NEW YORK BUNG & BUSHING CO. v. DOELGER.

Circuit Court, S. D. New York.

March 7, 1885.

v.23F, no.4-13

PATENTS FOR INVENTIONS—BUNGS AND BUSHINGS—REISSUE NO. 10,368—PATENT NO. 107,473.

Reissue patent No. 10,368, granted to the New York Bung & Bushing Company August 25, 1883, for an improvement in bungs and bushings, compared with patent No. 107,473, granted to Vincent Fountain, Jr., September 20, 1870, for an improvement in bungs, and held void for want of invention, and not infringed by defendant.

In Equity.

Louis W. Frost and Wyllys Hodges, for complainant.

Henry Brodhead and Philip R. Voorhees, for defendant.

COXE, J. This is an equity action for infringement, founded upon reissued letters patent No. 10,368, granted to the complainant August 19225, 1883, for an improvement in bungs and bushings. The original patent, No. 141,473, was granted to Samuel R. Thompson, August 5, 1873, for an improvement in bushings for faucet holes. It was first reissued, No. 8,483, to McKean, Jackson, and Brown, November 12, 1878. This reissue having been pronounced invalid, as containing an unlawfully expanded claim, the patent was again reissued in form substantially like the original, except that the inventor limits the construction of the bushing to wood. The second reissue is the one in controversy. The inventor declares:

“The present invention relates to certain new and useful improvements in bushings for faucet-holes of barrels, etc., having for their principal object the production of a simple, economical, and effective bushing that will admit of the easy adjustment and withdrawal of the faucet without injury to the barrel, and that may be readily and cheaply replaced when worn. My improvements consist, mainly, of a bushing of wood, etc., constructed and arranged, as will be hereinafter more fully described, so as to receive and allow of the yielding either way of a faucet, which, when slightly struck, is readily withdrawn from the bushing without detriment to the barrel. * * * In my original specification I mentioned the use of other material than wood for the bushing, a. This I desire now to disclaim, and confine my invention to wood alone, in combination with the protecting casing, b, or to the casing, a, of wood alone, when made with the interior bevels.”

The first claim of the reissue, the second of the original, is the only one in controversy, and is in these words: “The combination of a wooden bushing, a, and casing, b, constructed and arranged as described, and for the purposes specified.” In the original the word “wooden” is omitted. The defenses are want of novelty and invention, non—infringement, and invalidity of the reissue as a reissue. As bearing upon the first of these defenses, the defendant offered in evidence letters patent No. 107,473, granted to Vincent Fountain, Jr., September 20, 1870, for an improvement in bungs. The description contains these words:

“The nature of my invention consists in the construction of a bung which has an opening through its center applicable for receiving not only a faucet for drawing off the contents of a barrel, but also for a stopper, which is inserted from the inside, as will be hereafter more fully described. * * * F is a bush, of the ordinary construction. D is a bung which has an opening extending through its centre, beveled from each side towards the line, E.”

The claim is as follows:

“A bung, having an opening through its center, one side of which is applicable for receiving a cork or stopper, G, and the other for receiving a faucet, in the manner and for the purposes set forth.”

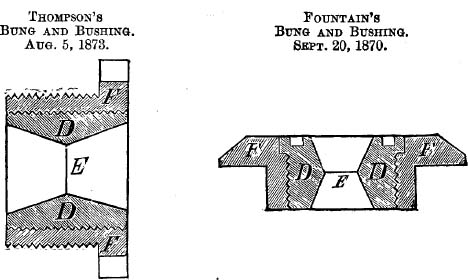

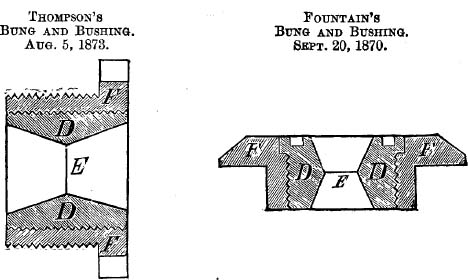

Here is a perfect description, in general terms at least, of the complainant's device, and if the word “wooden” were inserted before the word “bung,” it can hardly be doubted that it would amount to a complete anticipation. A skilled mechanic reading such description would make precisely what Thompson made. The similarity will appear most clearly by placing the two drawings in juxtaposition.

193

The same letters have been used to indicate corresponding parts on each of these drawings. D represents the double beveled bung, and F the bushing. In Fountain's specification the material of neither is designated. That this patent is an anticipation cannot be successfully maintained. But it seems equally clear that, in connection with the other proof, it defeats complainant's patent for want of invention. Thus, it must be conceded that after Fountain nothing remained upon which mechanical ingenuity could operate, except the choice of materials. If choosing wood for the bung was invention, choosing copper or brass for the bushing would be equally so. There is nothing in Fountain's patent which necessarily precludes the idea of wood being used. For aught that appears from the patent itself, wood was the very material he had in mind. If lead, or cork, or rubber had been named there would have been greater scope for the ingenuity of others. The question, then, is this: Did Thompson become an inventor because he made Fountain's bung of wood? If there were any doubt as to how this question should be answered, an examination of the proofs bearing upon the state of the art makes a negative answer alone possible. At the date of Thompson's application wooden bungs, wooden bungs with double conical holes through them, bungs inclosed in bushings, having beveled openings through the center to receive the faucet, iron bushings, and wooden plugs in iron bushings were all old. It was also well known that the elasticity of wood presented a suitable yielding bearing to hold a faucet. With the theater of invention thus crowded to its utmost capacity, with scarcely room for another actor on the stage, can it be said that he who merely suggests the change, in an old device, of one known material for another which had been previously used for kindred purposes, possesses what the supreme court defines as “that intuitive faculty of the mind put forth in the search for new results or new 194methods, creating what had not before existed, or bringing to light what lay hidden from vision?” Hollister v. Manufacturing Co. 5 Sup. Ct. Rep. 717.

The mere substitution of one known material for another has been decided over and over again to be insufficient to sustain a patent. In Hotchkiss v. Greenwood, 11 How. 248, porcelain was substituted for wood or metal in the manufacture of door-knobs. Mr. Justice NELSON, speaking for the court, says:

“Now it may very well be, that, by connecting the clay or porcelain knob with the metallic shank in this well-known mode, an article is produced better and cheaper than in the case of the metallic or wood knob; but this does not result from any new mechanical device or contrivance, but from the fact that the material of which the knob is composed happens to be better adapted to the purpose for which it is made. The improvement consists in the superiority of the material, and which is not new, over that previously employed In making the knob. But this, of itself, can never be the subject of a patent. No one will pretend that a machine made, in whole or in part, of materials better adapted to the purpose for which it is used than the materials of which he old one is constructed, and for that reason better and cheaper, can be distinguished from the old one, or, in the sense of the patent law, can entitle the manufacturer to a patent. The difference is formal, and destitute of ingenuity or invention. It may afford evidence of judgment and skill in the selection and adaptation of the materials in the manufacture of the instrument for the purposes intended, but nothing more.”

In Hicks v. Kelsey, 18 Wall. 670, the change from wood to iron in a wagon-reach; in Palmenburg v. Buchholz, 21 Blatchf. C. C. 162; S. C. 13 FED. REP. 672, the substitution of papier-mache for the wire of the frame of a lay figure; and, in a case referred to in Hotchkiss v. Greenwood, supra, “the substitution of wood for bone as the basis of a button covered with tin,” were held, respectively, to be wanting in patentable novelty. See, also, Collins Co. v. Coes, 21 FED. REP. 38; Brown v. Piper, 91 U. S. 37; Roberts v. Ryer, Id. 150; Smith v. Nichols, 21 Wall. 112; Pickering v. McCullough, 104 U. S. 310; Welling v. Crane, 14 FED. REP. 571; Walk. Pat. § 28; Sim. Pat. 31. The case of Smith v. Goodyear Dental Vulcanite Co. 93 U. S. 486, has been examined, and it is thought that it enunciates no principle in conflict with the position here taken. It must, therefore, be decided, in the language of Palmenburg v. Buchholz, supra, that, “although the device may have been mechanically new, it was not intellectually novel.”

But upon the question of infringement the difficulties which confront the complainant are almost equally as numerous and insurmountable. In the case of This Complainant v. Hoffman, 20 Blatchf. C. C. 3, S. C. 9 FED. REP. 199, this court decided, in substance, that the first reissue was void, because it sought to do precisely what complainant now seeks to do, viz., to cover broadly a hollow wooden bung inside an iron or rigid bushing. The court was unquestionably right in holding that this reissue, if valid, was infringed. To hold, however, that the defendant's device infringes the original or second reissue, 195is quite a different proposition. What the defendant uses is covered by the broad claim of the first reissue; but the court, in the Hoffman Case, decided that the patentee was not permitted to claim “any form of a wooden bushing in an iron one,” but that he must be confined to the particular form and combination described in the original patent. It was further decided that the form of the wooden bushing, or bung, with the double conical opening through the center, was “the very essence of that part of the invention,” and could not be disregarded. How, then, does the defendant infringe? His bung is not bored through; it has no bevels; it is not screwed into the iron bushing; the iron bushing has no interior screw threads, and the bung has no exterior screw threads. If the complainant had a valid claim broadly covering a hollow wooden bung inside an iron bushing, the defendant would be compelled to pay tribute; but, confining the claim within the narrow limits indicated, it must be held that he does not infringe.

The bill is dismissed.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.