78

CRŒSUS MINING, MILLING & SMELTING CO. v. COLORADO LAND & MINERAL CO.1

Circuit Court, D. Colorado.

January, 1884.

v.19, no.2-6

1. LOCATION OF MINING CLAIM—END STAKES.

The statute of Colorado (Rev. St. 630) affords no support to one who, in locating his claim, fails to set the proper stakes at the end of the claim, when the proper position for them was not inaccessible, but merely difficult of access, or approachable by a circuitous route. In such case the title will only relate to the time when the stakes are subsequently set.

2. SAME—CHANGE OF LINES.

The locator of a mining claim cannot, after the location, change the lines of his claim so as to take in other ground, when such change will interfere with the previously-accrued rights of others.

3. ACTION FOR REALTY—DEFENSE.

A defendant in an action for the possession of real estate, when he claims only a part of the tract sued for, must show what part he claims.

4. ALIEN—RIGHT TO LOCATE MINING CLAIM.

Upon declaring his intention to become a citizen, an alien may have advantage of work previously done, and of a record previously made by him in locating a mining claim on the public mineral lands.

5. SAME—STATE COURT MAY NATURALIZE.

The necessary oath declaratory of intention by an alien to become a citizen of the United States may be administered in the courts of record of the state. One who has so declared his intention to become a citizen may make a valid location of a mining claim.

At Law.

L. B. Wheat, for plaintiff.

W. P. Thompson and T. M. Patterson, for defendant.

HALLETT, J. This controversy arises out of conflicting locations of mining claims on the public mineral lands. At the trial plaintiff had a verdict, which defendant now moves to set aside, on various grounds. The errors alleged with reference to defendant's title will first be mentioned.

Defendant's title: May 12, 1881, D. E. Huyck and C. M. Collins located the Maximus lode, in Pollock mining district, Summit county, Colorado. July 8th, in the same year, they filed a certificate of location. The lode was discovered on the eastern or south-eastern slope of a very steep mountain, and about 160 feet below the crest of the mountain. The locators intended to lay the claim across the mountain, so that one-half or more should be on the north-western slope. At that point the mountain is almost impassable at any season of the year, and on the eighth of July, when the survey was made, it was thought to be wholly so. What was done towards setting stakes at the north-western end of the claim is described by the surveyor by whom the work was done, as follows:

“We then went back to the discovery cut and chained up the mountain some distance, when we came to a perpendicular precipice, or cliff of solid. 79 rock, over or around which we could not climb, owing to its precipitous nature and the fact that the crevices in the rock, and places where a foothold might have been had by one active enough to climb up the cliff, were filled with snow and ice, and it was both impracticable and dangerous to life and limb to get at the points where the stakes should be set. The side posts or stakes were set on the boundary lines of the survey somewhat short of or below the middle of the claim, and the end posts were placed further on, in conspicuous places, as near the side boundary lines as we could find places to put them. With my instrument I took the direction of the proper places of the upper end and side posts, and calculated the distances between the places where we did set them and their proper places, and marked its distance and direction from its proper place on each stake. The two middle side stakes and the two end stakes were set in such a way as to be evident and most likely to attract the attention of any one going up the gulch, and were within plain view of any one coming to the edge of the precipice above and looking down.”

At the time of this survey there was a practicable trail at no great distance south, and a wagon road some miles north, upon either of which it would have been possible to go to the other side of the mountain for the purpose of setting the north-western end stakes. And later in the season it was possible to pass over the mountain at the place where the Maximus claim was located, or very near that place. The same surveyor surveyed another location, called the Bernadotte, which covered a part of the Maximus territory, for the same parties, on the thirtieth day of August in the same year. With reference to the matter of getting over the mountain at that time, he testified as follows:

“This survey was made much later in the season than the other, and the difficulties of snow and ice which we had encountered in surveying the Maximus did not then exist, and we were able to climb up to the top of the ridge and set the end stakes in their proper places.”

Because of the difficulty or impossibility of getting over the mountain on the line of the Maximus claim on the eighth of July, when the survey was made, no stakes were set at the north-western end of the claim. In lieu thereof, witness stakes were placed on the southeastern slope of the mountain, as described by the surveyor in his testimony quoted above. The north-western end of the claim was not inaccessible from that side of the mountain. The stakes were properly set at that end of the claim in August, 1882, and it is not claimed that the point was then or at any time inaccessible, except as to the matter of getting over the mountain in a direct line from the discovery cut. Upon these facts a question was presented at the trial whether the Maximus claim was properly marked on the surface at the north-western end in July, 1881, or at any time before August, 1882, when a survey for patent was made, and stakes were properly set. Defendant relies on a statute of the state, (Rev. St. 630,) in these words:

“Where in marking the surface boundaries of a claim, any one or more of such posts shall fall by right upon precipitous ground, where the proper placing of it is impracticable, or dangerous to life or limb, it shall be legal and 80 valid to place any such post at the nearest practicable point, suitably marked to designate the proper place.”

But the act affords no support to the defendant's position. It relates to the matter of setting stakes where the point or place where they should be set is inaccessible, and not to such circumstances as were shown in the evidence. The locators of the Maximus claim could have reached the north-western end of the claim, at the date of the location, by routes which, although circuitous, were entirely practicable; and later in the season they could have passed over the mountain at the very place where the claim is located. To hold such marking of boundaries to be sufficient would be to disregard the act of congress (section 2324) and of the state (Rev. St. 630) which manifestly require something more. Upon full argument and mature consideration, the ruling at the trial that the Maximus claim cannot have effect on the north-western side of the mountain before the date of the patent survey in August, 1882, when the stakes were properly set, seems to be correct. Defendant also asserts title to some part of the ground in dispute under another location called the Bernadotte, made in the latter part of August, 1881. No question was made as to the manner of setting the stakes on this location, but there was a controversy as to the situation of the discovery cut with reference to the side lines of the claim, the existence of a lode therein, and perhaps some other matters. During the trial but little attention was bestowed on that location, but at the close counsel for defendant proposed to discuss its validity before the jury and to ask a verdict for some part of the ground in dispute on that title, and he now complains that he was not permitted to do so.

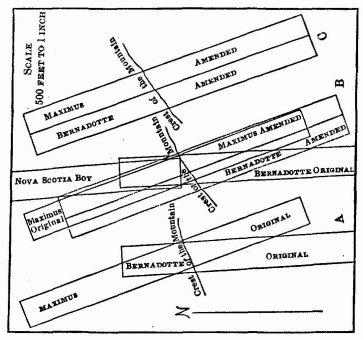

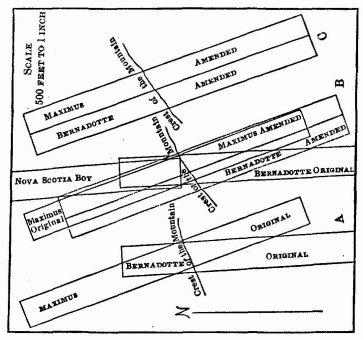

The ruling of the court in respect to that matter was founded on a change in the location at the time of the survey for a patent in August, 1882, which as to the ground in dispute, was supposed to defeat the earlier location in 1881. In the first location of the Maximus and Bernadotte, in the year 1881, they were relatively to each other and the crest of the mountain in the position shown in diagram, A.

In the survey for patent in August, 1882, the Maximus was carried something like 190 feet in a south-easterly direction, so as to give it greater length on the south-eastern slope of the mountain, and less on the north-western slope; and the general direction of the claim was changed so as to carry it over on plaintiff's claim a distance of 30 feet more than was previously covered by it. The Bernadotte claim was changed to the north-easterly side of the Maximus and parallel with the latter, so as to make them uniform in length and direction. The relative position of these claims thus changed is shown in diagram, C. And the position of the claims as originally located and in the survey for patent, together with plaintiff's claim, the Nova Scotia Boy, is shown in diagram, B.

The most that can be demanded on behalf of the Bernadotte claim 81 is, that the territory embraced in the original and amended locations of that claim, and which is also within the lines of plaintiff's location, shall be regarded as subject to and held by defendant under the first location certificate. Where rights have accrued to others in respect to some part of the territory covered by the location, and the change of lines is radical and complete, as in this instance, that proposition may be open to discussion. But conceding it to be indisputable, there was no evidence that any part of the ground in dispute was in that situation. It is true that in some of the plats used by the witnesses, a small triangular piece of ground appeared to be covered by the original and amended locations of the Bernadotte, and in  plaintiff's location called the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2. It is so represented in the diagram last above mentioned. But no description of the place was given, and the jury would not have been able to define the tract if required to do so. A party must always show the nature and extent of his demand, and where, as in this case, it is real estate and a part of a larger tract claimed, he must show what part. Failing in that respect, defendant was not entitled to go to the jury on the first location of the Bernadotte, nor on the first location of the Maximus, for want of boundary stakes, as already explained. The jury was correctly instructed that the Maximus and Bernadotte locations could have no earlier date than that of the survey for patent in August, 1882, and the question to be determined was whether the plantiff's 82 title to the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2, had then accrued by the previous performance of all acts necessary to a valid location.

plaintiff's location called the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2. It is so represented in the diagram last above mentioned. But no description of the place was given, and the jury would not have been able to define the tract if required to do so. A party must always show the nature and extent of his demand, and where, as in this case, it is real estate and a part of a larger tract claimed, he must show what part. Failing in that respect, defendant was not entitled to go to the jury on the first location of the Bernadotte, nor on the first location of the Maximus, for want of boundary stakes, as already explained. The jury was correctly instructed that the Maximus and Bernadotte locations could have no earlier date than that of the survey for patent in August, 1882, and the question to be determined was whether the plantiff's 82 title to the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2, had then accrued by the previous performance of all acts necessary to a valid location.

Plaintiff's title: The first work on the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2, was done in 1879 by Benjamin T. Vaughn, the locator of the claim, who was an alien. A. discovery shaft or cut, as required by the statute, was not made in that year, however, and it became a question throughout the trial whether such work was done at any time before suit. Plaintiff offered evidence tending to prove that the work was completed in 1880, and annual work was done on the claim in the years 1881 and 1882. This was denied by witnesses for defendant, and the matter was contested before the jury in the usual way. As already stated, Vaughn, who located the claim, was an alien, and it was shown that he declared his intention to become a citizen in a district court of the state, May 30, 1881. Defendant objected that he was not qualified to make a location in the year 1880, when the claim was said to have been located; nor was he so qualified at any time before the discovery of the Maximus lode by defendant's grantors on the twelfth day of May, 1881. As to the declaration of Vaughn of his intention to become a citizen, a court of the state was not competent to receive it. Defendant maintained that authority to naturalize an alien could not be exercised by any state tribunal, and it resides only in the federal courts. To this plaintiff replied, that any one, citizen or alien, may make a location, and the competency of the latter cannot be questioned except by the government. A location by an alien who has not declared his intention to become a citizen shall be maintained until the government avoids it. These propositions, renewed with some energy on the motion for new trial, do not demand much consideration. If Vaughn was not qualified to make a location before May 30, 1881, his declaration of that date made him so. And as defendant's right, whatever it may be, to the ground in controversy accrued long after that time, Vaughn's prior incompetency cannot avail. The only doubt touching that matter is whether, on declaring his intention to become a citizen, Vaughn could have advantage of what he had previously done towards locating the claim, and as to that, assuming that no other claim to the ground had intervened, no reason is perceived for denying his right to the fruits of his labor. Indeed, it may be contended that he should hold, from the first act done, Mb qualification to locate a claim, beginning with his declared purpose to enjoy the bounty of the government. But we are not concerned with that inquiry in this case. It is enough to say that Vaughn became qualified under the act of congress, in May 1881, and that what he had then done towards locating the claim should accrue to him as of that date.

The authority of courts of record in the several states, under the act of congress, (Rev. St. 2165,) to confer the right of citizenship, has been accepted in practice and recognized without discussion by courts since the act was passed. Campbell v. Gordon, 6 Cranch, 176; Stark v. Chesapeake Ins. Co. 7 Cranch, 420;

83

Lanz v. Randall, 4 Dill. 425. A discussion of the question in a court of original jurisdiction at this time would seem to be unnecessary. If defendant wishes to deny the power of congress to confer such jurisdiction on courts of states, the supreme court is a more appropriate forum for the discussion. The position of the plaintiff, that an alien who has not declared his intention to become a citizen may make a valid location of a mining claim, finds no support in the statute. Rev. St. 2319. But this also was an immaterial question at the trial, since Vaughn was held to be qualified after his declaration of intention to become a citizen in May, 1881, and the jury supported his title as having become full and complete prior to August, 1882.

The motion will be overruled.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Jeffrey S. Glassman.

plaintiff's location called the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2. It is so represented in the diagram last above mentioned. But no description of the place was given, and the jury would not have been able to define the tract if required to do so. A party must always show the nature and extent of his demand, and where, as in this case, it is real estate and a part of a larger tract claimed, he must show what part. Failing in that respect, defendant was not entitled to go to the jury on the first location of the Bernadotte, nor on the first location of the Maximus, for want of boundary stakes, as already explained. The jury was correctly instructed that the Maximus and Bernadotte locations could have no earlier date than that of the survey for patent in August, 1882, and the question to be determined was whether the plantiff's 82 title to the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2, had then accrued by the previous performance of all acts necessary to a valid location.

plaintiff's location called the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2. It is so represented in the diagram last above mentioned. But no description of the place was given, and the jury would not have been able to define the tract if required to do so. A party must always show the nature and extent of his demand, and where, as in this case, it is real estate and a part of a larger tract claimed, he must show what part. Failing in that respect, defendant was not entitled to go to the jury on the first location of the Bernadotte, nor on the first location of the Maximus, for want of boundary stakes, as already explained. The jury was correctly instructed that the Maximus and Bernadotte locations could have no earlier date than that of the survey for patent in August, 1882, and the question to be determined was whether the plantiff's 82 title to the Nova Scotia Boy, No. 2, had then accrued by the previous performance of all acts necessary to a valid location.