shows the irregular curve upon the face of the clearing teeth, intended to cut or plane out the kerf, and which has that effect. 912 Defendants' saw, Exhibit “E,” Record, p. 32.

shows the irregular curve upon the face of the clearing teeth, intended to cut or plane out the kerf, and which has that effect. 912 Defendants' saw, Exhibit “E,” Record, p. 32.Case No. 17,500.

WHEELER et al. v. SIMPSON et al.

HOE et al. v. SAME.

[1 Ban. & A. 420;1 6 O. G. 435.]

Circuit Court, N. D. New York.

Sept., 1874.

INFRINGEMENT OF PATENTS—VALIDITY OF CLAIMS—LAWS.

1. A patent for a saw, claiming, in combination, clearing teeth hollowed out in front, so as to plane out the wood between the scores cut by the fleam teeth, is not infringed by a saw in which the wood is rasped out by clearing teeth, which are straight and perpendicular in front.

2. A claim for an effect or function, in the abstract, cannot be sustained; the means by which the effect is produced, or the function performed, must be specified.

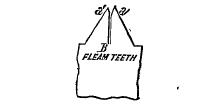

3. A saw having its fleam teeth of the usual triangular form, with intervals between them, operates by means of a construction so unlike that of a saw having its fleam teeth arranged in pairs, with only a perpendicular slit between them, that it is no infringement of a patent for the latter, although the effect may be the same.

[These were suits in equity, brought respectively by Elisha P. Wheeler and others and by Richard M. Hoe and others against Ambrose H. Simpson and others for alleged infringement of a patent.]

C. A. Durgin and Mr. Everett, for complainants.

C. B. Collier, for defendants.

911HUNT, Circuit Justice. The plaintiffs in the Wheeler suit, are the assignees of the patent for “improvement in saws,” known as reissue No. 4,096, dated August 9, 1870, the original of which was dated June 21, 1853, No. 9,807, and of which Joseph H. Tuttle was the original inventor.

No question is here made, of the regularity of the plaintiffs' title, or of the sufficiency of the reissued patent. The defendants plan themselves solely upon the ground, that they are not infringers of the patent described.

What is claimed as the invention of Joseph, H. Tuttle, under the reissue No. 4,096, is:

“(1) The saw herein described, having a series of alternate sets of fleam and curved planing teeth, located upon the same plate or blade, the sets of fleam teeth for scoring the sides of the kerf, and sets of curved planing teeth for removing the wood between the scores, when constructed and arranged to operate in the manner shown and described.

“(2) A saw, as above described, having a series of alternate sets, or pairs, of scoring and curved planing teeth, the sets or pairs of scoring set to opposite sides of the blades to score the wood on the opposite sides of the kerf, the sets, or pairs, of curved planing teeth set back to back, and projecting less than the scoring teeth, and, when thus constructed and arranged, act as gauges to control the depth that the scoring teeth may cut, substantially in the manner described and shown.”

Fleam teeth, set in opposite directions, are not claimed as an invention. These are used in all cross-cut saws.

Hooked or curved teeth are not claimed as a part of the invention. Such teeth were previously well known in saws, and were used in Clark's patent of 1849, referred to in the Tuttle specification. The use of scoring teeth and of planing teeth upon the same blade, is not claimed as an invention. This use was previously well known, and was a part of Rone's rejected application, in the plaintiffs' specification also referred to.

The position and use of these different teeth, in the “manner described in the specification,” is the plaintiffs' invention. What is the manner referred to?

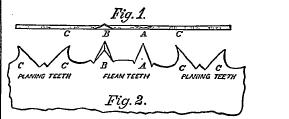

(1) The fleam teeth project beyond the cutting teeth and cut two straight scores, one on each side of the kerf. (2) The hooked teeth are set back to back, and, at such distance, that while the cut is made by one tooth, the back of the other regulates the depth of the cut, the teeth not cutting serving as guides to those that are cutting. By this means, cutting is done, in both directions, from end to end. (3) The hooked teeth are cut away under the front edge in the form of an irregular curve, so as to produce a uniform planing or cutting, instead of a rasping edge.

The combination of these teeth, in the manner thus described, is the invention patented.

Mr. Crawford, an expert, and the only one examined, says, that Mr. Turtle's advance, in this invention, was this: “In the construction and arrangement of the teeth, by which the wood scored by the scoring teeth on the opposite sides of the kerf was removed from the pathway of the saw, and also in constructing the clearing teeth, that they should act as gauges to determine the depth at which the scoring teeth should act in the wood.”

This definition differs from the patent in these respects: (a) The patent does not claim an advance in that the scoring teeth remove the wood from the pathway of the saw. (b) It omits the claim of the patent, that the wood is removed by a planing, instead of a rasping operation, (c) It omits the effect of the combined action of scoring teeth, and curved clearing teeth, set as described in the patent. The difference is illustrated by the evidence of complainants' expert in a former case, read on the hearing of this case: “(7) Do you not consider that it is of the essence of the invention of Joseph H. Tuttle, as described in reissued patent 4,096, that the clearing teeth should have this planing, in contradistinction of the scraping action? Answer. That, I believe to be one of the essential features of the invention of Joseph H. Tuttle, as recited in the said reissue of letters patent. (9) You do not find in Larimun's patent, or in defendants' patent (Ex. p.), any teeth having the planing action, or that could be called planing teeth, do you? Answer. I do not; as the teeth denominated clearing teeth would come under what I denominate as clearing teeth having a scraping instead of a planing action.”

On the cross examination of the expert Crawford, the following occurs: “(4) Cross question. What is the difference in the mode of clearing in the original letters patent here and in Exhibit E, defendants' patent, if any? Answer. All the difference I can define is, that in Exhibits A and B, the wood in the kerf is planed out, while that in Exhibit E is scraped out.”

The difference in the drawing, annexed to and forming a part of the several patents, shows that the machines are designed to produce the effect, in one, of planing out the kerf, and in the other, of rasping it out. (Plaintiff's Patent, Record, p. 18.)

This drawing  shows the irregular curve upon the face of the clearing teeth, intended to cut or plane out the kerf, and which has that effect. 912 Defendants' saw, Exhibit “E,” Record, p. 32.

shows the irregular curve upon the face of the clearing teeth, intended to cut or plane out the kerf, and which has that effect. 912 Defendants' saw, Exhibit “E,” Record, p. 32.

The drawing, forming a part of the specification of the defendants' patent, shows no teeth having a curved or cutting edge, but they are straight in their form and rasping in their operation. The one set of teeth cuts or planes out the wood, the other rasps or scrapes it out. In its want of plaintiffs' combination, and in the non-use of a planing operation, defendants' machine is essentially different from the plaintiffs' patent, and the proof of infringement fails. There is, I conceive, a coincidence in this, that the clearing teeth in each machine operate as a gauge or guide, to determine the depth of the cut of the scoring teeth. But, I think, an action for an infringement cannot be maintained upon this ground.

It is too well settled, to need the citation of authorities, that a claim for an effect or a function, in the abstract, is not patentable. The mode and machinery by which the effect is produced must be set forth. The party cannot, for example, sustain a patent for determining the depth of the cut of cutting teeth, in the abstract, or by any and all means that may be suggested. He must, as in the present case has been done, specify how he determines the depth of the cut. Thus, the patent says, that the teeth are cut away under the front or cutting edge, in the form of an irregular curve standing at an angle of forty five degrees, placed back to back, and curved in opposite directions at a suitable distance from each other, and “when thus constructed and arranged to act as gauges to control the depth that the scoring teeth may cut.”

The teeth in the defendants' saw, by which a like effect is produced, are not “thus constructed and arranged.” The construction and arrangement differ in these essential particulars: The teeth in the plaintiffs' patent are cut in the form of an irregular curve; those in the defendants' patent are straight. The plaintiffs' teeth are cut away under their cutting edges; the defendants' are not. The plaintiffs' are necessarily required to be at a considerable distance from each other, or the effect fails. No such necessity exists, as to the location of the teeth, in defendants' patent. In my judgment, there is no infringement proved.

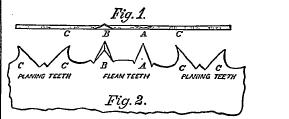

In the Hoe case, the plaintiffs' patent, No. 37,835, is for “the employment of alternate clearing teeth dd, the ends of which are concave or notched so as to form sharp or pointed corners, in combination with the triangular pairs of cutting teeth aá, arranged on a single blade, substantially as and for the purposes herein set forth.”

The claim of the patent is for the use of certain described cutting teeth, in combination with the clearing teeth, as described.

The cutting teeth are in this form  as described in the plaintiffs' patent

as described in the plaintiffs' patent

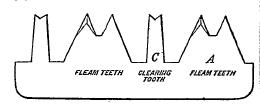

The cutting teeth of the defendants' saws are in this form,  and are different, in all their essential particulars, from those described in the plaintiffs' patent. While the same result may be produced, to wit, that the fleam teeth cut down the sides, and the clearing teeth cut out the wood, the result is not produced by teeth of the same form or character.

and are different, in all their essential particulars, from those described in the plaintiffs' patent. While the same result may be produced, to wit, that the fleam teeth cut down the sides, and the clearing teeth cut out the wood, the result is not produced by teeth of the same form or character.

The expert Crawford says: “The operations and functions of the teeth in the two exhibits are the same.” He also says that, “the combinations and arrangements of the teeth are the same, all the difference being, that in plaintiffs' patent the scoring teeth, at their cutting points, are nearer together than in Exhibit E.”

I understand the plaintiffs' patent to be limited to the use of notched clearing teeth, in combination with the particular triangular pairs of cutting teeth, which he describes. Thus, in his prior patent of January 6, 1863, he says: “I do not claim, broadly, the use of alternate pairs of cutting teeth with intermediate plane teeth, as I am aware that such, with the points situated at a considerable distance apart, have been used before; but, what I claim as my invention is the use of alternate triangular pairs of cutting teeth aa, separated individually by the narrow slit b, and with their points resting closely together, in combination,” etc.

The patent sued on, purports only to be an improvement upon the one of January 6, 1863, and, in my judgment, it is limited to a combination of cutting teeth, with the particular form of fleam teeth described in the patent of March 3, 1863. Although the operation and function of the teeth in the defendants' patent may be the same, they are produced by means of instruments quite different in their construction. I cannot agree with the statement, that the construction 913and arrangement of the teeth, in the two patents, are the same. In the January patent, the cutting teeth are thus described: “I make each pair of the cutting teeth aa, combined in the usual triangular pointed form of a single ordinary tooth, but a little larger, to give sufficient strength, and with a narrow central slit or opening b, between them, extending from point to base, as represented. The points of the teeth are thus situated closely together, nearly opposite each other laterally.” The same form is preserved and set forth in the patent sued on. The cutting teeth, used in the defendants' saw, possess none of these peculiarities. They are the ordinary cutting teeth, which have been in use for ages. There is no infringement proved. In each case, the bills must be dismissed with costs.

1 [Reported by Hubert A. Banning, Esq., and Henry Arden, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.