In re ALDRICH and others.

District Court, N. D. New York.

March, 1883.

v.16, no.3-24

1. TAXATION OF NEGOTIABLE PAPER—NOTES PAYABLE IN GOODS.

Section 19 of the act of February 8, 1875, which provides “that every person, firm, association, other than national-bank associations, and every corporation, state bank, or state banking association, shall pay a tax of 10 per centum on the amount of their own notes used for circulation and paid out by them,” must be construed as limited in its effect to notes payable in money; otherwise all sorts of negotiable paper, such as “grain receipts,” fare tickets, and the like, might be subject to the same taxation

3702. SAME—NOTES CONTEMPLATED BY THE NATIONAL-BANK ACT.

Section 5172 of the Revised Statutes provides how the notes contemplated by the national-bank act shall be printed and what they shall contain. No provision is made for a note for less than one dollar. A note for a fractional sum is not only unknown to the law, but its issue is unlawful. Section 3583. The supreme court, by deciding that an obligation “payable in goods” was not illegal, has left the inference to follow almost necessarily that it was not such a note as was contemplated by the statute, and therefore not taxable.

At Law.

Martin I. Townsend, Dist. Atty., for the United States.

John L. White, for the receiver.

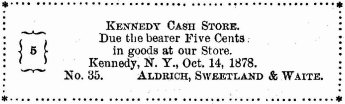

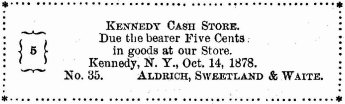

COXE, J. In the years 1878, 1879, and 1880, George A. Aldrich, L. Orlando Sweetland, and Charles M. Waite were engaged in mercantile pursuits at Kennedy, New York. Prior to February, 1880, they issued promises or certificates, of various denominations, in the words and figures as follows:

The others issued were, mutatis mutandis, in the same form, the amounts ranging as high as five dollars. About $5,000 of this paper was circulated, to a limited extent, in the immediate locality. In February, 1880, the firm failed, and a receiver was appointed, who, having reduced the property to money, now holds it ready for distribution. The collector of internal revenue for the thirtieth collection, district having assessed $498.88, or 10 per cent., on this circulation, demanded that sum of the receiver.

The questions involved are: First, whether the said obligations are taxable under the act of February 8, 1875; and, second, whether the United States should be paid in full, or pro rata with the other creditors.

Section 19 of the said act provides—

“That every person, firm, association, other than national-bank associations, and every corporation, state bank, or state banking association, shall pay a tax of 10 per centum on the amount of their own notes used for circulation and paid out by them.”

In U. S. v. Van Auken, 96 U. S. 366, the supreme court held that fin obligation in almost precisely similar words was not, within section

3713583 of the Revised Statutes, “intended to circulate as money.” The court says:

“Here the note is for ‘goods’ to be paid at the store of the furnace company It is not payable in money, but in goods, and in goods only. No money could be demanded upon it. It is not solvable in that medium. Watson v. MoNairy, 1 Bibb, 356. The sum of ‘fifty’ cents is named, but merely as the limit of the value in goods demandable and to be paid upon the presentation of the note. Its mention was for no other purpose, and has no other effect. In the view of the law, the note is as if it called for so many pounds, yards, or quarts of a specific article.”

Is such a paper taxable, as a note used for circulation? It is thought that it is not. If these papers, which are simply evidences of credit, and nothing more, are liable to taxation, it is difficult to perceive why any paper representing value and passing from hand to hand is not equally liable. Where is the collector to draw the line, if not at notes payable in money? If allowed to go beyond, how can he stop until every species of negotiable paper has been taxed? Why are not grain receipts, which circulate so freely on the Chicago market, bills of lading, and invoices, subject to the tax?

The construction of the statute contended for by the collector could be still further strained to include railroad, street-car, and ferry tickets; indeed, every peddler of milk on a country route might be required to pay on the milk tickets “circulated” by him. Where is the distinction in principle between these cases and the case at bar?

Mr. Parsons says, in his work on Contracts, (vol. 1, p. 247:) “As the negotiable bill or note is intended to represent and take the place of money, it must be payable in money, and not in goods.” See also Austin v. Burns, 16 Barb. 643; Jerome v. Whitney, 7 Johns. 321; Thomas v. Roosa, Id. 461; Edwards, Bills & Notes, (3d Ed.) §§ 147, 148.

The obligations here are simply, due-bills or certificates, giving the holder the right to exchange them for butter, eggs, tea, or coffee, at a certain place. If, instead of the language employed, they had recited that there was “due the bearer one pound of tea (50 cents per pound) at our store,” etc., would the change be other than a verbal one? Does the fact that the holder has an option limited only by the capacity of the stock in trade change the nature of the paper? It cannot be successfully maintained that the statute was intended to cover such obligations. Section 51,72 of the Revised, Statutes provides how the notes contemplated by the national-bank act shall be printed, and what they shall contain. No 372 provision is made for a note for less than one dollar. A note for a fractional sum is not only unknown to the law, but its issue is unlawful. Section 3583, supra. The supreme court, by deciding that an obligation payable “in goods” was not illegal, has left the inference to follow almost necessarily that it was not such a note as was contemplated by the statute, and therefore not taxable.

The whole tenor of the act, and the sections relating to taxation, indicates that it was the intention of congress to tax only such obligations as circulated as money. Whenever a tax is laid on negotiable paper other than bank notes, its character is particularly specified, and it is always money or its equivalent; as, for instance, in section 3408, where a tax is imposed on the average amount of circulation, “including, as circulation, all certified checks, and all notes and other obligations calculated or intended to circulate or to be used as money.” In Nat. Bank v. U. S. 101 U. S. 1, the chief justice, having under consideration section 3413, says:

“The tax thus laid is not on the obligation, but on its use in a particular way. As against the United States, a state municipality has no right to put its notes in circulation as money. * * * The tax is on the notes paid out, that is, made use of as a circulating medium.”

It is not contended that there was, prior to February 8, 1875, any law applicable to this case. 18 St. at Large, p. 311, §§ 19-21. A careful reading of these sections, however, would seem to justify the conclusion that they were intended to extend the law so as to apply to those, other than national-bank associations, engaged in banking business, whether corporations or individuals* to make the law applicable to new persons, but not to new subject-matter.

The tax, under the act of 1875, is paid in precisely the same manner as the tax on bank deposits, oapital, and circulation; the meaning of the word “notes” is not enlarged or explained, and no language is used to indicate that it was the intention of congress to give to it any different signification than that given in the original act.

The conclusion reached is that the statute does not cover obligations which simply entitle the: holder to a certain amount of merchandise—limited by the sum stated—at the store of the party who issues them. The system may be a pernicious one; very likely a tax should be imposed; but if the foregoing views are correct it cannot be done under existing laws.

The opinion of Attorney General Devens (25 Int. Rev. Rec. 167) is cited as holding a different doctrine. Although the collector was advised to proceed and levy the tax, the attorney general expressed 373 grave doubts regarding the legality of such action, and was apparently influenced in arriving at this conclusion by a desire to obtain a judicial construction of the statute, “since thus only can the question be brought to an authoritive determination of the highest federal tribunal.” He doubted whether obligations payable in goods came within the letter of the statute, but thought that they did come “within the mischief intended to be remedied by the statute.” Although the opinion is entitled to great weight, it cannot be regarded as controlling, especially where it is conceded that the question is a doubtful one.

As the conclusion reached disposes of the case, it will not be necessary to consider the second question stated above.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Cicely Wilson.