THE PILOT.

District Court, E. D. Virginia.

June 30, 1884.

v.20, no.13-55

COLLISION—PILOT-BOATS—STEAMER—SCHOONER—BRIG—FAULT.

Two pilot-boats, one of them a steamer, the other a sailing schooner, make for a ship, coming from sea into the capes of Chesapeake bay, to offer pilot service. The schooner crosses the bow of the ship, and meets her on the leeward, approaching within 50 feet of her. The pilot steamer approaches the ship on the windward, and, when within 300 feet, passes off by the ship's stern. In less than half a minute after the ship passes from between the two pilot vessels they collide. The schooner is damaged and sunk, and libels the steamer. Held, that each of the pilot vessels had a right to approach the ship in open sea, for the purpose of proffering pilot service, as these vessels had done, and that the steamer was not in fault in being where she was in lawful pursuit of her calling. Held, on all the proofs in the cause, that the collision which oc-cured was not by fault of the pilot steamer; and this the more true, as the schooner, when the collision was seen to be almost inevitable, made a maneuver which was the direct cause of it, and which rendered it absolutely inevitable.

In Admiralty, on a Libel for Collision.

Sharp & Hughes, for libelants.

W. Pinckney White and Floyd, Hughes, for respondents.

HUGHES, J. The licensed pilots of Chesapeake bay and Hampton roads are a high grade of seamen, having duties and powers of great responsibility. They are relied upon for the safety of many lives and much property. A court is naturally disposed, not only to give credence to the statements of such a class of officers made on oath for its information, but to place great reliance upon them. Yet I find the evidence in this case, which is almost exclusively that of pilots, exceptionally contradictory, conflicting, confusing, and inaccurate

861I think that taken by libelants much more so, in the main, than that taken by the respondents.

Many of the statements of witnesses have to be rejected outright. It is not my duty—I cannot be expected—to go through this testimony in an effort to separate what is obviously incredible from what may be credible. I have no talisman by which to perform this task with any promise of success. I must grope my way to a decision of this case under the disadvantages imposed by a mass of conflicting and inconclusive testimony.

On the third of July, one year ago, a brigantine was making in from the ocean, in broad day, to enter the capes of the Chesapeake. She was on a course W. by S. The wind was a good breeze from S. S. E. The two pilot-boats Graves and Pilot made towards her to offer pilot service. The Graves was a schooner of 75 tons, 80 feet in length. The Pilot was a steamer of 189 tons, 120 feet long. Before moving for the brig they were both in the vicinity of Cape Henry. The brigantine's course lay a little south of buoy No. 2, which is about five miles from Cape Henry. The brig, when the two pilot-boats began to make towards her, was about four miles to the eastward of the buoy. The Graves crossed the course of the brig ahead of her, and got to her leeward, and was meeting her, moving nearly on a parallel line with her. She spoke the brig when about 50 feet to the leeward. This was half a mile south-eastward of buoy No. 2. Finding that the brig did not need a pilot, the Graves passed on, moving at the rate of nine miles an hour, on a starboard tack, close-hauled, with her helm slightly a-starboard, and nearly midships. Before the Pilot (steamer) had got near the brig on the windward side, after coming up on nearly a northward course from the direction of Cape Henry, the Pilot ported her helm to pass towards the stern of the brig, and was on a N. N. E. course, with helm ported, when she had come to a distance of 300 feet from the brig. This was about the moment when the Graves spoke the brig on the opposite side. The Pilot was then moving with helm a-port at the rate of about six and a half miles an hour, her course gadually changing more and more to the eastward, under the influence of her ported helm. Finding that the Graves had spoken the brig, the Pilot intended coming round to return to her cruising-ground near Cape Henry. That was also the intention of the Graves. This intention was legitimate in each one of the two boats.

Here I will pause to remark that it is idle to contend that, while the Graves was near the brig on the opposite side, the Pilot had no right to be at a position 300 feet south of the brig. She was offering a pilot service to the brig. That was the business she was on. She had a right to be within 300 feet or 50 feet of the brig. She had the right to be as near on one side of the brig as the Graves had a right to be on the other, in an open sea. And each had the right, after leaving the brig, to make its way back to its usual cruising 862 ground in the manner most convenient to itself; the Pilot keeping out of the schooner's way.

It is true that a steamer must not only keep out of the way of a sailing vessel, but must also avoid bringing about such a conjunction of circumstances as tends to produce collision with her. The Carroll, 8 Wall. 302. And if the Graves, the Pilot, and the brig had been in a cul de sac of navigation, in which there was probable or imminent danger of collision, then the Pilot ought to have taken care not to go into it herself, even though, by keeping away, she relinquished her right to speak the brig. But there was no cul de sac in the vicinity of the collision in this case. The occurrences of the occasion all took place on the Atlantic ocean, where each pilot-boat was at full, unrestricted, and equal liberty to exercise its vocation of approaching, hailing, and Speaking ships of commerce in proffer of pilot service.

In the case under consideration, neither pilot-boat had any apprehension, or ground for apprehension, of a collision with the other, up to half a minute before the contact; and there was no probable danger of such a casualty. There was no ill-will. The testimony all shows that there was most excellent good feeling between these pilots. Whatever untoward casualty was about to occur would not occur through design. There was no malice in any breast. Any injury that should be sustained or inflicted would be the result of accident. There might be fault,—either fault in fact or fault in law; but, nevertheless, whatever should happen would be unintentional and accidental. As to what each pilot-boat thought the other was going to do, it may be said that, while custom cannot be allowed to excuse fault, if committed in violation of any one of the statutory rules of navigation, yet that one pilot-boat, coming up to speak a vessel on one side, may naturally entertain some definite idea, founded on what pilot-boats usually do on such occasions, as to what another pilot-boat, coming up to speak the same vessel on the other side, will do after speaking. When each of two pilot-boats approaches a vessel to speak her, on opposite sides, each knowing that the other is on the other side of the spoken ship, I think it is natural for each one to presume that the other, after speaking, will remain for a little while on her own side of the spoken vessel, unless some vis major or other cogent circumstance prevents. This is, of course, not a law of navigation. This cannot be declared a custom of pilots. But I think I can at least assert that the entertaining of such an idea is too natural and sensible to be declared a fault, if a steamer be so unlucky as to be the possessor of it. In the case under consideration the Pilot did presume that the Graves would keep, for at least a brief period, to the leeward of the brig and of its wake.

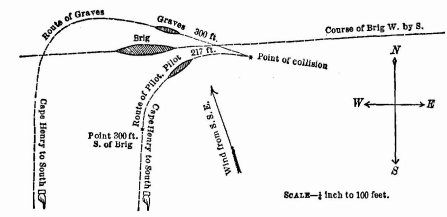

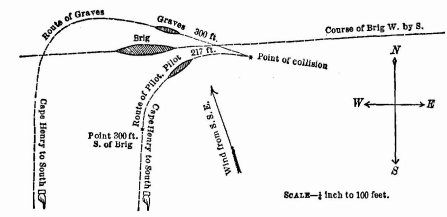

We come now to consider what did happen. The brig was a larger and taller vessel than the Graves, and than the Pilot. She was under sail; I presume under full sail. I have a right to believe that the 863 brig and her sails were opaque, and not transparent. Some of the witnesses Bay that before the pilot-boats had cleared the stern of the brig, they on one pilot-boat saw what was doing on the other pilot-boat, on the opposite side of the brig. But this implies that the brig, her rigging, and sails were transparent I feel at liberty to disbelieve all testimony implying that the brig, her sails, and rigging were transparent. I shall assume as a fact that the two pilot-boats could not see each other over the tall hulk and through the stretched sails of the brig, and that they were ignorant of everything respecting each other, except that they were on opposite sides, until the moment when the brig shot from between them. The sudden finding themselves in close proximity to each other at that moment was obviously a surprise to both. Just before this event, the two pilot-boats were running at the rate—the Graves of 9 miles an hour, or 789 feet a minute, and the Pilot of 6½ miles an hour, or 572 feet a minute. The testimony establishes that the Graves, after passing the brig for a distance of 300 feet, came in collision with the Pilot, striking her on her port bow; that is to say, they came into collision in a little more than a third of a minute (about eleven twenty-ninths of a minute) after the Graves had cleared the stern of the brig. Of course there was no possibility of effecting very much by maneuvering the two vessels in so brief an interval. The Pilot, moving slowly, and yet reaching the point of collision at the same instant when the Graves, moving rapidly in comparison, reached it, was ahead of the Graves at the moment that the Graves cleared the brig. Calculation shows that at this moment, when the Graves was 300 feet from, the point of collision, the Pilot was 217 feet, or 83 feet ahead of the Graves. The Pilot, 120 feet in length, was ahead of the Graves, 80 feet long, by more than the length of the Graves, and by within 33 feet of her own length. This fact constituted the difficulty of the situation, existing, as it did, in connection with the fact that the foremost vessel was moving more slowly than the hindmost. If either of the two facts had not existed, there could have been no collision.

Both vessels seem to have realized that the Pilot was smartly ahead. Finding herself ahead, the Pilot did all that could be done; she rang bells to increase her speed, and did increase it. Being ahead, and moving with helm a-port, the Graves being on her port quarter, the Pilot could do nothing else, in the line of her duty to keep out of the way of the Graves, but increase her speed. She did that, and would most probably have got out of the way of the Graves if the latter had kept on her course, and had made no maneuver at all. But at the critical moment, most unfortunately, the Graves hard starboarded her helm, and let fly her mainsail; thus changing her course, increasing her speed, and throwing herself upon the port-bow of the Pilot. The Pilot was moving towards the wake of the 864 brig, on a course more or less eastward of its former course; I judge about N. E. at the time of the collision. The Graves was moving, close-hauled on a starboard tack, on a course nearly due east. These courses were, of course, converging lines, and the Pilot being ahead, would, in all probability, have passed beyond the touch of the Graves, (being the length of the Graves ahead of her,) if the Graves had held her course, with rudder amidships, and having the Pilot a-port. But instead of taking the chances of passing to the rear of the Pilot, the Graves, as already said, changed her course by hard starboarding her helm, and increased her speed on the new course by letting fly her mainsail, thus putting the Pilot on her starboard bow, in which position (the Graves moving faster than the Pilot) a collision was inevitable. It was the Graves that ran into the Pilot; and the damage which she received showed that her speed was much greater than the Pilot's. Libelants contend that the Pilot should have stopped and backed. This, even if practicable in one-third of a minute, would only have rendered the shock more severe,—so severe that the Graves would have gone incontinently to the bottom.

It is clear that the immediate and direct cause of this collision was the action of the Graves in hard starboarding her helm, and letting fly her mainsail. The rule of navigation commands the sail-vessel, when in danger of colliding with a steamer, to keep on in her course and to make no maneuver at all. This is a corollary and counterpart of the rule imposing upon the steamer the duty of keeping out of the sail-vessel's way. In the present case, therefore, inasmuch as the Graves did not observe her duty, the steamer is without blame, unless it can be shown that the steamer was in fault in the fact of being at the place of collision.

This consideration renders it important to determine the point at which the collision occurred. Indeed, the present case rests in great degree on this pivotal fact. I think the conclusion is undeniable that the point of collision was about 20 feet to the south, or windward of the wake of the brig; and, as before stated, at the distance of 300 feet from the point where the Graves cleared the stern of the brig. These facts seem to be conceded by counsel on both sides.

If the collision occurred at the point thus ascertained, two other facts are thereby established, namely: First, that the Pilot had remained on her own side of the brig and of the brig's wake, not crossing over to the schooner's side; and, second, that the schooner had not remained on her side of the brig and its wake, but had crossed over to the Pilot's side. These two facts, taken in connection with the others already stated,—namely, that it was the schooner which ran into the Pilot; that the Pilot was ahead of the schooner at the time, mending her speed to get further out of the way; and that the collision was directly caused by an unfortunate maneuver of the schooner,—would seem to settle this case adversely to the Graves.

The following diagram explains my view of the matter:

865

I have not mentioned the circumstance, testified to by so many of the witnesses, that the Graves, after clearing the brig, fell off a hundred feet to leeward. In order for her to have done so, she must first have passed 120 or more feet to windward in order to have been at the point of collision when it happened. Counsel for libelants were estopped by their testimony from questioning this fact, and counsel for the respondents insist that it proves that the Graves luffed around the stern of the brig on a port helm in clearing the brig. If there was this crazy rounding to the windward, and then falling off to the leeward, by the Graves, the case is very heavily against her. I have not thought it necessary to rely at all upon this feature of the evidence. I have preferred to take no account of any of the evidence given to the effect that the Graves ported her helm at the moment of clearing the brig. I have been willing to accept, in favor of libelants, two propositions much contested by counsel: First, that the Graves was moving on an E. ½ N. course; and, second, that the Pilot was moving on a course not varying much from N. E.1 These courses would necessarily bring them into collision if they should arrive at the point of intersection at the same time. The Pilot being nearer the point of intersection of the two courses than the Graves, moving still on a port helm, with quickened speed, would, I think, have cleared the Graves, if the Graves would have allowed her to do so, by holding steadily in her own course; but the Graves, instead, made the fatal maneuver described just at the moment to render the collision inevitable. The accident was caused by this maneuver. It was caused by the Graves. The maneuver was made in violation of the twenty-third rule of navigation. The Graves was at the point of collision on the windward of the brig's wake by no fault of the steamer. The steamer, before the brig passed from between the two, was not bound to cross 866 the wake to leeward, or to keep away from those waters, or to abandon the vicinity of the place of the collision. She was where she was by right.

Decree must be for the respondents.

1 The Pilot's helm being a-port, I think she may have come around far enough towards east to have kept clear of the wake. But, for argument's sake, I disregard this probability.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Lessig's Tweeps.