AMERICAN BELL TELEPHONE CO. and others v. NATIONAL IMPROVED TELEPHONE CO. and others.1

Circuit Court, E. D. Louisiana.

May 31, 1886.

1. PATENTS FOR INVENTIONS—TEMPORARY INJUNCTION—PRIOR DECISIONS.

Where patents have been the subject of judicial investigation, ending in decisions in the circuit courts of the United States maintaining their validity, so far as the issues presented in those causes have been identical with those involved in the case at bar, for the purposes of granting a preliminary injunction to run pendente lite, those prior decisions, elsewhere obtained, are sufficient.

2. ESTOPPEL—RES ADJUDICATA—WHO ARE BOUND, AND WHO NOT BOUND.

Parties who are bound by a judgment include all who are directly interested in the subject-matter, and had a right to make a defense, control the proceedings, examine and cross-examine witnesses, and appeal from the judgment. Persons not having these rights, substantially, are regarded as strangers to the cause; but all who are directly interested in the suit, and have knowledge of its pendency, and who refuse or neglect to appear and avail themselves of these rights, are equally concluded by the proceedings. Robbins v. Chicago, 4 Wall. 657, followed.

3. PATENTS FOR INVENTIONS—THE BELL TELEPHONE PATENT.

The court having reached the conclusion that the invention of Bell is set forth in the claim and specifications as originally filed, therefore any inquiry into the question whether, after the filing of Bell's application, his specifications and claims were changed in consequence of information derived through the examiner of the patent office from the caveat of Elisha Gray, would lead to nothing which could affect the validity of the patent. It is also found that Bell's invention did not lack novelty, and was not anticipated by Philip Reiss nor his successors.

In Equity. On rule for injunction.

J. J. Starrow, T. J. Semmes, T. L. Bayne, Geo. Denegre, E. N. Dickerson and Geo. L. Roberts, for complainants.

664J. R. Beck with, E. H. Farrar, E. B. Kruttschnitt, J. M. Bonner, and A. G. Brice, for defendants.

Before PARDEE and BILLINGS, JJ.

BY THE COURT. This cause is before us on an application for a preliminary injunction, upon bill, answers, numerous affidavits, depositions, and exhibits. We heard the application discussed by the solicitors on both sides, with many adjuncts of experiment and illustration, for the period of 21 days, and we have striven to give to the question the study and consideration to which it is entitled, from the fact that so many of our fellow-citizens throughout the entire country are interested in its decision. A very long discussion, in which solicitors of ability and learning participated,—such as has been the one conducted before us,—has one great advantage: it tends to separate, by a clear line of demarcation, that which is sound in law and sustained in fact, from that which, however plausible and forcibly urged, analysis and proof compel the abandonment of.

The complainants have urged that since the patents involved here have been the subject of judicial investigation, ending in decisions in the circuit courts of the United States maintaining their validity, that, so far as the issues presented in those causes have been identical with those involved in this cause, for the purposes of granting a preliminary injunction to run pendente lite, those prior decisions elsewhere obtained are sufficient. We assent to this doctrine.

The proofs submitted to us include decrees affirming these patents by Mr. Justice GRAY, Mr. Justice MATTHEWS, Judge LOWELL, Judge BLATCHFORD, Judge WALLACE, Judge NIXON, Judge MCKENNAN, Judge BUTLER, Judge ACHESON; with opinions at more or less length by Mr. Justice GRAY, Judge LOWELL, and Judge WALLACE. It has been urged by the respondents that in all these causes save one there was either an absence of one or more of the defenses here urged, or collusion between the parties, and consequent imposition upon the courts; so that the decrees and decisions submitted, and referred to above, should not of themselves be the basis of the decision and decree here. In the Molecular Case, decided by Judge WALLACE last June, there has been no charge of collusion, and consequent imposition. We think that these causes abundantly show that the substantial defenses here submitted have been urged in several of those cases, (though perhaps they have not been urged with the vigor and persistence that have characterized the defense here,) and that the settled practice in the circuit courts of the United States would authorize the granting of the injunction pendente lite upon the authority of the decrees in those cases. We do not understand that the weight given by one circuit court to the adjudications of another rests entirely upon the basis of comity, but as well upon that of recognized rights, and of convenience; and that it is largely to prevent the necessity of more than one court going through with the investigation 665of the same facts that the inference derived by the first court is for the purpose of determining whether or not an injunction shall go till the final decree, adopted by the other circuit courts. In addition to the weight to be given to the adjudications in favor of the Bell Company in other circuits on the basis of convenience, comity, and recognized rights, it is urged that the National Improved Telephone Company, the principal defendant here, is estopped by the final decree rendered by Judge MCKENNAN in the Pittsburg Case, because it was privy to that suit, and had a day in court there.

The evidence shows that the National Improved Telephone Company, claiming to own certain letters patent pertaining to telephony, was the licensor of the Pittsburg Company, and contracted, for a consideration received, that in case of any litigation involving the validity of said letters patent, or any of them, wherein the Pittsburg Company should be a defendant, the said National Improved Telephone Company should have prompt notice thereof, and should assume control of said litigation, and, at its option, be made a party thereto at its own expense; that the Pittsburg suit did involve the validity of said letters patent; that the National Improved Telephone Company was promptly notified thereof, and did assume control of the litigation, preparing an elaborate defense, and appearing therein by counsel, who were heard by the court, and that, becoming dissatisfied by the refusal of the court to go behind the decrees of other circuits in the matter of a preliminary injunction, the National Improved Telephone Company “ordered the immediate withdrawal from the court of all the evidence, instruments, and documents of every character connected with the defense,” and “immediately dismissed the counsel in said case.”

In Robbins v. Chicago, 4 Wall. 657, it is said:

“Conclusive effect of judgments respecting the same cause of action, and between the same parties, rests upon the just and expedient axiom that it is for the interest of the community that a limit should be opposed to the continuance of litigation, and that the same cause of action should not be brought twice to a final determination. Parties in that connection include all who are directly interested in the subject-matter, and who had a right to make a defense, control the proceedings, examine and cross-examine witnesses, and appeal from the judgment. Persons not having those rights substantially are regarded as strangers to the cause; but all who are directly interested in the suit, and have knowledge of its pendency, and who refuse or neglect to appear and avail themselves of those rights, are equally concluded by the proceedings.”

See, also, Chicago v. Robbins, 2 Black, 418.

To the same effect are Cromwell v. County of Sac, 94 U. S. 351; Chamberlain v. Preble, 11 Allen, 370; Tredway v. Sioux City, 39 Iowa, 663.

The rule is applied in patent cases. Robertson v. Hill, 6 Fisher, 465; Miller v. Liggett, 7 Fed. Rep. 91. 666 No authorities are cited to the contrary, but counsel have argued that the National Improved Telephone Company had a right to withdraw from the litigation, and that thereupon, in some unaccountable way, the company was released from all responsibility, and that the complainant had no right to proceed to a decree. We cannot avoid the conclusion that so far as the National Improved Telephone Company is concerned in this suit, that it is bound and concluded by the final decree rendered at Pittsburg, and that that decree alone warrants the injunction pendente lite in this case, as against said telephone company and its privies.

But since we have had the cause so exhaustively presented, and we have so fully considered it, we have determined not to rest our conclusions upon the decrees in the other circuits, sufficient as we deem those to be, but to examine the questions de novo.

It is urged by the defense that there should be given a weight to the fact that the executive department of the government has directed the institution of a suit to annul this patent that should lead us to refuse or defer any affirmation of the patentee's rights till the conclusion of that suit. To this we cannot assent. The executive department has not in this case attempted to adjudicate rights, nor could it in any case do more than start the judicial inquiry, and present the cause to the courts. The filing of an information cannot create a presumption of guilt. No more can the institution of a suit to annul, create a presumption of nullity. If any effect is to be given to the pendency of this suit to annul, so as to suspend any rights of the patentee, it could only result from restraining or other orders issued in that suit, where the court having the parties and the evidence upon which the nullity is sought to be established before it, has also the authority, if to annul, then to suspend the force of the patent. There is a class of cases where the decision of the executive is conclusive upon the courts. This class includes those which present political questions,—such as which is the lawful government in a state or in a foreign country,—questions connected with functions of sovereignty, where promptness and unity of action in all the departments of government are essential. All questions properly judicial are, by the very constitution, embraced within the judicial power, and submitted exclusively to the courts.

It is necessary to consider two grounds of the invalidity of the letters patent of Alexander Graham Bell, No. 174,465, issued March 7, 1876, on application filed February 14, 1876.

1. It is urged that after the filing of Bell's application his specifications and claim were changed in consequence of information derived through the examiner of the patent-office from the caveat of Elisha Gray, filed on the same day with Bell's application. We have reached the conclusion that the invention is set forth in the claim and specifications as originally filed, and that, therefore, any inquiry into this 667question would lead to nothing which could affect the validity of the patent. It is overwhelmingly established that Bell made the affidavit to his claim and specifications as originally filed on the twentieth day of January, and that Gray's description of his invention embodied in his caveat was not written out till three or four days prior to February 14th, when it was filed.

The fifth claim of Bell, originally filed, is as follows:

“(5) The method of, and apparatus for, transmitting vocal or other sounds telegraphically, as herein described, by causing electrical undulations similar in form to the vibrations of the air accompanying the said vocal or other sounds, substantially as set forth.”

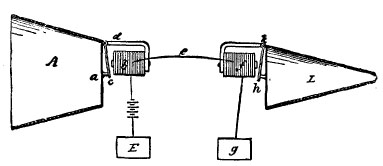

In the specifications originally filed by Bell there is the following figure and description and illustration of the apparatus and process.

Another mode is shown in Fig. 7, whereby motion can be imparted to the armature by the human voice, or by means of a musical instrument. The armature, c, Fig. 7, is fastened loosely by one extremity to the uncovered leg, d, of the electro-magnet, b, and its other extremity is attached to the center of a stretched membrane, a. A cone, A, is used to converge sound vibrations upon the membrane. When a sound is uttered in the cone, the membrane, a, is set in vibration, the armature, c, is forced to partake of the motion, and thus electrical undulations are created upon the circuit, E, b, c, f, g. These undulations are similar in form to the air vibrations caused by the sound; that is, they are represented graphically by similar curves. The undulatory current passing through the electro-magnet, f, influences its armature, h, to copy the motion of the armature, c. A similar sound to that uttered into A is then heard to proceed from L.

To simplify: In the fifth claim, and the part of the specification quoted above, the applicant declares that his invention consists in this: In the discovery that vocal or other sounds, by being uttered or otherwise communicated through a receiver, and by reason of their force being made to impinge upon an armature, impart to it the vibrations of the air; that these motions of the armature cause corresponding 668undulations in the electrical current, so that at the end of the circuit similar vibrations are given to another armature, through it to the surrounding air, and through the air to the human ear. Thus, voice is communicated to the electrical current, and reproduced at the end of the wire in the air, and all this by reason of the discovered fact that vibrations in the air caused by sound are so similar to the undulations in the electrical current that vocal sound, of whatever character itself, may be passed from air to the electrical current, and delivered again through the air, by means of a receiving and a delivering or emitting armature. The great discovered fact was that the vibrations in the air are similar in form to the following, and imparted electrical undulations, and that the undulations are similar to the ultimate vibrations. It follows that as are the vibrations so are the undulations; whether gradual or sudden; of whatever pitch or loudness; whether constant, or varying in pitch or loudness; whether caused by a single or by successive sounds.

We think this a sufficient description of the process and apparatus, and of the whole discovery patented, and that it neither required nor did it receive any substantial changes by the amendments subsequently made, no matter from what source suggested or derived.

Another objection urged by the defense was that the apparatus described in the specifications, and illustrated by Fig. 7, is not capable of transmitting articulate speech. There are affidavits to this effect, but the affidavits in favor of the capability are very strong and satisfactory, and the court itself, through its own senses, was convinced that the transmission of speech had been completely attained by means of the Bell apparatus, as exhibited by Fig. No. 7.

The fact that Bell's invention certainly dates from January 20, 1876, and that it covers a speaking telephone, transmitting articulate speech, by means of an undulatory, oscillatory, or vibratory current of electricity, renders it unnecessary to pass upon the evidence relating to the tergiversations and claims of Gray; the alleged frauds of Bell in advancing his application for a patent; the illegal conduct and “conflicting statements of Examiner Wilbur; and many alleged vices and irregularities,—the evidence of which forms the bulk of the record, and apparently the main defense in the case. At the same time, it is proper to say that in all the evidence we have found nothing that shows that Bell has done, or caused to be done, anything inconsistent with his right to be called an honest man, with clean hands. If he availed himself of information derived from Wilbur as to the contents of Gray's caveat, filed on the same day as his (Bell's) application, (which, however, does not appear,) he had a right to do so, to enable him to restrict and limit and clearly define his application, as the information shown to have been furnished was furnished under the authority of rule 33 of the patent-office for such purpose. 669 We will next consider the second ground of defense, which is that the invention of Bell lacked novelty, because it had been anticipated by Philip Reiss. That Reiss made great strides towards the discovery of the great fact or law subsequently announced in the fifth claim of Bell does not admit of doubt. That he failed to reach it is equally beyond question. Reiss discovered that, by means of the electrical current, sound could be received, transmitted, and delivered. But it was the pitch of tones that was transmitted, and exclusively by means of an intermittent make and break current,—a current incapable of conveying the form of sounds,—protracted or varying sounds,—and therefore incapacitated to convey articulate speech. His apparatus appears to have been devised in the attempt to transmit speech by electricity, but the attempt was an acknowledged failure. His apparatus, under the influence of the voice or other sounds, simply broke the circuit at each principal vibration with a frequency corresponding to the pitch of the sounds. Prof. Trowbridge says:

“It is impossible to transmit speech electrically by means of that operation, for the reproduction of articulation requires the reproduction, not merely of the number of sonorous vibrations, but what is technically known as their form or character. The electrical changes on the line wire which are to convey this characteristic from the transmitter to the receiver cannot do that unless they take note of that characteristic and bear its impress. This is as certain as any elementary proposition of geometry.”

Reiss apparently had no idea of operating through a continuous, uninterrupted current, which should be undulatory, i. e., should be plastic, impressible, and should be the medium of receiving freely and continuously, and reproducing exactly, the vibrations in the air, accompanying sound by the corresponding disturbances in the electrical current without any intermission of the flowing of the current. In the Jahresbericht, or the Annual Report of the Physical Society of Frankfort, for the year 1860-61, is an account given by Reiss himself of his invention and apparatus. It was presented to the court as translated in the biographical sketch of Philip Reiss by Silvanus P. Thompson, published in London in 1883. Upon a suggestion that the translation might be imperfect, we ordered that the memoir should be obtained from the congressional library, and should be translated into English by J. Hanno Deiler, professor of German in the Tulane University. We have carefully compared Mr. Reiss' description of his invention and apparatus as given in the two translations. While differing in the words used in the two renderings, they agree in making Reiss state that he uses an “intermittent current,” and that “each sound wave effects an opening and closing of the current.” This is made even more palpable by his illustration of his apparatus or instrument. This is entirely inconsistent with any idea of a continuing current which should undulate, i. e., be increased or diminished merely 670by an apparatus so constructed as to be susceptible of being set in motion by the vibrations of the air produced by sound; and should freely receive, convey, and deliver single or successive sounds by reason of being so constructed as to be capable of being started and continued in motion just so long as the vibrations of the air lasted. He did not apply to his instrument the law-indeed, he seems not to have designed his instrument with any reference to the law-that the vibrations in one medium had an exact correspondence to the undulations in the other, not only for an instant, but for any period of time.

The merit, and, as we think, the originality, of the Bell invention consisted in the discovery of this law, and in the construction of his apparatus so that when the sound caused aerial movements or vibrations they might, without any intermission of the current, be freely transferred or translated into electrical undulations, which again, at the end of the circuit, would freely reproduce the aerial vibrations, and thus convey, single or combined, transmitted sounds to the ear, and continue to convey them without interruption as originally uttered, whether single, combined, or successive. Reiss' result was that sound could be sent through the electric current like a missile through the air; Bell's result was that the electric current was a continuing connection between voice and ear, like the air itself.

A great fact in proof of the correctness of this deduction is that the instruments invented by Reiss, and his methods, were described in many scientific papers and works, and were well known in the scientific world; and the instruments were manufactured and on sale in Paris, Vienna, and Frankfort, and had been exhibited before the British Association, and a pair were deposited in the Smithsonian Institution; and yet before 1876 there was no speaking telephone in use, nor any pretense of any. The various reproductions of Reiss, and his methods, all were based upon the same defective electrical means, an intermittent circuit-breaking current,—and all were practical failures for the transmission of speech until Bell's method was discovered.

From the evidence submitted in this case it seems clear that now, in the present state of the art, neither the Reiss instruments, nor any reproduction of them, can be made to transmit articulate speech, except by changes of some form in the instruments themselves, or by the employment of Bell's method. We therefore conclude that neither Reiss nor his successors anticipated the invention of Bell, as set forth in the fifth claim of his application and patent, and as illustrated by Fig. 7, described in his accompanying specification.

The Mencci defense that is brought forward in defendants' record, on this motion, taking up 120 printed pages, was abandoned by counsel on the hearing, and no effort made to sustain it.

There remains, therefore, but the question of infringement. This matter has not been squarely met by the defendants. The complainants' 671bill alleges, and their experts testify in the opening papers, that the instruments used by the defendants consist of a microphone transmitter and a magneto receiver, which has been decided in the Spencer and Molecular Cases to be an infringement. The defendants in their answer, (unsworn to,) in a vague and argumentative way, deny infringement. In their affidavits they do not attempt to show what they were using at the filing of the bill; but they allege, in affidavits filed pending this motion, that “defendants' apparatus, as now used, may be more particularly defined as operating in method or principle of operation under the Reiss inventions of 1860-64, and under special inventions patented by Randall, May 21, 1878; May 4, 1880; and May 3, 1881.” Complainants having filed affidavits showing infringements in this apparatus now used, leave was granted to defendants to file another affidavit, stating fully what it is that defendants use. Under this leave an affidavit of C. A. Randall (the sixth in the record) has been filed, which contains much impertinent matter reflecting on counsel and opposing experts, but throws no direct light upon the question. But from the affiant's argument we infer that he means to say that defendants are using the apparatus above referred to. The complainants urge, and their affidavits show, that the instruments of the Randall patents above referred to transmit speech by means of the Bell variations of current, and we are disposed to agree with them in this view.

Let the injunction issue.

1 Reported by Joseph P. Hornor, Esq., of the New Orleansbar.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.