Case No. 17,324.

WEBB et al. v. QUINTARD.

[9 Blatchf. 352; 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 276; 1 O. G. 525; Hem. Pat. Inv. 708.]1

Circuit Court, S. D. New York.

Jan. 24, 1872.

PATENTS—ANTICIPATION—FOREIGN PUBLICATIONS—DATE OF INVENTION—REDUCTION TO PRACTICE—SHIP ARMOR.

1. The letters patent granted to Charles W. S. Heaton, April 14th, 1863, for an “improved defensive armor for ships and other batteries,” are void, for want of novelty.

2. In 1861, a description and drawings were published in a printed publication, in England. From those, the United States, in 1863, caused to be constructed and placed on a vessel, armor like that claimed in the patent of Heaton, one of such drawings being practically the same thing as the armor placed on such vessel. Heaton conceived the idea of his armor in 1856. In 1858, he experimented, by firing a pistol at small pieces of wood and iron. He made no experiments from the fore part of 1859 till the latter part of 1861, when he began to make a model of a war vessel, which he completed early in 1862. The first trial he made with real armor was in March, 1863. Held, that Heaton did not make his invention before the date of the English publication.

3. A printed publication is, by the 6th, 7th, and 15th sections of the act of July 4, 1836 6 Stat. 119, 123), put on the same footing with a patent taken out at the time of the publication; and, regarding the English publication as a patent, it was not unjustly obtained for that which had before been invented by Heaton, who was using reasonable diligence in adapting and perfecting it.

4. Heaton did not make his invention until he made his model, and he did not begin to make that until after the English publication had been made.

[Cited in Lamson v. Martin, 159 Mass. 565, 35 N. E. 81.]

5. A previous conception of the possibility of accomplishing what the English publication makes known, was not enough. There must have been a reduction of the idea to practice, and an embodiment of it in some distinct form.

2 [Final hearing on pleadings and proofs.

[Suit brought (by William H. Webb and Charles W. S. Heaton against George W. Quintard) on letters patent for an “improved defensive armor for ships and other batteries,” granted to complainant Charles W. S. Heaton, April 14, 1863.

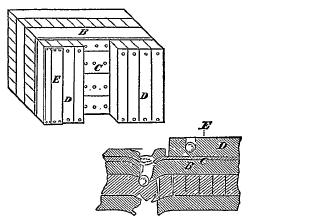

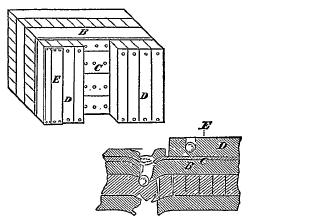

[The nature of the invention is set forth in the opinion, and will be readily understood by reference to the accompanying engraving, in which B represents the ordinary outer planking of a ship; C, metallic armor; D, an outer layer of timber; and E, a thin exterior sheathing of iron.

Charles F. Blake and. Samuel D. Cozzens, for plaintiffs.

Edward N. Dickerson, for defendant.

BLATCHFORD, District Judge. This suit is brought on letters patent granted to the plaintiff Heaton, April 14th, 1863, for an “improved defensive armor for ships and other batteries.” The specification states, that the longitudinal outer timbers of the vessel form the backing to the armor, that the armor plates are laid against the backing in the usual way, and that the armor plates are covered with an outer layer of timbers, to deaden and to gradually resist the penetrating force in its passage to the armor plates. It then says: “In this heavy buoyant surface lies the gist of my inversion or discovery. My invention consists, not in the introduction of wood, rubber, or any other like yielding substance, behind the metal armor, but in the discovery that a timber or other yielding surface, will deaden or resist the power of a cannon ball, when such wood or other surface is backed by the metal armor, which usually is on the surface, and when such metal armor is backed by sufficient wood or other backing to hold it rigidly in its normal position. My system of armor for vessels or forts does not contemplate stopping the ball at the immediate surface; but the metal, or armor proper, is placed at an intermediate point, so that, by the time the shot has reached it, its momentum is so greatly reduced, that it is arrested without serious injury, either from starting the bolts or fracturing the metal armor. The object of my system of armor is to render a war vessel or other structure shot-proof with a less amount of iron armor than is now used with that end in view. By using less metal and more timber, I increase, instead of decreasing, the buoyancy of a ship, and, at the same time, greatly increase the resisting effect of the armor plating. Another object which I have in view is, to obviate the tendency to break the bolts or fastenings of the plating, when it is struck by a 522ball.” The specification then illustrates the operation of the invention, in connection with drawings. It states that the patentee, in practice, simply overlays the iron armor of an ordinarily constructed vessel (which iron armor is backed up by sufficient backing to rigidly support the plates) with an outer layer of timber, which timber is only bolted on sufficiently strong to hold it to its place; and that his invention also consists in plating or thinly sheathing this timber, on its outer or exposed surface, not however to stop shot, but to prevent a raking shot from tearing the timber, and also to prevent the wood from being too readily set on fire, as such sheathing would exclude the air and so retard combustion. The claim of the patent is: “The employment of wood, or its equivalent, when used in the manner and for the purpose substantially as described.” The application for the patent was filed on the 28th of March, 1863.

In 1863, the government of the United States caused to be constructed for itself a vessel of war called the Onondaga. The vessel was built by the defendant, under a contract with the government, as a vessel with iron armor. During the progress of her construction, wooden armor on the outside of the main iron armor, and a thin plating of iron on the outside of such wooden armor, were put upon the vessel, by the order of the navy department, given in March, 1863. The wooden armor and the iron plating were put on and completed in June and July, 1863. Such wooden armor and iron plating were applied in consequence of a description and drawings published at London in 1861, at pages 8 to 17, and plate 2, of a volume entitled, “Transactions of the Institution of Naval Architects, Volume 2,” being a paper “On the construction of iron vessels of war iron-cased,” by J. D. Aguilar Samuda, Esq., and were made in accordance with such description and drawings. The vessel, when completed, passed into the ownership, possession and service of the government. On the 2d of March, 1867, an act was passed by congress (14 Stat. 543), authorizing and directing the secretary of the navy to deliver the vessel to the defendant for his own use and behoof, on the payment by him to the treasury of the United States of the sum of $759,673. He paid the money and received the vessel, and, in the spring of 1867, sold her to the French government, and delivered her at that time to such government, on such sale, in the city of New York. When so received and when so delivered, she had upon her the said wooden armor and iron plating. It is for this sale, as an infringement of the patent, that this suit is brought. The patentee, in his testimony in the case, admits that one of said drawings in said volume is practically the same thing as the armor of the Onondaga.

To counteract the force of this state of facts, it is attempted to carry back the invention of Heaton to a date anterior to 1861, but, I think, without success. The patentee testifies, that, while in England, in 1856, he saw an iron-clad gun-boat, and the idea occurred to him that the wood ought to be outside of the iron armor; that, within a week from that time, he wrote to the British admiralty, suggesting that a defence be made consisting of wood outside of iron, and asking for and or authority to experiment to that end; that, three or four months afterwards, he received a reply refusing such authority; that, in September or October, 1858, while in the United States, he fired a revolver at the wooden head of a nail keg, fastened by a wire to the sheet iron top of the perpendicular lever of a railroad switch, and hit the wood obliquely, and concluded that an oblique shot would damage the side of a ship more than a shot striking it squarely would; that, a few days afterwards, he fastened a piece of plank between a thin piece of sheet iron and a thick piece of sheet iron, and laid the article down on a railroad tie, with the thin iron piece uppermost, and fired at it with a revolver straight down, and also obliquely, and found that the thick iron under the plank was not affected by the shots, and that the thin iron prevented the oblique shots from damaging the plank; that he made no experiments from the forepart of 1859 till the latter part of 1861; that, at the latter date, he began to make a model of a war vessel, to illustrate his new system of armor; that, early in 1862, about the time the model was done, he wrote to the secretary of war, asking to have the model examined; that the first trial he made with real armor on his plan, by firing at it with cannon, was made in New York in March, 1863; and that a like trial was made by him at Washington City, about the same time. On these facts, it is contended, for the plaintiffs, that Heaton completed in 1856 the invention of putting wood outside of iron for armor, and that he completed in the fall of 1858 the invention of the wood outside of the iron, and the thin iron outside of the wood.

The 6th section of the act of July 4, 1836 (5 Stat. 119), provides for the granting of a patent to a person for an invention “not known or used by others before” his discovery or invention thereof. The 7th section provides, that there shall be an examination of the alleged new invention, and that if, on the examination, it shall not appear “that the same had been invented or discovered by any other person in this country, prior to the alleged invention or discovery thereof by the applicant, or that it had been patented or described in any printed publication in this or any foreign country, or had been in public use or on sale, with the applicant's consent or allowance, prior to the application, if the commissioner shall deem it to be sufficiently useful and important, it shall be his duty to issue a patent therefor; but whenever, on such examination, it shall appear to the commissioner 523that the applicant was not the original and first inventor or discoverer thereof, or that any part of that which is claimed as new had before been invented or discovered, or patented, or described in any printed publication, in this or any foreign country, as aforesaid, or that the description is defective and insufficient; he shall notify the applicant thereof, giving him briefly such information and references as may be useful in judging of the propriety of renewing his application, or of altering his specification to embrace only that part of the invention or discovery which is new.” The 15th section provides, that it shall be a defence to an action at law on a patent, “that the patentee was not the original and first inventor or discoverer of the thing patented, or of a substantial and material part thereof claimed as new, or that it had been described in some public work anterior to the supposed discovery thereof by the patentee or that he had surreptitiously or unjustly obtained the patent for that which was in fact invented and discovered by another, who was using reasonable diligence in adapting and perfecting the same; provided, however, that, whenever it shall satisfactorily appear that the patentee, at the time of making his application for the patent, believed himself to be the first inventor or discoverer of the thing patented, the same shall not be held to be void on account of the invention or discovery, or any part thereof, having been before known or used in any foreign country, it not appearing that the same, or any substantial part thereof, had before been patented or described in any printed publication.” These provisions' of the 6th, 7th and 15th sections of the act of 1836 have been, in substance, re-enacted in the act of July 8, 1870 (16 Stat. 198).

Under these provisions of law, if the publication in the English work preceded the discovery by Heaton, the defence to the suit is made out. Under the law, the publication in the English work is put on the same footing with a patent taken out at the time of the publication. The sole question, therefore, is, whether Heaton made his invention before the date of the English publication. The occurring of the idea to him, in England, in 1856, and his letter to the British admiralty, certainly, cannot be regarded as a making of the invention. Nor can his pistol practice in 1858 be so regarded. The first attempt he made to embody his ideas in a practical form, by constructing a model, was in the latter part of 1861, the model having been finished early in 1862. This was all of it, according to the evidence, after the publication had been made in England, from which the Onondaga was armored as she was. If the English publication were an American patent, could it be said, in defence to an action on it, that it was unjustly obtained, for that which had in fact before been invented by Heaton, who was using reasonable diligence in adapting and perfecting it? Heaton may have used reasonable diligence in developing his ideas towards making an invention. But that is not the point. To give him a precedence over the English publication, he must have first made the invention, and then have been using reasonable diligence in adapting and perfecting the invention so made. When did he make the invention? Not until he made the model, which, according to the evidence, he did not begin to make until after the English publication had been made. The articles at which he fired with a pistol cannot be regarded as an embodiment of the invention, so as to destroy the rights of the defendant in respect of a vessel actually armored in accordance with what was published in England in 1861. Colt v. Massachusetts Arms Co. [Case No. 3,030]. Looking at the English publication as a patent issued, which is the proper view in respect to this case, it cannot be defeated by showing that Heaton previously conceived the possibility of accomplishing what the publication makes known so satisfactorily that it has been followed in armoring the Onondaga. To constitute Heaton a prior inventor, he must have proceeded so far as to have before reduced his idea to practice, and embodied it in some distinct form. Parkhurst v. Kinsman [Id. 10,757]. In order to prevent the defendant from having the benefit of the English publication, it is necessary that Heaton should have previously discovered the thing, and reduced it to actual practice. Cox v. Griggs [Id. 3,302]. The pistol practice of Heaton was not a reduction of his ideas to practice, or an embodiment of them in a distinct form, within the good sense of these rules, so as to constitute an invention on his part, within the meaning of the statute.

The bill must be dismissed, with costs.

[For another case involving this patent, see Heaton v. Quintard, Case No. 6,311.]

1 [Reported by Hon. Samuel Blatchford, District Judge, and by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here compiled and reprinted by permission. The syllabus and opinion are from 9 Blatchf. 352, and the statement is from 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 276. Merw. Pat. Inv. 708, contains only in partial report.]

2 [From 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 276.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.