THE ALPHA.1

THE ONEIDA.

The MANITOWOC.

TISDALE v. THE ALPHA and others.

District Court, N. D. New York.

June 2, 1886.

COLLISION—VESSELS IN TOW—MANEUVER IN EXTREMIS—STRENGTH OF HAWSER—UNNECESSARY AND EXTRAORDINARY STRAIN.

The canal-boat B., owned by the libelants, collided with the barge M. Each vessel was in charge of its own tug, and both were without other motive power. When about one-fourth of a mile apart, and in mid-channel, signals were exchanged. When a few hundred feet to the westward of libelants' ship, the M.'s hawser parted, and she was forced obliquely across the river, and collided with the Q. The libelant's tug maneuvered in accordance with the course indicated by signal until after the parting of the hawser, and, when confronted with the sudden peril incident thereto, the master of libelant's tug used his best judgment in maneuvering. The collision was caused by subjecting the M.'s hawser to an unusual and extraordinary strain, in consequence of which it parted. Held, that the master of libelant's tug was justified in presuming that the M.'s tug would take the course indicated by signal, and was under no obligation to stop or to maneuver as if anticipating an accident, and that, when confronted with a sudden peril, the only obligation imposed by law was the use of his best judgment. Held. further, that if the hawser was strong enough to stand any ordinary strain, and if it was, without cause, subjected to an extraordinary strain, the M.'s tug was chargeable with negligence.

In Admiralty.

Benjamin H. Williams, for libelant.

Josiah Cook, for the Alpha.

George Clinton, for the Oneida.

Willis O. Chapin, for the Manitowoc.

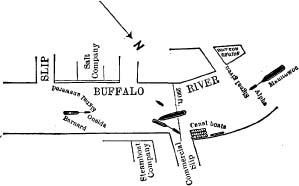

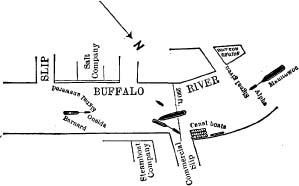

COXE, J. This is a collision case. On the thirteenth of May, 1885, the loaded canal-boat George Barnard, owned by the libelant, was proceeding down the Buffalo river in tow of the steam-tug Oneida, destined for the Erie canal via the Commercial slip. At the same time the tug Alpha was steaming up the river, having in tow the 760Manitowoc, a large barge, 225 feet long, and 25 feet and 9 inches beam. Both the canal-boat and the barge were without motive power, and each was wholly under the control of its respective tug. When the tugs were about a quarter of a mile apart, and nearly in the center of the river, the Alpha gave one blast upon her whistle, and was answered by a corresponding blast from the Oneida. This signal meant that the Alpha would go to the right, and that the Oneida must do the same. The latter's response indicated that she understood the Alpha's signal, and would do as requested, viz., keep to the right. When a few hundred feet west of Commercial slip the Alpha permitted the Manitowoc to run ahead of her, the line between them parted, and the barge, being thus adrift and uncontrollable, proceeded obliquely across the river, and struck the canal-boat on her port quarter, just abaft of the cabin, causing the injuries complained of. The river at the point of collision is about 290 feet wide. At the north-west corner of the Commercial slip three canal-boats were lying abreast, extending about 54 feet into the channel. The following diagram mav serve to illustrate the situation:

The collision was not inscrutable. Some one was at fault. Who was it? No negligence is imputed to the Barnard. She did all that was possible to avert the accident. This was practically conceded on the argument. Regarding the Oneida, also, the proof discloses no well-founded accusation. It is said that the accident might have been avoided if she had stopped, or passed on down the river between the canal-boats and the Manitowoc, or turned to the left, and passed the barge on her starboard side. The difficulty with this reasoning is that it assumes that the Oneida knew, or had reason to suspect, that the barge's line would part, and leave her helpless and unmanageable opposite the entrance to the slip. The Oneida presumed, and was 761justified in presuming, that the Alpha would take the course indicated by her signal, and go to the right. Had she done so there would have been no danger. The Oneida was on her own side of the river. She was proceeding in a proper manner and at an ordinary rate of speed. It would be a new and startling proposition in maritime law for the court to assert that it is the duty of vessels meeting in a wide water-way to stop when a quarter of a mile apart. If such a rule were enforced the vessels of our inland commerce would soon be “rotting at the walls.” After the line parted, the danger was imminent. There was no opportunity for nice and accurate calculations. If, confronted with this sudden peril, the master of the tug used his best judgment, it was all the law required of him. But the course he did take was, in the circumstances, the wisest for him to pursue. The Barnard almost escaped as it was. Had the Oneida attempted any of the maneuvers now suggested, the probability is that the disaster would have been more serious.

Coming now to the Alpha and the Manitowoc, it should be remembered that the latter was a large, heavily laden barge, depending solely upon the tug for locomotion. She was helpless the moment she was cast loose. It can be confidently affirmed, then, that the accident happened because the line parted. Through whose negligence did the hawser break? When this question is answered, the party responsible for the collision will be revealed.

The hawser furnished by the barge was an ordinary six-inch harbor line. It was nearly new, having been used but once before. A section of it was produced upon the hearing, and, although examined by hostile witnesses, no fault in it has been pointed out. Being strong enough to withstand any ordinary strain, it must have parted because subjected to an extraordinary strain. The master of the Alpha frankly admits that the hawser broke because he pulled too hard upon it. When within a few hundred feet of the slip, the tug, in her efforts to bring the barge safely around the curve, put her helm hard a-port, thus heading for the south side of the river. In this position the barge passed the tug, and, in seaman's parlance, “tripped her up.” They were proceeding against the current at the rate of about four miles an hour, their courses forming an angle of about 45 deg. A tremendous leverage was thus brought upon the hawser, which rolled the tug up almost upon her beam's end. No ordinary line could resist such a strain. It broke about a minute after the helm was put hard a-port. There can be no doubt that it was bad seamanship for the Alpha, with so short a line, and so heavy and unwieldy a tow, to permit herself to get into such a dilemma. This was negligence, and to it the collision is alone attributable. It follows that the libelant is entitled to a decree against the Alpha, with costs, and a reference to compute the amount due. As to the Oneida and the Manitowoc the libel is dismissed, without costs, but the Oneida is entitled to recover her disbursements of the libelant.

1 Reported by Theodore M. Etting. Esq., of the Philadelphia bar.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.