THE TROY.1

District Court, N. D. New York.

October 9, 1886.

COLLISION—TUG AND TOW—NEGLIGENCE—RECOVERY AGAINST ONE OR BOTH VESSELS.

When a collision is caused by the negligence of two vessels, proof that the disaster could have been prevented by one of them is not sufficient to exculpate the other. The entire damage may be recovered from one vessel, though both be in fault, if one only is served.

In Admiralty.

George Clinton, for libelant.

S. B. Porter, for claimant.

COXE, J. The owner of the canal-boat S. H. Fish brings this action against the steam-tug Troy to recover damages occasioned by her negligence in causing, or contributing to cause, a collision between the canal-boat and the steam-tug Rambler. In the libel, which was filed July 13, 1880, both tugs were made parties, and the collision is there attributed to their joint negligence. For some reason, not fully explained, the Rambler was not served with process, and is now, beyond the jurisdiction of the court.

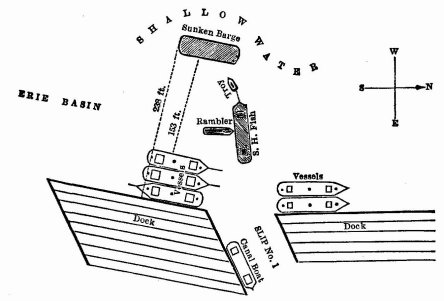

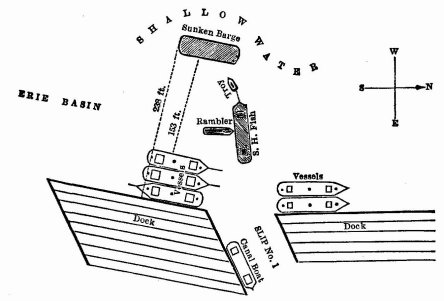

On the morning of the first of November, 1879, the libelant employed the Troy to tow his canal-boat, from a point in the Erie canal near Baker's dock, to the Niagara elevator, on the Buffalo river, where she was to take in a cargo of wheat. The route lay through slip. No. 1 and the Erie basin. The channel in the basin at this point, owing to a sunken barge and shallow water opposite the slip, is about 238 feet wide. On the day in question three vessels were lying at the southerly corner of the slip, projecting into the basin some 85 feet; thus reducing the width of the channel to 153 feet. Two vessels of about similar dimensions were lying abreast at the northerly corner of the slip. The canal boat was about 97 feet in length, the Troy 48 feet, and the line between them 7 feet, so that the distance from the stem of the tug to the stern of the canal-boat was 152 feet, or but a foot less than the width of the channel between the vessels and the sunken barge. The Rambler, a larger tug than the Troy, was proceeding, at the usual rate of four miles an hour, down the Erie basin, when the Troy, with her tow, headed west, and going at the rate of three miles an hour, emerged from the slip. The Troy proceeded on her course; and, when she was within a short distance of the sunken barge, the canal-boat, which then was moving directly across the channel, was struck by the Rambler on her port side, forward of amidships, and nearly opposite the forward hatch. The blow caused her to sink soon afterwards. 862 The situation can be better illustrated by a diagram than by words

The collision took place between 9 and 10 o'clock, in broad daylight. The weather was clear, and there was but little wind. There is some dispute as to whether the tug Troy gave any signal while in the slip. Those on the Rambler and the Fish heard none. The claimant's positive testimony that she blew three blasts when opposite the Exchange elevator, near the entrance to the Blip, should, however, be accepted as true.

It is conceded by all that the canal-boat was helpless, and therefore without fault. It may also be regarded as proved that the Rambler was guilty of negligence. The court so intimated at the argument, and no reason is seen for changing the opinion then formed. That a powerful tug, unincumbered by a tow, could have avoided such a collision, is a proposition almost self-evident. But the Rambler is not now before the court, and the inquiry must therefore be wholly confined to the Troy. Was she at fault? Could she have avoided the collision?

The theory of the claimants apparently is that they are exculpated when it is shown that the Rambler could have prevented the accident; that, because the proper way for a tug with a tow to pass out of slip No. 1 is to go straight across the channel, it follows, as a necessary conclusion, that this course must be pursued in all circumstances, and without reference to the danger confronting her. This proposition cannot be maintained. A party who is compelled to cross a railroad track in order to reach his destination, and who, without making the slightest effort to ascertain whether the track is clear, 863drives his team in front of an advancing train, and wrecks his wagon, cannot escape the charge of negligence by proving that the engineer, by reversing his engine and applying the air-brakes, might have avoided the accident.

The channel through the basin was the regularly traveled route where vessels were constantly passing and repassing. Slip No. 1 was a comparatively untraveled water-way. On the day in question, egress was rendered particularly dangerous by reason of the vessels lying abreast at each side of the entrance. The sunken barge opposite made the channel a narrow one at all times, but these obstructions reduced it to 153 feet. The master of the Troy knew all this. He knew that, in order to take his tow up the basin, it was necessary for him to run across and completely block the channel. He could see neither north nor south until the tug had passed the outmost vessel. He did not know but a tug with a heavy tow, or a large vessel, not easily controlled, was about passing the slip; and yet, without taking any extraordinary means to ascertain the situation, without slackening his speed, without giving any but the ordinary signal, which indicated that a tug was in the slip, and nothing more, he ran out directly across the channel. The canal-boat was thus caught in a trap without power to protect herself. The situation was unusual. It demanded unusual precautions. The failure to take them was negligence. The testimony is undisputed that the Troy was handled precisely as she would have been if the channel had been clear. But, even after the tug had reached the middle of the channel, she might, it seems, have prevented the collision. The Rambler did not know that the Troy had a tow until the line became visible. She was not called upon to stop until this fact was apparent. It was entirely obvious that the Troy alone could have crossed, as she did cross, with entire safety. But the Troy knew that she had a tow. She saw the Rambler bearing down upon her, without diminution of speed or change of course, until she was about 100 feet away. The Rambler was then informed that the Troy had a tow, and the Rambler was reversed. Why was not the Troy reversed? The evidence on the part of the libelant is not as full upon this point as it might have been. The court, however, being frequently called upon to deal with the relations of tugs to their tows, may take judicial notice of what a tug can do in certain circumstances.

It is in evidence that the Rambler, a much larger tug, and going at a greater rate of speed, could have been stopped in from 15 to 20 feet. The Troy certainly could have been stopped within the same space. If, on emerging into the basin, the Troy had given the danger signal, immediately reversed, and stopped the canal-boat which was unloaded, and therefore more easily controlled, it is quite certain that the injury would have been averted. So, too, she might have ported and gone to the north. In this way the blow would have been avoided altogether, or, if received, it would have been a glancing 864blow, and comparatively harmless. It is true that the situation after the Troy had passed into the channel was a difficult and an embarrassing one. Almost any maneuver suggested might have been attended with Borne injury to the canal-boat, and to the jib-booms and head-gearing of the adjacent vessels, but any course was preferable to running directly across the bows of a large and powerful tug which was rapidly approaching, and which had shown no inclination to stop or change her course. In the one case the danger was imminent, and the consequence of a collision serious; in the other, it was contingent and remote, and in any event but slight injury could ensue.

There is not the slightest doubt in the mind of the court that the collision was caused by the fault of both tugs; but as the Troy is the only one proceeded against, and as the Rambler is not now within the jurisdiction of the court, the recovery, so far as the present cause is concerned, must be against the Troy alone. The Atlas, 93 U. S. 302.

There should be a decree for the libelant, with costs, and a reference to compute the amount due.

1 Reported by Theodore M. Etting, Esq., of the Philadelphia bar.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.