PEPPER v. LABROT and another.*

Circuit Court, D. Kentucky.

July, 1881.

v.8, no.1-3

1. TRADE-MARK—“OLD OSCAR PEPPER DISTILLERY”—DESCRIPTIVE OF PLACE OF MANUFACTURE—SALE OF PREMISES—RIGHT OF PURCHASER TO TRADE-MARK.

The complainant, in 1874, was the owner by inheritance, of a tract of land on which his father, during his life-time, for many years had carried on a distillery, manufacturing whisky, which, from the name of the distiller, became known as “Old Crow Whisky,” and the distillery as Oscar Pepper's Old Crow Distillery. The complainant erected a new distillery and manufactured whisky, branding on the heads of the barrels “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery; Hand-made Sour Mash; James E. Pepper, Proprietor, Woodford County, Ky.,” and used the same as a trade-mark in circulars, bill-heads, letter-heads, etc. Subsequently the complainant became bankrupt, and his distillery premises, buildings, machinery, etc., were sold by his assignee under the name of the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery,” and became the property of the defendants, who operated the same by the manufacture of whisky, using the trade-mark adopted by the complainant, substituting their own names as proprietors. A bill was filed by complainant to enjoin the use of the trade-mark, the defendants filing a cross-bill asking to be protected in their claim to its exclusive use.

Held, (1) that the trade-mark was a description of the place of manufacture, and did not designate, either expressly or by association, the personal origin of the product.

(2) That the complainant, having ceased to be the owner of the distillery and proposing to use the name on whisky to be manufactured elsewhere, had no right to the exclusive use of the trade-mark as against the defendants, who could use it as a truthful description of their own production.

(3) That the complainant had no right to use it at all, because to do so would be to deceive and mislead the public by a false representation in respect to the place of the manufacture of his goods.

(4) That the defendants, by virtue of their ownership of the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery, succeeded to the exclusive right to use that name for their premises and place of manufacture, and to brand it on the packages of their merchandise for the purpose of truly indicating it as a product of a distillery well known by that name.

In Equity. Trade-mark. Bill for injunction and account, and cross-bill for injunction. Final hearing upon pleadings and proofs.

Barrett & Brown and John Marshall, for complainant.

1. Complainant's trade-mark embodied his family name, and was therefore peculiarly appropriate. See Ainsworth v. Walmesly, 44 L. J. 252. The right to use the name passed from father to son as a personal right, not as a chattel real. See Dixon Crucible Co. v. Guggenheim, Cox's Trade-mark Cas. 577.

2. Did the trade-mark pass to the assignee in bankruptcy and from him to defendants by their purchase? A general assignment under state laws does not carry a trade-mark. Bradley v. Norton, 33 Conn. 157. Vendee in bankruptcy acquires no right as against bankrupt to a trade-mark which he used to designate his own preparations. Hembold v. Hembold Co. 53 How. Pr. 453.

303. Conveying the distillery as the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery” did not give defendants a right to use the term as descriptive of their whisky. Dixon Crucible Co. v. Guggenheim, Cox's Trade-mark Co. 577; Howe v. Searing, Id. 244; McArdle v. Peck, Id. 312; Woodward v. Lazar, Id. 300. By purchasing the realty, the vendee does not acquire the right to trade-marks used upon it, and one may use his trade-mark in a new place, though it was local in its original significance. Wotherspoon v. Currie, 23 L. T. Rep. 443; 5 E. & I. App. 508.

W. Lindsay, for defendants, cited—

Leather Cloth Co. v. Am. Leather Cloth Co. Cox's Am. Trade-mark Cas 704; Congress Spring Co. v. High Rock Congress Spring Co. Id. 630; Kidd v. Johnson, 100 U. S. 620; G. & H. Manuf'g. Co. v. Hall, 61 N. Y. 229; Carmichael v. Lattimer, 11 R. I. 407; Hall v. Barrows, 4 De Gex, Jones & Smith, 151; Booth v. Jarrett, 52 How. Pr. 169; Canal v. Clark, 13 Wall. 325, referred to in Mr. Justice Matthews' opinion; and also Llewellen v. Rutherford, 49 Barb. 588; Newman v. Alford, 49 Barb. 588.

Before Mr. Justice MATTHEWS and BARR, D. J.

MATTHEWS, Circuit Justice. This is a bill in equity filed October 23, 1880, the complainant being a citizen of the state of New York, and the defendants citizens of Kentucky.

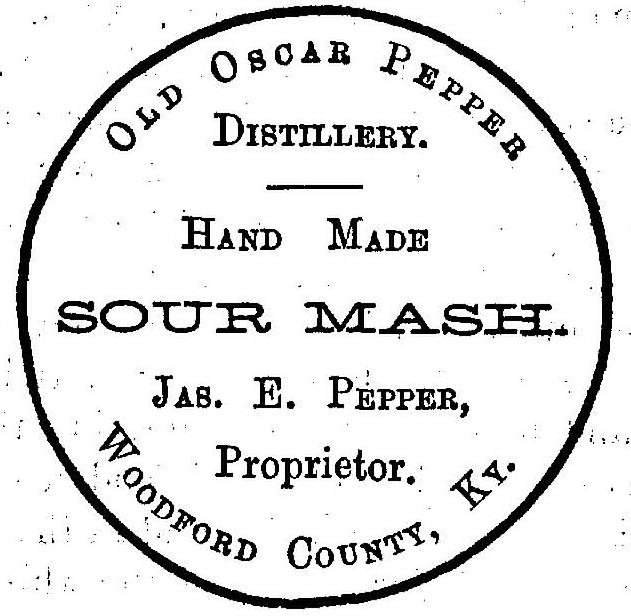

It is alleged that both parties are, and have been, engaged in the manufacture and sale of whisky. The complainant claims to be the originator, inventor, and owner of a certain trade-mark and brand for whisky make by him, consisting of the words “Old Oscar Pepper,” and also of an abbreviation thereof, consisting of the letters “O. O. P.” He alleges that the said words and letters were and are a fanciful and arbitrary title and trade-mark and brand intended to designate and identify whisky of his manufacture, the use of which he began in 1874, continued since by branding and marking the words on each barrel, and using the letters as an abbreviation in correspondence and contracts concerning the article; the whisky so designated having acquired that name, and being well and favorably known thereby. He says that the said words and trade-mark were made up in fact of the family name of the complainant, and embodied the name of his father, and had never before been so used. He avers that the whisky made by him, and so branded, marked, and known, was very carefully manufactured, and of excellent quality, and of great reputation in the market, commanding a ready sale at profitable prices, and was identified by said trade-mark as of the complainant's make, whereby the said trade-mark has became of great value to him. He alleges that the trade-mark, “Old Oscar Pepper,” was used by him by burning the same upon and into the heads of barrels containing whisky 31 made by him, in a form set out as an exhibit to the bill. A copy is here set out as follows:

The same device on a smaller scale was printed upon the letter heads and bill heads and business cards used by him in correspondence, and other business, concerning his whisky; and was also attached to and pasted upon all small packages and samples of the whisky made by him, and was used to identify, and was universally recognized as identifying, the whisky made by him.

On November 13, 1877, the complainant procured a certificate of the registration of said trade-mark under the laws of the United States.

The bill charges that the defendants have sought to appropriate the complainant's trade-mark to their own use, and are using, upon barrels of whisky made by them, a similar device, a copy of which is exhibited. It is as follows:

It is alleged that this is done by the defendants with the wrongful 32 and fraudulent design to procure the custom and trade of persons who are or have been in the habit of buying, vending, or using the genuine whisky made by the complainant, and of illegally and fraudulently promoting the introduction and sale of the defendants' own whisky, under the cover and reputation of the complainant's trademark, and of inducing unsuspecting persons to purchase the whiskies of defendants as and for the genuine “Old Oscar Pepper” whisky, manufactured by the complainant. It is charged, also, that with like intent the defendants are using the same device and trade-mark upon their letter-heads, and business cards, and other papers and advertisements, and upon packages containing their whisky. It is also charged that this conduct of the defendants is injurious to the complainant in the sale of his whisky, and in the profits thereof, and that, by reason of the inferior quality of the whisky sold by defendants under such trade-mark, the reputation of the complainant's whisky is greatly prejudiced and injured in the markets of the country, and a fraud and deception practiced upon the public, many of whom are induced to purchase the defendants' whisky, believing it to be the manufacture of the complainant.

The bill accordingly prays for an injunction and an account.

The defendants filed an answer in which they admit that they have been and are engaged in manufacturing and selling whisky, their distillery being in Woodford county, Kentucky, and long known and designated as the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery.” They deny that the complainant is the originator or owner of the trade-mark or brand for whisky made by him, as claimed, and deny that the words “Old Oscar Pepper,” or the abbreviation of them, by the letters “O. O. P.,” have ever been used as an arbitrary or fanciful title or trade-mark for whisky, or that they were ever so used by the complainant, and allege that they were never used by him except in connection with the word “distillery,” and then only for the purpose of showing that the whisky in reference to which they were so used was manufactured at and was the product of the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery. The defendants claim that the use of the same by the complainant as a brand for their whisky, manufactured elsewhere, would be a fraud on the public, as well as on the defendants. They say that several years since the complainant became the owner of 33 acres of land in Woodford county, Kentucky, known as the land used by Oscar Pepper for distillery purposes, upon which there was a distillery, and machinery, warehouse, and other improvements; that said distillery, during the life-time of Oscar Pepper, the father 33 of the complainant, became famous because of the superior quality of the whisky there produced, which was attributed, by dealers in whisky, to the peculiar character and properties of the water used in the process of distillation; that in 1874 the complainant, in company with one E. J. Taylor, Jr., with whom he was associated in business, operated said distillery, and formally named it the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery,” and procured a large number of iron signs to be made and distributed throughout the country, containing a correct drawing of the distillery and warehouse building, and an accurate view of the old Oscar Pepper homestead or dwelling, which drawing and view they surrounded with the words, in a circular form, above the same, “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery,” and below, in a straight line, “Woodford Co., Kentucky,” and thus, as is claimed, fixed and determined the name of said distillery. They also procured an iron brand to be made, and with it burnt into the head of each barrel of whisky, manufactured in said distillery, the words—

Old Oscar Pepper

Distillery.

Hand-made Sour Mash.

James E. Pepper,

Proprietor,

Woodford County, Ky.,

—for the purpose, as is alleged, of identifying it as the product of the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery. It is also alleged that the complainant advertised his business in a circular, as follows:

“Having put in the most thorough running order the old distillery premises of my father, the late Oscar Pepper, (now owned by me,) I offer to the first-class trade of this country a hand-made, sour-mash, pure copper whisky of perfect excellence. The celebrity attained by the whisky made by my father was ascribable to the excellent water used, (a very superior spring,) and the grain grown on the farm adjoining by himself, and to the process observed by James Crow, after his death by William F. Mitchell, his distillers. I am now running the distillery with the same distiller, the same water, the same formulas, and grain grown upon the same farm.”

He also circulated a similar certificate from his distiller, Mitchell, who said:

“I am employed by James E. Pepper as distiller, and the whisky I now make is from the same formula as the celebrated Crow whisky manufactured by James Crow and myself for his father, (the late Oscar Pepper,) at the same place, and is of the same excellence, being identical in quality. I use the same water, the same grain, the same still.”

It is also alleged that the complainant, in March, 1877, was declared 34 a bankrupt, and that among other assets the tract of land and the distillery thereon, with all the appurtenances and fixtures, were sold by the assignee, and by mesne conveyances became vested in the defendants, who have since operated the same by the manufacture of whisky; and that the complainant in the mean time has been, and is now, operating a distillery in Fayette county, Kentucky, as the sole place of the manufacture of his whisky, and that consequently he cannot use the brand formerly used by him while operating the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery,” without making a false and fraudulent representation as to the place of manufacture.

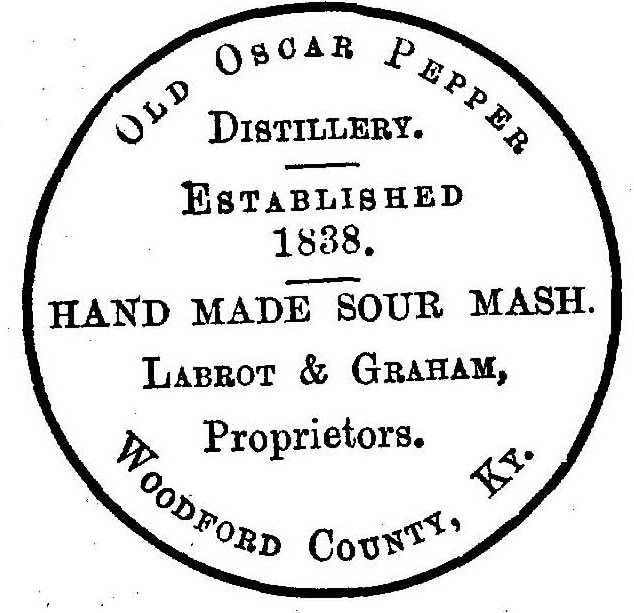

The defendants admit that since they have owned and operated the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery, they have used the brand set out in the pleadings, but merely for the purpose of identifying their whisky as the product of that distillery, as follows:

Old Oscar Pepper

Distillery.

Established 1838.

Hand-made Sour Mash.

Labrot & Graham,

Proprietors,

Woodford County, Kentucky.

They claim the right so to do by virtue of their ownership of the distillery, of which they say that is the proper name.

On November 23, 1880, the defendants also filed their cross-bill, setting up in substance the same facts, and claiming that they are entitled to the exclusive use as a trade-mark of the brand described in the pleadings as used by them, and praying to be protected therein by a perpetual injunction.

To this cross-bill the complainant filed his answer, insisting upon his claims to the injunction and right to the exclusive use of the trade-mark, “Old Oscar Pepper,” and the abbreviation “O. O. P,” as applied to whisky. He alleges that his father, during his life-time, Oscar Pepper, operated a distillery on the premises mentioned, and manufactured an article which became well and favorably known to the trade as “Crow” or “Old Crow” whisky, from the name of the distiller, and that in consequence the distillery became known as the “Old Crow Distillery;” that after his father's death, the distillery tract having come into his possession, he leased it to W. A. Gaines & Co., who continued the manufacture of whisky under the same trade-name and mark of “Crow,” or “Old Crow,” but that afterwards the complainant, having gone into the business himself, built on the same 35 site an entirely new distillery, and manufactured whisky which he called by the name of “Old Oscar Pepper,” and so marked and branded the packages, and thereby originated and adopted it as his trade-mark to identify and distinguish the whisky made by him, and it became well and favorably known as such. He says that in the manufacture of his whisky he used neither the same distillery building at which the “Crow” whisky was manufactured, nor the identical spring of water which had been used in connection with it, but another spring in the same vicinity of the same quality; all the springs of water in the same geological formation throughout the counties of Woodford, Fayette, Bourbon, Harrison, and the blue-grass section of Kentucky being substantially alike in quality, and the whisky made from one indistinguishable from that made, with equal care and skill and by the same process, at any other.

And the complainant insists that the name “Old Oscar Pepper” was never applied to the distillery premises until after he had adopted it as the name of whisky made by him, and then only as indicating the place where he made his “Old Oscar Pepper” whisky; and that it was not the name of the distillery which was applied to designate the whisky made there, but the name of the whisky which was applied to designate the distillery at which it was made, so far as it was ever so known or called. He charges that the use by the defendants of the words “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery,” as descriptive of the locality, is a subterfuge their make of whisky, and thereby wrongfully to use complainant's trade-mark and pirate his trade.

General replications perfect the issue arising both on the original and cross-bills, and the cause has been submitted on final hearing upon the pleadings and proofs.

It is manifest that the controversy between the parties, in the first instance, is one of fact.

The construction of the complainant is, that the words “Old Oscar Pepper” and the abbreviation of them, “O. O. P.,” constitute a brand or mark originally adopted by him to designate whisky as made by him, without reference to the place of manufacture; and that by use and recognition it has become associated in the minds of dealers and the public with the article manufactured by him, so as to constitute its name in the trade, whereby to distinguish it from a similar article made by any and all others.

On the other hand, the defendants claim that the words in question were originally used, and their use subsequently continued, merely 36 to designate the fact that the whisky contained in the packages so marked or spoken of in advertisements, circulars, signs, etc., on which the mark was burned or printed, was made at the distillery so designated; and that that was done because the distillery, or its predecessor on the same site, had acquired a reputation in connection with the manufacture of whisky which was sufficient to recommend any article made at the same place.

Undoubtedly the inference, from the plain meaning of the words themselves, supports strongly the claim on the part of the defendants.

The complainant's brand or mark, as claimed and used by him, is “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery, Woodford Co., Ky.,” James E. Pepper, proprietor; the words “hand-made sour mash” describe the quality of the whisky; and as to the rest, the plain and unequivocal meaning is that it is the product of the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery,” of which James E. Pepper is proprietor.

The complainant in his testimony endeavors to explain his use of the word “distillery” in this connection, so as to make its use consistent with his claim that the words “Old Oscar Pepper” were intended to designate the whisky and not the distillery. He says: “In branding the ends of my barrels, I put the word ‘distillery’ to show that the ‘Old Oscar Pepper’ whisky was a straight whisky made by me, and at my own distillery, and not a compounded whisky; and the use of the word ‘distillery,’ on the heads of the barrels following the trade-mark, indicated a straight whisky as distinguished from a compounded whisky.”

But the explanation does not seem sufficient. The use of the word “distillery” does, indeed, seem to advertise the fact that the whisky is distilled, and not rectified, but it does so by designating the spirits contained in the package as the product, not merely of a distillery, but of the particular distillery known as the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery,” of which James E. Pepper is proprietor.

It is true that Beecher, one of the firm of Ives, Beecher & Co., the merchants who sold the complainant's whisky in New York, testifies that the whisky acquired its reputation under the name of “Old Oscar Pepper” or “O. O. P.” whisky, and known by that name, and inquired after and bought and sold by that designation. He says my firm buy whisky under the name of “Old Oscar Pepper.” But he immediately explains that “we buy as ‘Old Oscar Pepper,’ whisky to be made at the distillery where James E. Pepper first made the whisky known to the trade by that name.” (Answer to the twentythird 37 interrogatory.) And in answer to the seventh cross-interrogatory he says:

“At the time my firm commenced dealing in ‘Old Oscar Pepper’ whisky, that name added to the reputation and salability of the whisky, for the reason that that was the name of James E. Pepper's father, and his father had made good whisky at that very distillery for several years previous to the making of any by James E. Pepper.”

It is beyond dispute that Ives, Beecher & Co. introduced the complainant's manufacture of whisky to the trade under the name of Old Oscar Pepper whiskies, upon the credit of the old distillery of Oscar Pepper, and recommended them as of superior excellence because they were the product of that distillery. This was done by advertisements in circulars, containing certificates and affidavits, one from James E. Pepper himself, that he had put in the most thorough running order “the old distillery of my father, the late Oscar Pepper, now owned by me;” that “the celebrity attained by the whiskey made by my father was ascribable to the excellent water used (a very superior spring) and the grain grown on the farm adjoining by himself, and to the process observed by James Crow, after his death by W. F. Mitchell, his distillers;” that “I am now running the distillery with the same distiller, the same water, the same formula, and grain grown upon the same farm, consequently my product being of the same quality and excellence.” Another certificate and affidavit so published was from his mother, in which she stated that her son, James E. Pepper, is the owner of the old distillery property situated in the county of Woodford, state of Kentucky, formerly owned by her deceased husband, Oscar Pepper, and known as the “Old Crow Distillery:”

“The buildings have been thoroughly improved. Mr. W. F. Mitchell, who distilled for the late Oscar Pepper, succeeding James Crow, is employed by my son, and the product is of the highest excellence, and recognized as fully up to the standard of the celebrated old product from the same stills.”

And the distiller, Mitchell, also certifies: “I use the same water, the same grain, and the same STILL.”

It does not avail the complainant now to repudiate these representions, or to insist that they are altogether immaterial. It may be true, as he now says, that in point of fact his distillery was altogether distinct as a building and machinery from that so long operated by his father, and that he did not use the same spring of water and the same stills; and it may be equally true that, so far as the intrinsic quality of the whisky is concerned, the circumstances referred to 38 were altogether unimportant, for the reason that the product of equally good materials, made in the same geological region, in the best manner known to those engaged then in the manufacture, could not be distinguished from the favorite article known by the name of any particular distillery. Nevertheless, it remains quite certain, from the proofs in this case, that the complainant succeeded in establishing a market for his manufacture, upon the special belief of the public that it must be like that made by his father, because made at the same locality and with all the advantages it was thought to confer. In other words, he sought and obtained for his own manufacture, by the use of the name of his father's distillery, the reputation established by Oscar Pepper for his own.

Oscar Pepper manufactured at his distillery for many years previous to his death in 1865, probably as early as 1838, and the distillery was known in the neighborhood, as some witnesses testify, as Oscar Pepper's distillery. This, indeed, would be most natural. Afterwards, the whisky distilled there under the management of James Crow became extensively and favorably known as “Old Crow” whisky, and the distillery acquired the name of the Old Crow Distillery; and that name was used after the death of Oscar Pepper, by successive lessees of the establishment, as a trade-mark to designate its production; but during that period the name of Oscar Pepper, as formerly connected with it, appeared in the brands and marks used by Gaines, Berry & Co. while they were carrying it on. They styled themselves on business cards “Lessees of Oscar Pepper's ‘Old Crow’ Distillery.” In 1874 the trade-mark of “Old Crow” having previously, by Gaines, been transferred to the product of another distillery owned or operated by him or his firm, the complainant came into possession of his own distillery, and it became known as the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery.” The deed directly to the complainant of the distillery premises, made by a commissioner in pursuance of a decree for partition, refers to an accompanying plat in which the “Old Crow Distillery” is designated; but early in 1875 an agreement was made by the complainant with one E. H. Taylor, Jr., reciting that the former was owner of the premises upon which is situate the old distillery, which was operated and run by the said Oscar Pepper in his life-time, and providing means for a thorough reparation of said old distillery, and of operating the same for the purpose of manufacturing copper whisky of the grade, character, and description of that which was made by the said Oscar Pepper in his life-time, when James Crow and W. F. Mitchell were his 39 distillers. The complainant having, upon his own petition, been declared a bankrupt, filed the required schedule of his assets and liabilities, in which he described the tract of land inherited from his brother as including the “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery;” and as such it was known at the time the title became vested in the defendants.

The clear result of the whole evidence seems, in our opinion, to be that the complainant adopted the name of “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery” as the name of his distillery, in order that the whisky manufactured by him there might have the reputation and whatever other advantages were to result from that association.

That distillery having now become the property of the defendants by purchase from the complainants, can they be denied the right of using the name by which it was previously known in the prosecution of the business of operating it, and of describing the whisky made by them as its product?

Can the complainant be permitted to use the brand or mark formerly employed by him, to represent whisky made by him elsewhere as the actual product of this distillery?

Both these questions, in our opinion, must be answered in the negative.

The most-recent statement of the law applicable to this subject by the supreme court of the United States is found in the case of The Amoskeag Manuf'g Co. v. Trainer, 101 U. S. 51. In that case Mr. Justice Field said:

“The general doctrines of the law as to trade-marks, the symbols or signs which may be used to designate products of a particular manufacture, and the protection which the courts will afford to those who originally appropriated them, are not controverted. Every one is at liberty to affix to a product of his own manufacture any symbol or device not previously appropriated, which will distinguish it from articles of the same general nature manufactured or sold by others, and thus secure to himself the benefit of increased sales by reason of any peculiar excellence he may have given to it. The symbol or device thus becomes a sign to the public of the origin of the goods to which it is attached, and an assurance that they are the genuine article of the original producer. In this way it often proves to be of great value to the manufacturer in preventing the substitution and sale of an inferior and different article for his products. It becomes his trade-mark, and the courts will protect him in its exclusive use, either by the imposition of damages for its wrongful appropriation, or by restraining others from applying it to their goods, and compelling them to account for profits made on a sale of goods marked with it. The limitations upon the use of devices as trade-marks are well defined. The object of the trade-mark is to indicate, either by its own meaning or by association, the origin or ownership of the article to which it is applied. If it did not, it would serve no useful purpose either to the manufacturer or to 40 the public. It would afford no protection to either against the sale of a spurious in place of the genuine article. This object of the trade-mark, and the consequent limitations upon its use, are stated with great clearness in the case of Canal Co. v. Clark, 13 Wall. 1. There the court said, speaking through Mr. Justice Strong, that no one can claim protection for the exclusive use of a trade-mark or trade-name which would practically give him a monopoly in the sale of any goods other than those produced or made by himself. If he could, the public would be injured rather than protected, for competition would be destroyed. Nor can a generic name, or a name merely descriptive of an article of trade, of its qualities, ingredients, or characteristics, be employed as a trade-mark, and the exclusive use of it be entitled to legal protection.”

In the case of Canal Co. v. Clark, 13 Wall. 322, it is stated that the—

“Office of a trade-mark is to point out distinctively the origin or ownership of the article to which it is affixed; or, in other words, to give notice who was the producer.”

And that there are some limits to the right of selection will be manifest. It is further said, in that case:

“When it is considered that in all cases where rights to the exclusive use of a trade-mark are invaded it is invariably held that the essence of the wrong consists in the sale of the goods of one manufacturer or vendor as those of another; and that it is only when this false representation is directly or indirectly made that the party who appeals to a court of equity can have relief. This is the doctrine of all the authorities.”

“And it is obvious that the same reasons,” continues the opinion in that case, “which forbid the exclusive appropriation of generic names, or of those merely descriptive of the article manufactured, and which can be employed with truth by other manufacturers, apply with equal force to the appropriation of geographical names designating districts of country. Their nature is such that they cannot point to the origin (personal origin) or ownership of the article of trade to which they may be applied. They point only at the place of production, not to the producer, and could they be appropriated exclusively the appropriation would result in mischievous monopolies.”

In the same opinion, Mr. Justice Strong quoted, with approval, an extract from the opinion in the case of the Amoskeag Manuf'g. Co. v. Spear, 2 Sandford, Sup. Ct. 509, as follows:

“The owner of an original trade-mark has an undoubted right to be protected in the exclusive use of all the marks, forms, or symbols that were appropriated as designating the time, origin, or ownership of the article or fabric to which they are affixed; but he has no right to the exclusive use of any words, letters, figures, or symbols which have no relation to the origin or ownership of the goods, but are only meant to indicate their names or quality. He has no right to appropriate a sign or a symbol, which, from the nature of the fact it is used to signify, others may employ with equal truth, and therefore have an equal right to employ for the same purpose.”

41Following and applying the principle expressed in the last sentence of this extract, Mr. Justice Strong, in the opinion from which we are still quoting, says:

“It is only when the adoption or imitation of what is claimed to be a trademark amounts to a false representation, express or implied, designed or incidental, that there is any title to relief against it. True, it may be, that the use by a second producer, in describing truthfully his product, of a name or a combination of words already in use by another, may have the effect of causing the public to mistake as to the origin or ownership of the product; but if it is just as true in its application to his goods as it is to those of another who first applied it, and who, therefore, claims an exclusive right to use it, there is no legal or moral wrong done. Purchasers may be mistaken, but they are not deceived, by false representations, and equity will not enjoin against telling the truth.”

Tried by these principles, it would seem that the trade-mark claimed by the complainant cannot be sustained as a designation of whisky manufactured by him without reference to the place of its production, and that it is not, therefore, a lawful trade-mark at all, in the proper sense of that term. It is rather the trade-name of the distillery itself, of which he was at one time the proprietor, but which now is the property of the defendants. Neither by its own meaning, nor by association, does it indicate the personal origin or ownership of the article to which it is affixed. It does not seem to give notice who was the producer. It could be applied by him, with truth, to his goods only while he was the owner of the distillery named, and then only, not to all whisky of his manufacture, but only to that actually produced at that distillery. It can now be used without practicing a deception upon the public only by the defendants. It points only at the place of production, not to the produce. If a trade-mark at all, in any lawful sense, it is only in its use in connection with the article which it truthfully describes; that is, whisky which is actually manufactured at the Old Oscar Pepper Distillery, in Woodford county.

In the case of Hall, v. Barrows, 4 De Gex, Jones & Smith, 157, there was a trade-mark altogether distinct from the name of the works, being the initials of the names of two of the original firms which owned the works, stamped upon the iron produced at the works. The question was whether, in a sale of the works and business to a surviving partner, the trade-marks should be valued as passing in the sale. The Lord Chancellor, Westbury, said:

“There is nothing in the answer or evidence to show that the iron marked with these initials has, or ever had, a reputation in the market because it was believed to be the actual manufacture of one of the two original firms.

42Now, if I adopted the distinction drawn by the master of the rolls between local and personal trade-marks, I should be more inclined to treat this mark as incident to the possession of the Bloomfield Iron Works, for it has been used by successive owners of such works, and seems to have been used by the last partnership in no other right. In this respect the case resembles that of Motley v. Downman, 3 Myl. & Cr. 1.

“But it is unnecessary to pursue this further, for I am of opinion that these initial letters, surmounted by a crown, have become, and are, a trade-mark, properly so called—that is, a brand which has reputation and currency in the market, as a well-known sign or quality; and that as such the trade-mark is a valuable property of the partnership, as an addition to the Bloomfield Works, and may be properly sold with the works, and therefore properly included as a distinct subject of value in the valuation to the surviving partners.

“It must be recollected that the question before me is simply whether the right to use the trade-mark can be sold along with the business and iron works, so as to deprive the surviving partner of any right to use the mark in case he should set up a similar business. Nothing that I have said is intended to lead to the conclusion that the business and iron works might be put up for sale by the court in one lot, and that the right to use the trade-mark might be put up as a separate lot, and that one lot might be sold and transferred to one person, and the other lot sold and transferred to another; the case requiring only that I should decide that the exclusive right to this trade-mark belongs to the partnership as part of its property, and might be sold with the business and work and as a valuable right, and if it might be so sold, it must be included in the valuation to the surviving partner.”

It will be observed with what pains the lord chancellor guards against the conclusion that, even in such a case, the title to the trade-mark could be separated from that of the establishment upon the product of which it had always been used, even when the trade-mark was not the mere name of the place of manufacture, but a trade-mark proper, denoting the personal origin of the manufactured article.

The case of Kidd v. Johnson, 100 U. S. 617, is to the like effect. The trade-mark in that case—“S. N. Pike's Magnolia Whisky, Cincinnati, Ohio”—was a trade-mark proper; that is, indicated the personal origin of the manufacture, and was not the mere name of the place of manufacture. Pike sold his establishment to be carried on for the same business by his successors, and with it the right to use his brands. The court said, in deciding the case, (p. 620:)

“As to the right of Pike to dispose of his trade-mark in connection with the establishment where the liquor was manufactured, we do not think there can be any reasonable doubt.

“It is true, the primary object of a trade-mark is to indicate by its meaning or association the origin of the article to which it is affixed. As distinct 43 property, separate from the article created by the original producer or manufacturer, it may not be the subject of sale. But when the trade-mark is affixed to articles manufactured at a particular establishment, and acquires a special reputation in connection with the place of manufacture, and that establishment is transferred either by contract or operation of law to others, the right to the use of the trade-mark may be lawfully transferred with it.

“Its subsequent use by the person to whom the establishment is transferred, is considered as only indicating that the goods to which it is affixed are manufactured at the same place, and are of the same character as those to which the mark was attached by its original designer. Such is the purport of the language of Lord Cranworth in the case of Leather Cloth Co. v. American Leather Cloth Co., reported in 11 Jur. (N. S.) 513. See, also, Ainsworth v. Walmesley, 44 L. J. 355, and Hall v. Burrows, 10 Jur. (N. S.) 55.”

The observations of Lord Cranworth in the Leather Cloth Case, referred to in this citation, are as follows:

“But I further think that the right to a trade-mark may, in general, treating it as property, or as an accessory of property, be sold and transferred upon a sale and transfer of the manufactory of the goods on which the mark has been used to be affixed, and may be lawfully used by the purchaser. Difficulties, however, may arise where the trade-mark consists merely of the name of the manufacturer. When he dies those who succeed him (grand-children or married daughters, for instance,) though they may not bear the same name, yet ordinarily continue to use the original name as a trade-mark, and they would be protected against any infringement of the exclusive right to that mark. They would be so protected, because, according to the usages of trade, they would be understood as meaning no more by the use of their grandfather's or father's name than that they were carrying on the manufacture formerly carried on by him. Nor would the case be necessarily different if, instead of passing into other hands by devolution of law, the manufactory was sold and assigned to a purchaser.

“The question in every such case must be, whether the purchaser, in continuing the use of the original trade-mark, would, according to the ordinary usages of trade, be understood as saying more than that he was carrying on the same business as had been formerly carried on by the person whose name constituted the trade-mark. In such a case I see nothing to make it improper for the purchaser to use the old trade-mark, as the mark would, in such a case, indicate only that the goods so marked were made at the manufactory which he had purchased.”

In the foregoing cases, the trade-mark consisted either in some arbitrary and fanciful name given to the product, or in the name or initials of the original producer, and it was held, even in respect to them, that the exclusive right to continue their use might pass to a purchaser of the place of production, carrying on the business of producing the same article.

It is a fair inference from these authorities that when, as in the present case, the trade-mark consists merely in the name of the 44 establishment itself where the manufacture is carries on, and becomes attached to the manufactured article only as the product of that particular establishment, a sale of the establishment will carry with it to the purchaser the exclusive right to use the name it had previously acquired, in connection with his own manufacture at the same place of a similar article, by operation of law. For that proposition, the case of the Congress Spring, Cox's American Trade-mark Cases, 599, is a direct authority. The court of appeal, per Folger, J., (630.) said:

“The plaintiff purchased of the former proprietors the spring. They took the whole property in it. They thus obtained that which was the prime value of it, the exclusive right to preserve its waters in bottles, as an article of merchandise, and the exclusive right to sell it when bottled. Thus they acquired the business of their predecessors, for the plaintiff, owning the spring, no one else could carry on the business. And, under the rules above stated, they acquired by assignment, or operation of law, the right to the trade-mark, before that time in use, to designate the article upon which this business was carried on.”

It is true, as observed by counsel in argument, that in that case the article of merchandise was a natural, and not, as in the present, an artificial, production. That circumstance was observed upon, in the argument of that case, as a reason for refusing the protection claimed for the trade-mark by the purchaser. The court said in reply, (p. 625:)

“It is true that, in most of the cases which have been the occasion of the rules laid down on this subject, the article in question has been artificial. But it will be difficult to show a reason for any of these rules which does not apply to the proprietorship of an unique product of nature, as well as to that of an unique product of art.”

The following cases are cited without comment as sustaining the same proposition: G. & H. Manuf'g Co. v. Hall, 61 N. Y. 229; Carmichael v. Lattimer, 11 R. I. 407; and Booth v. Jarrett, 52 How. Pr. 169.

The cases cited and relied upon by counsel for complainant do not seem to us to affect the question in the view which we have taken of the facts. The only one upon which we think it important to submit a comment is that of Wotherspoon v. Curric, L. R. 5 Eng. & Ir. Ap. 521, and that, only because it seems to be urged as inconsistent with the view we have been compelled to adopt. In that case the controversy turned upon the exclusive right to the word “Glenfield,” as applied to starch originally made at a village of that name, the manufacture of which was subsequently removed to another 45 place, as against the defendant subsequently manufacturing at the original place—Glenfield—and claiming on that account the right to use the name in connection with the starch made by him. Lord Westbury stated the point on which the final decision in favor of the complainant was rested, with clearness. He said:

“I take it to be clear from the evidence that long antecedently to the operations of the respondent the word “Glenfield” had acquired a secondary signification or meaning in connection with a particular manufacture; in short, it had become the trade denomination of the starch made by the appellant. It was wholly taken out of its ordinary meaning, and in connection with starch had acquired that peculiar secondary signification to which I have referred. The word ‘Glenfield,’ therefore, as a denomination of starch, had become the property of the appellants. It was their right and title in connection with the starch.”

We do not find in the present case any state of facts corresponding with this. The words “Old Oscar Pepper Distillery” never lost their primary signification, and never acquired any secondary meaning; and, as applied to the whisky made by the complainant, the words “Old Oscar Pepper,” and their abbreviation, “O. O. P.,” never came to mean more than whisky that had been made at that particular distillery. They did not become a denomination of whisky as the manufacture of the complainant or of any person, but characterized it only as entitled to public favor by reason of the reputation of the particular distillery at which it purported to have been made.

For these reasons we are of opinion that the equity of the case, both upon the original and cross-bills, is with the defendants. A decree may be entered accordingly.

BARR, D. J., concurred.

* Reported by J. C. Harper, Esq., of the Cineinnati bar.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Tim Stanley.