McFARLAND and another v. SPENCER and another.

Circuit Court, S. D. New York.

February, 1885.

PATENTS FOR INVENTIONS—METAL TENON FOR BLIND-SLATS—PATENT NO. 76,491.

Letters patent No. 76,491, issued to William McFarland and John H. Campbell, April 7, 1868, for a metal tenon for blind-slats, held valid, and infringed by defendants.

In Equity.

Peter Van Antwerp, for complainants.

Edward S. Clinch and E. T. Rice, for defendants.

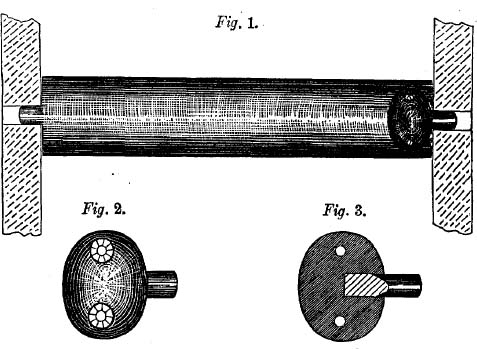

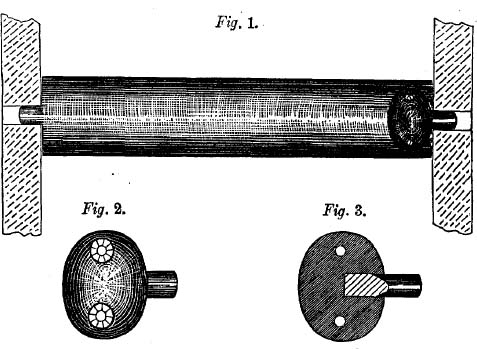

COXE, J. The complainants are the owners of letters patent No. 76,491, issued to William McFarland and John H. Campbell, April 7, 1868, for a metal tenon for blind-slats. The object of the invention is to provide tenons for blind-slats when the original tenons are broken off or injured so as to become inoperative. The following diagrams will serve to illustrate the invention:

151

Fig. 1 represents the tenon applied and fitted to a blind-slat, and working in the mortise of the frame, in place of the one broken or removed; Fig. 2, the face view of the tenon, with escutcheon plate on its inner end; Fig. 3, the same reversed, showing the connection of the escutcheon plate to the tenon by means of a beveled shoulder. The inventor declares in the specification that “heretofore the breaking off or the decay of a tenon has caused the entire loss of the slat, there being no means or device known, previous to my invention, whereby the tenon could be restored or repaired without incurring too much expense; and furthermore, the repair or restoration of a broken tenon is difficult without the removal of one of the side-bars of the frame.” The advantages of the invention are economy, simplicity, symmetry, and durability. It is much cheaper to use the metal tenon than to remove the slat. A person possessed of a pocket-knife and a very limited amount of mechanical skill can make the repair. Prior to the invention it was necessary to take down the blind, separate the frame, remove the broken slat, substitute the new slat, attach it to the hand-rod Which operates the series of slats, and readjust the frame. All this required time and skill, was expensive and inconvenient, and when the work was done it was found almost impossible to make the new slat correspond in color with the old ones. The device is an exceedingly simple and unpretending one,—so simple that, to one who sees it now, the wonder is that it did not occur to some one long before the date of the patent. But it never did. Criticism that an invention is so plain that it must be perceived by all, comes with poor grace from those who did not themselves perceive it.152 The answer is confined to specific denials of the allegations of the complaint; no affirmative defense is pleaded. The defendants introduced in evidence a patent granted to George R. Clark, March 5, 1867, for an “improved metallic blind-slat, clasp, and pivot.” It consists of a metal cap, carrying a tenon, which fits on the end of the slat. The merits claimed for it are that it prevents longitudinal splitting, and furnishes a pivot of great durability for the slat to turn on. Should a tenon become broken, the frame must necessarily be dismembered, precisely as in the case of the wooden tenon, in order to repair it. The Clark device is wholly dissimilar from that of the complainants. The defendants also, under objection, introduced testimony showing that in 1837 or 1838, 200 tenons were made, to fill a special order, out of 16-gauge strap-iron, the strap being bent so as to grasp the slat on both sides, and a pivot to swivel the slat being riveted to the bent end. These tenons could not be used for purposes of repair, except by taking the frame apart. It required mechanical skill to apply them, and they could be made only on special order, as it was necessary that they should exactly fit the slat. The defendants also proved that between 1849 and 1851 the iron shutter of a building on Reade street, New York, was repaired with a tenon like the complainants'; also that in 1844 and 1846, in Germany, similar tenons were used in the original construction of iron shutters, and that for 300 years shutters so made had been used in the tower of the church at Wittemberg, to the front door of which Martin Luther nailed his theses. It will be—seen that even had the defendants pleaded prior use, as required by section 4920 of the Revised Statutes, there is nothing in this testimony which anticipates the complainants' invention. There is no allegation that the inventor or other persons here had knowledge of the alleged prior use in Germany; but in any view the evidence is wholly inadequate to defeat the patent. As showing the state of the art, the testimony, though involved in obscurity and doubt, may be admissible, and, were the question one of infringement, such proof might require the narrow construction of a broad claim; but it is obvious that it cannot avail the defendants where they deal in the identical contrivance covered by the patent. No one, so far as the record shows, ever used, prior to the patent, a tenon like the complainants,' on wooden blind-slats, for the purposes of repair. This is what the invention covers.

There should be a decree for the complainants for an injunction and an account, with costs.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.