ELGIN MINING & SMELTING Co. and others v. IRON SILVER MINING Co.*

Circuit Court, D. Colorado.

November, 1882.

1. MINING CLAIMS—END LINES.

In the location of mining claims, “end lines” must be established as required by the statute, and where the locator fails to do this, the courts will not fix them by implication. If the end lines be absent, or so placed as not to define the right of the locator to the exterior parts of the lode, the defect cannot be supplied.

2. SAME—VALID ONLY WITHIN SURFACE LINES.

In such case the location may-be valid for all that can be found within the surface lines, but beyond those lines an essential element of the right to follow the lode is wanting, and therefore the right cannot exist.

Markham, Patterson & Thomas and M. B. Carpenter, for plaintiffs.

Jonas Seeley, for defendant.

HALLETT, D. J. On the twenty-ninth of June last, the Elgin Mining & Smelting Company, a corporation of the state of Illinois, and several natural persons, exhibited in this court their bill of complaint against the Iron Silver Mining Company, a corporation of New York, to restrain a trespass of the latter company on the Gilt-Edge mining claim, located in Lake county, Colorado. Asserting title to the Gilt-Edge claim, plaintiffs alleged that they had found a lode therein containing rich and valuable ore, and the defendant, claiming the same ore as being in and of a certain other lode owned by it and called the Stone lode, was proceeding to remove the ore and convert it to its own use.

After notice, defendant appeared and filed affidavits in opposition to plaintiff's application for injunction. As disclosed in the bill and affidavits, the controversy was mainly as to the right of defendant to follow the lode from the Stone claim, owned and worked by it, beyond the lines of that claim and into the adjoining claim owned by plaintiffs.

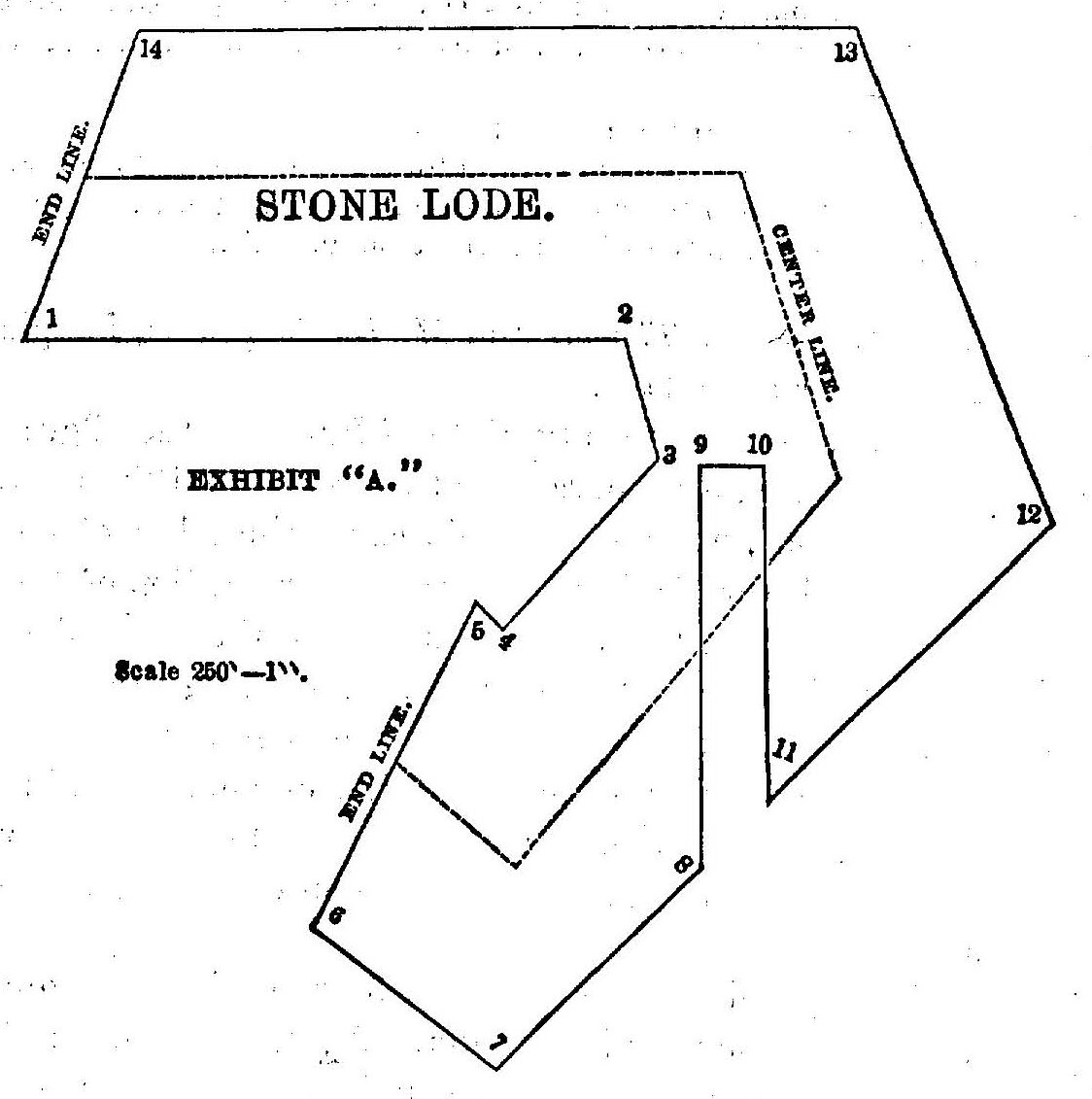

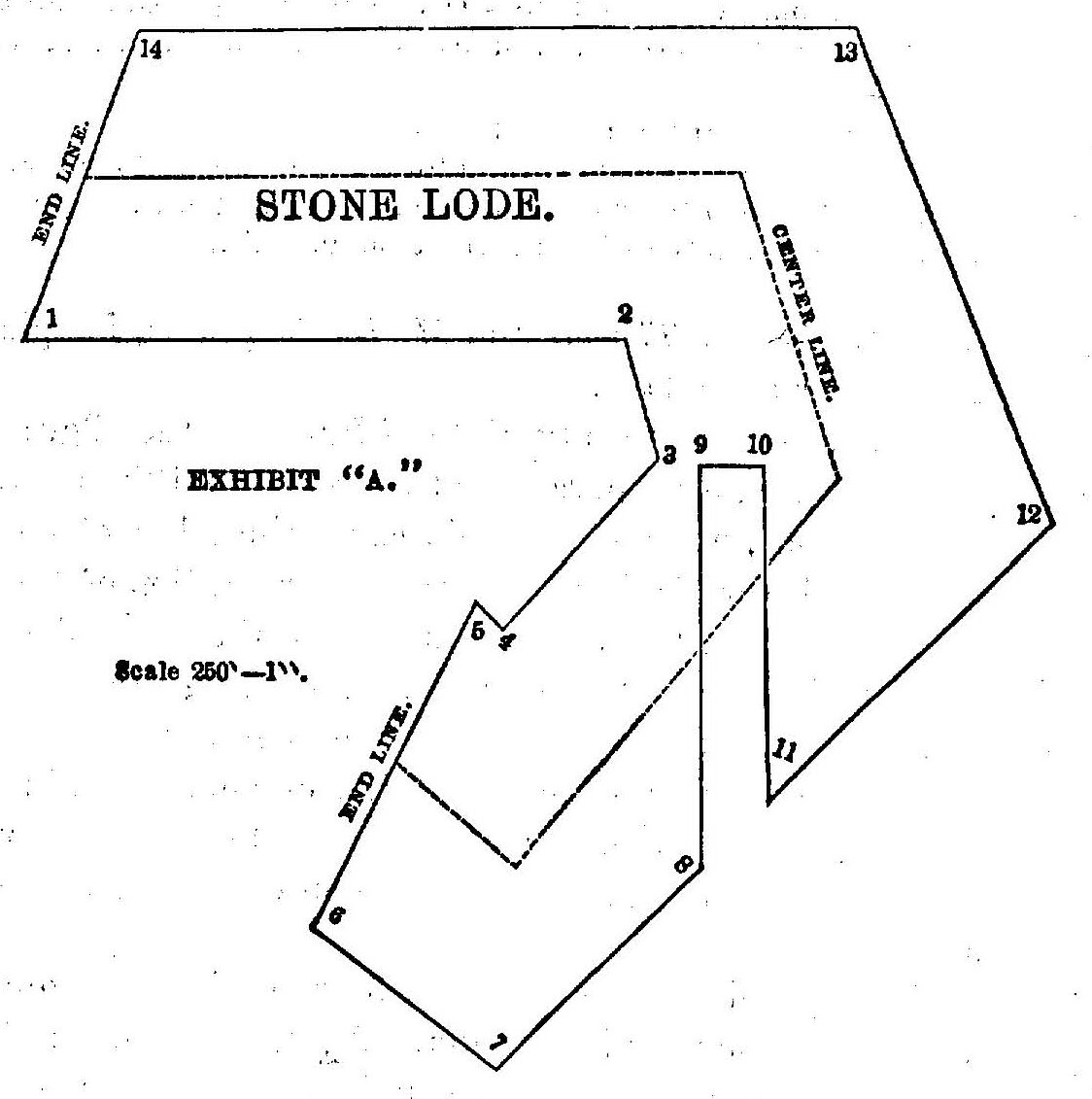

378In its ordinary form, this controversy presents questions of fact as to the existence of the lode in both claims, or the extension of it from one claim to the other. One party, claiming to own the top and apex of the lode, seeks to follow; it on its dip through the side lines of his claim into the land adjoining, as the right so to follow it is defined in section 2322, Rev. St. the other, unable to deny the force of the statute, appeals to a jury on the point whether the top and apex of the lode arises in the ground of his opponent, or, if there, whether the lode descends from that region to the place in dispute. In addition to these questions, which were not pressed at the hearing, there is another and a very extraordinary question arising out of the peculiar form and relative position of the claims. And as it is very difficult to describe the claims fully in words, so as to explain the matter in dispute, a diagram will serve the purpose better:

The ore for which the parties are contending is within the surface lines of plaintiff's claim, (the Gilt Edge,) eastward from defendant's claim, (the Stone,) and adjoining the latter. It is reached by means of a perpendicular shaft from plaintiff's claim; and a tunnel or level, 379 following, it is said, the Course of the vein from a point in defendant's claim down the hill-side, and below the other. Assuming, for the present, that the top and apex of the lode has been found in the Stone claim, owned by defendant, and that the lode in a downward course, and with distinct boundaries, passes eastward out of that claim and into the Gilt-Edge claim, owned by the plaintiff, to the place in dispute, the right of defendant to follow it without the lines of the Stone claim, and take the ore therein, is denied on the ground that the latter claim is without end lines to define and limit Such right. In the act of congress relating to mineral lands it is provided, in section 2320, that “the end lines of each claim shall be parallel to each other;” and in section 2322, that the right of possession to the “outside part” of veins or ledges, referring to such parts as extend beyond the Bide lines of the location, “shall be confined to such portions thereof as lie between vertical planes drawn downward as above described through the end lines of their locations, so continued in their own direction that such planes will intersect such exterior parts of such veins or ledges.”

In the Flagstaff Case, 98 U. S. 467, the acts relating to mineral lands were said to require that locations of veins or lodes shall be made lengthwise in the general direction of such veins or lodes on the surface of the earth; and that the end lines are to cross the lode and extend perpendicularly downwards, and to be continued in their Own direction either way horizontally.

The general practice in mining districts of making locations in the form of a parallelogram conforms to this view, which is now universally accepted as correct. Obviously it was not intended that a locator should secure more of the lode in the “outside parts” extending beyond the side lines than he could obtain on the course of the lode within the limits of the location. In other words, by a proper location he could secure 1,500 feet on the strike of the lode, and by the extension of the planes of the end lines he would be limited to the same number of feet laterally in pursuing the lode downwards without the side lines. Such limitation is necessary to define the miner's right beyond his own territory. If, when once without his own lines, he could turn to the right or left in search of ore, the limitation to 1,500 feet of the length of the vein would be made wholly nugatory, and there would be no end of conflicts between adjacent owners, for which no just rule of settlement would be found.

Referring to the defendant's Stone claim, the line at the northwesterly end is said to be one of the end lines, and it is so marked 380 on the diagram. In the first course of the location from that line, which is S. 83 deg. E., there is no corresponding end line; and the same is true of the second course, S. 18 deg. E.; and the third course, S. 45 deg. W., very nearly. It will be observed that the location is in the form of the letter A, truncate, and the locator has made a part of the inner line of the southern leg of the location 300 feet in length, to correspond in direction with the line at the north-westerly end, and called it an end line. With superficial attention to the letter of the law, and in utter ignorance and disregard of its principles, the two lines were made of equal length and parallel to each other, but so arranged that they can never perform the office assigned to them in the law. What is called the southern end line is really on the north-west side of the greater part of the claim, and so placed that, when extended in a northerly direction, it must enter the inner line of the claim in a short distance from corner No. 5. In this position that line cannot enter the field north and east from the claim, being intercepted by the claim itself. And so it appears that, eastward and southward from the north-western end of the claim, there is no line which can be recognized as an end line, and the claim has but one end line, or perhaps none whatever.

This view was not controverted at the hearing, but it was said that end lines may be a matter of legal inference and deductions from established facts to control even the act of the locator of the claim. As the law requires that a location shall be made along the course or strike of a vein at the surface of the earth, the end lines must of necessity be at right angles to the course. And whenever the course or strike can be ascertained, at the points where it passes from the location, end lines should be fixed at right angles thereto, without reference to the end lines laid in the location. To apply this rule to defendant's claim, lines should be drawn parallel to each other at each end, and where the outcrop of the vein is said to pass out of the location, and in the general direction east and west, the strike of the vein being north and south.

The circular form of outcrop is thought to be the result of erosion in California gulch, which comes down through the middle of the claim, and at some remote time the outcrop may have extended directly across the gulch between the ends of the claim, so as to admit of a location in the usual form with end lines, as now proposed to be laid, in the general direction east and west. It is contended that in the location of a claim, which must of necessity be made before the strike of the lode can be ascertained, it is too much to expect 381 the locator to lay his end lines in the proper direction, and locations made at various angles of divergence from the strike of the lode are cited to illustrate the fact that by a slight deviation from the proper course the object of making a location may be defeated. This, however, is only to say that it is difficult to make a good location of a mining claim when the situation of the ore is unknown, and that if the locator fails to lay his claim so as to secure the ore, the law should correct his mistake. Plainly enough, the law requires the locator to fix the boundaries of the claim, offering the bounty of the government to the extent of the public domain from which to make the best possible selection. If the locator fails to choose wisely and well, the failure is with him, and it cannot be imputed to the law. There is no greater reason for saying that the end lines shall be established by inference and presumption from the course of the lode, than that the side lines shall be so established. The rule of the early miner's law, which obtained in some mining districts before the statute was enacted, was of the character which we are now asked to adopt. By locating on the vein the miner secured the number of feet allowed him, wherever it might extend, with surface ground adjacent, and, of course, the boundaries of the claim could only be known from the course of the lode. By the act of congress that rule was changed, and it was required that the boundaries of the claim shall be marked on the ground, and end lines and side lines are referred to in a way to show that they must be laid down with care. Under such a statute it cannot be necessary to discuss at length the power of the court to establish lines by construction, for no such power can exist. The end lines established by the locator must control, and if absent, or if so placed as not to define the right of the locator to the exterior parts of the lode, the defect cannot be supplied.

In that case the location may be valid for all that can be found within the surface lines, but beyond those lines an essential element of the right to follow the lode is wanting, and therefore the right cannot exist. With some information as to the situation of the ore, and the law relating to the subject, the end lines of the Stone claim could have been laid as it is now said they should be placed, and the failure to do so was owing to ignorance of facts necessary to intelligent action. It presents the common case of failure to obtain property through a mistake of fact or law, for which the party seeking the property is alone responsible. Against such error and misfortune the law does not relieve.

382At the hearing, on plaintiff's motion for injunction to restrain the iron company from working within the limits of the Gilt-Edge claim, these reasons were thought to be sufficient to support the application, and the injunction was allowed. Recently the defendant has brought in a cross-bill, asking to enjoin the plaintiff from working in the same ground, and on that motion the whole subject has been reviewed, with the result now to be stated.

The defendant, in virtue of its ownership of the Stone claim, has no right to anything beyond the lines of that claim in any direction, and therefore the motion must be denied.

* From the Colorado Law Reporter.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Mark A. Siesel.