846

THE ALHAMBRA.1

THE RHODE ISLAND.

PROVIDENCE & STONINGTON STEAM-SHIP CO. v. THE ALHAMBRA.

QUEBEC STEAM-SHIP Co. v. THE RHODE ISLAND.

District Court, S. D. New York.

December 9, 1885.

v.25F, no.14-54

COLLISION—TWO STEAMERS—SUDDEN SHEAR—CONFLICTING EVIDENCE AS TO LIGHTS AND BEARINGS CONSIDERED—NARRATIVE.

On the night of July 18, 1882, a collision occurred in the Sound between the steamer A. and the steam-boat R. I., the weather being clear, and both vessels seeing each other's lights at a great distance. The A.'s account of the collision was that while making a course E. by N., she sighted both the colored lights of the R. I. about three-fourths of a point on her starboard bow, several miles distant. That thereafter the red light of the R. I. was shut in, and her green light gradually drew to three or four points off the A.'s starboard bow, both vessels showing green to green, up to within a minute of the collision, when the R. I. took a sheer to cross the bows of the A., which at once stopped and backed, but was unable to avoid a collision. The account given by the R. I. was that while heading W. ½ S. she saw the mast-head light of the A. a little on her port bow, and about four miles distant; that, shortly after, the red light of the A. came into view three-fourths of a point on her port bow, when the R. I.'s wheel was ported, and one whistle given, and her course changed to W. 1/8 N.; that she continued on that course, the A.'s red light being always on her port bow, and not observed to change much, till suddenly the A. was seen close at hand on the port beam, with her green light exposed; that the wheel of the R. I. was put hard a-port, but the collision followed immediately. Held, that these two narratives were irreconcilable; that whichever story be correct, it must be found to be in the main consistent with itself and with the undoubted courses of the steamers, which must be assumed to be as sworn to by each, up to within a few minutes of the collision; that an examination of the testimony of each, with a diagram of the respective courses, positions, and bearings showed that the A.'s account was consistent and credible, and the account of the R. I. inconsistent with itself, and irreconcilable with the undoubted previous courses of each; that the sudden sheer just before the collision was made by the R. I., and was probably due to the fact, disclosed in the testimony of the pilot of the R. I., that he supposed the A.'s lights were the lights of a tow; that the A. did all that was possible to avoid the collision, and the libel against her should consequently be dismissed, and the suit against the R. I. sustained.

847

In Admiralty.

Miller, Peckham & Dixon, for the Rhode Island.

Butler, Stillman & Hubbard and Wm. Mynderse, for the Alhambra.

BROWN, J. The above cross-libels were filed by the owners of the steamers Rhode Island and Alhambra to recover their respective damages arising out of a collision that occurred between those vessels about 2 A. M. on the night of July 18, 1882, on Long Island sound about opposite New Haven. The alleged damages to the Rhode Island amounted to $40,000; those of the Alhambra to $25,000.

The Rhode Island was a new, side-wheel steamer, 344 feet long, built in 1881, and running regularly between New York and Providence, making usually from 14 to 15 knots per hour. The Alhambra was a smaller iron screw-propeller, of about 740 tons register, bound from New York to Halifax, and running at eight and one-half to nine knots per hour. The night had been foggy earlier in the evening, but had cleared up some hours before the collision; and at that time the weather was clear and good for seeing lights; the water was smooth, and the wind light. The Rhode Island was bound west towards New York, following her usual course. The Alhambra, going east, had passed the Stratford Shoal (or Middle Ground) light at 12:40 A. M. The statement of her witnesses is that as she was making a course of E. by N., or E. ¾ N., magnetic, at 1:46 she sighted the white mast-head light and the two colored lights of the Rhode Island, about three-fourths of a point on her starboard bow; that these three lights continued from one to two minutes nearly on the same bearing, when the Rhode Island's red light was shut in and her green light only was seen; that the Alhambra thereupon, to give more room, starboarded her wheel, so as to bring her course half a point more to the northward, viz., to E. by N. ½ N., and then steadied; that she continued on this course for several minutes, the Rhode Island's green light all the time broadening on her starboard bow, until suddenly the Rhode Island was seen to shut in her green light, and to show her red light, and all the cabin lights along her port side, at which time she gave one blast of the whistle; that on seeing the red light again, the Alhambra ordered her engines reversed, full speed, answered with one whistle, and as soon as possible put the helm hard a-starboard to assist the back action of the propeller in turning her head to starboard; that these whistles were about one minute before the collision; and that the engine was reversed and got about four revolutions backwards when the collision occurred, at 2:03 A. M., by the Alhambra's stem striking the port side of the Rhode Island at nearly right angles, a little abaft of the center of the paddle-box.

By this account the steamers while approaching each other showed green to green, for some four or five minutes, up to within a minute of the collision, when the Rhode Island took a rapid sheer to northward 848across the bows of the Alhambra, rendering the collision inevitable. This account is substantiated, in the main, by the pilot, the quartermaster, and the lookout, and by another witness who was in the pilot-house observing the courses and lights preparatory to taking charge of the ship.

The Rhode Island's account, as given by the pilot and quartermaster, is that while proceeding on her usual course of W. ½ S., magnetic, and heading, as usual, exactly for Stratford Shoal light, and shortly after making that light dead ahead, the white mast-head light of the Alhambra was seen about one-half or three-fourths of a point on their port bow, estimated to be four miles distant; that, with the glasses, her red light was seen on the same bearing; that a few minutes afterwards the red light came in sight to the naked eye, estimated to be three miles distant, when it was reported by the lookout and seen by the pilot three-fourths of a point on their port bow; that the pilot at once thereupon blew one blast of the whistle, which was immediately answered with one from the Alhambra, and that the Rhode Island's wheel was at once ported so as to put her ahead five-eighths of a point to the northward, upon a course of W. 1/8 N., magnetic; that she continued upon that course, the Alhambra's red light being always on her port bow, and not changing its position much, until suddenly the Alhambra was seen on the port beam, not over one-quarter of a mile distant, her red light shut in and her green light exposed; that the Rhode Island's helm was at once put hard a-port; that her wheel is moved by steam, and goes hard over in 12 seconds, during which time the steamer would swing about two and one-half points; that the collision occurred in six or eight seconds after the wheel was hard over, when she was struck nearly at right angles, as stated by the Alhambra's witnesses.

Capt. Mott testifies that he was lying down in his room near the pilot-house; that he heard the one whistle given and answered; that he heard the pilot immediately thereafter give the order to change five-eighths of a point to W. by S., (W. 1/8 N., magnetic;) that he put on his coat, vest, and shoes leisurely; heard the pilot say that “the other vessel was showing her green light,” and heard him order the helm hard a-port; and that he came into the pilot-house about the moment that the helm slid into the chock hard a-port; that he saw the Alhambra then very nearly abeam, some 300 feet only away, showing her green light only, and coming directly upon the Rhode Island, which she struck within 12 seconds afterwards. He estimates that the whistles were given about three minutes before the collision, and that there was scarcely any interval between the two whistles. According to this account the steamers were approaching each other red to red until within half a minute of the collision, when the Alhambra took a sudden sheer to the northward to cross the Rhode Island's bows, and thus caused the collision by her fault alone.

These two narratives are in painful conflict. It is evident that 849they cannot be reconciled. Not only do they conflict as to the lights visible to and from each steamer, and as to the bearings of these lights during the greater part of the interval, but also as to the time when the whistle was given and answered. I have found it impossible to make any progress in the satisfactory disposition of the cause, except upon first determining which of these opposite narratives is to be adopted as in the main correct.

As respects the time of giving the whistle the pilot of the Rhode Island has given different accounts; at one time saying it was some minutes after the Alhambra's red light became visible, but finally saying it was at the same time, viz., when the Alhambra was about three miles, i. e., about seven and one-half minutes, distant. Both he and the quartermaster say that the first change of five-eighths of a point to the northward was at the time this whistle was given; and this latter statement is in a measure supported by Capt. Mott, who says he heard that order right after the whistle; but he estimates the time of the whistle at three minutes before the collision, while the Alhambra's witnesses estimate it at from one-half minute to one and one-fourth minutes before the collision. Another circumstance in Capt. Mott's testimony not only disagrees with the estimate of his pilot, but rather confirms the Alhambra's estimate of less than three minutes. In answer to the question, “How long was it between the two whistles?” he says: “Not scarcely any; he answered right prompt.” Considering that sound travels at the rate of five seconds per mile, if the vessels were three miles apart it must have been a half minute between giving the whistle and hearing the reply, besides some additional interval always waited for by the answering vessel to listen for a second blast before replying. If the vessels were only half a mile apart, or one and one-fourth minutes, a reply would ordinarily be heard after an interval of about 10 seconds, which agrees more naturally with Capt. Mott's expression as to the Alhambra's quick reply. The time when the Rhode Island gave this whistle and made her first change of five-eighths of a point to the northward is very important in considering the bearings of the vessels' lights towards each other, and the lookout probably kept; and the discrepancy between Capt. Mott's testimony and the pilot's and quartermaster's evidence, and the variations in the latter, become a strong confirmation of the more probable correctness of the Alhambra's witnesses on this point.

It is, morever, improbable and unusual that a whistle should be given and answered at a distance of three miles; and it is a singular circumstance that the Alhambra, though said to be showing her red light about three-fourths of a point on the Rhode Island's port bow, should not have been observed to be drawing gradually more and more off the port bow, but should show no very apparent increase on that bearing until she was suddenly seen nearly abeam, coming directly upon the Rhode Island. This proves either that the apparent 850change of course by the Alhambra was not caused by her own change, but by the swinging of the Rhode Island herself; or else that no proper watch was kept of the Alhambra between the great change of her bearing from about one-half or three-fourths of a point off the Rhode Island's port bow to nearly abeam. While this alternative does not determine which vessel made the final change to the northward that caused the collision, it certainly detracts from the general credit to be given to the Rhode Island's account, from the lack of constant attention to the Alhambra which it implies.

Each steamer was in charge of competent officers, well accustomed to the route. There is no essential difference in the means of observation of the men in charge of each; yet one or the other must be mistaken, both as to the bearing and as to the color of the lights seen. The circumstances I have mentioned above are favorable to the Alhambra's account. Alone, however, they would hardly have sufficient weight to satisfy me, in a case of such importance, to adopt the account of the one and to reject that of the other. Whichever story, however, be correct, it must be found to be in the main consistent with itself, and with the undoubted courses of both steamers up to within a few minutes of the collision; and a careful examination of the narrative of each in this respect satisfies me that the Alhambra's account is consistent and credible, and the Rhode Island's account inconsistent with itself, and impossible to be reconciled with the undoubted previous courses of the two steamers.

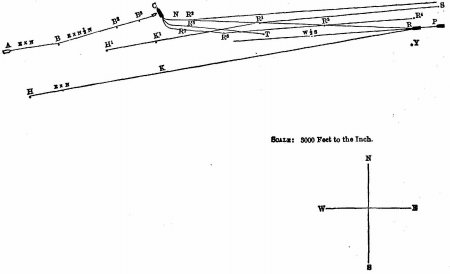

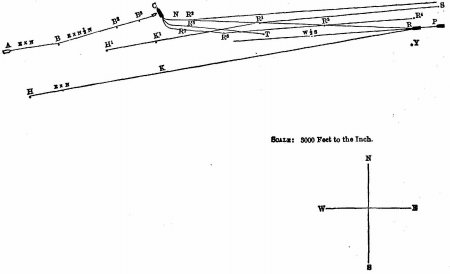

The difficulties of the case and the credibility of the two accounts cannot be fully understood and appreciated without a resort to diagrams of the courses of the vessels, and of the alleged bearings of their lights during the seven or eight minutes preceding the collision, reckoning their courses backwards from the point of collision. The courses of the vessels previous to that time cannot be fixed, with reference to any definite landmarks, with sufficient accuracy to determine which one had the line of her course to the northward of the other. The distance of Stratford light from the Alhambra as she passed it is not fixed; and the long courses of the Rhode Island are also subject to more or less accidental variations from the strict compass course.

A diagram is annexed, of which I have made use, drawn upon a scale of 750 feet to the inch, [reduced below to 3,000 feet.] As the vessels were going at the rates, respectively, of about 9 knots and 15 knots per hour, the Alhambra made about 900 feet per minute, and the Rhode Island 1,500 feet; together 2,400 feet, or at the rate of a mile in 2½ minutes. Each may have been moving a little slower, but the proportions are correct, and those rates may be assumed without any material error. As there is no reason to suppose the previous courses of each are not accurately stated, it must be assumed as true (1) that up to a short time before the collision, that is, not exceeding one or two minutes, the courses of each vessel were in the directions stated by each; (2) that each, after the other was sighted, and 851 852from two to seven minutes before the collision, made a change to the northward of about one-half a point, though the precise time, and the distance from each other when their respective changes were made, may not be accurately fixed; (3) that from half a minute to a minute and a half before the collision, another sudden change was made, by one vessel or the other, by a sharp sheer to the northward, which was followed by a collision at nearly right angles.

852from two to seven minutes before the collision, made a change to the northward of about one-half a point, though the precise time, and the distance from each other when their respective changes were made, may not be accurately fixed; (3) that from half a minute to a minute and a half before the collision, another sudden change was made, by one vessel or the other, by a sharp sheer to the northward, which was followed by a collision at nearly right angles.

Upon the diagram annexed, the lines, P, R, N, C, represent the course of the Rhode Island, as stated by her pilot and quartermaster; R represents the position of the Rhode Island when the vessels were estimated to be three miles, or seven and a half minutes, apart, viz., at the time when the pilot says he whistled, just before changing five-eighths of a point to the northward; P, R, represents her previous course of W. ½ S.; R, N, a course of five-eighths of a point more to the northward, viz., W. 1/8 N.; and N, C, the short curve during 20 or 30 seconds preceding the collision, according to the Rhode Island's own account.

If the pilot of the Rhode Island, at R, before porting saw the Alhambra's red light even one-half of a point off her port bow, the Alhambra would be somewhere on the line R, H, and within seven and one-half minutes reach of C, i. e., at H, about one and one-eighth miles from C. But if that was the actual place of the Alhambra at that time, it is manifest that the latter, heading E. by N., must have then shown both colored lights to the Rhode Island. Moreover, she could not have reached C except by changing her course at once from E. by N. some two points more to the northward; and in that case her green light would have been visible for the following seven and one-half minutes; whereas the Rhode Island's witnesses state that her green light was not visible till within less than a half minute of the collision. On the other hand, if the Alhambra had not changed her course from H at once to the northward, but continued from H upon her previous course of E. by N., or E. by N. ½ N., until within a half minute of the collision, before turning further northward, she would have been near K, more than one-third of a mile almost directly south of the place of collision, and at a point where collision with the Rhode Island, then at N, would have been impossible. If the Alhambra had been seen three-fourths of a point off the port bow, when the Rhode Island was at R, the case would be more improbable still. The statement that the Rhode Island saw the Alhambra one-half or three-fourths of a point on her port bow when 3 miles off, and before her own first change of course to W. 1/8 N., is therefore manifestly incorrect, and must be rejected.

But precisely the same result follows if any other point on the line, R, N, be taken as the place where the Rhode Island may be supposed to have seen the Alhambra, say half of a point on her port bow, just before changing her course to W. 1/8 N.; as, for instance, at R1, distant three minutes from C; her previous course being S, R1. 853The Alhambra, half a point off the Rhode Island's port bow, would then be at or near H1, on the line, R1, H1; three minutes, i. e., about 2,700 feet, distant from C. From that situation, in order to reach C, she must immediately have changed from two to three points to the north, and must in that case at once have shown her green light; or else, in continuing on her course of E. by N. ½ N., to K1, she must have gone much to the southward of the Rhode Island; and, whether approaching H or H1, she must for a considerable time have shown both colored lights to the Rhode Island, unless she had previously changed her course to E. by N. ½ N., and in that case would have shown the green light only for several minutes.

These drawings show conclusively that the Alhambra could not have been seen one-half or three-quarters of a point on the Rhode Island's port bow before she changed her course from W. ½ S. to W. 1/8 N.; because the Alhambra could not have been in that direction, and her previous course was such that she could not possibly have reached the place of collision through either H or H1, or near them, without showing her green light a long time before the half minute preceding the collision; nor unless the testimony of her own witnesses as to her previous course be wholly discredited, which is not admissible. This account given by the witnesses of the Rhode Island is, therefore, wholly irreconcilable with itself and with the prior courses of both vessels, and therefore cannot be admitted as correct.

Applying the same tests to the testimony of the Alhambra's witnesses, we have her general course leading to the place of collision from A, when three miles from R, to B, two miles distant, on a course E. by N., magnetic, and thence from B to C, one-half of a point more to the northward, viz., E. by N. ½ N., varied somewhat, possibly, in the last half minute, when near the place of collision at C.

If the Alhambra at A, as her witnesses allege, had the Rhode Island three-fourths of a point on her starboard bow, the latter would be at Y. But the Rhode Island, if then heading W. ½ S., would head to the south of the Alhambra, and show to the Alhambra her green light, and not both colored lights, as alleged; while if the Rhode Island had already changed to W. 1/8 N., she would head three-eighths of a point north of the Alhambra, and have shown the red, and not the green light. But if the Rhode Island bore only half a point, instead of three-fourths of a point, off the Alhambra's starboard bow, her two colored lights would be visible before she ported. This would place the Rhode Island at R4; and the difference between one-half and three-fourths of a point is a very slight difference to observe at night in a range over the bow. The range of one-half of a point on the Alhambra's starboard bow may therefore be provisionally adopted. If, then, the Rhode Island continued on her course W. ½ S., and the Alhambra on hers of E. by N., for two and one-half minutes, till the vessels were within two miles of each other, or five minutes apart, as her witnesses estimate, the Alhambra would be at B, where it is 854said she starboarded a half point. The Rhode Island would then be at R5, bearing five-eighths of a point off the starboard bow of the Alhambra; and though still heading W. ½ S. before she ported, she would at that point have passed enough south of the line of the Alhambra's course to shut in her own red light and show to the Alhambra her green only, as the witneses of the Alhambra all allege the fact to be. Upon the Alhambra's starboarding one-half of a point at B. as they allege she did, the Rhode Island would then bear one and one-eighth points off the Alhambra's starboard bow. Continuing, then, three minutes more on her course of E. by N. ½ N., the Alhambra would arrive at B2 two minutes before the collision; and if the Rhode Island had still continued on her previous course of W. ½ S., she would have come to R6, nearly two points on the Alhambra's starboard bow, show-to the latter always during this interval her green light only. Considering the difference between the captain and the quartermaster of the Rhode Island as to the time when her whistle was given, and when she ported five-eights of a point, the account of the Alhambra is so far not only entirely credible and consistent with itself, but also consistent with the probable course of the Rhode Island. The lights would be exhibited to each other precisely as the witnesses of the Alhambra testify, and the bearings from each other would be about as they allege. I must accept her account, therefore, up to this point, as substantially correct, only varying a little as to the estimated distance to starboard that the Rhode Island's lights bore,—a point upon which there are some differences in the testimony.

With the vessels in these positions when two minutes apart, which was the estimate at one time given by Capt. Mott as to the time when the whistle was blown, there was no reason to apprehend a collision. The steamers were showing green to green, as they had been for some minutes before; the Alhambra was bearing nearly a point on the Rhode Island's starboard bow, and the Rhode Island nearly two points off the Alhambra's starboard bow. Two minutes afterwards the collision happened at nearly right angles. It is manifest that if the positions of the two vessels two minutes before the collision were anything approaching the relative positions of B2 and R6, the fault of the collision must be charged upon the Rhode Island, in going to the northward across the line of the Alhambra's course. They showed green to green, and their courses were sufficiently diverging to require no further maneuvering to avoid each other. That the Rhode Island did go to the northward by two changes of her wheel at some time is conceded; and her last change was very shortly before the collision. Her doing so, and thus crossing the Alhambra's course, would be wholly unaccountable, and a supposition almost inadmissible, except for a single circumstance. The pilot five times in the course of his testimony states that he supposed the Alhambra's lights to be the lights of a tow, or of a tug and tow. Such tows are frequent upon these waters. If the tow extended much behind, the 855pilot may have had justifiable reason for preferring to go to the northward; and as the speed of a tow is very much slower than that of the Alhambra, the Rhode Island would have had no difficulty, had her surmise been correct, in passing the tow upon the northerly route she took; as it was, and with the Alhambra's much greater speed, 10 seconds more would have enabled her to clear the Alhambra.

I have found no other conceivable explanation of this collision, and I am satisfied it is the true one. With this explanation, the Rhode Island is necessarily found in fault.

Upon this view, the only ground upon which the Alhambra can be charged with fault is that she did not do all that was possible to her to avoid the collision when the exchange of one whistle was given. But it is impossible to fix with certainty just how long before the collision these whistles were exchanged. The quartermaster and the pilot of the Rhode Island are so clearly erroneous in their statements on this point that no reliance can be placed upon them. Nor is it possible to accept their statement that, for several minutes before the collision, the Alhambra's red light was visible off their port bow. The Alhambra could not have reached the point of collision if that were so; and the entire evidence of her witnesses would have to be discredited in every particular, even as to the previous course she was pursuing. I am entirely satisfied that it was the Alhambra's green light that was visible for several minutes; and that it was visible upon the Rhode Island's starboard bow, and not on her port bow; and on the whole evidence I think it probable that the Rhode Island's course was first changed to W. 1/8 N. about two or three minutes before the collision, say at R6 or at T; and that her helm was put hard a-port, about one minute before the collision, near R7 or R8 when the Alhambra was at B3. Capt. Mott's estimate of the interval between the whistle and the collision is but a guess; and the estimate of the Alhambra's witnesses is that it was only from half a minute to a minute and a quarter. All her witnesses agree that the engine was ordered reversed full speed at once, and that the order was promptly obeyed. I see no reason to discredit this testimony. It would take from two to three minutes to bring the Alhambra to a full stop. Her witnesses all say the whistle was not heard until just after a sudden change by the Rhode Island from showing the green light to showing the red. This agrees with their prior testimony. The drawing shows that the Rhode Island, after changing to W. 1/8 N., say at R6 or T, would still show her green light only, and would continue to do so until her second change, say at R7 or R8, about a minute before the collision. Her whistle was probably given at that time, when, supposing the Alhambra to be a tug and tow, she undertook to cross her bow by going to the northward. This made the danger of collision imminent, so that the Alhambra's reversing was not only justifiable, but obligatory under the statutory rule.856 The evidence in this case, and in other similar cases, is that upon reversal of the engines of a screw-propeller, the action of the helm is comparatively slight. Whether there was a momentary porting or not by mistake, could not, I think, have affected the result, if the whistle was given at the time the Alhambra's engine was reversed. If, on the other hand, the whistle was given earlier, porting the helm would have been a proper maneuver. But the fact that the steamers collided at nearly right angles would seem to show that the Alhambra probably had not previously changed her course at all to the southward; and the starboard wheel was a proper movement of the helm to aid the propeller, under reversed engines, to go to starboard, in accordance with the signals. The probability, however, is that the whistles were not given until from one to two minutes after the Rhode Island made her first change to W. 1/8 N., as above suggested. The testimony of the quartermaster of the Rhode Island, in answer to repeated questions of the court, that at the time of the collision the Rhode Island headed nearly to the New Haven light, which was nearly north from the place of collision, further tends to corroborate the account given by the Alhambra's witnesses, and to show that the change that brought about the collision was almost wholly, if not entirely, a change northward by the Rhode Island.

On the whole, I do not perceive any satisfactory proof of fault on the part of the Alhambra, or anything that she could have done further after the Rhode Island showed her red light that would in any probability have affected the result. The libel against the Alhambra must therefore be dismissed, with costs, and a decree entered for the libelants against the Rhode Island, with costs, and an order of reference to compute the damages.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.

852from two to seven minutes before the collision, made a change to the northward of about one-half a point, though the precise time, and the distance from each other when their respective changes were made, may not be accurately fixed; (3) that from half a minute to a minute and a half before the collision, another sudden change was made, by one vessel or the other, by a sharp sheer to the northward, which was followed by a collision at nearly right angles.

852from two to seven minutes before the collision, made a change to the northward of about one-half a point, though the precise time, and the distance from each other when their respective changes were made, may not be accurately fixed; (3) that from half a minute to a minute and a half before the collision, another sudden change was made, by one vessel or the other, by a sharp sheer to the northward, which was followed by a collision at nearly right angles.