THE NICHOLSON AND THE ADAMS.1

District Court, N. D. New York.

October 18, 1886.

1. COLLISION—MOORING OF VESSEL—SPACE OCCUPIED—LOCAL ORDINANCE—VESSEL MOORED—TUG AND TOW—NEGLIGENCE.

If a local ordinance permits the mooring of vessels, two abreast, and if the two together do not project as far into the river as a single vessel of the class constantly occupying the same space, the vessel at rest cannot, by reason of the circumstance that she is moored as aforesaid, be charged with negligence in being moored in an improper place.

2. SAME—TOW—HEAD-SAILS UNFURLED—NEGLIGENCE.

A tow is in fault if, in threatening weather, she enters a narrow fairway, filled with vessels, with her head-sails insufficiently secured, and, if this fault contributes to produce? a collision, she is chargeable with negligence

3. SAME—TUG—MEASURE OF SKILL AND CARE—NEGLIGENCE.

The degree of care required on the part of the tug must, obviously, be measured by the condition of the tow. To tow a large and deeply-laden schooner up a narrow and obstructed channel, at the rate of five or six miles an hour, with a hurricane blowing, and the tow's sails unfurled, is not good seamanship, and, if this lack of care contributes to a collision, she is chargeable with negligence.

In Admiralty. Action in rem, against tug and tow, by the owners of a vessel moored in a river.

George Clinton, for libelant.

H. C. Wisner, for the Nicholson.

George S. Potter, for the Adams.

COXE, J. The libel in this action is filed by John Wimett, the owner of the canal-boat R. Webb Potter, against the schooner Elizabeth A. Nicholson and the steam tug James Adams, alleging that on 890the evening of September 8, 1885, a collision, occasioned by their negligence, occurred between the schooner and the canal-boat, by which the latter received serious injury. The Adams is a large and powerful harbor tug. The Nicholson is a three-masted schooner, with a capacity of 650 tons, carrying a square sail, square topsail, and top-gallant sail on her foremast.

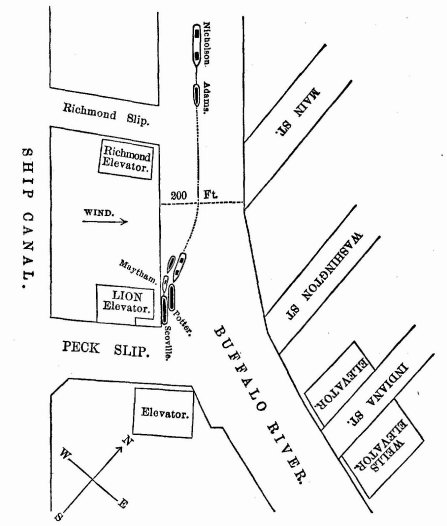

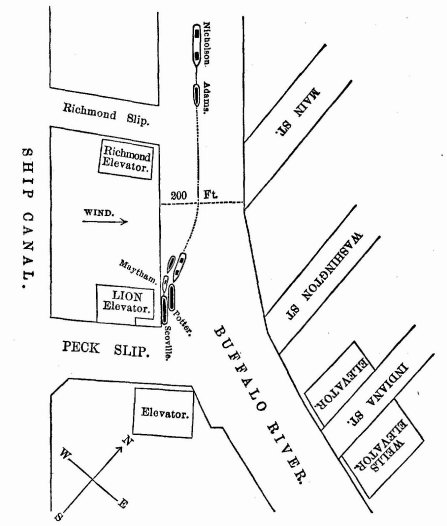

On the evening in question the Potter lay moored at the Lion elevator, near the entrance of Peck slip, on the westerly side of the Buffalo river, outside the steam canal-boat Scoville and the steam tug Maytham. It was a frequent occurrence for boats to lie at this point. The river for some distance below is about 200 feet in width, but at the point in question it is somewhat wider. During the early part of the evening the wind was light, blowing from the south-east and south, the velocity being about seven miles an hour. At 10 P. M., as appears by the record of the United States signal office, it had increased to 18 miles, at 11 P. M. it was 14 miles, and at midnight 20 miles, per hour. At 11: 20 P. M. a very severe squall set in from the south-west, and continued until 11:55 P. M., the wind blowing from the lake, and directly across the river. At 11:45 the wind reached a maximum velocity of 35 miles per hour. The storm was accompanied by rain, thunder, and lightning. The night was very dark. The Adams had taken the Nicholson in tow some three miles up the lake, having two lines from the schooner,—one from the port, and another from the starboard, bow. Her destination was the Wells elevator, some 900 feet beyond where the Potter lay, and on the opposite side of the river. The Nicholson was heavily loaded, drawing about 14 feet of water. Her square sails were not securely furled, but hung loose in the gearing. The clews were hauled up close, but when the squall struck them the bunt-lines of the lower sail gave way, leaving about two-thirds of its surface exposed. The yards were braced around to port, so that the sails would draw when the wind struck them. The schooner and tug had arrived at the entrance to the harbor before the squall became serious. The schooner sheered badly, and the tug signaled for assistance, but continued her course up the river, at the rate of between five and six miles per hour. When near the Richmond elevator the tug dropped the port line, backed to the starboard bow of the schooner, and made a line fast to her timberhead, near the bow. At about the same time another tug, the Annie P. Dorr, came to the assistance of the Adams, and took a line from the starboard quarter of the schooner. Soon afterwards the Nicholson sheered to starboard and struck the Potter on the starboard corner of the stern, two feet from the side, breaking the lines which held her to the other boats. The stem of the Adams struck the stern of the Maytham, and the line from the tug to the schooner was parted. The Potter swung out from her moorings, and, before she could be again secured, another schooner, the Michigan, struck her, causing additional damage. 891 The accident may be more clearly understood by an examination of the accompanying diagram.

There is here a triangular contest, in which each boat insists that she is blameless, and that the collision was occasioned by the carelessness of the other two.

It is entirely clear that the accident was not, in a legal sense, an inevitable one. It is only when safe navigation is rendered impossible from causes which no human foresight can prevent—when the forces of nature burst forth in unforeseen and uncontrollable fury, so that man is helpless, and the stoutest ship and the wisest mariner are at the mercy of the winds and waves—that such accidents occur. 892The collision here could have been prevented; therefore it was not inevitable. It is also true that no one of the three boats concerned would have been managed as it was if the sudden and almost unprecedented gale had been anticipated.

Negligence is imputed to the Potter in two particulars. It is said that she exhibited no light, and that she was moored in an improper place. The master of the Potter testifies positively that when he retired for the night he placed a light upon her forward cabin, and when he came on deck after the collision it was still burning. The proof that there was a light at all times on the Scoville is even more satisfactory. Opposed to this is the testimony of the crews of the tugs and schooner that they saw no light. When it is remembered that the night was dark and misty, that the schooner was destined for the Wells elevator, on the opposite side of the river, and that there was nothing to direct the attention of the sailors to the point where the canal-boats lay until after the schooner luffed, it is not surprising that they did not observe the lights. After the schooner took the sheer, there was little time for observation; the few minutes that elapsed before the collision were moments of intense excitement. The business in hand was sufficiently urgent to absorb the attention of every one on the three vessels, and, if the lights on the canal-boats had been far more brilliant than they were, it is quite probable that no one would have observed them. But I am fully convinced that had the light been absent it would not have contributed in the remotest degree to the accident. If the collision is attributed to the fault of the tug, the great weight of testimony proves that her captain would have taken the same course if he had known the precise location of the canal-boats at the Lion elevator. Indeed, he did know of the position of the tug Maytham, for she had for several days been tied up at that point. If, on the other hand, the collision is attributed to the fault of the schooner, it is entirely clear that she luffed from causes which could not have been affected by any number of lights at that point in the river. The tug would not, and the schooner could not, have taken a different course.

Regarding the position of the Potter, it cannot, upon this proof, be held to be improper. No regulation forbade two canal-boats from lying abreast at that point. The two together did not project into the river as far as one of the larger steam or sail vessels which constantly lie along the docks. The court has heretofore considered several causes where it appeared that canal-boats not only, but large vessels, were moored, three and four abreast, at dangerous points,—so dangerous, in fact, that an argument inculpating them could easily have been constructed, for the city ordinances forbid more than two vessels from lying abreast,—and yet the subject was not alluded to except incidentally. When a proper case arises, the court should not hesitate to condemn the practice, but there would be little propriety in pronouncing that to be negligence which is permitted by 893local regulations, and which, perhaps, is rendered necessary by the crowded character of the harbor. The frequent occurrence of collisions which, were it not for this custom, might, perhaps, be prevented, ought, it would seem, to require more stringent rules in this regard in the future, or, at least, the strict enforcement of the existing ordinances.

An examination of the voluminous testimony submitted leaves the mind in doubt as to the proximate cause of the accident. So many opposing opinions and conflicting theories are advanced—there is such a marked conflict as to what took place just prior to the collision—that anything like demonstration is out of the question. It is thought, however, that the evidence discloses negligence on the part of both the schooner and the tug, and that the disaster must be attributed to their joint fault.

First, as to the Nicholson. It is sufficiently established that her head-Bails were not properly secured. Two-thirds of one of them, owing to the defective bunt-lines giving way, was exposed to the wind. As she passed up the river the wind through the slips caught her head-sails, and turned her bow to port. To counteract this, it was necessary, at such times, to keep her helm a-port. The next moment, as she came under the lee of the elevators and large structures on the westerly bank, the sails came becalmed, and the wind struck her starboard quarter. This, especially with a port helm, tended to throw her stern to port and her bow to starboard, and necessitated a quick change of helm from port to starboard, and vice versa, as occasion demanded. To thus enter a narrow fairway, filled with vessels, stationary and moving, would be questionable seamanship at any time, and in any circumstances; but with a storm threatening,—and there is evidence of ominous signals in the sky before the harbor was reached,—it was a grave fault. That it made navigation in the harbor more hazardous is conceded. The schooner had exhibited a tendency to become unruly lower down the river, near the coal shutes. It can hardly be disputed that with her port braces hauled in, and her head-sails alternately drawing and becalmed, necessitating frequent and skillful changes of the helm, she was not in a condition to be easily handled. Indeed, it is quite clear from the testimony that her helm was not put hard a-starboard at any time after passing the Richmond slip, and, if put to starboard at all at that point, it was not done in time to prevent the sheer. Had her jibs or foresail been up and drawing, her fault would have been admitted by all, and it must be held that the actual condition of her head-sails was negligence, only in a less degree, and contributed to produce the accident. It is not necessary to examine the other acts of carelessness imputed to the schooner. They are disputed, and the one alluded to is sufficient to justify a decree against her.

Was the Adams at fault? It is true that a tug is not a common carrier or insurer. The highest possible degree of skill is not required 894of her. She is bound, however, to exercise reasonable skill and care in the discharge of her duties. The law requires her to know and guard against the perils of the harbor, to select the safest and best way to reach the point of destination, and to determine whether, in the existing state of wind and water, it is safe to proceed with her tow. The Nicholson, after she entered the harbor, was, in fact and in law, under control of the tug. The condition of the head-sails of the schooner was obvious to those on board the tug. The master of the tug saw them hanging loose in the gearing. Knowing the intricacies of the harbor, he could appreciate the danger from this source more fully than the master of the schooner. The degree of care which he assumed must be measured by the obviously dangerous condition of the tow. Greater skill and prudence was required. What might have been skillful seamanship on a calm, moonlight night must be regarded as bad seamanship when the condition of the elements on the night in question is considered. Stated generally, it was imprudent for the Adams to tow a large and deeply-loaded schooner, with her head-sails unfurled, up a narrow and obstructed channel, at the rate of five or six miles an hour, on an intensely dark night, with a hurricane blowing from the south-west. It is true that the sudden squall put both vessels in an awkward and hazardous situation; and though it is by no means easy, upon this proof, to determine which of the courses suggested the Adams should have adopted, it is quite certain that she should not have taken the course she did, which was the most perilous of them all. When just inside the pier at the light-house the squall burst upon them. The tug knew that she would have difficulty in controlling a vessel so circumstanced as the Nicholson. She could have checked down, and gone alongside of the schooner, and waited for assistance, where there was ample sea-room to maneuver. Even had she proceeded, it was not necessary for her, in the teeth of the harbor regulations, to proceed at so high a rate of speed.

Again, it was bad seamanship for the Adams, at the Richmond elevator, when the Dorr was at hand, and in a moment more would have had a stern-line fast, to give up all control of the Nicholson, knowing that she was almost certain to sheer the moment the line was thrown off. Whether the tug backed or not after she reached the schooner's bows it is almost impossible to determine. If, as she insists, the bluff of her port bow was on the schooner's starboard bow, and she was pushing the latter over under a starboard helm, using all the power she possessed, it is difficult to understand how her stem could have struck the stern of the Maytham. To reconcile the two positions would puzzle the most accomplished expert.

It follows that the libelant is entitled to a decree against the Adams and the Nicholson. A moiety of the entire damages, interest, and costs, should be charged against each vessel, severally, according 895to the rule laid down in The Alabama, 92 U. S. 695, and The Washington, 9 Wall. 513.

There should be a reference to the clerk to compute the damages.

1 Reported by Theodore M. Etting, Esq., of the Philadelphia bar.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.