SHAW STOCKING Co. v. MACK and another.

Circuit Court, N. D. New York.

June, 1882.

1. TRADE—MARK DEFINED—OBJECT AND PURPOSES OF.

A trade-mark is a mark by which the wares of the owner are known in trade; its object being—First, to protect the party using it from competition with inferior manufactures; and, second, to protect the public from imposition.

2. SAME—OF WHAT MAY CONSIST.

The trade-mark may consist of a token, letter, sign, or seal. Names, ciphers, monograms, pictures, and figures may be used, and numerals united.

3. SAME—NUMERALS—INFRINGEMENT.

Where numerals constituted one of the most prominent features in plaintiff's design, and the same numerals were used in a similar design by defendants, such use, when adopted to designate the same kind of articles, is calculated to aid in deceiving the public, and is an infringement of plaintiff's trade-mark.

4. SAME—SIMILITUDE.

It is enough that such similitude exists as would lead an ordinary purchaser to suppose that he was buying the genuine article and not the imitation; and it is not necessary that the resemblance should be such as would mislead an expert, or such as would not be easily detected if the original and spurious were seen together.

5. SAME—RIGHT TO USE OF TRADE-MARK.

The right to a trade-mark is a right depending on use; and where complainant had used certain numerals long enough to convey to any one versed in the nomenclature of the trade a precise understanding of what goods were intended, when such numerals were used alone, disconnected from any extrinsic information, its right to their exclusive use as a trade-mark must be upheld.

6. SAME—PROTECTION BY INJUNCTION.

An injunction will be granted to restrain the defendants from using the numerals appropriated by plaintiff, to designate the same kind of goods sold by the defendants and not made by the plaintiff, and from using on their labels a word printed in script, with a flourish underneath, in imitation of a word used by the plaintiff on its labels.

Miller & Fincke, for complainant. John L. S. Roberts, of counsel.

Thomas Wilkinson, for defendants. E. Countryman, of counsel.

COXE, D. J. The Shaw Stocking Company is alleged to be a corporation engaged in the manufacture and sale of hosiery at Lowell, Massachusetts. Its goods differ in some important respects from the productions of other manufacturers, and have by virtue of their inherent worth acquired a wide-spread reputation and popularity. The complainant, with perhaps a pardonable assurance, insists that these goods possess many excellent and novel qualities and characteristics hitherto unknown or unapplied. It is not disputed, however, that in some respects the assertion is well founded. The defendants apparently 708 entertained a very high opinion of the complainant's hosiery, for as late as April 19, 1882, they wrote as follows: “Now, since you have determined you will not give us further supplies, * * * we do not care to continue our hosiery trade at all. * * * We want the best make or none,” etc.

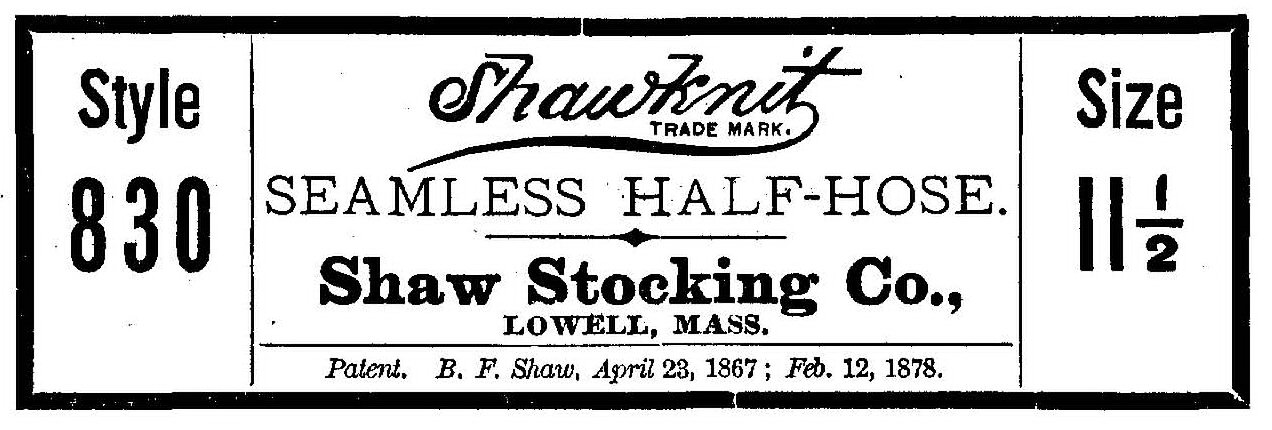

Upon the question of quality it is sufficient to say that no one of the affiants produced by the defendants alleges that there are goods in the market superior to the complainant's. Some are said to be equal, none superior. For a period of two years complainant's hosiery has been packed and sold in boxes, to which were attached labels in the following form:

The central compartment of the label was the same in every instance, without reference to the contents of the boxes. The figures at either end differed according to the style and size of the hosiery, the numerals “830” having long been used by complainant to designate seamless half-hose of a mottled drab color manufactured by it. Half-hose of this particular variety had been advertised by these numerals, were known to the trade as “830's,” and as such had become popular as the wares of complainant.

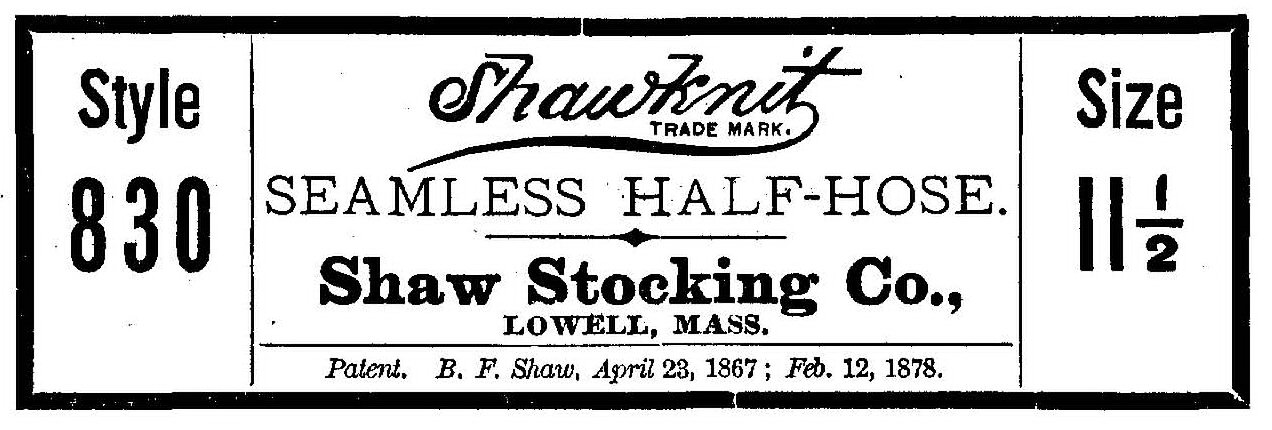

In May, 1881, complainant commenced selling to the defendants' firm at Albany large quantities of its goods. At the request and solicitation of defendants, complainant sent them several thousand circulars or price-lists, signed by the Shaw Stocking Company, and containing the announcement that the wares manufactured by that company and described in the circular could be obtained of “Mack & Co.,” who would supply them to buyers at the prices indicated. These circulars were sent by the defendants extensively to their customers throughout the state, it being generally understood that the “Shawknit” goods could be obtained as favorably at Albany as at Lowell. The statements contained in the circular, emanating as it did directly from the company, taken in connection with the fact 709 that the defendants advertised themselves on their bill-heads as “manufacturers and manufacturers' agents,” caused it to be commonly supposed that Mack & Co. were the New York agents of the complainant, or at least conveyed information from which such an inference could reasonably and properly be drawn by the commercial world. In March, 1882, the defendants having maintained this connection with the complainant for nearly a year, and having a large quantity of its hosiery undisposed of, commenced putting up and selling, without previous notice, other goods, similar in color and texture, but inferior in many respects to its productions, as complainant insists, and lighter in weight and cheaper in price, as defendants admit. These goods were sold under labels like the following:

The wares so labelled and sold were not manufactured by the defendants, but were purchased of stocking makes at Birmingham, Connecticut, the labels on the boxes being removed by the defendants and the above labels substituted, not only on the Birmingham, but also on the “Shawknit” boxes.

Defendants' own account of their action in this regard, and of the motives which prompted it, is stated under date of April 11, 1882, in the following words:

“This state of affairs [viz., the alleged withdrawal of styles by the complainant] was the first incentive to using Birmingham hose, and our idea was to work the two makes together in such a way as to save us from loss on yours, which were the higher cost, and at the same time in such a manner that any variations from your regular prices would not reflect on you, or become detrimental to your interests in any manner, and, at the same time, enable us, on an average cost, to make something; and consequently we had our labels printed and our own bands, putting them on all,—your make and Birmingham both,—making no claim as to any particular or distinctive manufacture, only retaining in the label the number adopted by you to distinguish style,” etc.

710This letter was written after notice of complainant's grievance, and it is fair to assume that it contained as favorable a presentation of defendants' case, and their motives and intentions, as at that time suggested itself to the mind of the letter-writer.

The foregoing facts are in their essential features undisputed.

The complainant also produced affidavits tending to show that many dealers had been deceived by the defendants' labels; that “Shawknit” goods had been ordered and paid for as such, and the Birmingham goods supplied by defendants in response to such orders; that defendants' agents sold by “Shawknit” samples, but the orders were not filled with “Shawknit” goods.

The defendants deny that they have been guilty of any attempt to deceive the public, and offer an explanation of the various occurrences relied on by the complainant to establish a fraudulent intent. They also produce a number of affidavits intended to establish two or three leading propositions, viz: That the Birmingham is not inferior to the “Shawknit” hosiery; that the numerals used by complainant are intended simply and solely to designate the quality and style of its goods, and not for the purpose of indicating their origin or identifying their makers; that the two labels are so dissimilar that no one, exercising ordinary care, would be misled.

Defendants also produce an affidavit made by one of their agents, in which the affiant states that on the first day of June, 1882, he visited the city of New York, and in five stores there, found seamless half-hose made by different manufacturers, the quality being distinguished by the numerals “830.” He fails, however, to give the name of any of the manufacturers, the date when the figures were first used, or any data upon which the complainant could base an investigation.

The question to which the attention of counsel was chiefly devoted on the argument was whether the complainant had an exclusive right to the number “830” to designate and distinguish its hose of a particular variety.

Broadly defined, a trade-mark is a mark by which the wares of the owner are known in trade. Its object is twofold: First, to protect the party using it from competition with inferior articles; and, second, to protect the public from imposition. There is hardly a limit to the devices that may be thus employed; the whole material universe is open to the enterprising merchant or manufacturer. Any thing which can serve to distinguish one man's productions from 711 those of another may be used. The trade-mark brands the goods as genuine, just as the signature to a letter stamps it as authentic. The trade-mark may consist of a token, letter, sign, or seal. Names, ciphers, monograms, pictures, and figures may be used. Why not numerals united? What consistency is there in allowing it in a combination of letters, but denying it in a combination of figures?

A careful examination of the authorities cited by the learned counsel for the defendants leads to the conclusion that where the courts have refused protection to alleged trade-marks composed of letters or numerals, it has been because on the facts of each case, it was determined that the figures or letters were intended solely to indicate quality, etc., and not because figures and letters in arbitrary combination are incapable of being used as trade-marks. It is very clear that no manufacturer would have the right exclusively to appropriate the figures 1, 2, 3, and 4, or the letters A, B, C, and D, to distinguish the first, second, third and fourth quality of his goods, respectively. Why? Because the general signification and common use of these letters and figures are such, that no man is permitted to assign a personal and private meaning to that which has by long usage and universal acceptation acquired a public and generic meaning. It is equally clear, however, that if for a long period of time he had used the same figures in combination, as “3214,” to distinguish his own goods from those of others, so that the public had come to know them by these numerals, he would be protected. The courts of last resort in Connecticut, in Massachusetts, and in New York have distinctly held that doctrine. Boardman v. Meriden, 35 Conn. 402; Lawrence Co. v. Lowell Mills, 129 Mass. 325; and Gillott v. Esterbrook, 48 N. Y. 374,—the numerals sustained being respectively “2340,” “523,” and “303.” The defendants concede this, but insist that the case of Manufacturing Co. v. Trainer, 101 U. S. 51, affirms a contrary doctrine, and that it should be controlling. Undoubtedly the decisions of the supreme court should be followed, but I do not understand the doctrine enunciated by the court in this case as conflicting with the general principle contended for by the complainant. The case appears to have been decided upon the theory that the letters “A, C, A” were simply used to denote quality and not origin, and turned mainly upon the question of fact as to whether or not they were so used. Upon this question the court was divided. Mr. Justice Field, who delivered the prevailing opinion says, at page 54: “The object of the trade-mark is to indicate, 712 either by its own meaning or by association, the origin or ownership of the article to which it is applied.” And at page 55: “It is clear from the history of the adoption of the letters ‘A, C, A,’ as narrated by the complainant, and the device within which they are used, that they were only designed to represent the highest quality of ticking which is manufactured by the complainant, and not its origin;”—hence Mr. Justice Field's decision. Mr. Justice Clifford, in an able opinion, dissented, and directly antagonizing the foregoing interpretation of the evidence, says, at page 59: “Attempt is made in argument to show that the symbol of the complainants was not adopted by them for any other purpose than to designate the grade or quality of the fabric which they manufacture and sell in the market; but it is a sufficient answer to that proposition to say that it is wholly unsupported by evidence, and is decisively overthrown by the proof introduced by the complainants;”—hence Mr. Justice Clifford's dissent. Had the evidence been understood by the two justices alike, there is no reason to believe that there would have been any disagreement as to the law.

Subsequent to the decision of the supreme court in the Trainer Case, and with full knowledge thereof, the case of the Lawrence Co. v. Lowell Mills, supra, was decided by the supreme court of Massachusetts. There is a striking resemblance between that case and the case at bar. Rarely is there such a similarity between the facts of two cases wholly separate and distinct. The trade-mark in the Massachusetts case consisted of an eagle surmounting a wreath formed of the branches of the cotton plant. Inside the wreath, and printed in a circle, were the words “Lawrence Manufacturing Company;” underneath it the word “trade-mark;” and below all the figures “523.” As in the case at bar, the word “trade-mark” does not appear to have had any connection with the numerals. It was attached to and connected with the vignette. The figures were below and separated from it. This device had been used to designate hosiery of a certain grade for many years, and was known and recognized as indicating that the goods so marked were of the plaintiff's manufacture. Other numerals, and in fact another device, had, prior thereto, been used to indicate the same grade of hosiery. The wreath and eagle, without the figures “523,” or any figures, had also been used on other grades of goods. Defendants' device was an eagle surmounting a double circle or garter, on which were the printed words “extra-finish iron frame,” and beneath were the figures 713 “523” in the same relative position. The eagle and garter were used by defendant before the eagle and wreath were used by plaintiff, and plaintiff made no claim to them disconnected from the figures. The court, after referring to and considering the Trainer Case, and other cases, proceeds to say:

“These considerations would be decisive, if the plaintiff here claimed the exclusive right to the numerals ‘523,’ when used only to indicate the quality and not with reference to the origin, of the goods. But such is not the plaintiff's position. Its claim is that the purpose of using these figures in connection with the other parts of its trade-mark was to aid the buyer in distinguishing its goods from similar goods made and sold by others.”

This is precisely the position of the complainant here, and could hardly have been stated more tersely. In that case the goods were known and described as “523's;” in this as “830's.” Again, the court says

“The defendant's limitation was produced by using the same figures, printed in the same style, and placed as to the other parts of the device in the same relative position as the plaintiff's. These numerals constituted one of the most prominent features in the plaintiff's design, and, when used in connection with the rest of the defendant's mark were calculated to aid in deceiving the public. It is not necessary that the resemblance produced should be such as would mislead an expert, nor such as would not be easily detected if the original and the spurious were seen together. It is enough that such similitude exists as would lead an ordinary purchaser to suppose that he was buying the genuine article and not an imitation.”

I understand this case as holding distinctly that a party who has adopted an arbitrary combination of figures to designate his wares, and to distinguish them from the productions of others, is entitled to protection in the use of those figures. I am unable to see any difference in principle between it and the case at bar, and, as the latest adjudication directly upon this subject, I think it should be controlling.

That the facts in the case at bar bring it directly within the doctrine declared in the Massachusetts case, I have no doubt. The complainant, through its officers, explicitly states that the figures were adopted to distinguish its wares from those of other manufacturers, and it is difficult to perceive why such a number; “830,” was chosen, unless some such object was in view. If the design had simply been what the defendants insist it was, the figures 1, 2, 3, etc., would have suggested a more convenient and less perplexing method than the one actually adopted.

714It was the intention of the complainant to have its goods known in the market by these numerals; they were, in reality, so known. Not only is the fact sworn to in the complaint, but it is admitted in the answer at folio 22: the allegation being in the following language:

“And these defendants, further answering, severally say that they have been informed; and believe it to be true, and therefore admit, that such ‘Shawknit’ seamless half-hose of a mottled-drab color have been more generally known, called, and spoken of as ‘830's by dealers in hosiery than by any other name, and that under that designation such hose have sometimes been ordered, purchased, and sold.”

A very persuasive piece of evidence is found in an order produced by defendants, forwarded to them by their agent, in which these goods are described simply as “830, 2 doz.,” and in a bill, also produced by defendants, the same goods are charged to one of their customers as “2 doz. hose, 830, 2.40, $4.80.”

The right to use a trade-mark is one depending upon use, and it appears that complainant had used these numerals long enough to convey to any one versed in the nomenclature of the trade a precise understanding of what goods were intended when the numerals were used alone, disconnected from any extrinsic information.

I must hold, then, that the complainant has a right to the exclusive use on its labels of the numerals “830” as applied to hosiery of a mottled-drab color. Regarding the word “Shawknit,” printed in script letters, there is no denial of complainant's exclusive right.

The question that now remains to be considered is whether or not the defendants have infringed and invaded the rights and privileges of the complainant in such a manner as to call for interference of a court of equity. The intimate relations which had existed between complainant and defendants warranted the assumption on the part of the business community that the defendants were the agents of the Show Company, and could furnish the wares of that company upon terms as advantageous in every respect as the company itself. A merchant ordering “Shawknit” goods, or “830's,” from the Macks, would be less likely to scrutinize them with care, and more likely to accept them without thorough inspection, than if the same goods had been ordered from some irresponsible house. The seal of genuineness had been set on the goods furnished by Mack & Co. by the indorsement which the complainant had given them. Suspicion was disarmed, confidence invited.

715In these circumstances, the defendants, having on hand a large stock of the complainant's hosiery, purchased goods, cheaper, and certainly not superior, from a rival manufacturer, removed the maker's labels from both, and substituted therefor the label originated by themselves. They must have had some motive in doing this. What was it? The explanation in the letter of April 11th, that they wanted to find a substitute for complainant's retired stock, is hardly satisfactory, so far as the goods involved in this action are concerned; for in the last price list issued by complainant April 7, 1882, is found “830, mottled drab, 2.40,” still in stock. If the defendants intended to derive no benefit from the known reputation of the “Shawknit” goods—if they intended to sell the Birmingham goods solely on their merits—why would not some other number than 830 have suited them as well?

As is said by Judge Lowell in Rogers v. Rogers, 11 FED. REP. 495: “The reason that artificial trade-marks are absolutely protected, without inquiry into motives, etc., is that the defendant has no natural right to such a symbol, and has the world of nature from which to choose his own.” Is it not clear that defendants, occupying the relation they did to the complainant, by using the number “830” in connection with the word “seamless” placed in the same relative position, printed in the same script, and with the identical flourish as the word “Shawknit,” are in a position where, even though intending no wrong, their acts may work injury to the complainant? Are they not within the prohibition of the law, stated in such homely but vigorous language in Levy v. Walker, L. R. 10 Ch. D. 447:

“It should never be forgotten in these cases that the sole right to restrain anybody from using any name that he likes in the course of any business he chooses to carry on is a right in the nature of a trade-mark, that is to say, a man has a right to say, ‘You must not use a name, whether fictitious or real—you must not use a description, whether true or not, which is intended to represent, or calculated to represent, to the world that your business is my business, and so, by fraudulent mis-statement, deprive me of the profits of the business which would otherwise come to me.’”

It is well settled that one man has no right to sell his goods as those of another. Whether the converse of this proposition is also true—that a man has no right to sell another's goods as his own—it is unnecessary to decide in this case, as the question has not been discussed; and yet, according to defendants' version of the transaction, complainant's hosiery was sold by them as their own. It seems 716 to me that, irrespective of the question relating to the technical infringement of complainant's trade-mark, the defendants are in a position where they have gained, or may gain, an unlawful advantage in trade by means of a simulated label. It is hardly necessary to cite authorities where the courts have interfered for the protection of the injured in such cases.

In Fleischmann v. Schuckman, 62 How. Pr. 92, the defendant was restrained from using the word “Vienna,” as applied to bread, because the plaintiff had built up a business by so using it.

In Hier v. Abrahams, 82 N. Y. 519, defendants, using the words “Pride of Syracuse,” were enjoyed, the plaintiff using the words “Hier and Aldrich's Pride.”

Also the following: Knott v. Morgan, 2 Keene, 213; Edelsten v. Edelsten, 1 De G., J. & S. 185; Colman v. Crump, 70 N. Y. 573; Williams v. Spence, 25 How. Pr. 366.

I am therefore compelled to say, after carefully examining the evidence, and the elaborate briefs submitted, that in my judgment there is such a simulation as will probably deceive the complainant's customers. Great damage might result to the complainant by the continuance of defendants' label. I fail to see, however, how the defendants can be materially injured by its disuse. They are not manufacturers of hosiery, but are simply selling the productions of others. What legitimate profits can they lose by selling the goods as they come from the manufactory with the original labels attached?

I think an injunction should issue restraining the defendants from using the numeral “830” to designate mottled-drab hose not made by complainant, and from using on their labels the word “seamless” printed in script, with the flourish underneath in imitation of the word “Shawknit,” as used by complainant.

Motion granted.

See Burton v. Stratton, ante, 696, and note.

717NOTE.

TRADE-MARK. A trade-mark may consist of anything—marks, forms, words, signs, symbols, or devices—designating origin or ownership, but not anything merely denoting name or quality;(a) and a manufacturer may by priority of appropriation acquire a property therein as a trade-mark.(b) All the essential requisites to the right of protection of law arises from prior use of the device which has created a celebrity or value for the article;(c) and the mark or device should be annexed to or stamped, printed, carved, or engraved upon the article;(d) and when stamped upon the articles manufactured by him he is entitled to its exclusive use.(e) It must be such a mark as will identify the article to which it is affixed.(f) So the omission to put the advertising name “Moline plow” on their plows divests the company of its exclusive right to the use of “Moline.”(g)

One may appropriate an arbitrary number as a valid trade-mark, although not using it in connection with any word signifying ownership.(h) Letters or figures affixed to merchandise for the purpose of denoting its quality only cannot be appropriated;(i) but the words on labels “established 1780,” which had been long used, were held entitled to protection.(j) So injunction was granted to restrain the use of the trade-mark “The Shirt,”(k) or the symbol ½ printed in a special or unusual manner, (l) or numerals associated with words, as “303” with words “Joseph Gillott, extra fine.” (m) A street number may be appropriated by one who has exclusive use of the building.(n)

SIMILITUDE. Putting up goods with an infringing mark will render the party so doing liable, (aa) as the use of similar packages with the same words and figures embossed thereon. (bb) The peculiar style of the package in which the article is put up, and the combination constituting the label, is protected;(cc) as the use of a barrel with a red rim and glazed head, with the letters AAA and a Maltese cross. (dd) Any labels, devices, or hand-bills calculated to deceive the public into the belief that the article is the same as that made and sold by the plaintiff is an infringement. (ee) In all cases the essence of the wrong consists in the sale of the goods of one person as those of another,(ff) and the true inquiry is whether the marks or symbols actually deceive the public.(gg) Simulated labels, marks, indicia, or advertisements 718 such as would ordinarily deceive customers, will be enjoined;(h) or where the imitation would have the effect to pass the goods as those of another with any one but the most cautious;(i) or where the resemblance would raise the probability of mistake on the part of the public.(j) The words, letters, figures, lines, and devices on a label must be so similar that any person, with such reasonable observation as the public generally are capable of, would mistake the goods for those of the other.(k) The imitation need not be exact and complete;(l) it is sufficient if it is likely to deceive or mislead(m) an ordinary purchaser.(n) The resemblance must amount to a false representation liable to deceive,(o) or if it is so close that a crafty vendor may palm off on the buyer the article manufactured as that of the other.(p) If the general effect is to mislead an ordinary person it is sufficient,(q) or if calculated to mislead the public, though the distinction between the imitation and the original would at once be seen on a slight or casual examination.(r) If it is a colorable representation of plaintiff's label, calculated to produce in the mind of the purchaser the impression that the goods were manufactured or sold by the person whose trade-mark was imitated, it is sufficient.(s) A colorable imitation will be enjoined where it requires careful inspection to distinguish it from the original,(t) and a substantial similarity is sufficient;(u) or where the difference would not be noticed when seen at different times and places.(v) An imitation with partial differences, such as the public would not observe,(w) or which would not be perceived without strict examination, will not protect it from injunction(x) and should be disregarded;(y) but if the alleged imitation has not deceived an ordinary purchaser an injunction will not be granted.(z) Where the name of the imitator was substituted in a label, and the imitation in other respects not exact. Yet so great that a purchaser, who did not read the name, might be deceived, it is a violation of the trade-mark.(a) So the use of the word “Apollinis” on a label, in connection with a representation of a bow and arrow or anchor, was restrained on account of similarity to the word “Apollinaris” with the representation of an anchor.(b) An article of the same kind, called “Saphia,”put up in similar wrappers as the article called “Sapolio,” the imitation being intended to deceive, should be restrained.(c) A trade-mark, “The Rising Sun,” with a vignette of the sun, is not infringed by the words “Rising Moon,” with a vignette of the moon.(d)

719PROTECTION OF RIGHT. The doctrine of protection of trade-marks is based upon the broad principle of protecting the public from deceit;(a) and injunction will be granted to restrain its practical use;(b) but to authorize an injunction plaintiff's title to its exclusive use should be clear and unquestionable,(c) and be clearly established.(d) The legal right of plaintiff and violation by defendant must be clear.(e) A person having appropriated to himself a particular label, sign, or trade-mark is entitled to the protection thereof, and the courts will enjoin their use without authority,(f) unless he has acquiesced in its use by a third party.(g) If the representation of the trade-mark does not mislead the public, and is substantially true, it will be entitled to protection.(h) A party may be restrained from the use of his own name in business, if he uses it for the purpose of deception;(i) or so as to appropriate the good-will of a business established by others of that name.(j) —[ED

(a) Godillot v. Hazard, 49 How. Pr. 5; Ferguson v. Davol Mills, 2 Brewst. 314.

(b) Stokes v. Landgraff, 17 Barb. 608; Robertson v. Berry, 50 Md. 591; Trade-Mark Cases, 100 U. S. 82.

(c) Messerole v. Tynberg. 36 How Pr. 141.

(d) St. Louis Piano Manuf'g Co. v. Merkel, 1 Mo. App. 305.

(e) Taylor v. Carpenter. 11 Paige, 292.

(f) Phalon v. Wright, 5 Phila. 464.

(g) Candee v. Deere, 54 Ill. 439.

(h) Collins v. Reynolds Card Manuf'g Co. 7 Abb. N. C. 17; India Rubber Co. v. Rubber, etc., Co. 45 N. Y. Super. 258; Lawrence Manuf'g Co. v. Lowell H. Co. 129 Mass. 125.

(i) Amoskeag Manuf'g Co. v. Trainer, 101 U. S. 51; Sohl v. Geisendorf, 1 Wils. (Ind.) 60.

(j) Hazard v. Caswell, 57 How. Pr. 1.

(k) Morrison v. Case, 9 Blatchf. 548.

(l) Kinney v. Allen, 1 Hughes, 106.

(m) Gillott v. Esterbrook, 48 N. Y. 374; 47 Barb. 455; Same v. Kettle, 3 Duer, 624.

(n) Glen, etc., Co. v. Hall, 6 Lans. 158. But the use of IXL as a sign was refused protection. Lichtenstein v. Mellis, $$ Or. 464..

(aa) Sawyer v. Kellogg, 13 Rep. 196.

(bb) Frese v. Bachof, 14 Blatchf. 432.

(cc) Cook v. Starkweather, 13 Abb. Pr. 393; Lea v. Wolf, Id. 391.

(dd) Cook v. Starkweather, 13 Abb. Pr. 392.

(ee) Williams v. Spence, 26 How. Pr. 366.

(ff) Amoskeag Manuf'g Co. v. Spear, 2 Sandr. 599; Samuel v. Berger, 4 Abb. Pr. 88.

(gg) Blackwell v. Wright, 73 N. C. 10.

(h) Tallcot v. Moore, 13 N. Y. Super. 106.

(i) Brooklyn White L. Co. v. Masury, 25 Barb 416.

(j) McCartney v. Garnhart, 45 Mo. 593.

(k) Gilman v. Hunnewell, 122 Mass. 139.

(l) Hostetter v. Vowinkle, 1 Dill. 329; Filley v. Fassett, 44 Mo. 168.

(m) Filley v. Fassett, 44 Mo. 168; Hostetter v. Vowinkle, 1 Dill. 329; Robertson v. Berry, 50 Md. 591; Leidersdorf v. Flint, 50 Wis. 401.

(n) Lockwood v. Bostwick, 2 Daly, 521.

(o) Popham v. Cole, 66 N. Y. 69; Osgood v. Allen, 1 Holmes, 185. The intent to deceive is sufficient. McLenn v. Fleming, 96 U. S. 245.

(p) Brown v. Mercer, 37 N. Y. Super. 265.

(q) Hostetter v. Adams, 10 Fed. Rep. 838.

(r) Popham v. Wilcox, 14 Abb. Pr. (N. S.) 206.

(s) Burke v. Cassin, 45 Cal. 467.

(t) Partridge v. Menick, 2 Sandi. Ch. 622.

(u) Bradley v. Norton, 33 Conn. 157.

(v) Sohl v. Geisendorf, 1 Wils. (Ind.) 60.

(w) Clark v. Clark, 25 Barb. 76.

(x) Williams v. Johnson, 2 Bosw. 1.

(y) Laird v. Wilder, 9 Bush, 131.

(z) Hurricane Lantern Co. v. Miller, 56 How. Pr. 234.

(a) Boardman v. Meriden Brit. Co. 35 Conn. 402.

(b) Apollinaris Brunnen v. Somborn, 14 Blatchf. 380.

(c) Enoch Morgan's Sons' Co. v. Schwachofer, 5 Abb. N. C. 265. See Same v. Troxell, 57 How. Pr. 121.

(d) Morse v. Worrell, 10 Phila. 168.

(a) Matsell v. Flanagan, 2 Abb. Pr. (N. S.) 459.

(b) Rowley v. Houghton, 7 Phila. 39.

(c) Ellis v. Zeilin, 42 Ga. 91.

(d) Wolfe v. Goulard, 18 How. Pr. 64; Corwin v. Daly, 7 Bosw, 222; Coffeen v. Brunton, 5 McLean, 256.

(e) Merrimack Manuf'g Co. v. Garner, 2 Abb. Pr. 318; Fetridge v. Merchant, 4 Abb. Pr. 156; Samuel v. Berger, Id. 88; Partridge v. Menck, 2 Barb. Ch. 101.

(f) Collady v. Baird, 4 Phila. 139; Coats v. Holbrook, 2 Sandf. Ch. 586; Taylor v. Carpenter, Id. 603.

(g) Delaware, etc., Canal Co. v. Clark, 7 Blatchf. 112; Caswell v. Davis, 58 N. Y. 223; Filley v. Child, 16 Blatchf. 376; McLean v. Fleming, 96 U. U. S. 246.

(h) Meriden Brit. Co. v. Parker. 39 Conn. 450.

(i) Decker v. Decker, 52 How. Pr. 218. Consuit Benninger v. Wattles, 28 How. Pr. 286; Holloway v. Holloway, 13 Beav. 209; Clark v. Clark, 25 Barb. 76; Stonebraker v. Stonebraker, 33 Md. 252; Devlin v. Devlin, 67 Barb. 290; Rogers v. Nowill, 6 Hare, 325; Holmes v. Holmes, 37 Conn. 278; Comstock v. White, 18 How. Pr. 421; Faber v. Faber, 49 Barb. 357; McLean v. Fleming, 96 U. S. 246; Probasco v. Boyon, 1 Mo. App. 241.

(j) William Rogers Manuf's Co. v. Rogers, etc., Co. 11 Fed. Rep. 495. See Gillis v. Hall, 7 Phila. 422; Ainsworth v. Bentley, 14 Week. Rep. 630.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Nolo.