1123

P.

Case No. 18,311.

30FED.CAS.—72

30FED.CAS.—73

Case of PEA PATCH ISLAND.

[1 “Wall. Jr. Append. ix.]1

Arbitration at Philadelphia.

Jan. 15, 1848.

BOUNDARIES—DELAWARE AND NEW JERSEY.

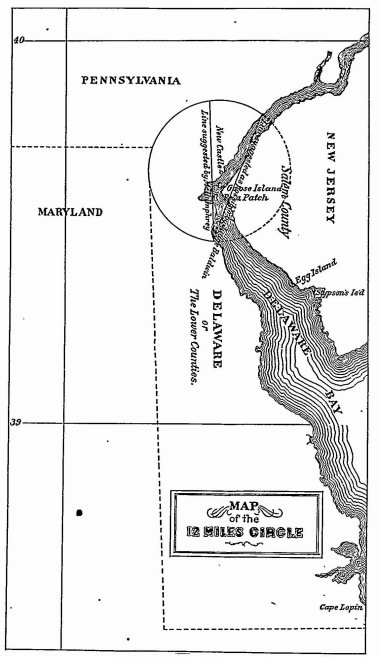

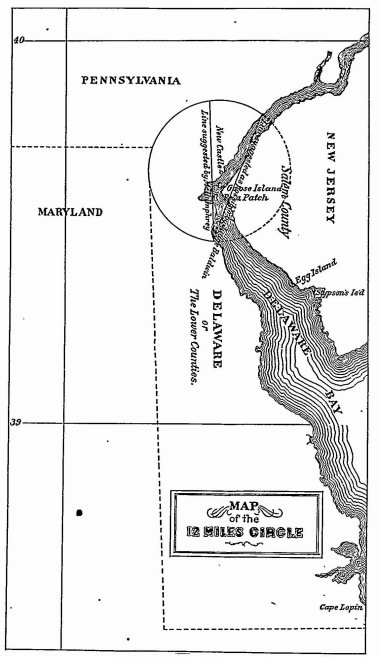

The territory of the state of Delaware within the twelve miles circle” extends across the Delaware river to low water mark on the Jersey shore.

About the year 1783-84, there appeared at low tide in the Delaware river, about five miles below New Castle, a small muddy exposure of the soil, “about the size,” as was testified, “of a man's hat.” By the force of alluvion and deposit the exposure became larger and larger, until, by degrees, it formed an island of about 87 acres, which in consequence of a tradition that a vessel laden with peas had once sunk on the spot where the island afterwards rose, got the name of the “Pea Patch Island.” In 1784, the proprietaries of West Jersey granted this island, describing it as situate in Salem county, New Jersey, to persons whose title became afterwards vested in Dr. Henry Gale of that state; and in 1831, the same state, by an act of its legislature, relinquished to Dr. Gale whatever interest it might have in the island. It had previously declared that its west boundary, at this place, came to the middle of the main channel of the Delaware river, a location which, as the main channel was then supposed to run, included the Pea Patch Island as within the territory of New Jersey. In 1813, the state of Delaware, by an act of its legislature, conveyed the island to the United States, who soon after took possession of it and began to erect a fortress upon it. In consequence of these two grants, a controversy as to the right to the island began between Dr. Gale, claiming under the title of New Jersey, and the United States claiming under that of Delaware. In the ordinary case of a dispute as to title between an individual and the government, the matter would not have attracted publick notice; but this case differed in several respects from an ordinary case. In the first place, it brought in question the boundary between the states of New Jersey and Delaware; and to common apprehension it brought, moreover, some disparagement to one state or the other, both of which had apparently treated the island as within its own limits; and both of which, it was asserted, had granted it away, as its own property. Publick attention was moreover directed to the matter from the accidental position of the island itself. Above it lie many principal towns or cities, of the three states of Delaware, Pennsylvania and New Jersey, which could he readily devastated by an enemy's fleet unless the river was protected from below; while it so happens, from the width, the course, or the shifting character of the Delaware channel, that there is scarcely any point either above or below, that offers a place where adequate defences could be erected for any of them. This island, however, constitutes the key of defence of the whole river. It stands just in the centre of its entrance and commands its two channels, of which the deepest runs close along its side, and the other is so curved as to lie for a great distance directly and most favourably exposed to its guns. A fortress had been partially erected on the island by the United States during the war of 1812, but was destroyed by fire some years after. And all the towns along the Delaware river, lying, as already stated, naked to attack from any enemy who might pass up it, were kept in great uneasiness during those many years in which the “Maine Boundary,” the “French Indemnity,” the “McCleod Arrest” and the “Oregon Boundary” had kept our relations with the two great naval powers of Prance and England in uncertainty, and put them, at times, in danger of immediate rupture. Of course, they were constantly imploring congress to complete or rebuild the fortress upon this island, the only place, as all agreed, where an adequate defence could be erected; while at the same time the New Jersey claimants would appear with assertions of title to the island, fortified by written opinions from the law officers of the government itself,2and by remonstrances from citizens of New Jersey against such an unlawful invasion of their territory as was contemplated by assuming possession of the island, except under grant of the individual proprietor. In addition to this, the matter had attracted attention from a great number of unsuccessful attempts—necessarily publick ones—by the departments and by congress to settle it; from an uncommon number of opinions of directly opposite conclusion, from lawyers of publick name, both those connected with the government and those in private station; and finally from two judgments in two different circuits of the United States, which were in like conflict, and under which, in a suit between the same parties, the harmonious operation of the federal courts was made the witness of a marshal of one district turning out of possession the tenants who had lately been put in by the marshal of another! It would unnecessarily incumber this preliminary history of the case to record the various presidential recommendations, the reports of committees, the opinions of district attorneys, solicitors of the treasury and attorneys general of the United States, the congressional debates, and the various abortive agreements entered into by the departments with a view to settle the question. It would be the history of litigation and claim diligently pursued for three and thirty years; and which at last, by opinions and agreements, verdicts and legislation, had knotted and tied itself into such a complication of tangles, that it seemed past the possibility of any ordinary process of justice ever to unfold and draw it straight And when it was remembered that opinions of directly opposite conclusion on the title, had been given by Messrs. Rodney and Geo. Bead of Delaware, by Messrs. Richard Stockton, McILvaine, Southard, G. D. Wall and J. S. Green of New Jersey, by Mr. Willis Hall of New York, by Messrs. Penrose and Gilpin, solicitors of the treasury, and finally by Messrs. B. P. Butler and Legare, attorneys general of the United States, it was not wonderful that both congress and claimant should nearly give over in despair, all hopes of coming to any satisfactory conclusion; that the petitioner should have been weary of invoking the attention of congress, and that congress should have been impatient in listening to the prayers of the petitioner!

In this state of long protracted litigation and treaty, on the 8th of August, 1846, when the Oregon boundary had lately been giving to our relations with Great Britain a menacing 1124aspect, congress passed an act [9 Stat. 67], authorizing the president of the United States “to take such steps as he may deem advisable for adjusting the title to the Pea Patch Island.” In pursuance of this authority, communications were had between the president, in behalf of the United States, and the Hon. John H. Eaton, counsel of the New Jersey claimant, by which it was agreed to submit the question of the title to the arbitration of some professional gentleman, in whose ability, learning and honour both parties should have such implicit confidence, as to be willing to accept, as final and conclusive, whatever award he might make upon the question. Mr. Eaton having nominated to the president four gentlemen of this character from the District of Columbia, the states of Maryland, Pennsylvania, and New York, President Polk made choice of the Honourable John Sergeant of Pennsylvania, one of the persons named; a selection which was at once responded to by the other side as eminently acceptable. Accordingly on the 27th February, 1847, articles of agreement under seal were concluded between the Hon. W. L. Marcy, secretary of war of the United States, acting with the approbation of the president of the United States, of the one part, and James Humphrey, in whom Dr. Gale's title had become vested, of the other, by which they mutually appointed John Sergeant, Esquire, of Philadelphia sole arbitrator, with full power and authority, at such times and places as he might appoint, to examine witnesses and receive evidence according to the rules of law and equity, and to decide the question of the title to the said Pea Patch Island, as derived by the United States from the state of Delaware and by the said James Humphrey, claiming through Henry Gale, deceased, from the state of New Jersey. His decision and award made in writing to be final and conclusive.

The matter being one to which publick attention in Eastern Pennsylvania, in New Jersey and Delaware had long been directed, Mr. Sergeant readily complied with the wish, very generally existing, that the case should be heard publickly; and the county of Philadelphia having offered to the arbitrator its principal judicial chamber, and the city of Philadelphia having likewise placed at his disposal the hall in which Independence was declared, the case,” which occupied twenty-one days in the trial, was heard partly in the former room and partly in the latter, to which it was found convenient after a certain time to adjourn. The United States, were represented by special counsel, to wit, the Honourable John M. Clayton of Delaware, formerly chief justice of that state, and now its representative in the senate of the United States, and by James A. Bayard, Esq., of the same state, formerly district attorney of Delaware, for the United States. Mr. James Humphrey was represented by the Honourable George M. Bibb of Kentucky, successively a judge, chief justice and chancellor of that state, also, at one time, its representative in the senate of the United States, and more lately the secretary of the treasury of the United States under President Tyler: and by the Honourable John H. Eaton, of Tennessee, secretary at war under President Jackson, and subsequently minister plenipotentiary of the United States at the court of Spain. The case was learnedly and deliberately argued on both sides; and Mr. Sergeant, after taking several weeks consideration of it having delivered a written opinion setting forth very fully the grounds of his award, it has been thought worth while thus to preserve some record of the proceeding. Of the value of the opinion, the reporter cannot speak more appropriately than in language which he finds in a contemporaneous publication: “Mr. Sergeant's opinion it is true,” said one of the journals of Philadelphia (the North American and United States Gazette of January 17, 1848), in speaking of its delivery, “is not the judgment of a supreme court, and therefore is not authority in the technical sense of that word; but as the well reasoned opinion of a very able lawyer—whose greater distinction in his profession has made him unsolicitous about judicial station—and as having been formed after full and grave publick argument before him for many days together by other very able lawyers, it is far more authoritative than any opinion merely professional, and has all the intrinsick weight of the highest judicial opinion. It can scarcely be reversed in any case which may again involve the question of this boundary, and will take its place, of course, among the most enduring historical monuments of the states of New Jersey and Delaware.

The case as it appeared on both sides was as follows:

Title of Mr. Humphrey: On the 12th March, 1663-64, England being at that time at war with the Dutch, Charles II. by letters patent, granted in fee to his brother James, Duke of York, all that part of the main land of New England, beginning at St. Croix next adjoining New Scotland in America, &c. &c, and also all that island called Matowacks or Long Island, situate to the west of Cape Cod and the narrow higansetts, abutting upon the main land between the two-rivers called Connecticut and Hudson rivers, “together also with the said river called Hudson's river, and all the lands from the west side of the Connecticut to the east side of Delaware Bay,” with certain islands, and with all the lands, islands, soils, rivers, harbours, mines, minerals, quarries, woods, marshes, waters, lakes, fishings, &c, and all other royalities, profits, commodities and hereditaments to the said islands, lands and premises belonging and appertaining, with their and every of their appurtenances, and all our estate, &c, of, in and to the said lands and premises or any part or parcel thereof, with powers of government in extenso, and to exercise them, “not only within the precincts of the said territories and islands, but also upon the seas in going and coming to and from the same,” as the duke and his assigns, &c, should think “for the good of the adventurers and inhabitants there:” with further power to admit any persons “to trade and traffique unto and within the said territories and islands,” and to encounter, expulse, repel and resist by force of arms, “as well by sea as by land, all persons who without the duke's leave, “should attempt to inhabit within the several precincts and limits of our said territories and islands.” Learning & S. Laws N. J. 3-8.

The object of this grant was to enable the duke to dispossess the Dutch, who were then in possession of much of New York, New Jersey and Delaware, under the name of New Netherlands.

The Duke of York on the 23d and 24th June, 1664, reciting the king's grant to him, conveyed to Lord Berkeley and Sir Geo. Carteret the territory now known as New Jersey, describing it as bounded on the east, part by the main sea, and part by Hudson's river, “and hath upon the west, Delaware bay or river:” with all rivers, fishing, &c. and all other royalties, &c. to the said lands and premises belonging or in any wise appertaining, as fully as the duke himself had them. Learning & S. Laws N. J. 8-11.

The object of this deed was the colonization of New Jersey, and under it Berkeley and Carteret entered and colonized that state accordingly.

It is unnecessary here to recite the various mesne conveyances and undisputed early historical facts through which Mr. Humphrey formally deduced his title; or to state more than 1125that on the 7th November, 1743, the proprietors of West Jersey-in which portion of the state the Pea Patch Island was admitted to be, if in any-directed their surveyor to survey, co., “600 acres of unappropriated land,” any where in that division, and on the 7th August, 1782, to survey 5000 acres of like land, I the same division: and that two persons named Hall, having acquired 126 acres of the warrant  of 1782, and

of 1782, and  acres of that of 1743, caused a survey to be made on the 8th October, 1784, on an “island” as appeared by the return of survey, “called the Pea Patch, situate in the county of Salem, about one mile west from Finn's Point, in Penn's Neck, and is about west of the mouth of Salem creek, a little above Reedy Point; also nearly southeast and by east from Hamburgh, about two and a half miles and about south half a point west from the Tile house at New Castle; containing one hundred and seventy-eight acres of marsh land, bank and mud flats and allowance for roads.” This survey was returned on the 27th of the same month, and being approved by the council of proprietors, was recorded accordingly. At the date of this survey the Pea Patch was just visible at low water, “about the size of a man's hat.” As the tide rose it was covered by water, and even in 1815, when the government of the United States took possession of it and embanked it, it was not unfrequently under water at high tide. In February, 1813, the title of the Halls was vested in Dr. Gale, through whom Mr. Humphrey claimed by a regular chain. On the 24th November, 1831. the Pea Patch, having become, in the 1126meantime, by alluvion, deposit and embankment, a large island, and entirely above the point to which the tide rises even in its highest elevation, the state of New Jersey passed an act of assembly, “vesting in Henry Gale, his heirs and assigns, all the right and title of the state of New Jersey of, in and to an island called the Pea Patch, situate in the river Delaware, in the county of Salem, and state of New Jersey.” The act after reciting that “it hath been suggested that the state of New Jersey hath some title” to the island, and that by reason thereof doubts have arisen concerning the title of the said Henry Gale, enacts that “all the right and title of the said state of New Jersey to the said island called the Pea Patch, situate in the river Delaware, in the township of Lower Penn's Neck, in the county of Salem, in the state of New Jersey,” &c, as mentioned in the original survey of the island, be granted and conveyed to the said H. G., his heirs and assigns, and be vested in him and them “in as full and ample a manner as the state of New Jersey hath right and title to grant and convey the same,” reserving jurisdiction and sovereignty, &c. 2 Harrison's Laws N. J. 366.

acres of that of 1743, caused a survey to be made on the 8th October, 1784, on an “island” as appeared by the return of survey, “called the Pea Patch, situate in the county of Salem, about one mile west from Finn's Point, in Penn's Neck, and is about west of the mouth of Salem creek, a little above Reedy Point; also nearly southeast and by east from Hamburgh, about two and a half miles and about south half a point west from the Tile house at New Castle; containing one hundred and seventy-eight acres of marsh land, bank and mud flats and allowance for roads.” This survey was returned on the 27th of the same month, and being approved by the council of proprietors, was recorded accordingly. At the date of this survey the Pea Patch was just visible at low water, “about the size of a man's hat.” As the tide rose it was covered by water, and even in 1815, when the government of the United States took possession of it and embanked it, it was not unfrequently under water at high tide. In February, 1813, the title of the Halls was vested in Dr. Gale, through whom Mr. Humphrey claimed by a regular chain. On the 24th November, 1831. the Pea Patch, having become, in the 1126meantime, by alluvion, deposit and embankment, a large island, and entirely above the point to which the tide rises even in its highest elevation, the state of New Jersey passed an act of assembly, “vesting in Henry Gale, his heirs and assigns, all the right and title of the state of New Jersey of, in and to an island called the Pea Patch, situate in the river Delaware, in the county of Salem, and state of New Jersey.” The act after reciting that “it hath been suggested that the state of New Jersey hath some title” to the island, and that by reason thereof doubts have arisen concerning the title of the said Henry Gale, enacts that “all the right and title of the said state of New Jersey to the said island called the Pea Patch, situate in the river Delaware, in the township of Lower Penn's Neck, in the county of Salem, in the state of New Jersey,” &c, as mentioned in the original survey of the island, be granted and conveyed to the said H. G., his heirs and assigns, and be vested in him and them “in as full and ample a manner as the state of New Jersey hath right and title to grant and convey the same,” reserving jurisdiction and sovereignty, &c. 2 Harrison's Laws N. J. 366.

In order to show that the deeds from the king and duke had always been considered and acted upon from early times as not limiting the state of New Jersey to low water mark in the Delaware bay and river, or at any rate that the state had never been so bounded de facto, Mr. Humphrey's counsel adduced several statutes and publick facts and records of that state, as follows:

March 3, 1676, the proprietaries of West New Jersey—William Penn himself being one of them—by certain articles of concession and agreement, which constituted a sort of charter or fundamental law, grant convenient portions of lands for wharves, keys and harbours: and that all lands laid out for the said purposes shall be exempt from taxes; and that the inhabitants of the province have free passage through or by any seas, bounds, creeks, rivers, rivulets in the said province, through or by which they must necessarily pass to come from the main ocean to any part of the province aforesaid. And, further, that all the inhabitants within the said province have liberty of fishing in Delaware river. Learning & S. Laws N. J. 390; also, to the same effect, Id. 409.

In 1679 and 1680, Sir Edmund Andros, the governour for the Duke of York, of the colony of New York, which had been conveyed (inter alia with New Jersey) to the duke, by King Charles II. imposed a duty of ten per cent, upon all European goods imported into the Delaware, which was collected at the Hoar Kills, or Lewistown, as it is now called. But it was discontinued at the instance of the proprietors of New Jersey, who, in their remonstrance, insist that they have a right to land any where in the Delaware Bay, as the bounds of the country they bought; that the right of colonizing was part of their bargain; that they bought the soil and right of government together; and that the powers of government limited them to erect no polity contrary to the laws of England; and that, with this restriction, they had the right of making laws for the good of the adventurer and planter; that if the duke claims it by the jus regale, that power over the territory constituting New Jersey is vested in his alienees. Smith, Hist. N. J. 116.

In 1682, the legislature of New Jersey resolved that the land and government of West New Jersey were purchased together. Smith, Hist. N. J. 163.

On the 3d October, 1693, the assembly of West New Jersey passed an act reciting that the whalery in Delaware Bay has been in so great a measure invaded by strangers and foreigners, that the greatest part of the oil, &c, got by that employ, has been exported out of the province, &c; and enacting that all persons not residing within the precincts of this province, or within the province of Pennsylvania, who shall kill or bring on shore any whale or whales “within Delaware Bay or elsewhere within the boundaries of this government,” shall pay one-tenth of the oil, &c. to the governour, &c. Learning & S. Laws N. J. 519.

In 1701 or 1702, the proprietors of East New Jersey, treating with the lords of the council of trade and foreign plantations about a surrender to the crown, of the powers of government of the state, which was then contemplated, request the king to confirm to them certain rights and privileges, among which is that of having all “wrecks and royal fish that shall be forfeited, found or taken within East New Jersey or by the inhabitants thereof, within the seas adjacent” (Learning & S. Laws N. J. 588, 590, 591), as they had the same under a then existing grant. Though the answer of the commissioners does not give them a fully satisfactory answer, it does not deny that these rights and privileges were then lawfully enjoyed by the proprietors (Id. 596).

On the 23d August, 1725, the legislature of New Jersey passed a revenue act, laying taxes upon eight different ferries along the Delaware river, from Trenton to Gloucester across to the other shore: and for the effectual compelling of the said boats, flats or wherries belonging to the neighbouring colonies to pay such taxes as aforesaid, it enacts that “all boats, flats or wherries, that carry goods or passengers for hire as aforesaid, that shall not first pay unto the collector of his majesty's customs, &c. and get a certificate that he has paid the tax aforesaid, shall forfeit for every offence,” &c. Wm. Bradford's Laws N. J. 1717, pp. 129, 130.

In 1765, the legislature of New Jersey passed “An act to regulate the method of taking fish in the river Delaware, and to prevent obstructions in the navigation thereof, and for other purposes therein mentioned.” This act, which was limited to five years, and was to he dependent for its force upon the passage of a similar act by Pennsylvania, was revived conditionally, with a supplement to it passed in 1768, in the year 1771. Allinson's Laws N. J. 279, 313, 367. Pennsylvania did not pass any similar act, and the act of New Jersey not having become operative, nothing beyond its title is given in the volume referred to.

On the 21st December, 1771, the same legislature passed “An act declaring the river Delaware a common highway, and for improving the navigation in the said river.” Allinson's Laws N. J. 347. It recites that the improving the navigation on rivers is of great importance to trade and commerce; that the river Delaware may be rendered much more navigable than it now is; that many persons, desirous to promote the publick welfare had subscribed large sums of money for the purpose aforesaid, and that it was represented others will do the same if commissioners are appointed to receive subscriptions. It then enacts “that the river Delaware shall be and it hereby is declared to be a common highway for the purposes of navigation up and down the same.” It then appoints commissioners to collect subscriptions, and “so much of the said moneys as may be necessary for that purpose, to lay out and apply for, and towards improving the navigation in the said river Delaware, from the lower part of the falls near Trenton, to the river Lehigh at Easton: and the residue thereof to lay out and apply for and towards improving the navigation in that part of the said river, above the said river Lehigh.” It next enacts (section 3) that the commissioners, &c, shall have “full power and authority to clear, scour, open, enlarge, straighten, or deepen the said river, wherever it shall to them appear useful for improving the channels; and also to remove any obstructions whatsoever, either natural or artificial, which may or can in any manner hinder or impede 1127the navigation in the said river' and to make and set up in the said river any dams, pens for water-locks, or any other works whatsoever, and the same to alter and repair as they shall think fit: and also to appoint, set out and make near the said river, paths or ways, which shall be free and open for all persons having occasion to use the same for towing, hauling or drawing any vessels, boats, small craft and rafts of any kind whatsoever; and from time to time to do and execute every other matter or thing necessary or convenient for improving the navigation in the said river.” It afterwards (section 5) “makes it penal to hinder the commissioners or to obstruct the navigation of the river:” and, by section 6, that “every offence committed in or on the said river, against this act, shall be laid to be committed, and may be tried and determined as aforesaid in any of the counties opposite to or joining on that part of the said river, on which such offence shall be committed.”

On the 28th November, 1822 the legislature of New Jersey passed an act relative to certain of its boundaries, in which it was enacted that the west boundary of certain counties, including Salem county, in which the Pea Patch was said to be, should be “the main ship channel of the river Delaware.” 2 Harrison's Laws N. J. 39, § 4.

On the other hand, there were certain publick acts of New Jersey which looked as if the state had considered that its west boundary came but to low water mark in the river.

Thus, in 1674 and in 1680, New Jersey having been conquered by the Dutch since the deeds of the Duke of York, 23d and 24th June, 1664, and restored again to England—the duke, by two new deeds, made after a regrant by the crown to him, and with a view, it is probable, to prevent any question of title, regrants the same territory previously granted, describing it on its west boundary, not as in the former deed, as “having on the west, Delaware river,” but in one deed, as extending “along,” and, in another, as running “up” the Delaware. Learning & S. Laws N. J. 47, 414.

So in February, 1681, the commissioners for settling and regulating lands in “West Jersey agree, with the approbation of the governour and council, that the surveyor shall measure the front of the river Delaware, beginning at Assispink creek, (a creek which empties into the Delaware at Trenton,) and “from thence down to Cape May,” and that every ten proprietors shall have their proportion of front “to the river.” Learning & S. Laws N. J. 436.

So in July, 1683, the assembly of West Jersey enact that the proprietary of the province of Pennsylvania be treated with in reference to the rights and privileges of this province “to or in the river Delaware.” Learning & S. Laws N. J. 480.

So on the 21st January, 1709, the general assembly of New Jersey passed “An act for dividing “and ascertaining the boundaries of all the counties in this province;” which recites that by the uncertainty of the boundaries of the counties of the province, great inconveniences have arisen, so that the respective officers of most of those counties cannot know the limits of them: For preventing which in time to come, and the better ascertaining the boundaries, it enacts, &c. (after having settled the boundaries of other counties as running “to” or “by” or “up” or “down” the Delaware bay or river,) that Salem county begins “at the mouth” of a certain creek which empties into Delaware Bay. The act then carries the boundary round by that creek and certain lines “to Delaware river, then down Delaware river and bay to the place of beginning.”3It is to be remarked, however, that where counties are divided by creeks or rivers, this act frequently brings the boundaries of such counties only to those creeks or rivers on both sides, without extending the boundary into the stream; so that many of those creeks and rivers were left beyond any county jurisdiction whatever, until that matter was changed by an act of March 7, 1797, “declaring the jurisdiction of the several counties in this state, which are divided by rivers, creeks, bays, highways or roads.” Id. 180.

On the 26th April, 1783, commissioners having been appointed by Pennsylvania, for the purpose of settling the jurisdiction of the river Delaware and islands within the same, New Jersey made an agreement regulating the jurisdiction, &c, and treating the rights of the two states in the river as about equal, down to the upper portion of the twelve miles circle; which agreement was soon after ratified (by New Jersey, May 27, 1783; by Pennsylvania, September 20, 1783, Id. 41) by these two states and has regulated the matter ever since.

Title of the United States: At the date of the letters patent of March 12, 1663-64, already mentioned, from Charles II. to the Duke of York; the Dutch were in actual possession of New York, a-portion of New Jersey and much of both sides, and particularly of the west side of Delaware bay and river; all which they held under the name of New Netherlands. To put the Duke of York in possession of his newly acquired estates, an English fleet was sent out under the command of Col. Richard Nicolls, who styles himself “principal commissioner for his majesty in New England, governour general under his royal highness, James Duke of York and Albany, &c, of all his territories in America and commander in chief of all the forces employed by his majesty to reduce the Dutch nation and all their usurped lands and plantations under his majesty's obedience.”4The Dutch surrendered New York, August, 1664, and within a week afterwards Col. Nicolls sent Sir Robert Carre round into Delaware bay and river, to dispossess the Dutch there. 1 Hazzard, Pa. Reg. 37. This Dutch settlement appears to have been an appendage to the government of New York, or Manhattans, as it was then called, from which it originally sprung, and to which, as a superintending and protecting power, it appears to have constantly referred. Thus the original Dutch purchase of Delaware from the Indians in June, 1620, was concluded by the Indians in person at New York, and recorded there. 4 Hazzard, Pa. Reg. 82. So when the Swedes began to build a fort on the Delaware, about the year 1638, the director general of the New Netherlands, resident at New York, and appointed by the states general, advertises the Swedish commander, that the “whole South river has been many years in our possession, and above and below settled by our forts and also sealed by our blood.” Id. So in 1646, the director general, allowed certain persons to settle upon the South river, on condition that they acknowledge the director and his council “for their lords and patrons,” and submit to all taxes which they have laid or may lay. Id. 119. And there was produced before the arbitrator, ancient records of five Dutch patents for lands in Delaware, emanating from Governour Stuyvesant at New York, between the years 1664 and 1665, and recorded there (Id. 119, 120), which titles, Mr. Clayton informed the arbitrator, are recognized as valid in Delaware up to this day. Other Dutch records from New York showed that in 1665 instructions were issued from the director general there, “for the vice director in the South. 1128river and the commissioners joined with them,” in which minute directions are given as to the places in which lands are to be granted and streets laid out there (Id. 82), with various other instructions shewing that that district had a very close and depending relation upon the government at New York as a principal.

In this condition of things, the Delaware country apparently stood in regard to the Dutch government at New York, when the latter surrendered to the English: And with the surrender of the principal government at New York, Sir Robert Carre had no difficulty, on the 1st October, 1664, in procuring a surrender of the settlement on the Delaware.

New York continued to be, under the English, as it had been under the Dutch, the seat of principal government; the English governours there, acting under a sort of double or mixed authority derived partly from the king and partly from the Duke of York. A variety of commissions and other publick documents, for example, were produced from Col. Nicolls, and other English governours there, granting lands in Delaware, constituting justices there, appointing collectors of customs, and doing various publick acts not necessary to be stated. In eight of them, including several grants of land,5there was no recital of the authority under which the act professed to he done. In ten others, being most of them commissions to judicial office, there was a reference to “his majesty's service,” or to power derived from “his majesty;” the act being sometimes done in “his majesty's name.” In eleven others—including a grant of land, of which however the rent was reserved to the king—the power under which the act was done professed to be derived from the Duke of York. Two others recited a joint or double authority; being “by virtue of his majesty's letters patent, and the commission and authority given unto me by his royal highness.” And a third one, a proclamation by Governour Andros, one of the British governours—on the re-conquest of New York from the Dutch—went as follows: “Whereas, it hath pleased his majesty and his royal highness, to send me with authority to receive this place and government, and to continue in command thereof under his royal highness, who hath given me his command for securing the rights and properties of the inhabitants, and that I should endeavour by all fitting means the good and welfare of this province and dependencies under his government, &c.” 4 Hazzard, Pa. Reg. 55-57, 73-75, 81, 82. So again, when the Delaware country surrendered to Sir Robert Carre, Oct. 1, 1664, protection was to be afforded to all who “shall take the oath of allegiance to his majesty:” While in directions from Gov. Nicolls and his council at New York, in 1668, “for the better settlement of the government on the Delaware,” the newly appointed counsellors are to take the oaths to his royal highness; whose laws as established by him, are ordered to be shewed and frequently communicated to them, the said counsellors, and others.” Id. 37, 38. A fact is also mentioned by the arbitrator in his opinion, as illustrative of some title in the duke, to wit, that after Mr. Penn, March 4, 1680-81, had obtained letters patent from Charles II. for the province of Pennsylvania, he took a release, August 21, 1682, from the Duke of York for the same premises.

But notwithstanding the great research of the counsel of the United States, aided by several other persons connected with historical societies and curious in archæology—whom the interest of the case had induced to study it—nothing precise was shewn as to the source from which the duke claimed to derive the power which it was in evidence that he actually exercised over the district now known as Delaware. Whether that duke was under the same mistake as Lord Baltimore, who, as late as 1737, in his answer to the bill of Penns v. Baltimore, swears that country is “on the east side” of the bay; which would have brought it strictly within the terms of the king's patent of March 12, 1663-4: Whether—taken in connection with the known object of the grant, which was the dispossession of the Dutch from all this region—he supposed that it passed under the clause of the patent, which gave him power to encounter and expulse, as well by sea as by land, any persons who should attempt to “inhabit within the several precincts and limits” of the territories granted with full appurtenances and with power to govern them: Whether he thought that the Dutch settlement on the Delaware, having been at all times, and at the very date of the conquest of New York, a part, “appendix,” and dependency of that latter place, necessarily followed its course and fortune, and so passed into his hands by the terms of his patent, which gave him New York, and all powers of government over the country conveyed and all its appurtenances: Whether there might have been something, in some commission, or some instructions from the king to the English commander, which two centuries now rose up to hide from view, and by which a title by conquest might have enured to the duke and not to the crown: Whether the duke considered that he had no title in law, and took possession only as a successful conqueror, meaning to procure or make at some future time, a confirmation of what he did: Or whether, finally, he exercised the more usual privilege of royal and noble blood, and did not undergo the fatigue of thinking any thing about the subject: This was all matter on which speculation might exercise its ingenuity, but on which the case itself exhibited no direct evidence.6

However, possessing either a good title, an imperfect one, or no title at all, the Duke of York did, on the 24th of August, 1682, by a deed of feoffment with livery of seizin, convey to William Penn, in fee, “all that the town of New Castle, otherwise called Delaware, and all that tract of land lying within the compass or circle of twelve miles about the same, situate, lying and being upon the river Delaware, in America; and all the islands in the said river Delaware, and the said river and soil thereof, 1129lying north of the southernmost part of the said circle of twelve miles about the said town, together with all rents, services, royalties, franchises, duties, jurisdictions,” &c. &c. and all the estates, &c. “to have and to hold the said town and circle of twelve miles of land about the same, islands, and all other the before mentioned,” &c. &c. The duke for himself, his heirs and assigns, then covenants and grants with and to Penn, his heirs and assigns, that lie or they will, any time within seven years from the date of the deed, “do, make, execute or cause to be made, done, executed, all and every such further act and acts, conveyances and assurances in the law whatsoever, for the further conveying and assuring the said town and circle of twelve miles of land about the same, and islands and all other the premises with the appurtenances” to Penn in-fee: after which he constitutes John Moll and Ephraim Herman, “jointly and either of them severally,” his attorneys, and so gives them full powers for him and in his name and stead to enter into the premises granted, and every part of them, and to take quiet and peaceable possession or seizin of them, or any part or parcel in the name of the whole: And after taking such quiet and peaceable possession and seizin, to deliver the same to William Penn, his heirs and assigns, or to his and their lawful attorney. Ratifying, approving, &c.7

The duke, on the same day, by a second deed of feoffment with livery of seizin, conveyed to William Penn, in fee, “all that tract of land upon Delaware river and bay, beginning twelve miles south from the town of New Castle, otherwise called Delaware, and extending south to the Hoar Kills, otherwise called Cape Henlopen, together with free and undisturbed use and passage into and out of all harbours, bays, waters, rivers, isles and inlets, belonging to or leading to the same; together with the soil, fields, woods, underwoods, mountains, hills, fens, isles, lakes, rivers, rivulets, bays and inlets situate in, or belonging unto the limits and bounds aforesaid, together with all sorts of minerals, and all the estate, interest, royalties, franchises, powers, privileges and immunities whatsoever of his said royal highness therein or in or unto any part or parcel thereof.” Then there was a covenant for further assurance, and an appointment of Moll and Herman to be attorneys to deliver possession and seizin to Penn exactly as in the former deed.

It further appeared from an ancient record In the rolls office at Philadelphia, made 28th August, 1701, that on the 28th of October, 1682, as they certify under their hands and seals, Arnoldus de La Grange and eleven other persons, “being inhabitants of the town of New Castle upon Delaware river, having heard the indenture read, made between his royal highness, James Duke of York and Albany, &c, and William Penn, Esq., governour and proprietor of the province of Pennsylvania, &c, wherein the said duke transferreth his right and title to New Castle and twelve miles circle about the same, with all powers and jurisdictions and services thereunto belonging unto the said William Penn, and having seen by the said duke's appointed attorneys, John Moll and Ephraim Herman, both of New Castle.' possession given, and by our Governour William Penn, Esq., possession taken, whereby we,” says the record, “are made subjects under the king to the said William Penn, Esq.: We do hereby, in the presence of God, solemnly promise to yield him all just obedience, and to live quietly and peaceably under his government.”

It appeared further from an ancient record, made at the same time, in the same office, that the same Arnoldus de La Grange and eight other persons made a memorandum under their hands, October 28, 1682, that on that day and year “William Penn, Esq., by virtue of an instrument of indenture, signed and sealed by his royal highness, James Duke of York, &c, did then and there demand possession and seizin of John Moll, Esq., and Ephraim Herman, gentlemen (attorneys constituted by his said royal highness), of the town of New Castle, otherwise called Delaware, with twelve miles circle or compass of the said town: that the possession and seizin was accordingly given by the said attorneys to the said William Penn, according to the usual form, by delivery of the fort of the said town, and leaving the said William Penn in quiet and peaceable possession thereof, and also by the delivery of turf and twig, and water and fowl of the river Delaware, and that the said William Penn remained in the peaceable possession of the premises.”

Next an ancient record, made at the same time and place, the original of which was made in Delaware river, under the hands of Luke Wattson and ten other persons, November 7, 1682, which, after reciting the duke's deed to William Penn for the territory beginning twelve miles south from the town of New Castle, the power of attorney to Moll and Herman, and that Mr. Penn had substituted Captain William Markham, as attorney to receive seizin for him of that said tract, proceeds to testify and declare that livery of seizin was delivered of it also; that the persons whose names are subscribed to the document, on the day of the date thereof, “have been present and seen, that they the said John Moll and Ephraim Herman, in pursuance of his royal highness' command, and by virtue of the power given them by his said royal highness. James Duke of York and Albany, etc., by and in the above mentioned instrument of indenture, bearing date as above, have given and delivered actual possession unto the said Captain William Markham, to the sole use and behoof of the said William Penn, (of part in the name of the whole,) of the land, soil and premises in the said instrument of indenture mentioned, and according to the true intent and meaning of his said royal highness mentioned in the same.”

Next came another ancient record, without date, however, from the office for recording of deeds, &c, at New Castle, Delaware; being an account by John Moll, himself, one of the persons named in the duke's deeds as attorneys for delivering seizin of both tracts to Mr. Penn, of the mode in which he did this duty. As this quaint document has not perhaps been in print, and may not be without interest to the historian, it is here inserted in the same form in which it was given in evidence.

“These are to certify all whom it may concern that William1 Penn Esqr. Proprietor and Govr. of the provinces of Pennsylvania and the territories thereunto belonging at his first arrival from England by the Town of New Castle upon Dellaware River in the month of October anno 1682 did send then and there our messenger ashoar to give notice to the Commissioners of his desire to speak with them aboard (I being then left the first in Commission by Sr. Edmund Andross Governour Genl. under his Royal highness James Duke of York and Albany etc. of all his Territorys in America) did go aboard with some more of the commissioners att which time Esqr. Penn did show me two sundry Indentures or Deeds of Enfeoftment from under the hand and seal of his Roy-all Highness granted unto him, both bearing date the 28th day of August Anno 1682 the one for the county of New Castle with twelve miles distance North and South thereunto he-longing and the other beginning twelve miles 1130below New Castle and extending South unto Cape Henlopen together with the mills and waters of the said River, Bay, Rivulets and the Islands thereunto belonging &c. underneath both which sd. Indentures of deeds of Infeoftment were added his Royall highness letters of attorney directed unto me and Ephraim Herman deceased with full power and authority for to give in his Royall highnesses name unto the sd. William Penn Esqr quiet and peaceable possession of all what was Inserted in the sd. Indentures as above briefly is specified. But the sd. Eph. Herman happened to be gone from home so that he was not at that time aboard with me of the sd. ship, I therefore did desire from Esqr Penn four and twenty hours consideration for to communicate with the sd Herman and the rest of the Commissioners about the premises. In which compass of time we did unanimously agree to comply with his Royal Highnesses orders whereupon by virtue of the power given unto us by the above mentioned letters of Attorney We did give and surrender in the name of his Royall Highness unto him the said William Penn Esq actual and peaceable possession of the fort of New Castle by giving him the key thereof to lock upon himself alone the door which being opened by him again We did deliver allso unto him one turf with a twigg upon it a porringer with River water and Soyle in part of all what was specified in the sd. Indenture or Deed of Infeoftment from his Royal Highness and according to the true intent and meaning thereof. And few days after that we went to the house of Capt. Edmund Caulwell at the south side of Appoqueniming Creek by Computation above twelve miles distance from the Town of New Castle as being part of the two Lower Countys here above mentioned and specified in his Royal Highnesses other Indenture or Deed of Infeoftment and after we had shown unto the Commissioners of these Countys the power and orders given unto us as aforesaid we asked them it they could show us any cause why and wherefore we should not proceed to act and do there as we had done at New Castle, and finding no manner of obstruction We made then and there in his Royal Highnesses name the same manner and form of delivery as we had done at New Castle Which acting of us was fully accepted and well approved off by Anthony Brock-hold then Commander in chief and his Council at New York as appears by their Declaration bearing date the 21st of November 1682, from which Jurisdiction we had our Dependance all along ever since the Conquest untill we had made the above related delivery unto Governour William Penn by virtue of his Royall highnesses orders and Commands &c.

“Jno. Moll.”

The declaration of November 21, 1682, referred to in the foregoing certificate, was a circular letter (3 Hazzard. Pa. Reg. 34) by Captain Brockhold, &c, to the several justices of the peace, magistrates and other officers of Delaware, which, after reciting the two deeds of August 24th from the Duke of York to William Penn,—mentioning one of them as granting “all that town of New Castle otherwise called Delaware, and all that tract of land lying within the compass or circle of twelve miles about the same, with all islands and the river and soil thereof lying north of the southernmost part of the said circle,”—which deeds are spoken of as having been “here produced and shewn to us, and by us well approved and entered in the publick records of this province,”—proceeds to say that “we being fully satisfied of the said William Penn's right to the possesment. Expecting no further account than that you readily submit and yield all due obedience and conformity to the powers granted to the said William Penn in and by the said indenture, in the performance and enjoyment of which we-wish you all happiness.”

So far as to the title derived to Mr. Penn-from the grants of 24th August, 1682, prior to certain letters patent now to be mentioned, from King Charles II. not to Mr. Penn—but to the Duke of York—granting, March 22, 1683, to him, the same property which the duke had' granted about seven months before to Mr. Penn. 2 Hazzard, Pa. Reg. 27. The letters-patent describe the territory as “all that the town of New Castle otherwise called Delaware, and fort therein or thereunto belonging, situate, lying and being between Maryland and New Jersey, in America. And all that tract of land lying within the compass or circle of twelve miles about the said town, situate, lying and being upon the river of Delaware. And all islands in the said river of Delaware. And the said river and soil thereof, lying north of the southernmost part of the said circle of twelve miles about the said town. And all that tract of land upon Delaware river and bay, beginning twelve miles south from the said town of New Castle otherwise called Delaware, and extending south to Cape Lopin. Together with all the lands, islands, soil, rivers, harbours, mines, mineral, quarries, woods, marshes, waters, lakes, fishings, hawkings, huntings, and fowlings, and other royalties, privileges, profits, commodities and hereditaments to the said town, fort, tracts of land, islands and premises, or to any or either of them belonging or appertaining, with their and every of their appurtenances, situate, lying and being in America. And all our estate, right, title, interest, benefit, advantage, claim and demand whatsoever, of, in or to the said town, fort, lands or premises, or any part or parcel thereof. And the reversion and reversions, remainder and remainders-thereof, together with the yearly and other rents, revenues and profits of the premises and of every part and parcel thereof. To have and to hold the said town of New Castle otherwise called Delaware, and fort, and all and singular the said lands and premises, with their and every of their appurtenances hereby given and-granted, or hereinbefore mentioned to be given-and granted, unto,” &c.

These letters patent gave powers of government in the same way as those of March 12, 1683-84, to which, except in the description of the property granted, their language almost exactly conformed.

The original of this patent from the king to the duke8for Delaware, and of the Duke of York's grant to Penn for the twelve miles circle were produced before the arbitrator; having both, with the original charter of Pennsylvania and two leases of August 24th to Mr. Penn, mentioned ante, p. 1129. note, been brought to Philadelphia, about the year 1834, by Mr. Coates of that city, an agent of the estates in” Pennsylvania belonging to Mr. Penn's descendants in England. Mr. Coates got possession of them on a visit to his principals in England. Being at their seat of Stoke Pogls, he was shewn by them into the charter-room of their house, where he was told that he might find some old deeds &c. that would interest him as an American, and to which he was welcome. Happening to find the patents and deeds just mentioned, he brought them to Philadelphia, where those relating to Delaware still were, on the hearing of this case.

It appeared also, by an original “Breviate” of the Hon. Mr. Murray, A. G. and Sir Dudley 1131Ryder, S. G. solicitors for the sons of William Penn in their suit with Lord Baltimore—(1 Ves. Sr. 444) before Lord Hardwicke, A. D. 1750; the bill was filed June 21, 1735—that these identical parchment letters patent were in evidence before Lord Hardwicke in that case as the complainants' exhibit. And were put in evidence by them to shew their possession of them, and so repel an objection of Lord Baltimore's, that “the duke obtained this grant for himself and not for Mr. Penn, and never made any subsequent conveyance to Mr. Penn.” Breviate.

The counsel of the United States, in order to shew that the title of the Penns as thus derived, had been subsequently recognized and confirmed by the crown, and had been asserted also by the state of Delaware just at the time of the American Revolution, then referred to certain facts of history as follows:

Penn was the intimate friend of James II. and in favour at the English court until the accession of William and Mary. In 1692 his government in America was taken from him, and Benjamin Fletcher appointed in his place. Fletcher gave dissatisfaction, and Penn was restored to his government again, in 1694, by letters from William and Mary. 1 Proud's Hist. Pa. 377, 403.

Charles I. having granted to Lord Baltimore in 1632, a tract of land between the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays, a dispute arose between Penn and him as to the extent of the king's grant and the situation of the line between them. Lord Baltimore's grant, reciting that the earl, being desirous to extend the Christian religion as well as the English empire to certain parts of America, hitherto savage, and inhabited by people having no knowledge of the Divine Being, had asked the king for that region—gave to him all the country being between the Chesapeake and Delaware Bays. An application having been made to the crown for a grant to the Duke of York, “of the parts adjacent to the Delaware Bay,” Lord Baltimore, by his agent Mr. Burk, applied, May 21st, 1683, praying that the grant might not pass until the king should he satisfied as to the extent of the grant already made to the earl. The minute then proceeds (1 Votes Pa, Assem. xiv), May 30, 1683: “Counsel learned, in behalf of his royal highness, together with an agent from Mr. Penn, who solicits the passing of this grant; as also the petitioner, Mr. Burk, and his counsel learned, are called in: whereupon the counsel for my Lord Baltimore, affirming that the tract of land in question, lies within the limits of the charter granted to the Lord Baltimore, and that his lordship has always continued his claim thereunto; Mr. Penn's agent, and the counsel in behalf of his royal highness, endeavoured to make out, that the territory was never possessed by my Lord Baltimore, but originally inhabited by Dutch and Swedes; and that the grant to my Lord Baltimore, was only of lands not inhabited by Christians; so that a surrender having been made to his majesty in 1664, the Lord Baltimore can have no rightful claim thereunto; and that it having been ever since in the possession of his royal highness, the Lord Baltimore can receive no injury by the grant that is desired. Upon the whole matter, Mr. Penn's agent undertaking to prove within a short time, that this country was possessed by the Dutch and Swedes, in the year 1609, or at least before the date of the Lord Baltimore's patent, their lordships agreed to meet again as soon as the proofs shall be ready for making out the same.” After numerous hearings, in which it appears that the Duke of York, the earl and Mr. Penn, all took part, a final order was made November 7, 1685, as follows (1 Votes Pa. Assem. xviii).: “My Lord Baltimore and Mr. Penn, attending concerning the boundaries of the country of Delaware, are called in; and being heard, their lordships resolve to report their opinion to his majesty, that, for avoiding of further differences, the tract of land lying between the river and Bay of Delaware and the eastern sea on the one side, and Chesapeake Bay on the other, be divided into two equal parts, by a line from the latitude of Cape Henlopen to the fortieth degree of northern latitude; and that one-half thereof lying towards the Bay of Delaware, and the eastern sea, be adjudged to belong to his majesty, and that the other half remain to the Lord Baltimore, as comprised within his charter.”

This being done, articles of agreement were concluded in 1732, between the Earl of Baltimore and the sons of William Penn, upon which the Penns, in 1735, filed their hill in chancery in England, praying for a specifick performance and the running and settlement of the boundaries. This bill set forth title in the Penns; the Duke of York's and the king's deeds, (giving their dates and the description of the property conveyed, including the river, soil, and islands north of the southernmost part of the twelve miles circle,) the delivery of seizin by Moil, the circular letter by Captain Brockhold the covenant in the duke's deed for further assurance, and alleged that “immediately after the said last recited letters patent had passed the great seal, the said Duke of York, who was no other than a trustee for the said William Penn therein, and had obtained them in pursuance of his covenant for further assurance, did deliver over the same original last recited letters patent under the great seal to the plaintiffs father;” that after this, and when the duke was soliciting from the king a more beneficial grant for Penn, which was then preparing in order to pass the great seal, the same was stopt by Lord Baltimore, whose petition caused the matter to be referred by the king to the committee of trade and plantations, where both parties were heard for nearly two years and a half: that it is continually taken notice and expressly mentioned in the minutes made by the said committee thereon, that the dispute was a dispute between Baltimore and Penn, though the latter did sometimes use the Duke of York's name, and though the duke himself did by his counsel and other agents sometimes assist and interpose in the suit: which latter fact the Penns rely on as a manifest proof that the duke held the king's letters patent for the benefit of Penn and not of himself. And finally, that, November 7th 1685, the committee made the adjudication already mentioned.

That notwithstanding this, Lord Baltimore in Jan. 1708, brought the matter before Queen Anne, who, after a counter-representation from Penn, dismissed the petition in the same month; that not yet satisfied, the earl, in May 1709, presented the matter again to the queen, who ordered it to be heard before her in council, where both Penn and Baltimore were heard, and where it was ordered that the earl's petition be dismissed, and that the order of November 7th 1685, be ratified and confirmed in all its points and put in execution.

The case, which is the well known case reported in 1 Ves. Sr. 444, under the name of Penn v. Lord Baltimore, was heard before Lord Hardwicke who, May 15th 1750, decreed in favour of the Penns, but “without prejudice to any prerogative, power, property, title or interest of his majesty, his heirs and successors in or to the said territories, &c.” (Belt, Supp. Ves. Sr. 198), with liberty, in case the king should insist on any power, &c. for any of the parties to apply. Subsequent articles of 1760, and another chancery decree, twelve years later, terminated the dispute between the parties.

In 1767, the Penns and Lord Baltimore presented a joint petition to George III. reciting the before mentioned articles and decrees, and setting forth that the commissioners to run the line were proceeding in their work, and praying the king to give his allowance, ratification and confirmation of the articles and decrees 1132already mentioned; whereupon the king, January 11, 1769, by order in council, signified his approbation of the proceedings mentioned in the petition.

On the 8th April, 1775, John Penn, then governour of Pennsylvania and Delaware, or the lower counties as they were then called, made a proclamation making known the premises, and on the 2d Sept., 1775, it was enacted by the legislature of the lower counties, in an act reciting the articles of agreement, decrees and proclamations, that certain lines which were then fixed, should be the divisional lines of the counties. The act does not profess to fix either the eastern or the western bounds of the province. 1 Booth's Laws Del. 567, 569.

The paper title of the United States was completed by an act of assembly of the state of Delaware, May 27, 1813; by which it was enacted, that “all the right, title and claim, which this state has to the jurisdiction and soil of the island in the Delaware commonly called the Pea Patch, be and the same is hereby ceded to the United States of America, for the purpose of erecting forts, batteries and fortifications for the protection of the river Delaware and the adjacent country,” &c. &c. reserving jurisdiction, &c. Dig. Del. Laws (Ed. 1829) p. 673.

The same counsel, in order to show, more specifically, that absolute control over the whole river within the twelve miles circle, had been, at least, claimed from early days by the lower counties, proved that about the year 1707, a law was passed at New Castle, whereby a tax of half a pound of powder for each ton of measurement, was laid upon every vessel bound up or down the river; that the lower counties proceeded to enforce the tax by firing upon vessels which would not pay it; that although the general assembly of Pennsylvania strongly remonstrated against the matter, the law was never repealed, though its execution was stopped by defiance and resistance from Pennsylvania vessels. 1 Votes Pa. Assem. pt. 2, p. 170.

So far as to the paper title of the respective parties, as the same was proved by original deeds or early legislative action.

As to the jurisdiction exercised, de facto, in the river, it appeared on behalf of New Jersey that Egg Island, a small island low down in Delaware Bay, and Stypson's Island, whose position could not be found by counsel, but both of which wore admitted to be without the circle, were held under New Jersey, though how, or for how long, did not appear. Further, that some time since 1832, a boat-man having committed an assault upon some person on the river within the circle, a constable of New Jersey pursued the criminal to the Pea Patch and arrested him. “The constable had process,” that is, said the witness, a military person, “he had a pistol; he shewed no process but that.” The boat-man refused to go to New Jersey, said he would go on lawful process; process from Delaware; and did not go with the constable, who went away and never came back after him. On the part of Delaware, the evidence was more full. Reedy Island and Bombay or Boonprie Hook, the only island within the circle, had always, so far as appeared, been considered as part of Delaware, to which state the people also were considered as belonging. Both these islands, however, lie close to the Delaware main land; the latter being within its profile, and separated from it only by an artificial cut or canal.

Twelve persons were examined from the state of Delaware, most of them aged, and likely, it was said, from their professions or pursuits to be acquainted with the fact of what jurisdiction generally had been exercised over the circle by Delaware, for the last seventy years or more.

Among them was' the Hon. Thomas Clayton, aged seventy years and upwards, sometime a member of the legislature of Delaware, afterwards attorney general and then chief justice of that state, and more recently its representative in the senate of the United States. “It has been held,” said this witness, who had resided all his life in Delaware, “it has been held, as far back as my memory goes, by the courts, publick officers, and lawyers of Delaware, that the title and jurisdiction of the state of Delaware extended to a circle of twelve miles around New Castle, to low water mark on the New Jersey shore. I never heard the title or jurisdiction of the state doubted, over that part of the river Delaware, by any one, until the claim of Doctor Gale was set up to the Pea Patch; and since that, I have heard no one in the state of Delaware, lawyer or other, doubt it. Writs have been issued by the courts of Delaware to seize vessels and persons in all parts of the river indiscriminately, within the twelve mile circle, and I never knew such a seizure to be disputed in any court of Delaware, on the ground of want of jurisdiction over all such parts of the river.”

James Rogers, Esquire, sixty years old, for most of his life a resident in or near New Castle, and for twenty years attorney general of Delaware, testified as follows: It has been uniformly considered by the courts, publick officers and lawyers of the state of Delaware, that her title and jurisdiction extended within a twelve mile circle around New Castle, to low water mark on the Jersey shore. I have never heard her title or jurisdiction over that part of the river Delaware doubted by any court, publick officer or lawyer in Delaware. I know that writs have been often issued from the courts in Delaware for New Castle county, and that by vritue of such writs, persons, vessels and cargoes have been arrested and seized within the jurisdiction above alluded to; and in no instance, within my knowledge, was the jurisdiction ever disputed, or any question made as to the jurisdiction of the state, when such persons were arrested or vessels and cargoes seized. I have in many cases caused writs to issue and persons to be arrested, and vessels and cargoes to be attached and seized upon the river Delaware, and within the aforesaid jurisdiction, and have been concerned in cases where process of attachment has been issued by other members of the bar. I recollect one case, in the supreme court,—Richards v. Dusar. I was counsel for the defendant, and every defence was set up that was considered available, but no plea to the jurisdiction was set up.” (The record of this suit was attached to Mr. Rogers' deposition, and showed that four pleas had been put in.)

“With respect to lands held by warrant, survey and patent, from William Penn and his heirs, the title has been universally held as good title. It has been always held by our courts that the Penn title, under the Duke of York, was the true title to the lands and waters in Delaware, so far as my knowledge extends. I know no other title than the Penn title, a few titles held by grant from the aborigines and from the state excepted.”

The HONOURABLE JAMES BOOTH, chief justice of Delaware, aged fifty-seven years, who was born in New Castle, and, with the exception of four years had resided there all his life, testified to the same effect, essentially, as to the jurisdiction, though in language more qualified than Mr. Rogers. On the subject of the Penn title he added: “There never was any doubt or question, so far as my knowledge and information extends, of the justice and legality of the Penn title, under the Duke of York, to the lands within the state of Delaware. It was always considered, in this state, the true title to the lands and waters in the state of Delaware; although I have seen on record some old title papers for lands from the aborigines of the country, and from Sir Edmund Andross, before the date of the deed from the Duke of York to William Penn. I have seen many titles incepted 1133in court by the Penn warrants, surveys, and patents, and have always understood and believed that all lands and waters in the state of Delaware, within the twelve miles circle, are held under the Penn title.”

The testimony of Kensey Johns, Esquire, was particularly relied on by the counsel of the United States, as well from the venerable ago to which this witness had attained, as from his most respectable understanding, attainments and character, and from the great opportunities which he had had of becoming acquainted with the subjects on which he spoke. “I was eighty-eight years and four months old,” said this witness, “on the fourteenth day of last month, (October, 1847.) I reside in the town of New Castle, in the state of Delaware. I have resided here since the year 1780. My business has been a practising lawyer for twelve years; afterwards, chief justice of the supreme court of the state of Delaware for thirty-eight years: afterwards, chancellor of the state: since that time and at present living a private gentleman.”

“I have known the island since the year 1780. At first it appeared about the size of a man's hat. In 1813, when the United States took possession of it, it had grown to be a large island. It was not worth a cent to any private citizen. The expense of banking would have been more than it was worth. It has always been considered and held,” continued the ex-chief justice and chancellor, “by the courts, publick officers, and lawyers of Delaware, as far of my memory reaches, that the title and jurisdiction of the state of Delaware extended to a circle of twelve miles around New Castle to low water mark on the New Jersey shore. I have never heard the title and jurisdiction of the state of Delaware over that part of the river Delaware doubted by any court, publick officer, or lawyer in Delaware on any occasion whatever. Within my knowledge and remembrance, writs have been often issued out of the courts of Delaware to seize vessels and persons in all parts of the river Delaware within the circle of low water mark on the New Jersey shore; and no dispute, question, or plea was ever made or suggested, within my memory, before any court in Delaware against the title and jurisdiction of Delaware over all such parts. The state of Delaware, for the whole period of my remembrance, and as far as my researches extend, has claimed and exercised title and jurisdiction over the Delaware river and soil thereof, within the circle to low water mark on the Jersey shore, and the state has never failed to exercise this jurisdiction when called upon or asked to do so.”

“The lands in Delaware generally are held under the title of William Penn and his heirs. The Penn proprietors granted title by warrant, survey, and patent. In action of trespass or ejectment, the plaintiff incepted his title by the warrant and survey. I never heard of any doubt, in the courts of Delaware, of the justice and legality of the Penn title to the lands in the state of Delaware. It has always been held as the settled maxim within the Delaware courts, that the Penn title, under the Duke of York, was the true title to the lands and waters in Delaware. I have seen a great many (I can't say how many) titles incepted in court by the Penn warrants and surveys. The lands and waters generally in Delaware within th & twelve mile circle, are held under the Penn title.”

In addition to the above testimony which, so far as it spoke of the circle generally, was corroborated to some extent by records, there were three or four well attested instances of process which issued from the state of Delaware having been served close upon the Jersey shore.

Mr. Thomas Janvier, aged seventy-five, a resident of New Castle, and for some years engaged in trade there, said: “It is within my memory that R. C. Dale, who was sheriff of New Castle county from 1803 to 1806, after summoning a posse, boarded a ship on her outward passage, and arrested a person on board of the ship after she had been run ashore on, the Jersey side, nearly opposite the town of New Castle; the names of the parties and the minute detail of the affair, I do not now remember. About twenty-five years since, I accompanied the deputy of the sheriff of New Castle county, and with him boarded a sloop then, between the Pea Patch Island and the Jersey shore, and was with the deputy sheriff when he arrested the captain of the sloop by virtue of a writ, issued out of one of the courts of Delaware. The matter was compromised with me, the captain of the sloop paying the demand, and we let him go.”

Mr. Wm. Robinson, aged sixty-five, residing: all his life in New Castle county, stated that about the year 1834, he “accompanied the deputy sheriff, in a boat, for the purpose of arresting a person on board a schooner that was coming down close on the Jersey shore; the deputy sheriff boarded the vessel in that situation, and arrested the captain. The matter was compromised, and the captain was discharged from the arrest, on his paying some amount of damages claimed of him for running into a sloop laying at anchor off this town.”

Mr. John Steel of Philadelphia, aged sixty-seven, who kept a shop in New Castle in 1800, gave the following account of an arrest made within his knowledge: “While residing at New Castle, I had occasion, in July or August 1800, to serve process on a man who was boatswain of the United States ship Scammon. I took the advice of George Read, Esq., district attorney of the United States, a lawyer of eminence in Delaware. He told me to follow the man as far as low water mark on the Jersey shore, but no further. I went over after the man, and caught him at the end of the wharf in his boat as he was going-ashore. He was outside of low water mark at the wharf. I brought him back to New Castle, and he gave me an order to the officer at Washington for his back wages. I sent this order on to Washington, and got the money for it. There were people who professed to know how to keep clear of process from Delaware; they would steer close to the Jersey shore. Our custom was, in suing people, always to take process from Delaware. We never got any from Jersey. I was on terms of intimacy with the sheriff; boarded in his house a part of the time. Our instructions were never to go beyond the Jersey low water mark. I never knew any dispute about the jurisdiction. It was the well settled opinion in them days that the jurisdiction extended to low water mark on the Jersey shore. The man whom I arrested never sued me for trespass. He had a lawyer with him; Mr. Brown, perhaps, of Philadelphia, then a young man; or-it might have been a student of Mr. Bayard's.”

It further appeared that one Cockrin, in the employ of the United States and residing on the Pea Patch as tenant or agent had been regularly assessed, had paid taxes and voted from 1836 to 1847, in Red Lion hundred, New Castle county, Delaware, and that his vote had never been challenged.

Touching the position of the island in regard to “the main channel,” twelve persons, river-pilots or captains of small vessels, testified that the western or Delaware channel was the main channel, that it was always so considered by all navigators, “always had been and always would be,” said one witness; and that large vessels almost invariably took it, whether the wind was fair or adverse. They stated, however, that when the tide was high, and the wind fair, large vessels, if well navigated, could pass on the other side, as it was admitted that the United States ship of war, Pennsylvania, the largest which ever floated in the 1134waters of the United States, had done in 1836, under those circumstances: but that vessels which could beat through the other, could not do so at all through this. The Jersey channel, it appeared was broad and very deep for a few rods just opposite the island, but at its head, in consequence of the Bulk-Head shoal, grew narrow, and therefore less safe. The Delaware channel was soft; the Jersey one hard. The statement received by consent, of Mr. Wilson M. O. Fairfax, of the United States coast survey, which had been recently made, was thus: “The main and deepest channel of the Delaware-river opposite the Pea Patch is on the Jersey side. The greatest depth of water in the channel on the Jersey side is 40 feet, and on the Delaware side 25 feet. The average depth of water in the channel of the Jersey side is 32 feet, and on the Delaware side 23 feet. But to take the entire channel on either side of the island, no vessel drawing more than 19 feet water at low water of spring tides can pass through. The Jersey channel is the shortest and widest, and both about equally curved.”

Touching the position of the island in regard to the two shores, it appeared that the Jersey shore had been constantly washed away within the last half century, and so receding from the island; that drawing a line midway between the shores,  acres of the island were on the Delaware side,

acres of the island were on the Delaware side,  on the New Jersey side; that the north extremity of the island would be 2090 yards from the Delaware shore, and 2130 yards from the New Jersey shore: the south extremity 2197 yards from the Delaware shore, and 1875 yards from the Jersey shore. And that the area of the island is

on the New Jersey side; that the north extremity of the island would be 2090 yards from the Delaware shore, and 2130 yards from the New Jersey shore: the south extremity 2197 yards from the Delaware shore, and 1875 yards from the Jersey shore. And that the area of the island is  acres.

acres.