan avenue opposite thereto, from the north side of Randolph street to the southern bound of Lake park before mentioned, at a distance of not more than 300 feet east from and parallel with the western or inner line, pointed out for said company, as specified in section two hereof, and shall continue said works, to the southern boundary of the city, at such distance outside of the track of said road as may be expedient; which structure and works shall be of sufficient strength and magnitude to protect the entire front of said city, between the north line of Randolph street and its southern boundary, from further damage or injury from the action of the waters of Lake Michigan; and that part of the structure south of Lake park shall be commenced and prosecuted with all reasonable dispatch after acceptance of this ordinance.” By the eighth section, that the company “shall not in any manner, nor for any purpose whatever, occupy, use, or intrude upon the open ground known as ‘Lake Park,’ belonging to the city of Chicago, lying between Michigan avenue and the western or inner line before mentioned, except so far as the common council may consent, for the convenience of said company, while constructing or repairing the works in front of said ground.” By the ninth section, that the company “shall erect no buildings between the north line of Randolph street and the south line of the said Lake park, nor occupy nor use the works proposed to be constructed between these points, except for the passage of or for making up or distributing their trains, 743nor place upon any part of their works between said points any obstruction to the view of the lake from the shore, nor suffer their locomotives, cars, or other articles to remain upon their tracks, but only erect such works as are proper for the construction of their necessary tracks, and protection of the same.” The company was given 90 days within which to accept the ordinance, and it was provided that, upon such acceptance, its terms should be embodied in a contract between the city and the company. The ordinance was accepted, and the required agreement entered into, on the 8th day of July, 1852.

At the time this ordinance was passed, the harbor of the city included, under the laws of the state incorporating the city, “the piers, and so much of Lake Michigan as lies within the distance of one mile thereof into the lake, and the Chicago river and its branches to their respective sources.” Laws Ill. 2d Sess. 1849 and 1851, pp. 132, 147. Its common council had power, at the public expense, to construct a breakwater or barrier along the shore of the lake for the protection of the city against the encroachments of the water; “to preserve the harbor; to prevent any use of the same, or any act in relation thereto, * * *; tending in any degree to fill up or obstruct the same; to prevent and punish the casting or depositing therein any earths, ashes, or other substance, filth, logs, or floating matter; to prevent and remove all obstructions therein, and to punish the authors thereof; to regulate and prescribe the mode and speed of entering and leaving the harbor, and of coming to and departing from the wharves and streets of the city by steam-boats, canal-boats, and other crafts and vessels; * * * and to regulate and prescribe by such ordinances, or through their harbor-master, or other authorized officer, such a location of every canal-boat, steam-boat, or other craft or vessel or float, and such changes of station in and use of the harbor, as may be necessary to promote order therein, and the safety and equal convenience, as near as may be, of all such boats, vessels, crafts, or floats;” “to remove and prevent all obstructions in the waters which are public highways in said city, and to widen, straighten, and deepen the same;” and to “make wharves and slips at the end of streets, and alter, widen, contract, straighten, and discontinue the same.” Id.

Under the authority of its charter, and of the ordinance of June 14, 1852, the railroad company located its tracks within the corporate limits of the city. The tracks northward from Twelfth street were laid upon piling placed in the waters of the lake,—the shore-line, which was crooked, being, at that time, at Park row, about 400 feet from the west line of Michigan avenue; at the foot of Monroe and Madison streets, about 90 feet; and at Randolph street, about 112½ feet. Since that time the space between the shore-line and the tracks of the railroad company has been filled with earth by or under the direction of the city, and is now solid ground. After the construction of the track as just stated, the railroad company erected a breakwater east of its roadway, upon a line parallel with the west line of Michigan avenue, and subsequently filled the space, or nearly all of it, between that breakwater and its tracks, and under its tracks, with earth and stone. 744 It is stated by counsel, and the record, we think, sufficiently shows, that when the road was located in 1852 nearly all of the lots bordering upon the lake north of Randolph street had become the property of individuals, by purchase from the United States, except a parcel adjacent to the river which had not then been sold by the general government. Soon thereafter the company acquired the title to all of the water lots in the Fort Dearborn addition north of Randolph street, including the remaining parcel belonging to the United States. The deed for the latter was made by the secretary of war, October 14, 1852, and included “all the accretions made, or to be made, by said lake and river in front of the land hereby conveyed, and all other rights and privileges appertaining to the United States as owners of said land.” The company established its passenger-house at the place designated in the ordinance of 1852, and, being the owner of said water lots north of Randolph street, it gradually pushed its works out into the shallow water of the lake to the exterior line specified in that ordinance, 1,376 feet east of the west line of Michigan avenue. In order that the railroad company might approach its passenger depot, the common council, by ordinance adopted September 10, 1855, granted it permission to curve its tracks westwardly of the line fixed by the ordinance of 1852, “so as to cross said line at a point not more than 200 feet south of Randolph street, extending and curving said tracks north-westerly as they approach the depot, and crossing the north line of Randolph street extended at a point not more than 100 feet west of the line fixed by the ordinance, in accordance with the map or plat thereof submitted by said company, and placed on file for reference.” This grant was, however, upon the following conditions: That the company lay out upon its own land, west of and alongside its passenger-house, a street 50 feet wide, extending from Water street to Randolph street, and fill the same up its entire length within two years from the passage of said ordinance; that it should be restricted in the use of its tracks south of the north line of Randolph street, as provided in the ordinance of 1852; and “when the company shall fill up its said tracks south of the north line of that street down to the point where said curves and side tracks commence, and the city shall grant its permission so to fill up its tracks, it should also fill up at the same time and to an equal height, all the space between the track so filled up and the lake shore as it now exists, from the north side of Randolph street down to the point where said curves and side tracks intersect the line fixed by the ordinance aforesaid.” The company's tracks were curved as permitted; the street referred to was opened, and has ever since been used by the public; and the required filling was done. It being necessary that the railroad company should have additional means of approaching and using its station grounds between Randolph street and the Chicago river, the city, by another ordinance adopted September 15, 1856, granted it permission “to enter and use in perpetuity, for its line of railroad and other works necessary to protect the same from the lake, the space between its present [then] breakwater and a line drawn from a point on said breakwater 700 feet south of the north line of Randolph 745extended, and running thence on a straight line to the south-east corner of its present breakwater, thence to the river: provided, however, and this permission is only given upon the express condition that, the portion of said line which lies south of the north line of Randolph street extended shall be kept subject to all the conditions and restrictions, as to the use of the same, as are imposed upon that part of said line by the said ordinance of June 14, 1852.” In 1867 the company made a large slip just outside of the exterior line fixed by the ordinance of 1852, thereby extending its occupancy between Randolph street and Chicago river further to the east. Along the outer edge of this pier a continuous line of dock piling was placed, extending on a line from the river to the north line of Randolph street, 1,792 feet distant from the west line of Michigan avenue. This line formed the company's breakwater between the river and Randolph street at the time of the passage (April 16, 1869) of what is known as the “Lake Front Act.” In view of the important questions raised, and of the rights asserted, under that act, it is here given in full:

“An act in relation to a portion of the submerged lands and Lake Park grounds, lying on and adjacent to the shore of Lake Michigan, on the eastern frontage of the city of Chicago.

“Section 1. Be it enacted by the people of the state Of Illinois, represented in the general assembly, that all right, title, and interest of the state of Illinois in and to so much of fractional section 15, township thirty-nine, range fourteen east of the third principal meridian, in the city of Chicago, county of Cook, and state of Illinois, as is situated east of Michigan avenue and north of Park row, and south of the south line of Monroe street, and west of a line running parallel with and four hundred feet east of the west line of said Michigan avenue,—being a strip of land four hundred feet in width, including said avenue, along the shore of Lake Michigan, and partially submerged by the waters of said lake,—are hereby granted in fee to the said city of Chicago, with full power and authority to sell and convey all of said tract east of said avenue, leaving said avenue ninety feet in width, in such manner and upon such terms as the common council of said city may by ordinance provide: provided, that no sale or conveyance of said property, or any part thereof, shall be valid, unless the same be approved by a vote of not less than three-fourths of all the aldermen elect.

“Sec. 2. The proceeds of the sale of any and all of said lands shall be set aside, and shall constitute a fund, to be designated as the ‘Park Fund’ of the said city of Chicago; and said fund shall be equitably distributed by the common council between the South division, the West division, and the North division of the said city, upon the basis of the assessed value of the taxable real estate of each of said divisions, and shall be applied to the purchase and improvement in each of said divisions, or in the vicinity thereof, of a public park or parks, and for no other purpose whatsoever.

“Sec. 3. The right of the Illinois Central Bailroad Company under the grant from the state in its charter, which said grant constitutes a part of the consideration for which the said company pays to the state at least seven per cent. Of its gross earnings, and under and by virtue of its appropriation, occupancy, use and control, and the riparian ownership incident to such grant, appropriation, occupancy, use, and control, in and to the lands, submerged or otherwise, lying east of the said line, running parallel with and 400 feet east of the west line of Michigan avenue, in fractional sections ten and fifteen, township and range as aforesaid, is hereby confirmed; and all the right and title of the state of Illinois 746in and to the submerged lands constituting the bed of Lake Michigan, and lying east of the tracks and breakwater of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, for the distance of one mile, and between the south line of the south pier extended eastwardly and a line extended eastward from the south line of lot twenty-one, south of and near to the round-house and machine-shops of said company, in the South division of the said city of Chicago, are hereby granted in fee to the said Illinois Central Railroad Company, its successors and assigns: provided, however, that the fee to said lands shall be held by said company in perpetuity, and that the said company shall not have power to grant, sell, or convey the fee to the same; and that all gross receipts from use, profits, leases, or otherwise of said lands, or the improvements thereon, or that may hereafter be made thereon, shall form a part of the gross proceeds, receipts, and income of the Baid Illinois Central Railroad Company, upon which said company shall forever pay into the state treasury, semi-annually, the per centum provided for in its charter, in accordance with the requirements of said charter: and provided, also, that nothing herein contained shall authorize obstructions to the Chicago harbor, or impair the public right of navigation; nor shall this act be construed to exempt the Illinois Central Railroad Company, its lessees or assigns, from any act of the general assembly which may be hereafter passed regulating the rates of wharfage and dockage to be charged in said harbor: and provided, further, that any of the lands hereby granted to the Illinois Central Railroad Company, and the improvements now, or which may hereafter be, on the same, which shall hereafter be leased by said Illinois Central railroad Company to any person or corporation, or which may hereafter be occupied by any person or corporation other than said Illinois Central Railroad Company, shall not, during the continuance of such leasehold estate or of such occupancy, be exempt from municipal or other taxation.

“Sec. 4. All the right and title of the state of Illinois in and to the lands, submerged or otherwise, lying north of the south line of Monroe street, and south of the south line of Randolph street, and between the east line of Michigan avenue and the track and roadway of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, and constituting parts of fractional sections ten and fifteen in said township thirty-nine, as aforesaid, are hereby granted in fee to the Illinois Central Railroad Company, the Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad Company, and the Michigan Central Railroad Company, their successors and assigns, for the erection thereon of a passenger depot, and for such other purposes as the business of said company may require: provided, that upon all gross receipts of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, from leases of its interest in said grounds, or improvements thereon, or other uses of the same, the per centum provided for in the charter of said company shall forever be paid in conformity with the requirements, of said charter.

“Sec. 5. In consideration of the grant to the said Illinois Central, Chicago, Burlington: and Quincy, and Michigan Central Railroad Companies of this land as aforesaid, said companies are hereby required to pay to said city of Chicago the sum of eight hundred thousand dollars, to be paid in the following manner, viz.: Two hundred thousand dollars within three months from and after the passage of this act; two hundred thousand dollars within six months from and after the passage of this act; two hundred thousand dollars within nine months from and after the passage of this act; two hundred thousand dollars within twelve months from and after the passage of this act,—which said sums shall be placed in the Eark fund of the said city of Chicago, and shall be distributed in like manner as is hereinbefore provided for the distribution of the other funds which may be obtained by said city from the sale of the lands conveyed to it by this act.

“Sec. 6. The common council of the said city of Chicago is hereby authorized and empowered to quitclaim and release to the said Illinois Central Railroad 747Company, the Chicago, Burlington and Quiney Bailroad Company, and the Michigan Central Railroad Company any all claim and interest in and upon any and all of said land north of the south line of Monroe street, as aforesaid, which the said city may have by virtue of any expenditures and improvements thereon or otherwise; and in case the said common council shall neglect or refuse thus to quitclaim and release to the said companies, as aforesaid, within four months from and after the passage of this act, then the said companies shall be discharged from all obligation to pay the balance remaining unpaid to said city.

“Sec. 7. The grants to the Illinois Central Railroad Company contained in this act are hereby declared to be upon the express condition that said Illinois Central Railroad Company shall perpetually pay into the treasury of the state of Illinois the per centum on the gross or total proceeds, receipts, or income derived from said road and branches stipulated in its charter, and also the per centum on the gross receipts of said company reserved in this act.

“Sec. 8. This act shall be a public act, and in force from and after its passage.

“Passed, over veto, 16th April, 1869.”

As early as May, 1869, the railroad company caused to be prepared a plan for an outer harbor at Chicago. On the 12th of July of the same year the Illinois Central Railroad Company, the Michigan Central Railroad Company, and the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad Company, by an agent, tendered to Walter Kimball, the comptroller of the city of Chicago, the sum of $200,000, as the first payment to the city under the fifth section of the act of 1869. He received the sum tendered upon the express condition that none of the city's rights be thereby waived, or its interest in any manner prejudiced, and placed the money in bank on special deposit, to await the action and direction of the common council. The matter being brought to the attention of that body, it adopted, June 13, 1870, a resolution declaring that the city “will not recognize the act of Walter Kimball in receiving said money as binding upon the city, and that the city will not receive any money from railroad companies under said act of the general assembly until forced to do so by the courts.” The city never quitclaimed or released, nor offered to quitclaim or release, to said companies, or to either of them, any right, title, claim, or interest in or to any of the land described in the act of 1869, nor was Kimball's act in receiving the money ever recognized by the city as binding upon it. On the expiration of his term of office, he did not turn the money over to his successor in office, but kept it deposited in bank to his own individual credit; and so kept it until some time during the year 1874, or later, when, upon application by the railroad companies, he returned it to them. No other money than the $200,000 delivered to Kimball was ever tendered by the railroad companies, or either of them, to the city or to any of its officers. At a meeting of the board of directors of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, held at the company's office in New York, July 6, 1870, a resolution was adopted to the effect “that this company accepts the grants under the act of the legislature at its last session, and that the president give notice thereof to the state, and that the company has commenced work upon the shore of the lake at Chicago under the grants referred to.” 748On the 17th of November, 1870, its president communicated a copy of this resolution to the secretary of state of Illinois, and gave the notice therein required, adding: “You will please regard the above as an acceptance by this company of the above-mentioned law, [Lake Front act,] and it is desired by said company that said acceptance shall remain permanently on file and of record in your office.” The secretary of state replied, under date of November 18, 1870: “Yours of the 17th inst., being a notice of the acceptance by the Illinois Central Railroad Company of the grants under an act of the legislature of Illinois, in force April 16, 1869, was this day received, and filed, and duly recorded in the records of this office.”

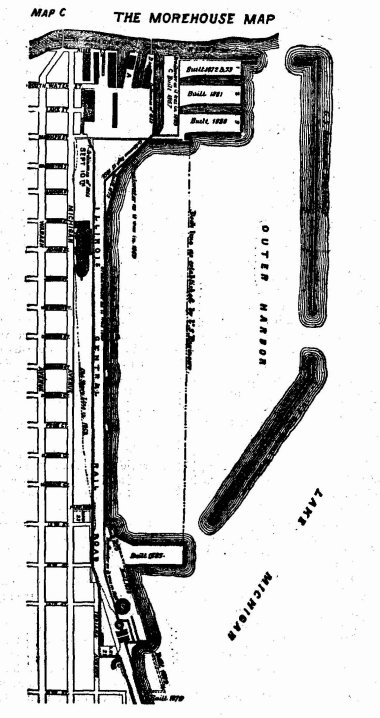

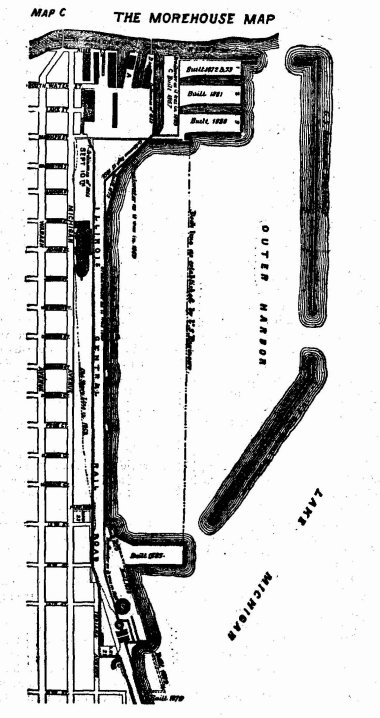

Following these transactions were certain proceedings, commenced about July 1, 1871, by information filed in this court by the United States against the Illinois Central Railroad Company. That information set forth that congress, in order to promote the convenience and safety of vessels navigating Lake Michigan, had, from time to time, appropriated and expended large sums of money in and about the mouth of Chicago river, and had constructed two piers extending from the north and south banks of that river eastwardly for a considerable distance into the lake; that in July, 1870, it appropriated a large sum of money to construct an outer harbor at Chicago, in accordance with the plans of the engineer department of the United States; that the railroad company had, from time to time, wrongfully filled up with earth a portion of said lake within said harbor; that what the company had then done, in that way, and what it intended to do, unless prevented, would materially interfere with the execution of the plan of improvement adopted by the war department. A temporary injunction was issued against the company. Subsequently, in 1872, the parties to that suit entered into a stipulation, from which it appears that the matters referred to in said information relating to the construction of docks and wharves in the basin or outer harbor of the city, formed by the breakwater then in process of erection by the United States, were referred to the war department, and that the secretary, upon the recommendation of engineer officers, approved certain lines limiting the construction of docks and wharves in said outer harbor, to-wit: Commencing at the pier on the south side of the entrance to the Chicago river, 1,200 feet west of the government breakwater; thence south to an intersection with the north line of Randolph street extended eastwardly; thence due west 800 feet; and thence south to the east and west breakwater proposed to be constructed by the United States, 4,000 feet south of the pier first above mentioned,—the line so established being fixed as the line to which docks and wharves may be extended by parties entitled to construct them within said outer harbor. The railroad company desiring to proceed, under the supervision of the engineer bureau of the United States, with the construction of docks and wharves within the proposed outer harbor, between the pier on the south side of the entrance to Chicago river and the north line of Randolph street extended eastwardly, in conformity with the said limiting lines, and having agreed: to observe said lines, as well as the directions which 749might be given in reference to the construction of said docks and wharves by the proper officers of said bureau, the injunctional order, pursuant to stipulation between the parties, was, January 16, 1872, vacated, and the information dismissed, with leave to the United States to reinstate the same upon the failure of the company, in good faith, to observe the said conditions. Subsequently the railroad company resumed work on, and during the year 1873 completed, pier No. 1, adjacent to the river, and east of the breakwater of 1869. On the 15th of April 1873, the legislature of Illinois passed the following act, which was in force from and after July 1, 1873: “Section 1. Be it enacted,” etc., “that the act entitled ‘An act in relation to a portion of the submerged lands and Lake Park grounds lying on and adjacent to the shore of Lake Michigan, on the eastern frontage of the city of Chicago,’ in force April 16, 1869, be, and the same is hereby, repealed.” In 1880 and 1881, piers Nos. 2 and 3, north of Randolph street, were constructed in conformity with plans submitted to and approved by the war department. The common council of Chicago, by ordinance approved July 12, 1881, extended Randolph street eastwardly, and declared it to be a public street, from its then eastern terminus “to the west line of the right of way of the Illinois Central Railroad Company, as established by the ordinance of September 10, 1855, * * * and also straight eastwardly * * * from the easterly line of slip C, produced southerly to Lake Michigan;” giving permission to the company to construct and maintain at its own expense, within the line of Randolph street so extended, and over the company's tracks and right of way, a bridge or viaduct, with suitable approaches, to be approved by the commissioners of public works, which should be forever free to the public, and to all persons having occasion to pass and repass thereon. Such a bridge or viaduct was necessary in order that the piers constructed, and in process of construction, east of the breakwater of 1869, might be conveniently reached by teams. The viaduct was built in 1881, and extends to the base of pier 3. It has ever since been used by the public. It appears from the evidence that, in 1882, the pier which was built in 1870 from Twelfth street to the north line extended of lot 21, was continued as far south as the center line of Sixteenth street. The main object of this extension, according to the showing made by the company, was to protect the tracts from the waves during storms from the north-east. Another object was to construct a slip or basin south of the south line of lot 21, between the breakwater and the shore, where vessels loaded with materials for the company, or having freight to be handled, could enter and be in safety. In 1885, a pier was constructed by the company at the foot of Thirteenth street, according to a plan submitted to the war department; and the department did not object to its construction, “provided no change be made in its location and length.” The pier as constructed does not differ from that proposed and approved, except that it is wider by 50 feet. But it does not appear that the war department regards that change in the plan as injurious to navigation, or as interfering with the plans of the government for an outer harbor. 750 At the hearing, a map was used for the purpose of showing the different works constructed by the United States; the location of all the structures and buildings erected by the railroad company, with the date of their erection; and the relation of the tracks and breakwaters of the company to the shore as it now is, and, to some extent, as it was heretofore. That map, known as the “Morehouse Map,” and called “C,” is reproduced.

The state, in the original suit, asks a decree establishing and confirming her title to the bed of Lake Michigan, and her sole and exclusive right to develop the harbor of Chicago by the construction of docks, wharves, etc., as against the claim by the railroad company that it has an absolute title to said submerged lands, described in the act of 1869, and the right—subject to the paramount authority of the United States in respect to the regulation of commerce between the states—to fill the bed of the lake, for the purposes of its business, east of and adjoining the premises between the river and the north line of Randolph street, and also north of the south line of lot 21; and also the right, by constructing and maintaining wharves, docks, piers, etc., to improve the shore of the lake, for the purposes of its business, and for the promotion, generally, of commerce and navigation. The state, insisting that the company has, without right, erected, and proposes to continue to erect, wharves, piers, etc., upon the domain of the state, asks that such unlawful structures be directed to be removed, and the company enjoined from constructing others. The city, by its cross-bill, insists that since June 7, 1839, when the map of Fort Dearborn addition was recorded, it has had the control and use for public purposes of that part of section 10 which lies east of Michigan avenue, and between Randolph street and fractional section 15; and that, as successor of the town of Chicago, it has had possession and control since June 13, 1836, when the map of Fractional Section 15 addition was recorded, of the lands in that addition north of block 23. It asks a decree declaring that it is the owner in fee, and of the riparian rights thereunto appertaining, of all said lands, and has, under existing legislation, the exclusive right to develop the harbor of Chicago by the construction of docks, wharves, and levees, and to dispose of the same, by lease or otherwise, as authorized by law; and that the railroad company be enjoined from interfering with its said rights and ownership. The relief sought by the United States is a decree declaring the ultimate title and property in the “Public Ground” shown on the plat of the Fort Dearborn addition, south of Randolph street, and also in the open space shown on the plat of Fractional Section 15 addition, to be in the United States, with the right of supervision and control over the harbor and navigable waters aforesaid; that the railroad companies and the city be enjoined from exercising any right, power, or control over said grounds, or over the waters or shores of the lake; that the Illinois Central Railroad Company be restrained from making or constructing any piers, wharves, or docks, and from driving piles, building walls, or filling with earth or other materials in the said lake, or from using any made-ground, or any piers, wharves, or other constructions made 751 752or built by or for it in or about the outer harbor, to the east of the 200-feet strip of its way-ground, or from taking or exacting any toll for such use; and that the Illinois Central Railroad Company be required to abate and remove all obstructions placed by it in said outer harbor, and to quit possession of all lands, waters, and made-ground taken and held by it without right as aforesaid. The state, the city, and the general government all unite in contending that the Lake Front act of 1869 is inoperative and void, for reasons that will be hereafter stated.

752or built by or for it in or about the outer harbor, to the east of the 200-feet strip of its way-ground, or from taking or exacting any toll for such use; and that the Illinois Central Railroad Company be required to abate and remove all obstructions placed by it in said outer harbor, and to quit possession of all lands, waters, and made-ground taken and held by it without right as aforesaid. The state, the city, and the general government all unite in contending that the Lake Front act of 1869 is inoperative and void, for reasons that will be hereafter stated.

In disposing of the questions discussed by counsel, it will be convenient to consider first those relating to the lands or grounds embraced in the Fort Dearborn addition to Chicago. It it apparent, from the facts stated, that whatever title the Illinois Central Railroad Company has to the water lots in that addition, between Randolph street and the Chicago river, is derived, as to some of them, directly, and, as to others, remotely, from the United States. It is, however, insisted, in behalf of the United States, that the subdivision and platting of Fort Dearborn reservation into blocks, lots, streets, and public grounds by Birchard was unauthorized by the act of 1819, under which alone he proceeded, or could have proceeded. The point made is that upon the secretary of war was conferred the power to dispose of military sites found to be useless, and that such power could not be delegated to or exercised by an agent, although specially appointed by him for that purpose. In this view the court does not concur. The direction in the act was that the secretary “cause to be sold” such military sites as were useless,—language implying that he might discharge the duty imposed by congress through the agency of some one representing him. It certainly could not have been expected that he would visit Chicago, and personally superintend the sale. The plat shows upon its face, and the United States admits in their information, that Birchard acted in the premises for the secretary of war, and only as his agent. It further appears that he acted under a power of attorney executed under the direction of the president.

But it is contended that the power to cause these lands to be sold did not authorize the secretary to dedicate a part of it to the public as streets and public grounds. And, in this connection, the district attorney maintains that the subdivision and platting by Birchard was not in conformity with the Illinois statute of February 27, 1833, for the recording of town plats. By the fifth section of that act, the plat or map, when made out and certified, acknowledged, and recorded, as required by the statute, was to be deemed, as to every donation or grant to the public therein specified, a sufficient conveyance to vest in the city the fee-simple of the lands so designated, and operated as a general warranty. It also declared that “the land intended to be for streets, alleys, ways, commons, or other public uses, in any town or city, or addition thereto, shall be held in the corporate name thereof, in trust to and for the uses and purposes set forth and expressed or intended.” It is contended that the dedication of the streets and the public grounds south of Randolph street, on the lake shore, did not conform to the statute, and was, at most, a dedication at common law; in which event, it is insisted, the 753fee to the streets and public grounds remains in the United States, notwithstanding the title must be held subject to the public uses by the platting and by the subsequent sales of lots with reference thereto. It seems to the court clear that the power given to the secretary to sell—no particular mode for selling being prescribed—carried with it, by necessary implication, authority to adopt any mode that was not unreasonable, in view of the object to be accomplished, and that was customary in the case of lands within the limits of or near to a town or city. If a subdivision, in the mode ordinarily adopted in the locality, of a large tract, so situated, into blocks, lots, streets, and public grounds, was likely to be beneficial to the government, it was the duty of the secretary to adopt that mode of selling. If the subdivision and platting by Birchard was in conformity to the local statute in all material respects, then no conveyance by the United States of the legal title to the streets and public grounds was necessary. If it did not conform to the local law, and if the dedication of the streets and public grounds, shown on the map of Fort Dearborn addition, is to be deemed only valid as a dedication at common law, it would not follow that the United States can have a standing in court in respect to such streets and public grounds. The argument by the district attorney upon this point proceeds upon the ground that the general government, after abandoning Fort Dearborn as a military site, and after having sold the whole of that reservation, except the parts reserved for streets and public grounds, had the capacity to hold the title to such streets and public grounds in trust for the public uses affixed to it. This position cannot be maintained. The United States took the right, title, and claim, as well of soil as of jurisdiction, which the commonwealth of Virginia had in the Northwest Territory, for the purposes only of temporal government, and in trust for the performance of the stipulations and conditions imposed by the deed of cession. It was accepted as a common fund for the use and benefit of all the states, Virginia included. One of those conditions was that the territory so ceded should be laid out and formed into states, having the same rights of sovereignty, freedom, and independence as the other states. Consequently, when Illinois was admitted into the Union, “upon the same footing with the original states, in all respects whatever,” she succeeded to all the rights of sovereignty, jurisdiction, and eminent domain which Virginia possessed at the date of the cession, “except so far as this right was diminished by the public lands remaining in the possession and under the control of the United States, for the temporary purposes provided for in the deed of cession, and of the legislative acts connected with it. Nothing remained to the United States, according to the terms of the agreement, but the public lands. And if an express stipulation had been inserted in the agreement, granting the municipal right of sovereignty and eminent domain to the United States, such stipulation would have been void and inoperative; because the United States have no constitutional capacity to exercise municipal jurisdiction, sovereignty, or eminent domain, within the limits of a state, except in the case in which it is expressly granted.” (Pollard's Lessee v. Hagan, 3 How. 212, 223; 754New Orleans v. U. S., 10 Pet. 662;) or where it is necessary to the enjoyment of the powers conferred by the constitution upon the general government, (Kohl v. U. S., 91 U. S. 367, 372; U. S. v. Fox, 94 U. S. 320; U. S. v. Jones, 109 U. S. 513, 519, 3 Sup. Ct. Rep. 346.) See, also, Van Brocklin v. State of Tennessee, 117 U. S. 151, 167, 168, 6 Sup. Ct. Rep. 670. When, therefore, Fort Dearborn reservation was subdivided into lots, and they were sold, with reference to the map or plat of such subdivision, and it was no longer used as a military site, or for any purpose connected with the execution of the powers of the general government, all the lands embraced within its limits ceased to be a part of the national domain, the title to the specific lots passed to those who purchased them, while jurisdiction over the streets and open grounds, dedicated to public use, passed from the United States; the title to, and immediate possession and control of, such streets and grounds, vesting in the local government,—that is, in the municipal corporation of Chicago,—as a public agency of the state for the purposes for which such dedication was made. Touching the action of the secretary of war, and of his agent Birchard, it may also be said that its validity was impliedly recognized in the case, already referred to, of U. S. v. Chicago. The question there was, as we have seen, whether the city had the right to open streets designated on the Birchard plat through that part of Fort Dearborn reservation which had not then been sold, and was still used by the general government as a military site. If the Birchard subdivision was invalid, upon the ground that the secretary could not invest him with power to do what he did, it would have been a ready answer, in that case, to the city's claim of authority to open Michigan avenue through Fort Dearborn reservation to the river, to say that Birchard's subdivision and platting, upon which the city relied, did not bind the United States. On the contrary, the decision proceeded upon the ground that the subdivision and platting was legal, although not done under the personal supervision of the secretary of war; and that the right of the city to open Michigan avenue, as marked on the Birchard map, through that part of the reservation not then sold, would not come into existence until the occupancy of the United States ceased. Whatever doubt may remain upon this point is removed by the act passed by congress, August 1, 1854, for the relief of Jean Baptiste Beaubien, by which the commissioner of the general land-office was authorized to issued to him a patent or patents for certain specified “lots as described and numbered on the survey and plat of the Fort Dearborn addition to Chicago, in the state of Illinois, made under the order of the secretary of war, and now on file in the war-office.” This statute is so far a recognition or ratification of the Birchard subdivision, and of the acts of the secretary of war, as to preclude the United States and all others from making any question as to his power to make sale of Fort Dearborn reservation through the agency of Birchard, or as to the authority of the agent to subdivide these lands into blocks, lots, streets, and public grounds.

What has been said is sufficient to show that the United States have long since parted with all jurisdiction over or title to the lands embraced 755within that reservation, and that the Illinois Central Railroad Company, shortly after the location of its road within the corporate limits of Chicago, acquired a title in fee to all of the water lots on the lake shore within the Fort Dearborn addition north of Randolph street.