74

Case No. 17,100.

WALLACE et al. v. HOLMES et al.

[9 Blatchf. 65; 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 37; 1 O. G. 117.]1

Circuit Court, D. Connecticut.

Sept 19, 1871.

PARTIES IN EQUITY—WAIVER—GUARDIANS—POWER TO SELL PERSONALTY—MASSACHUSETTS STATUTE—PATENTS—INFRINGEMENT—LAMPS.

1. Where, in a suit in equity, the want of parties is not set up or suggested in the answer, it cannot avail, on final hearing, unless the case is one in which the court cannot proceed to a decree between the parties before it, without prejudice to the rights of those who are proper to be made parties, but who are not brought into court.

2. In the absence of a restraining statute, a guardian of the person and estate of an infant, appointed by a court of probate, has, as incidental to his office and duties, the power to sell personal property of his ward.

3. The statute of Massachusetts (Gen. St. Mass. c. 109, § 22) providing that the courts therein named may authorize or require a guardian to sell personal property held by him as guardian, and invest the proceeds in real estate, or otherwise, does not take away the power of the guardian to sell such personal property without an order of the court, and to confer title thereto on the purchaser.

4. Where a structure consisting of several parts is patented as a combination, one who manufactures and sells some of the parts, they being useless without the residue, with the understanding and intent that such residue shall be supplied by another, and the whole go into use in its complete form, is liable as an infringer of the patent.

[Applied in Renwick v. Pond, Case No. 11,702. Distinguished in Saxe v. Hammond, Id. 12,411. Approved in Turrell v. Spaeth, Id. 14,267. Followed in Rumford Chemical Works v. Hecker, Id. 12,133. Distinguished in Buerk v. Imhaeuser, Id. 2,108; Morgan Envelope Co. v. Albany Perforated Wrapping-Paper Co., 152 U. S. 425, 14 Sup. Ct. 630; Maynard v. Pawling, 3 Fed. 713. Cited in New York Bung & Bushing Co. v. Hoffman, 9 Fed. 201. Followed in Travers v. Beyer, 26 Fed. 450. Cited in Harper v. Shoppell, Id. 521; Alabastine Co. v. Payne, 27 Fed. 560; Harper v. Shoppell, 28 Fed. 615; Syracuse Chilled-Plow Co. v. Robinson, 35 Fed. 503; Schneider v. Missouri Glass Co., 36 Fed. 584. Distinguished in Winne v. Bedell, 40 Fed. 465. Cited in Hobbie v. Jennison, Id. 890; Boyd v. Cherry, 50 Fed. 282. Distinguished in Robbins v. Columbus Watch Co., Id. 555. Cited in brief in Heaton Peninsular Button-Fastener Co. v. Dick, 55 Fed. 26.]

5. Letters patent were granted to Michael H. Collins, September 19th, 1865, for an “improvement in lamps.” The claim was to “the improved lamp, as not only constructed with its 75cone or deflector, F, and its chimney-rest, D, and chimney, arranged with respect to each other as described, but as having the said deflector provided with peripheral springs, or the same, or the slits, h, h, and the rest, D, made concavo-convex, and provided with an annular groove or lip at the bottom, for supporting the chimney, the whole being substantially as described or represented.” The specification described the main purpose of the invention to be, not only to keep the lower part of the glass chimney of the lamp cool, so that it might readily be removed by the hand, but also to support the chimney without the use of a spring catch, or other devices, such as are ordinarily used. The distinguishing feature of the invention claimed was the burner, with its chimney-rest, a deflector having peripheral springs, to sustain the chimney without the and of a catch or screw, and with air-passages operating, when in use, to keep the lower part of the chimney cool, and tending, by that means, and by the greater elevation of the flame, to prevent the lower portion of the burner and top of the reservoir from becoming unduly heated. The burner alone, or the burner attached to the reservoir, was useless, without a chimney; and a chimney was useless without a burner. The defendants made and sold burners substantially like the patented invention, but, although they used such burners with chimneys placed therein, to exhibit the burners to customers, they did not make or sell the chimneys. Held, that the claim of the patent was a claim to the burner in combination with the chimney.

6. The defendants must be regarded as active parties in the whole infringement, by making and selling the burner to be used with the chimney.

[Cited in Rumford Chemical Works v. Vice, Case No. 12,136; Bowker v. Dows, Id. 1,734. Approved in Schneider v. Pountney, 21 Fed. 403. Cited in Lane v. Park, 49 Fed. 458.]

2 [Final hearing on pleadings and proofs.

[Suit brought upon letters patent [No. 49,984], for an “improvement in lamps,” granted to Michael H. Collins, September 19, 1865, and assigned to complainants.

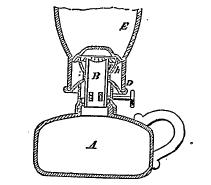

[The facts of the case and the claims of the patent are set forth in the opinion, and will be understood by reference to the accompanying drawing, in which A represents  the lamp, B the wick-tube, E the chimney, & the chimney-rest, and F the cone or deflector, provided around its upper edge with peripheral springs, or having the edge cut into radial slits, h, the function of which is to press against the glass of the chimney and hold it in place.]2

the lamp, B the wick-tube, E the chimney, & the chimney-rest, and F the cone or deflector, provided around its upper edge with peripheral springs, or having the edge cut into radial slits, h, the function of which is to press against the glass of the chimney and hold it in place.]2

3 [This was a suit in equity brought by Wallace & Sons and Phelps, Dodge & Co. against Holmes, Booth & Haydens for the alleged infringement of certain letters patent for an improvement in lamps, granted to Michael H. Collins, September 19, 1865. No defect in complainants' title appears to have been set up in the answer to the bill; but at the hearing defendants averred a lack of sole title in complainants, and made this one of the chief points of defense. From the record in the case it appears that on the 24th of September, 1867, Collins and his wife, the former as guardian for his minor daughter, conveyed the patent in suit to one Warren for a nominal consideration, the deed of assignment reciting an alleged previous assignment of the same to the wife and child, and that on the same day, and for the same consideration, Warren conveyed all his right, title, and interest in the patent to Collins. It further appears that on the 24th of December, 1867, doubt being entertained as to the legal efficacy of these conveyances, Collins, in his own behalf and as the guardian of his daughter, assigned the patent and the invention secured thereby to the complainants; and on the following day still another instrument was executed by Collins and his wife jointly, which recited a doubt as to whether any interest had ever passed to the wife, and assigning to the same parties all the interest that she ever may have acquired. It was urged, upon this state of facts, that the transactions to which Warren was a party were tainted with fraud as aiming to transfer a valuable property from the ward to the person holding the relation of guardian for a manifestly inadequate compensation, and therefore were illegal; and that the subsequent assignment of December 24 was not free from the same suspicion of fraudulent intent. Reference was also made to the General Statutes of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, in which state Collins and his daughter lived, which enacts as follows: “The probate courts in the several counties, and the supreme judicial court, on the application of a guardian, or any other person interested in the estate of a ward, after notice to all other persons interested therein, may authorize or require the guardian to sell and transfer any stock in the public funds or in any corporation, or any other personal estate or effects held by him as guardian, and invest the proceeds thereof and all other moneys in his hands in real estate, or in any other manner that shall be most for the interest of all concerned. Said courts may make such further order and give such directions as the case may require for managing, investing, and disposing of the estate and effects in the hands of a 76guardian.” Gen. St. Mass., c. 109, § 22. It was urged that this statute was intended primarily for the protection of the estates of wards by requiring judicial sanction for every transfer of property, personal as well as real, made in their behalf; and therefore, as it did not appear that Collins had obtained any order from the court authorizing the sale of his ward's interest in the patent in question, it could not be held that the interest once held by her had become vested in complainants by the instruments above recited. For these reasons it was contended that complainants did not hold the entire title in the patent; that Michael H. Collins, as guardian, should have been joined as parry plaintiff in the bill, and that by means of this not being done the suit could not be maintained.

[The other ground relied upon by the defense at the time of trial was non-infringement of the patent. The invention as patented is sufficiently described in the opinion rendered by the court. The claim of the patent is in these words: “I claim the improved lamp as not only constructed with its cone or deflector, F, and its chimney-rest D, and chimney, arranged with respect to each other as described, but as having the said deflector provided with peripheral springs, or the same and the slits, h, h, and the rest, D, made concavo-convex and provided with an annular groove or lip at the bottom for supporting the chimney, the whole being substantially as described or represented.” The bill charged infringement by the manufacture and the sale of the invention described in the specifications; and the proofs showed that the defendants had largely engaged in making and selling burners in all material respects like that described in the patent, unless the spiral wire wound into the edge of the deflector—the fðrm of spring used by defendants to press against the interior of the chimney—was to be regarded as a substantially different device from the elastic radial arms described by Collins: but it did not appear that they had ever made or sold any chimneys to accompany such burners. It was contended on the one side that in this there was no infringement, since the claim was to be construed as covering a combination of instrumentalities into which the chimney entered as an essential element; the Rule of law being invoked that a combination cairn is not infringed unless all the elements of the combination are used. On the other hand, it was urged by the complainants that, although in the claim reference was made to the chimney, yet as this device was not set forth in the specification as essential to the patentability of the combination of the chimney-rest and the deflector, and as Collins' object was to combine the deflector with a rest in such manner as to support the chimney both vertically and laterally without the and of any other device, and at the same time to keep the lower part of the chimney cool, the claim should be construed as covering, in fact, only the combination with the elevated deflector provided with peripheral springs of the concavo-convex chimney-rest pierced with holes for the passage of air. The enunciation of invention contained in the specifications of the patent bears upon this point, and is in these words: “The main purposes of my invention, or the principal part thereof, are, not only to keep the glass chimney of the lamp—or, in other words, the lower part of such chimney—in a cool condition, so that a person taking hold of such part with his hand can readily remove the chimney from the rest of the lamp, but to support the chimney without the use of a spring-catch and other devices that are ordinarily used.” But, further, it was contended that if the chimney by reason of being included in the claim was an essential part of the combination as patented, still it must be held that there was virtually an infringement by the defendants, even in the burners made by them and sold unaccompanied with chimneys. It was urged that the cases in which it had been held that the manufacture and sale of a combination containing only a part of the elements of a given patented combination did not constitute an infringement, were cases where the combination manufactured, although a part only of the patented combination, was useful in itself, independent of the parts omitted, and was actually designed for such use only, and not to be associated with the other parts of the patented combination; but it was contended that where, as in the case at bar, the combination manufactured and sold, containing less than all the elements of the patented combination, is made and sold with the express purpose of having the other elements of the patented combination added, and was useless without such addition, the case is entirely different—that in such case the one who makes and sells the minor combination knowingly and willfully commits a part of an act the whole of which constitutes infringement; and that he is, therefore, guilty of the charge of infringement, because he has participated in the infringement. Infringement of a patented combination, it was insisted, does not consist alone of putting the parts together; it commences when the unauthorized party begins to make the parts with the intention of completing them and putting them together, and at any stage of progress he is liable as an infringer. If the different parts are made by different persons, they jointly infringe the patent, and are liable both jointly and severally, and this whether the work is done in the same shop or in places remote from each other.]3

William B. Wooster, John S. Beach, and George Gifford, for plaintiffs.

Charles R. Ingersoll, Charles M. Keller, and Charles F. Blake, for defendants.

77

WOODRUFF, Circuit Judge. The complainants sue, as the assignees and owners of letters patent granted September 19th, 1865, to Michael H. Collins, for an improvement in lamps for an alleged infringement by the defendants, praying an injunction and an account of the gains and profits made by the defendants by the unlawful manufacture and sale of the invention so patented. The answer puts the complainants to proof of the patent, and of their title as assignees, denies that the defendants have infringed the patent, and alleges that, if the patent recited in the bill of complaint shall be construed to cover anything contained in lamps heretofore and now manufactured and sold by the defendants, then, and in that case, such letters patent are, to that extent, void, for want of novelty.

Upon the trial, the defendants rested their defence solely upon two grounds—want of sole title in the plaintiffs, and the non-infringement of the patent by the defendants. The court is, therefore, relieved from any examination of the testimony and documents which were apparently intended to show that Collins was not the first inventor, or any other proofs, except such as bears directly upon the two points above mentioned.

1. As to the complainants' title. They first show that, on the 23d of September, 1867, Michael H. Collins was, by the probate court of the county of Suffolk and state of Massachusetts, appointed guardian of the person and estate of his minor child, Florence H. Collins, upon his own petition and her nomination, and upon the giving of bonds in the form required by the statutes of that state. They next produce an instrument dated September 24th, 1867, which recites the granting of the foregoing and other patents to him, the said Michael H. Collins, that the said Florence E. Collins and Frances M. Collins have become the owners of the said invention for the territory of the United States, that Frances M. has assigned her interest to Sylvester W. Warren, that the said Michael has been appointed guardian of the said Florence E., whereby he is empowered to dispose of all the real and personal estate, goods, chattels, &c, of the said Florence E., and that it appears to the said Michael to be for the interest of his ward that her interest in the patents should be sold. It thereupon, in consideration of $50, sells, assigns, &c, to Warren, all the right, title, and interest the said Florence has in the patent right and in the invention, by virtue of an assignment to her and Frances M., dated February 12th, 1867. The instrument is executed, under seal, by the said Michael, as guardian of the said Florence. Next, an assignment by Frances M., dated, also, September 24th, 1867 (reciting, also, the assignment of February 12th, 1867, by Michael H. Collins to her and Florence E.), whereby, in consideration of $50, Frances M. assigns to Warren. Next, an assignment under the same date, by the said Sylvester W. Warren to the said Michael H. Collins, in consideration of $50, assigning to the latter the same patent, for the territory of the United States. Next, an assignment, dated December 24th, 1867, which recites the granting of the patent, the assignment thereof to Florence B. (a minor daughter) and Frances M. Collins, and that said rights had been attempted to be reconveyed to the said Michael, but that some doubt exists as to the precise effect of said conveyances, and therefore, in consideration of $30,000 paid to him, the said Michael, in his own behalf, and as guardian to the said Florence E., by the complainants in this suit, he, the said Michael, in his own right, and as guardian of the said Florence E., assigns to the complainants the said letters patent and the invention secured thereby, and all rights of re-issue, extension, &c. Finally, an assignment under date of December 25th, 1867, reciting a doubt whether, Frances M., being the wife of Michael, received or now holds any interest in the patent, by the conveyance to her by her husband, and therefore the said Michael and Frances M., husband and wife, assign all the interest which she may have in the patent or invention, to the complainants herein.

The defendants insist, that Michael H. Collins, as guardian of Florence E., had, under the laws of Massachusetts, no authority to sell her interest in the patent, without the order or license of one of the courts of that state, having jurisdiction for that purpose; and that the complainants, therefore, own only one-half of the patent (as tenants in common with her), and cannot maintain this suit without her presence as a party. The want of parties, not having been set up or suggested in the defendants' answer herein, cannot avail, unless the case is one in which the court cannot proceed to a decree between the parties before the court, without prejudice to the rights of those who are proper to be made parties, but who are not brought into court. Whether the suggestion of want of parties, first made on the trial, has any sufficient foundation in fact, depends upon the construction and effect of the statutes of Massachusetts. It was claimed to be apparent on the face of the assignments, that Michael H. Collins had practised a fraud upon his infant daughter, through the form of a sale of her interest for a consideration of $50, with intent that that interest should be immediately conveyed to him by the apparent purchaser, and so it was plain that he made use of his guardianship for the mere purpose of obtaining title to his ward's property, that he might sell the entire patent for the large consideration of $30,000 paid to him by the complainants. Whatever reason the assignments of the 24th of September, 1867, furnish for such a suspicion, the actual transfer to the complainants is free from any such appearance of fraud. That instrument recites the doubt of the effect of the previous sale, and, in appropriate form, acknowledges the receipt of the full consideration 78in his own behalf, and as such guardian, and sufficiently charges him, in his capacity of guardian, with accountability for the actual proceeds of sale. If, therefore, he had authority to sell, the complainants, being plainly bona fide purchasers, acquired good title to the whole patent. This question of authority must be determined by considering the effect of a statute of Massachusetts. Independent of the particular statute in question, it is not doubtful, that a guardian of the person and estate of an infant, appointed by the court of probate, has, as incidental to his office and duties, the power to sell personal property of his ward. His duty to pay debts, and to provide for the support, maintenance, and education of the ward, and, generally, to manage the estate, and his trust, indicated and expressed in the bond he is required to give, conditioned to manage, dispose of, and apply the same, and to account for all property and the proceeds thereof, all imply the power of the guardian in this respect. In this management, he is under a rigid responsibility, not only for the property but for its management and disposal for the best interest of the ward. If, therefore, he assumed to sell, for investment in other property, and, especially, if he ventured to change the nature of the property by investing in real estate, he would incur the hazard of an accounting in that respect, it may be many years afterwards, in which, in case of depreciation, the discretion exercised by him might be assailed and impeached, and he be subjected to loss on the one hand, and, on the other, the estate might be depreciated, notwithstanding the good faith of the guardian. And yet, at times, the interest of the ward may often be greatly promoted by change of investments, for the making of which the guardian would be unwilling to assume the responsibility.

The statute referred to enacts, that “the probate courts in the several counties, or the supreme judicial court, on the application of a guardian, or any person interested in the estate of a ward, after notice to all other persons interested therein, may authorize or require the guardian to sell and transfer any stock in the public funds, or in any corporation, or any other personal estate or effects held by him as guardian, and invest the proceeds thereof, and all other moneys in his hands, in real estate, or in any other manner that shall be most for the interest of ah concerned. Said courts respectively may make such further order, and give such directions, as the case may require, for managing, investing, and disposing of the estate and effects in the hands of the guardian.” Gen. St. Mass. c. 109, § 22. It is argued, that this statute has taken away the power of the guardian to sell any personal estate of his ward without an order of court, and that a sale and transfer by the guardian, without such order, is void, and confers no title on the purchaser. I do not think that this was the design of the statute, or that such is its effect. It unquestionably gives jurisdiction to the courts named summarily to control the guardian in this respect. So, also, it gives them power to control him generally in the management of the estate. But, the construction claimed would imply that he can, since the statute, do nothing lawfully except under a special judicial order obtained for the purpose. This jurisdiction is useful, in a high degree. It looks chiefly to the investment, and change of investment, of the estate. It enables the guardian to obtain advice and protection. He may often think a change of the property, and even an investment in real estate, best for the interest of his ward, and yet be unwilling to make it at the hazard of the result, and of the judgment which may be passed thereon at the end of, perhaps, very many years. He can, therefore, apply to the court, and obtain recorded judicial approval, which will be his conclusive protection in the future. So, also, when any party interested in the estate is dissatisfied with the management of the estate, or deems a change in the investments desirable, he can apply, and, if it seem best, the courts may require change of investments, or make other order touching the management or disposal of the property. This summary jurisdiction is conservative, it may be availed of by all parties, it protects the guardian in circumstances of doubt, and enables him to make investments not within the general line of his duty as guardian, and to make changes of investment without liability therefor on an accounting which may be required long afterwards, when, perhaps, unforeseen events make the acts seem negligent or improper; but it was not intended, and it does not operate, to deprive the guardian of power to sell personal property. In doing so, he acts subject to responsibility for good faith, proper prudence, and the proper use of the proceeds; and, in such case, the purchaser obtains title to the property sold.

This view of the complainants' title renders it unnecessary to say what, in this suit, would be the effect of a holding that they were not sole owners of the patent. The objection that Florence E. is not a party to the suit, not having been made either by plea or answer, would not necessarily defeat the suit. Even then, the complainants have title, though not as sole owners. At law, in an action for a tort, such nonjoinder could only be urged by plea in abatement, or in diminution of damages; and, in equity, if the court were of opinion that complete justice could be done between the parties before the court, without prejudice to the absent party, it might perhaps proceed, treating the defendants as having waived the objection, or, at most, in such a state of the case, direct the absentee to be made a party, if that was deemed necessary. The conclusion, however, that the complainants have title, disposes of the objection.

2. The ground upon which alone the defendants claimed, on the trial, that they had not infringed the patent, is this—that the patent 79is for a combination of several parts, together constituting the improved lamp described in the patent; and that the defendants have only made and sold some of the parts of that combination, and cannot, therefore, be charged as Infringers. The patent is, in terms, for “a new and useful improvement in lamps.” The specification describes “the main purpose of the invention, or the principal part thereof,” to be, not only to keep the lower part of the glass chimney of the lamp cool, so that it may readily be removed by the hand, but, also, to support the chimney without the use of a spring catch, or other devices, such as are ordinarily used. It thereupon proceeds to describe what is ordinarily called the burner of the lamp, namely, that portion which holds the wick tube, and which is to be screwed into the cap of the reservoir or body of the lamp, containing the oil or fluid used for combustion, consisting of an. “air induction annular plate” at the bottom, convex, and provided with holes, to admit the air, and turned slightly up at the outer edge, to receive and sustain the chimney. The wick tube rises above it, and near, but just above the top, is surrounded by an “umbelliferous cone, or deflector,” which extends outward to the sides of the chimney, and, the outer edge being cut or slit radially, the divided edge forms springs, which press against the interior of the chimney, and sustain it firmly in its upright position. The parts of the deflector between the slits being inclined downward, and being elastic, are adapted to receive the chimney, though there be irregularities and differences in the interior dimensions of chimneys which may be used. Other details are given pertaining to the construction, mode of operation, and uses of the parts, which it is not necessary to mention. It must suffice to say, that what is called the burner embraces all the metallic portion of the lamp containing, surrounding, or placed above the wick, and to be screwed into the cap of the reservoir. The specification also describes the glass chimney to be used, thus: “The lower part of the chimney, or that portion which extends from the deflector to the chimney rest, is constructed tubular and cylindrical. Above this part, the chimney bulges out, and finally is contracted to its top, in manner as shown in the drawings;” and, in the operation of the lamp, stress is laid upon the effect of perforations in the chimney rest, in its convex sides, through which the air, passing in currents, is alleged to impinge against the inner surface of the cylindrical portion of the chimney between the deflector and the chimney rest, and keep that part of the chimney cool, so that it may readily be seized between the thumb and finger, when it is desired to remove it.

The claim is as follows: “I claim the improved lamp, as not only constructed with its cone or deflector, F, and its chimney rest, D, and chimney, arranged with respect to each other as described, but as having the said deflector provided with peripheral springs, or the same, or the slits, h, h, and the rest, D, made concavo-convex, and provided with an annular groove or Up at the bottom, for supporting the chimney, the whole being substantially as described or represented.” The proof shows, that the defendants from the fall of 1867, have been engaged in the manufacture and sale of lamp burners, called the “Comet Burners,” which were not claimed on the trial to differ in any material particular from the patented invention, the principal apparent difference being in the substitution of a spiral elastic wire wound into the edges of the deflector, to press against the interior of the chimney and maintain its upright position, instead of the slit edge of the deflector itself, formed into springs, performing the same office. This however, was not claimed to be a substantial difference, but was treated by both parties, for the purposes of the case, as (which, I think, it unquestionably is) an equivalent device, operating in the same manner and producing the same effect. But, although it is proved that the defendants used their burners, so manufactured, in their store, with chimneys placed thereon, to exhibit their burners to customers, in order to make sales, and to demonstrate their superiority over other burners, there is no proof that the defendants ever manufactured or sold a chimney; and, hence, they insist, that, having made and sold only some of the parts included in the patented combination, they are not liable in this suit. It is quite obvious, that the distinguishing feature of the Invention of Collins is the burner, with its chimney rest, a deflector having peripheral springs, to sustain the chimney without the and of a catch or screw, and with air passages operating, when in use, to keep the lower part of the chimney cool, and, obviously, tending, by this means, and by the greater elevation of the flame, to prevent the lower portion of the burner, and top of the reservoir, from becoming unduly heated. It is, also, clear, and was proved, that the burner alone, or the burner attached to the reservoir, is utterly useless. A chimney must be applied, in order to its operation. So, also, a chimney without a burner is wholly useless.

It was claimed, in behalf of the complainants, that the chimney is no material part of the invention, as patented, and, therefore, that the defendants have made and sold all that is material in the patent. I incline, however, strongly to the opinion, that the patentee, in his specification and claim, instead of claiming the burner as new, and securing the exclusive right in respect to that, has claimed it in combination with a chimney, and must stand by his patent under that construction. In that view of the construction of the patent, the case stands thus: The complainants having a patent for an improved burner in combination with a chimney, the defendants have manufactured and sold extensively the burner, leaving the purchasers to supply the 80chimney, without which such burner is useless. They have done this for the express purpose of assisting, and making profit by assisting, in a gross infringement of the complainants' patent. They have exhibited their burner furnished with a chimney, using it in their sales room, to recommend it to customers, and prove its superiority, and, therefore, as a means of inducing the unlawful use of the complainants' invention. And now it is urged, that, having made and sold burners only, they are not infringers, even though they have distributed them throughout the country in competition with the complainants', and have, to their utmost ability, occupied the market, with the certain knowledge that such burners are to be used, as they can only be used, by the addition of a chimney. Manifestly, there is no merit in this defence, and it must be regretted if the law be not such as will protect the complainants against this palpable interference. If the complainants were to succeed in finding those who manufactured chimneys for the express purpose of selling them to be used on these burners, the latter could clearly urge the same, if not a better, defence, to a prosecution; and so the complainants would be driven to the task of searching out the individual purchasers for use who actually place the chimney on the burner and use it—a consequence which, considering the small value of each separate lamp, and the trouble and expense of prosecution, would make the complainants helpless and remediless.

The rule of law invoked by the defendants is this—that, where a patent is for a combination merely, it is not infringed by one who uses one or more of the parts, but not all, to produce the same results, either by themselves, or by the and of other devices. This Rule is well settled, and is not questioned on this trial. The Rule is fully stated by Chief Justice Taney, in Prouty v. Buggies, 16 Pet. [41 U. S.] 336, 341, and in other cases cited by the counsel. Byam v. Farr [Case No. 2,264]; Foster v. Moore [Id. 4,978]; Vance v. Campbell, 1 Black [66 U. S.] 427; Eames v. Godfrey, 1 Wall. [68 U. S.] 78, 79. But I am not satisfied that this Rule will protect these defendants. If, in actual concert with a third party, with a view to the actual production of the patented improvement in lamps, and the sale and use thereof, they consented to manufacture the burner, and such other party to make the chimney, and, in such concert, they actually make and sell the burner, and he the chimney, each utterly useless without the other, and each intended to be used, and actually sold to be used, with the other, it cannot be doubtful, that they must be deemed to be joint infringers of the complainants' patent. It cannot be, that, where a useful machine is patented as a combination of parts, two or more can engage in its construction and sale, and protect themselves by showing, that, though united in an effort to produce the same machine, and sell it, and bring it into extensive use, each makes and sells one part only, which is useless without the others, and still another person, in precise conformity with the purpose in view, puts them together for use. If it were so, such patents would, indeed, be of little value. In such case, all are tort-feasors, engaged in a common purpose to infringe the patent, and actually, by their concerted action, producing that result. In a suit brought against such party or parties, a question might be raised, whether all the actors in the wrong should be made parties defendant; but I apprehend, that, even at law, and, certainly when non-joinder was not pleaded, the want of all the parties would be no defence. Each is liable for all the damages. Here, the actual concert with others is a certain inference from the nature of the case, and the distinct efforts of the defendants to bring the burner in question into use, which can only be done by adding the chimney. The defendants have not, perhaps, made an actual pre-arrangement with any particular person to supply the chimney to be added to the burner; but, every sale they make is a proposal to the purchaser to do this, and his purchase is a consent with the defendants that he will do it, or cause it to be done. The defendants are, therefore, active parties to the whole infringement, consenting and acting to that end, manufacturing and selling for that purpose. If the want of joinder of other parties could avail them for any purpose (which is not to be conceded), they must set it up as a defence, and point out the parties who are acting in express or implied concert with them. Nor is it any excuse, that parties desiring to use the burner have all the glass manufacturers in the world from whom to procure the chimneys. The question may be novel, but, in my judgment, upon these proofs, the defendants have no protection in the Rule upon which alone they rely as a defence against the charge of infringement. Independent of this question, the proofs show an actual use by the defendants of the entire subject of the patent; but, as the conclusion reached charges them as manufacturers and vendors, it is not material to enquire whether that use is within the scope of the bill of complaint, or would, by itself alone, entitle the complainants to charge them as infringers, in this suit. The complainants must have a decree for an injunction and account, as prayed in the bill of complaint.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.

the lamp, B the wick-tube, E the chimney, & the chimney-rest, and F the cone or deflector, provided around its upper edge with peripheral springs, or having the edge cut into radial slits, h, the function of which is to press against the glass of the chimney and hold it in place.]2

the lamp, B the wick-tube, E the chimney, & the chimney-rest, and F the cone or deflector, provided around its upper edge with peripheral springs, or having the edge cut into radial slits, h, the function of which is to press against the glass of the chimney and hold it in place.]2