741

Case No. 18,113.

WYMAN v. BABCOCK.

[2 Curt. 386.]1

Circuit Court, D. Massachusetts.

May Term, 1855.2

ABSOLUTE DEED AS MORTGAGE—ORAL EVIDENCE—DENIALS IN ANSWER—EQUITT OF REDEMPTION—PRESUMPTION OF RELEASE—LAPSE OF TIME—CONSTRUCTIVE TRUST.

1. A deed, absolute in form, may be shown to have been really a mortgage, by the oral testimony of two witnesses, against the denials of the answer, where those denials are not satisfactory in themselves, and are accompanied with admissions that some confidential relations existed between the parties, not consistent with the terms of the deed. The statutes of Massachusetts, as to the foreclosure of mortgages, apply only to legal mortgages.

[Cited in Andrews v. Hyde, Case No. 377; Amory v. Lawrence. Id. 336.]

[Cited in Newton v. Fay, 10 Allen, 509; Campbell v. Dearborn, 109 Mass. 139.]

2. The presumption that an equity of redemption is released after twenty years' possession by a mortgagee, does not apply to a case where the mortgagee was in possession under an absolute deed, with an agreement that the mortgagor might redeem when he found it convenient, no specific time being fixed, and the mortgagee had no notice or request to redeem. And if, in such case, the mortgagee sells the land to a bona fide purchaser, and so destroys the equity of redemption, a court of equity treats him as a constructive trustee, so the trust is not barred till the expiration of six years from the discovery of the right to an account.

[Cited in. Amory v. Lawrence, Case No. 336.]

[Cited in brief in Walker's Adm'r v. Farmers' Bank, 6 Del. Ch. 81, 10 Atl. 96. Cited in Linnell v. Lyford, 72 Me. 284; Hinckley v. Hinckley, 9 Atl. 898, 79 Me. 323.]

In equity.

S. Bartlett and S. Ames, for complainant.

C. G. Loring and Wm. Dean, contra.

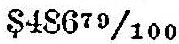

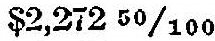

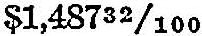

CURTIS, Circuit Justice. This is a suit in equity by Edward Wyman, a citizen of the state of Missouri, as assignee of Nehemiah Wyman, his father, against Archibald Babcock, a citizen of the state of Massachusetts. The bill states that, on the 20th day of November, 1828, Nehemiah Wyman was seized of a tract of land in Charlestown, containing about eleven acres and a half; that about one acre of this land had been sold and conveyed by him to James Foster, who, having mortgaged it back to secure the payment of the consideration money, Nehemiah Wyman had entered for breach of condition, and to foreclose the mortgage; that all but the Foster one was incumbered by two mortgages, both held by the defendant; the first being a mortgage from Nehemiah to Francis Wyman, on which there was then due for principal and interest the sum of  , the defendant, being the executor and trustee under the will of Francis Wyman, in that right holding this mortgage; and the second being a mortgage from Nehemiah to the defendant, nominally to secure the sum of $1,200 and interest, but really to secure the repayment of such sums as might be advanced by the defendant to Nehemiah; and that on this last-mentioned mortgage there was then due, for such advances, the sum of four hundred dollars. The bill further states, that at the same time, Nehemiah also owed to the defendant, personally, eight dollars

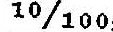

, the defendant, being the executor and trustee under the will of Francis Wyman, in that right holding this mortgage; and the second being a mortgage from Nehemiah to the defendant, nominally to secure the sum of $1,200 and interest, but really to secure the repayment of such sums as might be advanced by the defendant to Nehemiah; and that on this last-mentioned mortgage there was then due, for such advances, the sum of four hundred dollars. The bill further states, that at the same time, Nehemiah also owed to the defendant, personally, eight dollars  , and to him, as agent for the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman, senior, the sum of one hundred and thirty-six dollars

, and to him, as agent for the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman, senior, the sum of one hundred and thirty-six dollars  ; that Nehemiah was much embarrassed in his affairs, and at the pressing solicitation of the defendant, who was his brother-in-law, and of William Wyman, his brother, he consented to make a deed of the said land, excepting the Foster acre, to the defendant, absolute 742in form, but intended to stand as security for what Nehemiah thus owed; that the conveyance was made for that purpose only, and the defendant went into possession; that none of the notes held by the defendant were surrendered or cancelled, the same being retained because the land was taken as security only; that the defendant was to have the management of the land and receive the rents and profits, and apply them towards the accruing interest; and if there should be any excess, towards the principal, and that Nehemiah was to have the right to redeem at any time when he should be able to do so. The bill further states, that in 1844 the defendant, without any notice to Nehemiah, of his intention to sell, or to the purchasers, of the nature of his title, sold the land by an absolute title, to bona fide purchasers, without notice; and it prays for an account of the rents and profits while held by the defendant, and of the value of the land when sold, and that after deducting the amount for which the land stood as security, the residue may be paid to the complainant, who alleges himself to be the assignee, by deed, for a valuable consideration, of all Nehemiah's equity in the premises.

; that Nehemiah was much embarrassed in his affairs, and at the pressing solicitation of the defendant, who was his brother-in-law, and of William Wyman, his brother, he consented to make a deed of the said land, excepting the Foster acre, to the defendant, absolute 742in form, but intended to stand as security for what Nehemiah thus owed; that the conveyance was made for that purpose only, and the defendant went into possession; that none of the notes held by the defendant were surrendered or cancelled, the same being retained because the land was taken as security only; that the defendant was to have the management of the land and receive the rents and profits, and apply them towards the accruing interest; and if there should be any excess, towards the principal, and that Nehemiah was to have the right to redeem at any time when he should be able to do so. The bill further states, that in 1844 the defendant, without any notice to Nehemiah, of his intention to sell, or to the purchasers, of the nature of his title, sold the land by an absolute title, to bona fide purchasers, without notice; and it prays for an account of the rents and profits while held by the defendant, and of the value of the land when sold, and that after deducting the amount for which the land stood as security, the residue may be paid to the complainant, who alleges himself to be the assignee, by deed, for a valuable consideration, of all Nehemiah's equity in the premises.

Upon this case, an outline of which, as stated in the bill, has thus been given, several questions have been made, and elaborately argued by counsel. The first question which arises is, whether the complainant has made out, in point of fact, that the land was conveyed by way of security as is stated in the bill. The answer denies that it was so conveyed. Two witnesses, Nehemiah Wyman, and his brother William Wyman, testify, directly and positively, in support of the statements made in the bill. Ordinarily, this would be sufficient to control the answer. But there are facts in this ease, which require me to examine the credibility of these witnesses, to compare their weight with that due to the answer, and to test both the answer and the proofs by their consistency with facts admitted or clearly proved, and to see how far the one or the other best accords with the surrounding circumstances. Nehemiah Wyman was, until a short time before the bill was filed, the owner of the equity asserted by this suit. He sold and conveyed his interest to his son; this purchase, the son was advised by counsel to make, in order that the father might be a witness. I see no sufficient reason to doubt that it was an actual sale, for a valuable consideration, which divested him of all interest. Nehemiah Wyman says is was not made to enable him to testify. As it appears, the son had communication with the counsel, and the father, who lived in a distant state, does not appear to have done so, perhaps the just conclusion is, that he did not know that was the inducement which led to the purchase by the son. But at all events, his relation to the cause is not that of an unexceptionable witness. William Wyman has acted as the agent of his brother, while he held the claim, and of his nephew since. He has had some difficulty with the defendant, who is the husband of his sister, about an account. It is apparent that his feelings are enlisted in favor of the claim.

Some supposed contradictions and inconsistencies in the testimony of the two witnesses were mentioned at the argument, and have been examined. My judgment is, that considering the lapse of time since the events testified to, and considering the relations of these two witnesses to the controversy, without imputing to either of them any intentional unfairness, I ought not to rest a decree, upon the unaided force of their testimony, against a satisfactory answer directly responsive to the bib. And therefore I must examine the answer, ascertain what are its claims to credence, and see whether it, or the evidence of these witnesses, is most credible in itself, and best consists with the known facts.

The account given in the answer of the purpose and consideration of the deed in question, is as follows:—“That this defendant at the urgent solicitation of the said Nehemiah, consented to accept said conveyance in payment of the sums of money due to him personally, and upon the agreement that if he should be able to realize therefrom in addition enough to pay the sums due to him as executor and trustee, he would pay the same, and upon no other agreement, trust, or confidence whatsoever. This defendant further says that upon the delivery to him of the said deed, he cancelled the notes of said Nehemiah Wyman, held in his own right, and either surrendered them to him or destroyed them, but that he did not cancel or surrender the notes held by him as executor and trustee, because he was not satisfied that he should realize enough of the said land to pay the same, and that in order to prevent any presumption that he had so agreed absolutely, he made a minute thereon to the effect that he did not guarantee payment thereof; it being the understanding and agreement between him and the said Nehemiah, that if enough was not realized out of said land to pay the whole of said debts, the said Nehemiah should be personally liable therefor, and that this defendant should, if possible, realize enough to pay the same, and should not be under any liability to account with the said Nehemiah for his doings relating thereto.”

The first observation which occurs on reading this statement is, that it is not consistent with the deed itself. That declares the consideration to be the sum of two thousand and thirty-three dollars and eighty-seven cents. The answer, in another place, admits that, “the consideration money expressed in the deed was the amount then due to the defendant in his own right and as executor and trustee, and of the further sums of 743eight dollars  owed to this defendant, and fifty dollars owed to him as agent for the heirs;” and there is no doubt whatever how the amount expressed in the deed was arrived at, and that it was by a careful computation of the principal and interest due, at the date of the deed, to the defendant in his own right as executor and trustee, for the children of Francis Wyman, and as agent of the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman. If the above statement in the answer is correct, it is difficult to perceive how the debt due to the defendant as executor and trustee, for which the land was already mortgaged, formed any part of the consideration of this deed, or why it was said by the deed to do so; and still less why the amount due to the defendant as agent for the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman, senior, was included in the consideration; for according to the answer, there was no agreement at all concerning the application of the land, or its proceeds, to that debt.

owed to this defendant, and fifty dollars owed to him as agent for the heirs;” and there is no doubt whatever how the amount expressed in the deed was arrived at, and that it was by a careful computation of the principal and interest due, at the date of the deed, to the defendant in his own right as executor and trustee, for the children of Francis Wyman, and as agent of the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman. If the above statement in the answer is correct, it is difficult to perceive how the debt due to the defendant as executor and trustee, for which the land was already mortgaged, formed any part of the consideration of this deed, or why it was said by the deed to do so; and still less why the amount due to the defendant as agent for the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman, senior, was included in the consideration; for according to the answer, there was no agreement at all concerning the application of the land, or its proceeds, to that debt.

It was suggested by the defendant's counsel that there was a mistake made in drawing the answer, and that instead of speaking of what was due to the defendant as executor and trustee, it should have said as agent. But I must take the answer as it stands. If there was any such mistake, there is an established mode of obtaining leave to correct it, and proper guards and securities are thrown round such applications. Smith v. Babcock [Case No. 13,008]; 2 Daniell, Ch. Prac. 911. But it cannot be done at the hearing; and requires more than a suggestion of counsel to obtain it, however probably correct that suggestion may be. Besides, if the proposed change were made, it would only increase the difficulty above adverted to; for then it would stand that there was no agreement concerning the greater amount, due to the defendant as executor and trustee, and yet it formed part of the consideration expressed in the deed.

The next circumstance which has attracted my attention is, that this part of the answer declares that the defendant took the land in payment of what was due to himself personally, “and upon the agreement that if he should be able to realize therefrom enough to pay the sums due to him as executor and trustee, he would pay the same.” If this were so, then the heirs of Francis Wyman, whom the defendant represented as executor and trustee, acquired an interest in the land, which by the agreement, was to stand as security for the debt due to the defendant as executor and trustee, after enough should be received therefrom to pay his own debt. Yet when the defendant afterwards answered further, in consequence of exceptions to his original answer, in speaking of the proceeds of the sales of the land, he says, that he paid the two thousand dollars received of Hall, (one of the purchasers,) to said heirs, (of Francis Wyman,) on account of his liability to said heirs as their trustee, and not on account of any right they had to the said land or to the proceeds thereof, and that he used all the said money paid to him, as aforesaid, as his own money, as he had a right to do. As the proceeds of these sales very greatly exceeded what was due to the defendant personally, it is difficult to reconcile this, with the admission in the original answer, that he did agree to appropriate what he should be able to realize from the land, in addition to his own claim, to the payment of the sums due to him as executor and trustee; or to see how he could consider that his own money, to be used as he saw fit, which he had agreed to appropriate to pay notes on which Nehemiah Wyman was personally responsible.

There are also some singular incongruities in the defendant's statement of the agreement, in the passage above quoted from the answer. It is, in substance, that the defendant took the land in payment for what was due to him personally, and agreed that if he should be able to realize from the land enough to pay the sums due to him as executor and trustee he would thus pay the same; that Nehemiah was to remain personally liable if the whole of what was due to the defendant as executor and trustee was not paid out of the land; and that the defendant was, if possible, to realize enough to pay the same; but he adds that he was not to be under any liability to account to Nehemiah for his doings relating thereto. How it was to be ascertained, without a sale, whether the defendant could possibly realize from the land more than enough to pay his own debt, and how much more he could so realize; how the obligation to sell and apply the proceeds as stated, can consist with his absolute acquisition of the title in payment of his own debt, and how the agreement to realize enough, if possible, to pay the debt due to him as executor and trustee, could have any efficacy whatever, if, as he declares, he was not to be under any liability to account with Nehemiah for his doings relating thereto, I am not able to perceive.

These particulars in the answer are not matters drawn from collateral statements; they grow out of that part of it which undertakes to set forth the agreement which is in controversy. They affect the substance of the transaction; and I am obliged to conclude that the account which the defendant has given in his answer, of the purpose and consideration of this deed, is not probable in itself, and is scarcely reconcilable with what men of ordinary knowledge of affairs would agree to; for its substance and effect, as stated in the answer, would be, that Nehemiah Wyman conveyed to the defend; ant, land worth, as the answer admits, $1,900, in payment of a debt of about $400; and though the defendant agreed he would, if possible, pay, out of the land, a debt of up-j wards of $1,400, for which Nehemiah stood personally liable upon his promissory note, 744yet the defendant was never to be called to account, and might keep this agreement or not, at his own pleasure.

Such a transaction is not only improbable in itself, but, considering the relations of the parties to it, would be so inequitable, that a court of equity could not allow it to stand. It must be remembered that this land was mortgaged by Nehemiah Wyman by two mortgages; the first held by the defendant as executor and trustee, and the second in his own right; and that both were then payable, and the defendant had power to bring suits on the notes and to enter for condition broken, and to foreclose. Now, according to the answer, the equity of redemption was released for no real consideration whatever; for if we take the debts due to the defendant personally to have been extinguished by this conveyance, while the much larger debt due on the first mortgage was kept alive, what did Nehemiah gain? He parted with land, admitted to be worth $1,900, to pay a debt of $400, leaving himself personally liable for the debt of 81,400, which the defendant might pay out of the land, or not, as he should elect. In Russell v. Southard, 12 How. [53 U. S.] 154, the court had occasion to consider the subject of a release of an equity of redemption by a mortgagor to a mortgagee, and set aside such a release, under circumstances certainly not so inequitable as this answer discloses. For there, the mortgagor simply got nothing for his release; here, according to this answer, he was subjected to a loss of $1,500, at the pleasure of the mortgagee.

Looking further at these statements in the answer, we find the defendant declaring that he did not surrender or cancel the notes held by him as executor and trustee, because Nehemiah was to continue personally liable thereon, but that he did cancel or surrender the notes held by him personally; if so, it would have been consistent with the agreement on which the conveyance was made, as he states it; but the fact does not appear to be so; all the notes remained in his possession, and uncancelled. This is a very significant fact. It is not consistent with the agreement to receive the deed in payment of some of these notes. According to the usual course of dealing among men of common prudence the retention of all these notes is consistent only with the hypothesis that the land was taken as security.

I attach some importance also to the dates of some of these notes. One of them,  is dated November 7th, 1828; and two others, one for eight dollars

is dated November 7th, 1828; and two others, one for eight dollars  , and the other for fifty dollars, are dated. November 11, 1828, and all bear interest. It is testified by William Wyman, and there is no evidence to the contrary, and it is in itself probable, that this conveyance was under negotiation for some time. The deed bears date on the 20th of November, 1828. If it was intended it should stand as a security, there was reason for reducing the debts to the permanent form of notes bearing interest, which the defendant could retain, as he in fact did retain them; if it was intended to receive the deed in payment of these debts, it is not probable they would have been put into this form, pending the negotiation.

, and the other for fifty dollars, are dated. November 11, 1828, and all bear interest. It is testified by William Wyman, and there is no evidence to the contrary, and it is in itself probable, that this conveyance was under negotiation for some time. The deed bears date on the 20th of November, 1828. If it was intended it should stand as a security, there was reason for reducing the debts to the permanent form of notes bearing interest, which the defendant could retain, as he in fact did retain them; if it was intended to receive the deed in payment of these debts, it is not probable they would have been put into this form, pending the negotiation.

The defendant's counsel has very forcibly urged the improbability that the defendant, who had security oh the land by a second mortgage for his own debt, and also by a first mortgage for the debt due to him as trustee, should have been willing to enter into an arrangement by which payment was so long, and almost indefinitely, postponed, There is much apparent weight in this argument; but it is lessened, on further examination of all the circumstances. Francis Wyman's will was such that, the principal debt was to remain invested, until 1842, and if this was a secure investment, as it is evident it was, its permanence was very desirable. Moreover, as the defendant himself states the transaction, he actually did agree to postpone the payment of that debt to the payment of his own, and to make its payment dependent on what he might realize from the land, at some indefinite time, when he might think it proper to sell. As to his own debt, as well as the debt due to him as a trustee, it must not be forgotten that this was a family arrangement, and that Nehemiah Wyman was poor and embarrassed, and had a large family. The same considerations of a rigid self-interest, which might be safe guides in considering the conduct of mere strangers, may not be so applicable to this case. It is testified by William Wyman that it was understood between the parties that as the defendant was to have the title, and consequently the power to sell, he would not do so without first apprizing Nehemiah. This duty would undoubtedly be implied by law if the bill states the contract truly. But in considering whether the defendant would be likely to make the agreement stated in the bill, it should be remembered that it gave him the absolute control over the property, which he probably anticipated he could exert, if it should become necessary for his own protection.

The most material circumstance, in my judgment, in opposition to the testimony of the plaintiff's witnesses, is the lapse of time. Apart from all technical considerations drawn from statutes of limitation, or rules I of law framed for the repose of titles, the lapse of time predisposes every judicial mind to look with disfavor on claims, and on evidence in support of them. I am sensible of having approached this case with such a predisposition. Yet, except when some rule of positive law interposes, or the principles of equity concerning acquiescence afford a bar to a claim, it is necessary to examine carefully the reasons for the delay, and the circumstances under which it has occurred. 745 I shall have occasion to state some of my views on this subject in speaking hereafter of the statute of limitations. But I may say here, that the witnesses themselves declare that Nehemiah Wyman removed in 1835 to a distant state; that he returned but once to this part of the country, in 1840, four years before the land was sold; that he had no knowledge of the sale of the land till 1851; that though the witness William Wyman knew of the sale of the land soon after it was made, when he spoke to the defendant concerning his brother's rights, the defendant informed him the right was barred by the statute of limitations, and he credited the assertion. These statements are not improbable in themselves, and they go far to explain the silence of these persons. Though I cannot say it is perfectly satisfactory, it is so far sufficient that in considering their evidence upon the main points of the case, I do not think much is to be detracted from its weight, by reason of Nehemiah's having omitted to make earlier claim.

It is further urged that William Wyman, who acted as scrivener in this transaction, was well acquainted with the forms of such business, and that Nehemiah Wyman having executed mortgages previously, must also be supposed to have known that a written defeasance ought to be given, and it is asked, why was it omitted if a mortgage was really intended. The defendant put this same question to Nehemiah Wyman on his cross-examination. He was asked “If there was understood between you and said Babcock any defeasance to the deed of November 20, 1828, why was not said defeasance reduced to writing.” His answer is: “It was a confidential transaction between three brothers, and we all well understood the same, and for what intent the deed was made. The deed was intended and understood by us three, to operate as a mortgage, but being a transaction between brothers, we did not think it necessary to be so particular in setting forth the rights of the respective parties, never anticipating that there would be any difficulty in a settlement between Mr. Babcock and myself.” There is a fact in the case which strongly corroborates this statement, that a defeasance was omitted upon a mutual confidence, then subsisting between these parties. In April, 1826, Nehemiah Wyman executed a mortgage to the defendant to secure a negotiable note for twelve hundred dollars, payable in one year from its date, with interest. The real object was to secure future advances. These papers having been prepared by Mr. Tufts, a lawyer, he drew up a memorandum, declaring the object of the mortgage, and the defendant signed it, yet it appears never to have been delivered to the mortgagor and was found by William Wyman, who produced it, in the possession of the defendant.

In respect to the value of the land at the time of the conveyance, I do not perceive how I can avoid the conclusion, that it exceeded considerably, the consideration alleged by the defendant to have been paid for it. It had been purchased by Nehemiah, at an auction sale of his deceased father's estate, eight years before, for  , and the fences had been in part built anew. Three years previous, (in 1825,) one acre had been sold to Foster for $600. There is some evidence tending to show, that in 1830, the defendant, with the concurrence of William Wyman, offered to sell the land at $200 per acre; but this was when real property was much depressed in value. Both the plaintiff's witnesses testify that they believed the land of much greater value than the consideration mentioned in the deed. This is matter of opinion, but the defendant produces no witness who expresses a different opinion.

, and the fences had been in part built anew. Three years previous, (in 1825,) one acre had been sold to Foster for $600. There is some evidence tending to show, that in 1830, the defendant, with the concurrence of William Wyman, offered to sell the land at $200 per acre; but this was when real property was much depressed in value. Both the plaintiff's witnesses testify that they believed the land of much greater value than the consideration mentioned in the deed. This is matter of opinion, but the defendant produces no witness who expresses a different opinion.

I have stated, in some detail, the views I have taken of the principal points involved in this question of fact, because I think it due to the parties that I should do so. The results at which I have arrived are, that the account given of the transaction in the answer, is so unsatisfactory, and the positive evidence of two competent witnesses is so far corroborated by circumstances, that I consider the answer overborne by their testimony, and that the allegation of the bill, that the conveyance of November, 1828, was made only as security, and not as an absolute sale of the land, is made out in proof.

The next question is, whether this oral evidence is admissible for the purpose of showing that a deed absolute on its face, was intended as a mortgage, and that the defeasance was omitted from mutual confidence between the parties. This question has been elaborately and learnedly argued by the defendant's counsel. I consider it to be settled by authority, which in this court is decisive. In Taylor v. Luther [Case No. 13,796] the precise question arose. It was a bill to have a deed absolute on its face, declared to be a mortgage by force of a defeasance, which the bill alleges was by parol. The defendant denied that the conveyance was intended as a mortgage, and set up the statute of frauds. The complainant relied by the bill, solely on a parol agreement for-his right of redemption. Mr. Justice Story, after stating the rule, laid down by numerous authorities, that parol evidence is admissible to show that an absolute deed was intended as a” mortgage, and that the defeasance had been omitted, or destroyed, by fraud or mistake, adds: “It is the same, if omitted by design, upon mutual confidence between the parties,”—and he proceeds to state the reasons, and made a decree resting on parol evidence only. In Jenkins v. Eldredge [Id. 7,266], he reaffirmed the same position. The cases of Conway v. Alexandra 7 Cranch [11 U. S.] 238; 746Spriggs v. Bank of Mount Pleasant, 11 Pet. [39 U. S.] 201; Morris v. Nixon, 1 How. [42 U. S.] 126; and Russell v. Southard, 12 How. [53 U. S.] 139, fully support the doctrine upon which Mr. Justice Story decided Taylor v. Luther [supra]. In Russell v. Southard this question was elaborately argued, and the authorities were examined, and carefully considered by the supreme court. It is true a memorandum in writing was given in that case; but the memorandum disproved the allegation that the conveyance was a mortgage; parol evidence was admitted to control that memorandum, and to prove that it did not show the actual transaction; and a decree was made, declaring the conveyance to be a mortgage, by force of the parol evidence only. It was there stated to be the doctrine of the court “that when it is alleged and proved that a loan on security was intended, and the defendant sets up the loan as a payment of purchase-money, and the conveyance as a sale, both fraud and device in the consideration are sufficiently averred and proved to require a court of equity to bold the transaction to be a mortgage.” My opinion is, that the statute of frauds does not afford a bar to the admission of the parol evidence in this case.

The remaining questions respect the effect of the statute of limitations, and the foreclosure of the mortgage. The statutes of Massachusetts concerning the foreclosure of mortgages can have no direct operation on the case, because they include only legal mortgages; and no indirect effect by affording an analogy to be followed by a court of equity, if for no other reason, because there was no entry by this mortgage after condition broken, and no entry before, and holding after condition broken, with notice of an intention to foreclose, as is required by the law of this state. The case must be considered, therefore, under the rules which equity has prescribed, concerning the duration of an equity of redemption, and also for limiting the other peculiar rights which belong to the complainant. In Hughes v. Edwards, 9 Wheat [22 U. S.] 497, the rule is thus laid down: “In the case of a mortgagor coming to redeem, the courts of equity have, by analogy to the statute of limitations, which takes away the right of entry of the plaintiff after twenty years adverse possession, fixed upon that as the period after forfeiture and possession taken by the mortgagee, no interest having been paid in the mean time, and no circumstances to account for the neglect appearing, beyond which a right of redemption shall not be favored.” And this rule is amply supported by authority. 4 Kent, Comm. 291, and cases there referred to; Dexter v. Arnold [Case No. 3,859], and cases in the notes. This bar is founded on the presumption of a release by the mortgagor, drawn from his neglect to redeem after forfeiture. It is plain that it can have no application to a case where there has been no breach of condition, and nothing which can be attributed to the mortgagor as neglect.

In the case at bar no time was fixed by the parties, after which the condition could be considered broken, and the right to have the foreclosure by lapse of time begin. The agreement charged and proved is, that the mortgagee was to take possession, apply the rents and profits to keep down the interest, and the residue towards the payment of the principal, and that the mortgagor might redeem at any time. Whether upon an application by the mortgagees to a court of equity upon a bill to foreclose the mortgage, this right to redeem at any time, would not have been construed to mean at any reasonable time, and whether after the lapse of such time, the court would not have lent Its aid to foreclose, need not be determined, though I should apprehend there could be little doubt respecting it. But mere lapse of time, unaided by any request to the mortgagor to redeem, or any notice to him that the mortgagee considered him in default, and was holding to foreclose, cannot, in this case, bar the right. I should have no difficulty in so holding upon principle, but I consider the position supported by authority. White v. Pigion, Toth. 135; Palmer v. Jackson, 5 Brown, Pari. Cas. 281; Orde v. Heming, 1 Vern. 418; Yates v. Hambly, 2 Atk. 359. It was argued that these authorities are not applicable because, in this case, the debts secured by the mortgage were all payable, and an action might have been brought at any time against the mortgagor and he forced to pay, and that the right thus to sue him personally, is not even alleged by the bill to have been waived or suspended. This does not make a distinction satisfactory to my mind. Every mortgagor who signs a bond or promissory note, and secures its payment by a mortgage, is liable to an action upon it in personam, the moment it becomes payable; and so far as the process of the law may be effectual for that purpose, may be forced at once to pay the debt, and thus to redeem the land. But all this stands with an ordinary equity of redemption. Why not with this equity? On the other hand, the personal claim of the mortgagee may be barred by the statute of limitations, for six years, while his right as mortgagee remains good fourteen years longer. I think the correct doctrine was stated in Coggswell v. Warren [Case No. 2,958].

There is another point of view in which I think it is not possible to sustain the bar, and which I consider presents the case in its true light. The mortgagee entered in 1828, and he sold the land in 1844, to bona fide purchasers without notice, who undoubtedly acquired an absolute title to the lands. In other words, the mortgagor's, right of redemption was effectually destroyed by the mortgagee, when he had held only sixteen years, and while that right of redemption was, consequently, still subsisting. This act of the 747mortgagee was done without notice to the mortgagor, as is admitted in the answer. Such a sale was a constructive fraud on the rights of the mortgagor, and turned his right to redeem into a claim against the mortgagee personally, for an account of the value of the land, and of the rents and profits. Now the limitation of such claims in equity is, six years after the discovery of the fraud by the aggrieved party. Here the bill charges a studious concealment of the sale by this mortgagee, and that the mortgagor had no notice of the sale, and that he was in a distant state. The answer admits, that the defendant dealt with the land as his own; and though it denies intentional concealment, says, no notice of the sale was given to the mortgagee. The proof shows that the mortgagee first discovered the sale in 1831, and accounts reasonably for his ignorance, and for the discovery. It may be, that if the possession of the mortgagee and those claiming under him, and the neglect of the mortgagor was such as to bar a claim to redeem, it would also bar a claim for an account for a constructive fraud, in destroying his right of redemption. But as the circumstances of this case would not, in my judgment, allow the mortgagee to set up his possession, if it had lasted more than twenty years, as a bar to a claim for redemption, and as six years have not elapsed since the discovery of the claim for an account on the ground of a constructive fraud, I do not consider the statute of limitations, or any analogy drawn from it by courts of equity, affords a bar to this bill.

My attention has been attracted to a point not insisted on at the bar, concerning the right of the complainant to maintain this bill. If it were not for the relation subsisting between the parties to the sale of the right in question, there might be some difficulty in maintaining it Though the doctrine held by Mr. Justice Story on this subject would seem to be broad enough to cover such a purchase by a mere stranger. Gordon v. Lewis [Case No. 5,613]; Baker v. Whiting [Id. 787]. But the ease of father and son has always afforded an exception to the general rules concerning champerty, and there seems to be nothing in the nature of the interest sold, which would on any other ground, preclude a court of equity from recognizing the title of the assignee. 2 Story, Eq. Jur. § 1049.

Let a decree be entered declaring the conveyance of November, 1828, to have been a mortgage to secure the debts, the amount whereof is named in the consideration of the deed, and that at the times of the sales of the land by the defendant, the complainant's assignor had right to redeem the same,—that the absolute sales and conveyances of the land to bona fide purchasers for valuable considerations, without notice, was a constructive fraud upon the rights of the complainant's assignor,—that thereupon he became entitled, as against the defendant personally, to an account of the then value of the land, and of the rents and profits, and (after deducting the amount due to the defendant for principal and interest) to the payment of the balance, and that the complainant, as assignee, has succeeded to those rights; and let the cause be referred to a master to take the necessary accounts.

[On appeal to the supreme court, the above decree was affirmed. 19 How. (60 U. S.) 289.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.

, the defendant, being the executor and trustee under the will of Francis Wyman, in that right holding this mortgage; and the second being a mortgage from Nehemiah to the defendant, nominally to secure the sum of $1,200 and interest, but really to secure the repayment of such sums as might be advanced by the defendant to Nehemiah; and that on this last-mentioned mortgage there was then due, for such advances, the sum of four hundred dollars. The bill further states, that at the same time, Nehemiah also owed to the defendant, personally, eight dollars

, the defendant, being the executor and trustee under the will of Francis Wyman, in that right holding this mortgage; and the second being a mortgage from Nehemiah to the defendant, nominally to secure the sum of $1,200 and interest, but really to secure the repayment of such sums as might be advanced by the defendant to Nehemiah; and that on this last-mentioned mortgage there was then due, for such advances, the sum of four hundred dollars. The bill further states, that at the same time, Nehemiah also owed to the defendant, personally, eight dollars  , and to him, as agent for the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman, senior, the sum of one hundred and thirty-six dollars

, and to him, as agent for the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman, senior, the sum of one hundred and thirty-six dollars  ; that Nehemiah was much embarrassed in his affairs, and at the pressing solicitation of the defendant, who was his brother-in-law, and of William Wyman, his brother, he consented to make a deed of the said land, excepting the Foster acre, to the defendant, absolute 742in form, but intended to stand as security for what Nehemiah thus owed; that the conveyance was made for that purpose only, and the defendant went into possession; that none of the notes held by the defendant were surrendered or cancelled, the same being retained because the land was taken as security only; that the defendant was to have the management of the land and receive the rents and profits, and apply them towards the accruing interest; and if there should be any excess, towards the principal, and that Nehemiah was to have the right to redeem at any time when he should be able to do so. The bill further states, that in 1844 the defendant, without any notice to Nehemiah, of his intention to sell, or to the purchasers, of the nature of his title, sold the land by an absolute title, to bona fide purchasers, without notice; and it prays for an account of the rents and profits while held by the defendant, and of the value of the land when sold, and that after deducting the amount for which the land stood as security, the residue may be paid to the complainant, who alleges himself to be the assignee, by deed, for a valuable consideration, of all Nehemiah's equity in the premises.

; that Nehemiah was much embarrassed in his affairs, and at the pressing solicitation of the defendant, who was his brother-in-law, and of William Wyman, his brother, he consented to make a deed of the said land, excepting the Foster acre, to the defendant, absolute 742in form, but intended to stand as security for what Nehemiah thus owed; that the conveyance was made for that purpose only, and the defendant went into possession; that none of the notes held by the defendant were surrendered or cancelled, the same being retained because the land was taken as security only; that the defendant was to have the management of the land and receive the rents and profits, and apply them towards the accruing interest; and if there should be any excess, towards the principal, and that Nehemiah was to have the right to redeem at any time when he should be able to do so. The bill further states, that in 1844 the defendant, without any notice to Nehemiah, of his intention to sell, or to the purchasers, of the nature of his title, sold the land by an absolute title, to bona fide purchasers, without notice; and it prays for an account of the rents and profits while held by the defendant, and of the value of the land when sold, and that after deducting the amount for which the land stood as security, the residue may be paid to the complainant, who alleges himself to be the assignee, by deed, for a valuable consideration, of all Nehemiah's equity in the premises. owed to this defendant, and fifty dollars owed to him as agent for the heirs;” and there is no doubt whatever how the amount expressed in the deed was arrived at, and that it was by a careful computation of the principal and interest due, at the date of the deed, to the defendant in his own right as executor and trustee, for the children of Francis Wyman, and as agent of the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman. If the above statement in the answer is correct, it is difficult to perceive how the debt due to the defendant as executor and trustee, for which the land was already mortgaged, formed any part of the consideration of this deed, or why it was said by the deed to do so; and still less why the amount due to the defendant as agent for the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman, senior, was included in the consideration; for according to the answer, there was no agreement at all concerning the application of the land, or its proceeds, to that debt.

owed to this defendant, and fifty dollars owed to him as agent for the heirs;” and there is no doubt whatever how the amount expressed in the deed was arrived at, and that it was by a careful computation of the principal and interest due, at the date of the deed, to the defendant in his own right as executor and trustee, for the children of Francis Wyman, and as agent of the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman. If the above statement in the answer is correct, it is difficult to perceive how the debt due to the defendant as executor and trustee, for which the land was already mortgaged, formed any part of the consideration of this deed, or why it was said by the deed to do so; and still less why the amount due to the defendant as agent for the heirs of Nehemiah Wyman, senior, was included in the consideration; for according to the answer, there was no agreement at all concerning the application of the land, or its proceeds, to that debt. is dated November 7th, 1828; and two others, one for eight dollars

is dated November 7th, 1828; and two others, one for eight dollars  , and the other for fifty dollars, are dated. November 11, 1828, and all bear interest. It is testified by William Wyman, and there is no evidence to the contrary, and it is in itself probable, that this conveyance was under negotiation for some time. The deed bears date on the 20th of November, 1828. If it was intended it should stand as a security, there was reason for reducing the debts to the permanent form of notes bearing interest, which the defendant could retain, as he in fact did retain them; if it was intended to receive the deed in payment of these debts, it is not probable they would have been put into this form, pending the negotiation.

, and the other for fifty dollars, are dated. November 11, 1828, and all bear interest. It is testified by William Wyman, and there is no evidence to the contrary, and it is in itself probable, that this conveyance was under negotiation for some time. The deed bears date on the 20th of November, 1828. If it was intended it should stand as a security, there was reason for reducing the debts to the permanent form of notes bearing interest, which the defendant could retain, as he in fact did retain them; if it was intended to receive the deed in payment of these debts, it is not probable they would have been put into this form, pending the negotiation. , and the fences had been in part built anew. Three years previous, (in 1825,) one acre had been sold to Foster for $600. There is some evidence tending to show, that in 1830, the defendant, with the concurrence of William Wyman, offered to sell the land at $200 per acre; but this was when real property was much depressed in value. Both the plaintiff's witnesses testify that they believed the land of much greater value than the consideration mentioned in the deed. This is matter of opinion, but the defendant produces no witness who expresses a different opinion.

, and the fences had been in part built anew. Three years previous, (in 1825,) one acre had been sold to Foster for $600. There is some evidence tending to show, that in 1830, the defendant, with the concurrence of William Wyman, offered to sell the land at $200 per acre; but this was when real property was much depressed in value. Both the plaintiff's witnesses testify that they believed the land of much greater value than the consideration mentioned in the deed. This is matter of opinion, but the defendant produces no witness who expresses a different opinion.