1099

Case No. 16,301.

27FED.CAS.—70

UNITED STATES v. SIXTEEN CASES OF SILK RIBBONS.

[12 Int. Rev. Rec. 175.]

District Court, S. D. New York.

1870.

VIOLATION OF CUSTOMS LAWS—FORFEITURE FOR UNDERVALUATION—IMPORTS BY MANUFACTURERS—EVIDENCE OF MARKET VALUE—ESTOPPEL.

[1. Id cases of importation of goods by the manufacturer thereof, the value at which he is required, by the act of March 3, 1863, to invoice them, is the actual market value at the time and place of manufacture.]

[2. By “market value” is meant the price at which the manufacturer holds them for sale, the price at which he freely offers them in market, the price which he is willing to receive, and purchasers are willing to pay, in the ordinary course of trade. Following Clicquot's Champagne, 3 Wall. (70 U. S.) 114.]

[3. The law presumes that there was at the time and place of manufacture an actual market value for the goods, and no evidence can be received to show that there was not in fact such an actual market value.]

[4. Among the best evidences of market value would be a series of sales, general in their character, not accompanied by any exceptional circumstances tending to make one or more of such sales higher or lower than it would otherwise be; also a single sale, if made in the ordinary 1100course of trade. Other evidence would be offers by merchants or manufacturers to sell to persons supposed by them to come in good faith as buyers, such offers being made in the usual course of trade, and under such circumstances as generally attend the sale of merchandise.]

[5. It is only in cases where such evidence as the foregoing is wanting that it becomes proper to resort to such inferior evidence as the actual cost of the raw materials to the manufacturer, with the addition of a manufacturer's profit. Even in such eases this cost is not to be received as a substitute for market value, but only an evidence tending to show market value.]

[6. In cases where such inferior evidence is resorted to, the cost of the raw materials is not to be based upon the actual price paid for them by the manufacturer, if he purchased them long prior to making them up, and at a time of depression in the market, but rather upon the actual price of raw material at the time when the manufacture of the goods was completed.]

[7. The fact that the United States consul at the place of exportation has, in compliance with his duties, certified that the invoice is correct, and the fact that the goods have been appraised, entered, and delivered to the consignee by the officers of the customhouse, on the theory that the invoice stated the true value, are not conclusive upon the question of a fraudulent undervaluation in a proceeding 10 forfeit the goods. The offence, if any, is complete when the entry is made, and it is immaterial that the invoice was used in the estimation of the duties; for the government is not bound, in respect to the question of forfeiture, by the acts of its officers based upon false and fraudulent statements.]

[8. Evidence of the value of goods in New York cannot be received, in a suit to forfeit them on the grounds of an entry by means of a false invoice, except as evidence of value at the place of exportation, and to contradict other evidence given in regard to the value there.]

[9. Evidence of prior undervaluations by the same importers is admissible only for the purpose of showing the intent with which the present undervaluation was made, and can only be considered by the jury in case they find that there is in fact an undervaluation in the present case. Nor can alleged prior undervaluations be considered for this purpose, unless the jury are satisfied that such prior undervaluations were knowingly made.]

[10. The rule prescribed by Act 1799, § 71 (1 Stat. 678), that, where probable cause of seizure is shown, the burden of proof is cast upon the claimants, is in force under the act of 1863, though the latter act is silent on this subject. Whether probable cause is shown is a question for the court.]

[This was a proceeding to forfeit sixteen cases of silk ribbons, on the ground that the same were entered by means of a false invoice.]

Edwards Pierrepont, Dist. Atty., and William G. Choate, for the United States.

Edwin W. Stoughton, Sidney Webster, James B. Craig, and O. Bainbridge Smith, for claimants.

BLATCHFORD, District Judge (charging jury). The prosecution in this case is instituted on the seizure of the goods, and a suit in rem against the goods seized is promoted for their condemnation and forfeiture under two statutes of the United States which apply to the subject. The first one is the fourth section of the act of May 28, 1830 (4 Stat. 410), and the second is the first section of the act of March 3, 1863 (12 Stat. 737). The substance of the act of 1830 is, that if any invoice on which foreign goods are entered at any customhouse is made up with an intent, by a false valuation to evade or defraud the revenue, all the goods embraced in the entry made on such invoice are forfeited. If any article inserted in the invoice has a false valuation put upon it, with an intent to evade or defraud the revenue, then not only that article, but all other goods embraced in the same invoice, are forfeited to the United States. It will not be necessary to call your attention any further to the act of 1830.

The questions which arise in this case under the act of 1863 are substantially the same, but there are certain provisions of the act of 1863 to which it is necessary I should call your attention. The first section of that act provides that all invoices of goods imported from any foreign country into the United States shall be made in triplicate,—that is, there shall be three sets of invoices signed by the person owning or shipping the goods, if the same have actually been purchased, or by their manufacturer or owner, if the same have been procured otherwise than by purchase, or by the duly authorized agent of such purchaser, manufacturer, or owner. The invoice so signed must, at or before the shipment of the goods, be produced to a consul, vice-consul, or commercial agent of the United States nearest the place of shipment, and must have endorsed thereon, when so produced, a declaration signed by such purchaser, manufacturer, owner, or agent, setting forth that such invoice is in all respects true. That is to be a declaration not on oath, and is to state what the invoice contains, if the goods were obtained by purchase, and are subject to ad valorem duty,—a duty by a percentage on the valuation,—a true and full statement of the time when and place where the same were purchased, and the actual cost thereof, and of all charges thereon, and that no discounts, bounties, or drawbacks are contained in the invoice but such as have actually been allowed thereon. When the goods are obtained in any other manner than by purchase—as when they are sent by their manufacturer, or when they are presented to the individual as a gift—then this declaration is to state that the invoice contains the actual market value thereof at the time and place when and where the same were procured or manufactured, and that no different invoice has been produced or will be furnished to any one. The person producing this invoice to the consul must, at the same time, declare to the consul at what port it is intended to make entry of the goods. This presentation to the consul of the invoice, accompanied by 1101the declaration, is the second stage of the proceeding. The third stage is this: The consul must endorse upon each one of the three invoices a certificate, under his hand and seal, stating that the invoice has been produced to him, with the date of its production, the name of the person by whom produced, and the port in the United States at which it shall be the declared intention to make entry of the goods. Thereupon, the consul must hand back to the person producing the three invoices, one of them, to be used in making entry of the goods; he must file the second one in his own office, to be there carefully preserved; and he must transmit the third one to the collector of the port where it is intended to make entry of the goods. Such is the disposition to be made of the three sets of invoices, with the three declarations, and the three certificates of the consul. The statute then provides that no goods imported into the United States after the first day of July, 1863, shall be admitted to entry, unless the invoice shall in all respects conform to the requirements above mentioned, and shall have such certificate of the consul. Therefore the invoice must come from the foreign country, containing, in the case of the manufacturer, the actual market value, accompanied by the declaration, not on oath, and a certificate of the consul, to the effect that the invoice has been produced to him, and that the goods are to be entered at a specified port. The statute goes on to say that no goods shall be admitted to entry unless the invoice be verified—now is the first time an oath appears in the matter—unless the invoice be verified, at the time of making the entry, by the oath or affirmation of the owner or consignee, or the authorized agent of the owner or consignee of the goods, certifying that the invoice and the declaration are in all respects true, and were made by the person by whom the same purport to have been made, nor, except as thereinafter provided, unless the triplicate invoice transmitted to the collector shall have been received by him. You thus see the machinery provided—the invoice made up abroad, in a certain way, the declaration accompanying it and the certificate of the consul, the appearance of those three papers at the customhouse, and the addition to them, at the customhouse, of the oath or affirmation that the invoice and declaration are in all respects true.

The act of 1863 then goes on to make this provision, under which this prosecution is brought: “If any such owner, consignee or agent“—that is, if the consignor abroad, or the consignee here, or the agent of either of them—“of any goods, wares or merchandise shall knowingly make, or attempt to make, an entry thereof by means of any false invoice or false certificate of a consul, vice-consul or commercial agent, or of any invoice which shall not contain a true statement of all the particulars hereinbefore required, or by means of any other false or fraudulent document or paper, or of any other false or fraudulent practice or appliance whatsoever, said goods, wares, and merchandise, or their value, shall be forfeited and disposed of as other forfeitures for violation of the revenue laws.” Any infraction of this provision forfeits all the goods embraced in the entry. * * * All the papers correspond with the machinery provided by law; and the question raised in this case is whether this entry was made by means of a false paper, and, if so, whether the paper was false to the knowledge either of these parties in Switzerland or of their agent or consignee here, who made the entry. Knowingly making an entry by means of a false paper, such as a false invoice or a false oath, where the fact that it was false was known to the agent or consignee here, forfeits the goods just as much as if the knowledge was possessed by the consignor abroad.

There have been heretofore before this court cases in regard to various descriptions of merchandise, involving the same questions that are now before you; and I have had occasion to charge juries heretofore on these subjects. I shall, therefore, in what I have to say to you, draw somewhat at large upon what I have heretofore said on like questions in some other eases. You have seen that the language of the act of 1830 is, that if the invoice is made up with an intent, by a false valuation, to evade or defraud the revenue, the goods shall be forfeited. The language of the act of 1863 is that if the entry, or the attempt to make the entry, is by means of a false invoice, and is done knowingly, the goods shall be forfeited. The only material and substantial apparent difference between the two statutes is that the one speaks of making up an invoice with intent to evade or defraud the revenue, and the other speaks of knowingly making an entry by means of a false invoice. “Intent to evade or defraud,” is the wording in the one case; “knowingly,” in the other. * * * In the case of a purchaser of goods, the cost to him to buy the goods abroad is assumed, as a general rule, by the law, to indicate the actual market value of what he buys, it being presumed that he buys at the ordinary actual market value; and, to put the purchaser upon the same footing with the manufacturer, to make no unjust discrimination against the purchaser, and In favor of the manufacturer, and to enable the government to collect substantially the same amount of duty, at the same ad valorem rate, on the same quantity of the same description of merchandise, whether shipped here for account of the purchaser of it, or for account of its manufacturer, the law requires the manufacturer, to invoice his goods, when he imports them, and enters them here as his I own, at their actual market value in the I principal markets of the country where they 1102were manufactured, no matter what their cost to him, no matter whether they cost more or less than such actual market value. The whole thing comes to this, in substance and effect—that the manufacturer is required to invoice them in this way, at what the purchaser is also required to invoice them at, for the purpose of producing uniformity. That is the theory and the object of the law; and its language endeavors to carry out that theory and object, as far as it is possible for human legislation to carry out a principle. * * * “Actual market value” has been decided by the supreme court of the United States in the case of Clicquot's Champagne, 3 Wall. [70 U. S.] 114, to mean the actual market value of the goods at Basle, in Switzerland, at the time of their manufacture, the price at which the manufacturer holds them for sale, the price at which he freely offers them in the market, the price which he is willing to receive for them if they are sold in the ordinary course of trade. That is a definition which commends itself to the good sense of every man. A manufacturer who sends his goods to this country under the circumstances under which the goods in this case were sent has no right to substitute, in his invoice, anything else for the actual market value. He has declared, in the first place, that the invoice contains the actual market value. In addition to that, there is the oath of his agent at the customhouse that the invoice contains the actual market value. Therefore, the first question for consideration will be, whether the invoices contain the actual market value of the goods at the time and place when and where they were manufactured; and, in the next place, if they do not, whether they were made up by the manufacturers with the intent to evade and defraud the revenue of the United States, or with a knowledge, either on their part or on the part of their consignee or agent here, who entered them at the customhouse, that the invoices did not contain such actual market value. * * *

It is quite apparent, in this ease, that the cost of the raw silk used in making these ribbons enters into the expense of making them to the extent of from seventy to eighty per cent, of the entire cost of manufacturing them; and, of course, the variation in the cost of making them must depend a great deal on the price of raw silk. It is also in evidence, both by Viollier and by the depositions on the part of the claimants, that there was a time, during the year 1866, when, in consequence of the apprehension of war, and of the existence of war between Austria and Prussia, there was an interruption of trade, the demand for ribbons lessened, and there was a fall in the price of raw silk; and that, after the war closed, raw silk advanced in price. As to when these things happened, I shall speak hereafter. I refer to the subject now, for the purpose of saying, that, if the claimants in this case purchased raw silk at low prices, and manufactured ribbons out of that silk, but did not have them completed and ready for market until raw silk had advanced considerably, and if they afterwards made out their invoices of such ribbons on the basis of the cost of raw silk bought at those low prices, it is manifest that the cost of the goods so arrived at would not represent their actual market value at the time when they became a completed manufacture, which is what the law of the United States requires. It would undoubtedly represent the cost of the goods to the manufacturer, because he procured his raw silk at a low price, and he had, or was entitled to, a market for his manufactured goods afterwards, at a price for those goods based upon an increased price of raw silk—a price to the benefit of which, as against him, the United States were entitled. This case furnishes an illustration of why the United States can never admit that a manufacturer shall invoice his goods at their cost to him, with a profit added, unless such cost, with the profit added, is in fact the actual market value of the goods when their manufacture is completed. He cannot invoice them at the price he paid for the raw silk which he put into the particular goods, with the other expenses of manufacture, and a profit added, unless the result is in fact the actual market value of the goods. If any such principle of valuation were to be admitted by the United States as cost with the profit added, the cost which, in reference to raw silk, the United States would have a right to insist upon in a ease like the present would be a cost based upon a price for raw silk at the advanced rate at which it stood when the goods were completely manufactured ready for market; otherwise the United States would be defrauded of that to which they are entitled by law. Therefore it is that no individual has any right whatever under any circumstances to substitute in his invoice for the actual market value cost, with a manufacturer's profit added. He must put in the actual market value. The manner in which he arrives at it is of no consequence. * * * The entries in this case show, there being three separate entries—one on the first invoice and two on the second invoice—that is, in each of the three entries, one case was designated and sent in the usual course of business to be appraised: and all of the invoices show that the invoices were accepted by the authorities at the customhouse as correct; that the duties were computed at the rate of 60 per cent, on the face of the invoices; that the government delivered the goods on the payment of that duty to the parties claiming them; and that afterwards the goods were seized. * * * The claimants state that not only in reference to the goods in question, but in reference to like goods which they had been in the habit of sending for a long time before to the United States, they made up their 1103invoices on the principle of arriving at the cost and adding 5 per cent, thereto, and calling that the market value. * * *

It is quite apparent, on the evidence, that the cessation of the war between Prussia and Austria sent up the price of raw silk. It is for you, in view of all the evidence on the subject, to determine when it was at its lowest point, and when it began to advance after the cessation of the war, with reference to the time of the completed manufacture of the ribbons under seizure. This is to be done, bearing in mind the principle of law I have laid down, that, if the cost of the goods, with the manufacturer's profit added, is the only means to which resort can be had to fix the market value of the goods, the government is entitled to the price of raw silk in the market, as entering into the goods, at the time of their completed manufacture. * * * On the subject of what resort you shall make to the different classes of evidence, the law is this: If these claimants, when Viollier and Farwell came there, believed that they came as customers, in good faith, intending to purchase ribbons, and if you shall believe that the offer to sell made by the claimants was a bona fide offer to sell on the terms named, uninfluenced by any considerations which would modify the apparent effect of the terms, you have a right to regard that offer as evidence to be taken into consideration in determining the question of the actual market value of the goods under seizure at the time and place of their manufacture; but if, on the evidence, you shall think that the prices given in the letter were influenced by the considerations I have mentioned in regard to smuggling, you will allow those considerations the weight to which they are entitled, and give to the letter, under those circumstances, the weight to which you shall think it is entitled on the question of actual market value, and also on the question of intent. The law, in all departments of its administration in courts of justice, always requires the best evidence to be produced of any fact. In regard to the actual market value of merchandise abroad, a series of sales, general in their character, not accompanied by any exceptional circumstances tending to make any one or more of such sales higher or lower than it would be but for such exceptional circumstances, or even a single sale, in the ordinary course of trade, is one of the best evidences of market value. This rule will apply to the Bachofen sale, taking into consideration the date of it, the 28th of June, and all the circumstances surrounding it. So, also, offers by merchants or manufacturers to sell their goods to persons who are supposed by them to come as buyers, in good faith, such offers being made in the usual course of trade, under such circumstances as generally attend the sale of merchandise, are among the best evidences of the actual market value of the goods in respect to which the transactions take place. It is only when such evidence is wanting, in a case of this kind—it is only when you are unable to arrive at the market value of the goods from actual sales of similar goods about the same time, or from offers to sell, made under the circumstances which I have specified as necessary, in respect to the same goods, or goods of the same quality—that you have a right to resort to an inferior class of evidence, as evidence of market value, that is, to the cost, with a manufacturer's profit added. But, as I said before, if, in this case, you shall consider that there is no evidence of actual sales at Basle of goods like those under seizure, and no evidence of offers by claimants to sell at Basle similar goods, from either of which you can arrive at a conclusion as to the actual market value at Basle of the goods in the invoices in question, and if you shall then have to resort to the cost of the goods with a manufacturer's profit added, you will not be authorized to compute such cost on the basis of the cost of the raw silk to the claimants, if you shall find that the claimants were paying for raw silk a higher price, at the time of the completion of the manufacture of the goods, than the actual cost to them of the same quality of raw silk as that which went into the manufacture of such goods. The government is not bound to accept such low cost of the raw material. It is entitled to the benefit of the price of the raw material at the time when the goods were completed in their manufacture. * * * Evidence is introduced by the government on the question of intent, it being claimed that the invoices of 1866, and particularly the invoice of the 8th of January, 1866, were undervalued knowingly by the claimants; and that, therefore, in case you shall find that the invoices in suit were undervalued, you must find that such undervaluation could not have been an accidental undervaluation, but that there was a design running all through, and a knowledge on the part of the claimants. * * *

In determining the question of knowledge or intent on the part of the claimants, in the undervaluation of their goods in the invoices, if you shall find that such undervaluation was made, the question for consideration will be, whether such undervaluation was made knowingly, that is, with a knowledge, on the part of the claimants, that the value stated ought to have been higher, in order to be the actual market value, or designedly; or whether it was the result of honest mistake or an accident. If you shall find that it was made knowingly or designedly, your verdict must be for the United I States; otherwise, for the claimants. So, all so, if you shall find that the claimants knowingly or designedly stated, in any invoice, a value less than the actual market value, knowing what that actual market value was, and that it was greater than the value stated in the invoice, it makes no difference as to what was the motive, or the reason, or the process of reasoning, on the part of the claimants, 1104upon or by which they arrived at the value stated in the invoice.

The question as to the meaning of the word “knowingly,” in the act of 1863, has been before the supreme court of the United States. The difference in language between the act of 1830 and the act of 1863, the former requiring an intent to evade or defraud the revenue, and the other requiring that the party shall knowingly make or attempt to make an entry by means of a false invoice, has been called to your attention; but there is no real difference in the meaning of the two expressions, as was decided by the supreme court in the Case of Clicquot's Champagne, before referred to. In that case, the district court in California was requested to charge the jury “that the word ‘knowingly,’ in the first section of the act of March 3, 1863, means, in connection with the language which accompanies and surrounds it, ‘fraudulently.’ “The district judge refused to give that instruction, and held that such was not the law, and his charge on that subject was approved by the supreme court, to which the ease went, and which affirmed the judgment, in these words: “The court below was pressed to instruct the jury that ‘knowingly’ is used in the statute as the synonym of ‘fraudulently.’ The instruction given was eminently just, and we have nothing to add to it.” The instruction given by the district court was this: “With regard to the question of intent, I am asked to charge you, that you should be convinced that these goods, if invoiced below their market value, were invoiced fraudulently below their market value. The previous statutes passed by congress had introduced, in many instances, the word ‘fraudulently,’ had defined the offence to be, making a false invoice ‘with intent to defraud’ the revenue, or evade the payment of duties.” The learned judge here refers to the language of the act of 1830. He proceeds: “This statute,” the statute of 1863, “apparently, ex industria, omits these expressions, and substitutes the words ‘if the owner,’ etc., shall knowingly make an entry by means of any false invoice, etc. I do not feel at liberty, when the legislature had left out the word ‘fraudulently,’ and inserted the word ‘knowingly,’ to reinstate the word ‘fraudulently.’ At the same time, I am bound to say, that I cannot conceive any case where an entry could be knowingly made by means of a false invoice, unless it were fraudulently made. I do not tell you, in terms, that you are obliged to find that the entry was made fraudulently, but you are obliged to find that it was made knowingly, by means of a false invoice; and, for myself, I cannot imagine any case where it could be knowingly done, without being fraudulently done. What, then, shall we understand by this word, ‘knowingly,’ as here employed? It is, that, in making out this invoice, and in swearing before the consul that such was the actual market value of the goods, the claimant knew better, and that he was swearing falsely.” So, also, in regard to Thomass, in making the entry. If, when he swore on that entry, that the invoice and the declaration were true, and that the invoice contained the actual market value of the goods, he knew better, and knew that he was swearing falsely, he did it knowingly. In all the cases that have come before the courts of the United States, on this subject, a distinction is drawn between an undervaluation that takes place by mistake or accident and one that does not take place by mistake or accident. Where the undervaluation is shown to have occurred by mistake or accident of course it is excused; but where it is not shown to have occurred by mistake or accident it necessarily follows that it must have been made, in the sense of the statute, knowingly or with an intent to defraud the revenue. On that subject I cannot do better than to read to you a few words from the judgment of an eminent judge in a similar case—Judge Hopkinson, of Pennsylvania. The case is that of U. S. v. Twenty-five Cases of Cloths [Case No. 16,563]. The judge says: “Supposing that you shall find that these goods are undervalued in the invoices, how are you to decide upon the fraudulent, intent or design? In doing this, you will be influenced by the extent of the undervaluation. Is it enough to have been a temptation to fraud? Could it, on a large business, afford a great profit? Does it run, generally, through all the invoices? or is it only an occasional undervaluation that might have happened by accident, by mistake, without any design?” That shows the view of this learned judge as to the true test of this question of intent Was it by accident or mistake on the one hand, or by design on the other? If it was by design or intent, then it was not by accident or mistake. If it was by accident or mistake, then it was not with intent or design. * * * The law presumes that there was at the time and place of the manufacture of the goods seized an actual market value thereof, and no evidence can be received or considered, under the law and under the oaths to the invoices, to show that there was not in fact such actual market value thereof. The cost of the goods will come under consideration, if at all, not as a substitute for market value, but merely as an item of evidence on the question as to what was the actual market value. Therefore, you must assume in this case that there was an actual market value for these goods at the time and place of their manufacture, the only question being to ascertain what such actual market value was. The claimants had no right to adopt any other standard of value than such actual market value; nor do I understand them as claiming that they had such right. They have stated in their declarations, and their agent has sworn in their oath on such entry, that such invoice 1105contains the actual market value; and their claim is not that they had a right to set forth anything except the actual market value, but that the actual market value was the cost with the manufacturer's profit added at the per centage named in the testimony, and that such actual market value was no greater, according to their idea of actual market value. So, also, the claimants were required to state in their invoices the actual market value of their goods at the time and place of their manufacture, not only without regard to the cost thereof, but without regard to the profit or loss which might result from their consignment thereof, or any loss which may be shown in the end to have resulted therefrom. If they chose to take the cost and add a profit, and made up the actual market value in that way, and it turns out in the end that “that is the actual market value, very well; but if it turns out in the end that that is less than the actual market value, the claimants cannot maintain under the law that they had a right to put in place of the actual market value the cost with the manufacturer's profit added. Nor is the manufacturer relieved or excused from stating in his invoice such actual market value, or justified in adopting any other standard of value, because he may not himself make sales at home of similar goods, but may consign all such goods for sale to foreign markets. Although he may adopt such course of trade, he is nevertheless required to state in his invoice the actual market value of such goods at the time and place of their completed manufacture.

Very many remarks were made to you in the course of the trial and summing up upon the subject of informers, the seizure of books and papers, the seizure of goods, and other subjects of a like character, which are entirely foreign from this case, and upon which I shall spend no time, except to say they have nothing to do with any question on which you are to pass.

I have been requested by the counsel for the claimants to give you seventeen instructions which have been presented to me. Most of them are covered by what I have already said, but there are some things in them to which it is my duty to refer in order that nothing material may be omitted.

The first proposition is a correct one, and I charge you accordingly: “There are two questions of fact to be considered and determined by the jury: (1) Were the ribbons under seizure invoiced by Frey, Thurneyson & Christ at the actual market value thereof at the time when and in the country where the same were manufactured? (2) If they were not so invoiced was the false valuation made knowingly, or with Intent to evade the payment of duty legally chargeable thereon? Before the jury can return a verdict for the United States in this case, they must answer both of these questions in the affirmative,”

The second, third, fourth, and fifth requests relate to matters that are kindred to each other. I do not charge in accordance with those requests, except to the extent that I shall hereafter indicate. The substance of the second request is, that, inasmuch as the invoice is required to be produced to a consul abroad, accompanied by a declaration endorsed thereon, and inasmuch as the consul is required to place upon it a certificate of a certain character, and inasmuch as the law requires that no invoice shall be admitted to entry unless it has this certificate, and inasmuch as it also requires that no consular officer shall certify any invoice unless he shall be satisfied that the statements made in it by the manufacturer are true, and inasmuch as a punishment is imposed upon the consul if he knowingly and falsely certifies to any invoice, and inasmuch as all consular officers are to be governed by regulations and instructions to be given by the secretary of state, in respect to certifying invoices under the provisions of the first section of the act of March 3, 1863, and inasmuch as the secretary of state of the United States, by circular No. 59, dated April 20, 1866, officially instructed all consular officers that they will be held responsible for any want of truth and correctness in invoices certified by them, and will be expected to keep themselves informed as to the kinds, qualities, and market value of the merchandise exported from their respective districts to the United States, and to see that each invoice exhibits a fair and true description of the merchandise to which it relates, and contains a true statement of the price and value thereof, the jury are at liberty to presume that the consul did his duty as to investigating and certifying the correctness of the value of the ribbons stated in the invoices under seizure. I do not charge that.

I am also requested to charge the third proposition, which I do not charge. The substance of it is, that the law made it the duty of the collector here to cause the actual market value of the goods at Basle to be appraised by officers appointed for that purpose, and that, if the jury shall find that the collector failed to cause such appraisement to be made according to law, but seized the goods for undervaluation in the invoices, without any such appraisement, and delivered them to the importers on the payment of duty computed on the values contained in the invoices and stated in the entry, then they are permitted to take into consideration, as a part of the evidence in this ease, such failure of the collector to submit the goods under seizure to the judgment of the appraisers, to ascertain their true market value in Switzerland at the time of their exportation therefrom, and also to take into consideration, as a fact in this cause, that if the importers or their consignee had been dissatisfied with the value of the ribbons fixed by the local appraisers, the former would have been entitled to a reappraisement made 1106by an official appraiser familiar with the character, quality, and value of the goods.

I am also requested to charge the fourth proposition, which I do not charge. The substance of it is, that the jury are entitled to take into consideration, as facts in this cause, that if the ribbons under seizure had been appraised by the official appraisers of the government, as the law requires, and the appraised value had exceeded by the amount of as much as ten per cent, the value thus declared on entry, then, in addition to the regular duty of sixty per cent, on the appraised value, the law required the collector to levy an additional duty of twenty per cent on such appraised value; and, also, that there is no evidence that the government ever levied or exacted duty on the theory of valuation set up by it in this suit, but, having all the property in its hands, delivered it to the importers without any such exaction, and on the theory that the invoice valuation was correct.

I am also requested to charge you the fifth proposition, which I do not charge. The substance of it is that, as all the invoices produced by the government, from Frey, Thurneyson & Christ, of importations made prior to the goods under seizure, were reported by the official appraiser at the customhouse the collector to be correct, the jury are entitled, and it is their duty, to take that fact into consideration, especially if they shall find that the collector refused or failed to submit the sixteen cases of ribbons under seizure to the judgment of the appraisers as to the foreign market value thereof.

What I have to say on the subject of the second, third, fourth, and fifth requests is this: You have a right to take into consideration, as part of the evidence in this case on the subject of market value, the declaration before the consul, the certificate of the consul, everything that appears on the invoices and the entries, all the evidence that has been given in explanation of what appears on the faces of the invoices and entries, the fact that the duty was paid at the invoice valuations, and the fact that there appears to have been no raising by appraisement of any of the invoice valuations,—all these facts in reference not only to the invoices of the goods in suit, but to all the invoices put in evidence. But, upon that subject, I must give you some further instructions, in order to show you precisely the effect of these declarations, certificates of consuls, entries at the customhouse, and raising or not raising of invoice valuations on appraisement in a case of seizure of goods for fraud. The appraisement and reappraisement of goods is for the purpose of getting at the duty, and for no other object. It is a mode of litigation between the parties,—the government, on the one side, and the importer, on the other,—to find out how much duty is to be paid-on the goods; and, when that machinery is gone through with, by appraisement and reappraisement, and the duties are paid, and the merchandise is delivered, that transaction is settled, so far as the duties are concerned, and the government afterwards, even though it finds that there has been a mistake, cannot recover from any one, by a lien on the goods or by a suit against the individual, any more duty. It is conclusive upon that subject, but only upon that subject. It is not conclusive if a fraud has been committed. It does not condone or pardon any fraud that has been committed by any false invoice, or any knowing, intentional, wilful undervaluation. A forfeiture for fraud can be enforced after appraisement, reappraisement, payment of duty, and delivery of the goods. The appraisement system is for all cases, and ordinarily presupposes an honest invoice, but a mistaken one, and a payment of too little duty.

This subject came up before the same learned judge (Judge Hopkinson) in the case to which I have already referred (U. S. v. Twenty-Five Cases of Cloths), on a seizure of twenty-five cases of cloths. His remarks on it were these, and I give them to you as part of my instructions: “To invoice the goods below their actual value and cost, and to enter them by that invoice, with design to evade the duties, is, per se, an offence which forfeits them, whether the invoice was afterward instrumental in the estimation of the duties for that purpose or not.” So, in this ease, the offence was completed, if there was any offence, when the entry was made, because the offence consisted in making the entry; and whether the invoice, if it was in false one, was used as an instrument to estimate the duties, is of no consequence with reference to the offence, because the offence was completed before any such use was made of the invoice. “The evidence must follow the issue, and must depend upon the facts to be proved. When the question is, whether an importer has paid the duties legally chargeable upon his goods“—and that is not the question in a case of seizure—“it may be enough for him to say, ‘I have paid all that the officers of the government appointed to ascertain them declared to be due,’ and the question should rest. But when the inquiry is, whether he has been guilty of a specific fraud or not, it would be extraordinary if the acts or opinions of men in reference to another subject should be conclusive, either for his condemnation or acquittal.” In that case it was pressed upon the court that the goods had been appraised at the invoice prices. Such fact amounted to no more than the utmost effect that can be given to what appears, in this case, on the face of the invoices, because nothing more can be inferred in this case than that there was in fact an appraisement at the invoice prices. The judge says: “It is contended that, as these goods were appraised at the customhouse in New York at the invoice prices, that, as they were passed through that customhouse on 1107that appraisement, paid the duties according to that appraisement, and were thereupon delivered to the importers, they are now exempted from all further inquiry into their cost or value, not only in relation to the amount of duties legally chargeable on them, but on a prosecution for fraud in making up those invoices, and on any or every other account, that the very fraud by which it is alleged, in this prosecution, the passing of the goods through the customhouse was obtained,—that is, the false Invoices,—cannot now be inquired into. I can by no means assent to this doctrine, which, in my judgment, would be to offer a premium for successful fraud, and punishment only to the un skilful. I ad here, on reflection, to the opinion I gave on the trial. I will add but a remark. It is said these officers are the appointed agents of the government, and that the government is bound by their acts. The answer is plain. The government does not claim any right or privilege for itself that every citizen does not possess. Suppose one of you should appoint an agent to sell your house or goods, with even more clear and full powers than those given to the appraiser by the acts of congress. Your agent makes a sale, but it is afterward proved that he has been grossly defrauded by the purchaser, by false representation, by the suppression of the truth, by that which constitutes fraud in the law. Would you suppose you are bound by such a transaction—that the cheat is safe, and may retain your property only by saying that it was delivered to him by your agent?”

It has not been contended by the counsel for the claimants in this case, who have had too much experience in this class of cases to advance any such proposition, that the doctrine thus contended for before Judge Hopkinson, and which he declared not to be the law, is the law; and I have made these remarks on the subject only in order that you may see clearly the distinction between the questions involved in the mode of arriving at the duty, and the questions that arise on the seizure of goods.

I charge you in accordance with the sixth proposition: “The actual market value which the law required to be inserted in the invoices in suit was the fair and real worth in money of the ribbons described therein, at the time and in the country of manufacture, which was Switzerland, or, in other words, the sum which the manufacturer would have been willing to receive therefor, and persons familiar with the character and quality of the merchandise, and the condition of the market, and desiring to purchase, would have been willing to pay.” That is what I have already charged.

I decline to charge the seventh proposition: “The government assails the correctness of the valuation of the ribbons in the given invoices under seizure, and asserts that such invoices are false in respect to market value. It is, therefore, necessary for the government to satisfy the jury, beyond reasonable doubt, that there was an ascertainable market value of these identical ribbons, within the meaning of the law, and what that value was. The government must establish a standard of value in centimes or francs to which the invoices ought to have been conformed, before it can ask the jury to say that the inculpated invoices are false; and, if the government fails to establish such standard to the satisfaction of the jury, their verdict must be for the claimants.”

Then comes the eighth proposition, in reference to which I shall be obliged to make some remarks: “The market value to which the law required Messrs. Frey, Thurneyson & Christ to conform the invoices now on trial is to be predicated of the markets in Switzerland, not in the United States. Prices anywhere except in Switzerland are to be disregarded by the jury; and, therefore, prices which the consignors in Basle either urged or directed their consignees to realize in New York, with or without deducting all expenses, are as irrelevant and impertinent to the issue the jury are to try as would be prices for which the seized ribbons actually sold in this city. It is not the price at which these manufacturers held their ribbons for sale in New York, the prices at which, taking into consideration all the incidents and risks of the adventure, the ribbons stood them in New York, the prices at which they freely offered them in the market of New York, the prices they were willing to receive for them if sold in the ordinary course of trade in New York, but it is to Switzerland alone the law looks in respect to all these things, and, therefore, such valuations put upon their property when in New York are utterly foreign to the issue now to be submitted to the jury.” These propositions are true to a certain extent Undoubtedly, the selling price in New York, the value in New York, has nothing to do with this question, as you have seen in the course of the trial; and the evidence derived from the letters of Frey, Thurneyson & Christ, as to what they said the goods cost them, laid down in New York, is of no value or weight in this case, except so far as it is evidence of cost in Basle, to contradict other evidence given in regard to cost in Basle. The government has produced the letters as the statements of Prey, Thurneyson & Christ, as to what certain goods cost them delivered in New York; and you have heard the testimony of Viollier, whereby, after making certain deductions from such cost, he arrives at what the government claims was the cost in Switzerland, and a cost higher than that contained in invoices made up on the basis of cost, with five per cent, addition, and which the manufacturers stated to be the true market value at the time. It is only in that aspect that such evidence is of any value whatever, and it is only of consequence upon the question of intent, because it has no bearing except upon the valuations contained in invoices 1108voices that were made long prior to the invoices in suit. Prices in New York are of no consequence whatever as evidence of market value in Basle, except in reference to that particular branch of the ease of which I have Just spoken.

I charge you in accordance with the ninth proposition: “The government does not claim that the invoices of the ribbons under seizure are false in any other respect than their value in Switzerland, and, therefore, the provision of the act of March 3, 1863, which forfeits merchandise entered at the customhouse by a consignee, on an invoice which he thinks false in that particular, does not relieve the government from the obligation of establishing, to the satisfaction of the jury, what was the real worth of the property, in the sense of a fair buying and selling value, at the time and place of its production. The intelligent or unintelligent, the honest or dishonest, opinion which a consignee may entertain of the real foreign value of the property he enters at the customhouse in behalf of its foreign owner, cannot work a forfeiture thereof, in the face of countervailing evidence as to its value abroad.”

The tenth proposition is correct: “If the jury find the market value of the ribbons under seizure to be set forth in the invoice, then it is of no consequence what prices were given by Messrs. Frey, Thurneyson & Christ to Viollier, or, twenty days after, to Jones. The law of the United States, in this particular, takes no cognizance of fictitious prices, which, in the opinion of the jury, are different from the fair market value, as determined by real transactions of trade and business. A foreign manufacturer, sending his merchandise to the United States, is entitled to give to strangers or other persons whatever prices therefor he pleases, provided he places in his customhouse invoices its value in the actual markets of the country of production.”

I charge you in accordance with the eleventh proposition: “If the jury shall find that the invoice prices of the ribbons under seizure are as much as they were worth or would have brought if offered for sale in the markets of Switzerland, at the time of the manufacture of the ribbons was complete, then it is of no consequence what was the actual cost of manufacturing the merchandise, or what Messrs. Prey, Thurneyson & Christ may have told Thomass or his firm was its cost, or how the manufacturers arrived at the prices stated in the invoices.”

I charge you in accordance with the twelfth proposition: “The invoices and entries of ribbons imported by Messrs. Prey, Thurneyson & Christ, prior to the sixteen cases under seizure, are not admitted in evidence as showing or tending to show the market value of the said sixteen cases, but are permitted to go to the jury solely in relation to the intent with which the seized ribbons, now proceeded against, were undervalued, provided the jury shall come to the conclusion that such undervaluation exists. The jury must find undervaluation of the sixteen cases before they can take said prior importations into consideration.” That is true, and I have already so charged you.

The thirteenth proposition is correct: “The invoices and entries of importations prior to those of the ribbons now proceeded against are not entitled to consideration by the jury in respect to the intent with which the invoices under seizure were made up, until the jury are satisfied, by evidence in the cause, of the actual market value of the ribbons contained in the first-named invoices and entries, at the time and place of their manufacture, and that such invoice valuations were knowingly or fraudulently made by Messrs. Prey, Thurneyson & Christ at less than said fair market value. To entitle the prior invoices to consideration on the question of intent, as before mentioned, the jury must be as well satisfied that such invoices were knowingly undervalued as they must be that the invoices now proceeded against were knowingly undervalued before they can find a verdict for the United States.” That is true, and I have already so stated.

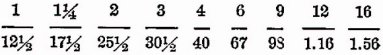

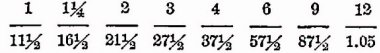

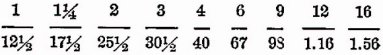

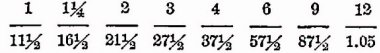

I charge you in accordance with the fourteenth proposition: “Among the methods of ascertaining the true interpretation to be put on the letter of Messrs. Prey, Thurneyson & Christ to Messrs Lefman, Kiefer & Thomass, dated Basle, July 1, 1862, in respect to the following prices named therein, to wit:

No.  the description of currency referred to in such figures, and the general character and purpose of the valuations therein, the jury are entitled to take into consideration the price at which the ribbons contained in the invoice, dated July 11, 1862, and in the accounts sales of June 30, and July 8, 1862, were sold in currency or greenbacks, in New York, as follows, to wit:

the description of currency referred to in such figures, and the general character and purpose of the valuations therein, the jury are entitled to take into consideration the price at which the ribbons contained in the invoice, dated July 11, 1862, and in the accounts sales of June 30, and July 8, 1862, were sold in currency or greenbacks, in New York, as follows, to wit:

No.  —with sales at auction at very much less prices.”

—with sales at auction at very much less prices.”

I also charge in accordance with the fifteenth proposition: “In determining the actual market value of the ribbons under seizure at the time and place of their manufacture, or of the ribbons of prior importations, given in evidence in this cause, the jury are not entitled to take into consideration the price at which their owner held or holds them for sale, or freely offers them for sale, or which he is willing to receive for them, if they are sold in the market of New York.”

I charge you in accordance with the sixteenth proposition: “The witness Thomass having sworn on the trial that, for a series of years prior to and including the early 1109part of the year 1866, he had repeatedly committed the offence of perjury under the law of the United States (Act March 3, 1825, § 13, 4 Stat. 118), by swearing falsely to the truth of invoices produced by him at the customhouse, and, having also sworn on behalf of the government, on this trial, that the, said invoices so produced were false as to the market value therein, and that he then knew them to be thus false, and the last-named testimony of the witness Thomass being in direct contradiction in relation to the same transaction to the oaths made by him at the customhouse, it is not entitled to credit, and ought not to be regarded by the jury unless supported by other evidence to the same point”

The seventeenth proposition I decline to charge: “In respect to the contents of letters asserted by the witness Thomass to have been destroyed, his evidence is unsupported by any other testimony, and, therefore, ought to be and must be disregarded by the jury.” That proposition I refuse to charge, because it is a matter of fact, and one for your consideration solely.

There is but one other point to which it is necessary I should call your attention, and that relates to the burden of proof. The law on that subject has been the law since the year 1799, and was affirmed by the supreme court no longer ago than in December, 1865, in the Case of Clicquot's Champagne, to which I have already referred, where the court say: “It is argued that the rule relating to probable cause and the onus probandi, prescribed in the seventy-first section of the act of 1799, is confined to prosecutions under that act, and has no application to those under the act of 1863, which is silent upon the subject. It would be a singular result, if in a prosecution upon an information containing counts upon this and later statutes in pari materia, the rule should apply to a part of the counts and not to others. The seventieth and seventy-first sections must be construed together. They both look to future and further legislation. In all the changes which the revenue laws have undergone, neither has been repealed. The authority to seize out of the district of the seizing officer, and this rule of onus probandi, have always been regarded as permanent features of the revenue system of the country.” And they affirm the charge of the district judge, and his refusal to charge as requested by the claimants in that ease, that the burden of proof was not upon the claimants, but was upon the prosecution. Now, the law upon that subject is this—that where probable cause is shown for the prosecution—and in this case, and in all cases, it is for the court to decide whether probable cause is shown for the prosecution, and the court decides that there is such probable cause by throwing the claimants upon their defence, as it did in this case—where probable cause is shown for the prosecution, the burden of proof is thrown upon the claimants to dispel the suspicion, and to explain the circumstances which seem to render it probable there has been a knowing undervaluation. The government in this ease, having established probable cause, it is for the claimants to show their innocence, and dispel and clear up the suspicion which the government in the beginning raised against them. Under this rule it is for you to say whether the claimants have made out their defence, and have shown that these ribbons were invoiced at a value as high as their actual market value in Basle, at the time they were manufactured, or that the failure so to invoice them was the result of accident or mistake, and not of knowledge or intent. The actual undervaluation must be found by you as a matter of fact in this case, in order to warrant a verdict for the United States. If there was no undervaluation, your verdict will be for the claimants. If there was an undervaluation, you will then proceed to the next question which is whether there was any knowledge on the part either of the manufacturers and consignors in Switzerland, or of their agent here, who entered the goods at the customhouse, that there was such undervaluation. You must find that fact also in favor of the United States, in order to find a verdict for the United States; because, it may happen in some cases, that there may be an undervaluation and yet not a knowing undervaluation. You must find that there was not only an undervaluation, but a knowing undervaluation, on the part of the consignors or the consignees, before you can find in favor of the government; and, if you find either that there was not an undervaluation, or, if there was, that there was no knowledge of it, but it was made by accident or mistake, and not by design, on the part either of the senders of the goods or of their consignees here, you will find for the claimants.

This case being one of so great importance to the parties interested, and to the public, no apology is needed for the time I have occupied in presenting it to you. I have desired that you should have a full and clear view of every question connected with it which could possibly come up in the course of your discussions, and of the application of the evidence to the law, and I now commit it to you, satisfied that you will bestow upon its decision the same attention and patience which you have manifested throughout the trial.

The jury found a verdict for the claimants.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.

the description of currency referred to in such figures, and the general character and purpose of the valuations therein, the jury are entitled to take into consideration the price at which the ribbons contained in the invoice, dated July 11, 1862, and in the accounts sales of June 30, and July 8, 1862, were sold in currency or greenbacks, in New York, as follows, to wit:

the description of currency referred to in such figures, and the general character and purpose of the valuations therein, the jury are entitled to take into consideration the price at which the ribbons contained in the invoice, dated July 11, 1862, and in the accounts sales of June 30, and July 8, 1862, were sold in currency or greenbacks, in New York, as follows, to wit: —with sales at auction at very much less prices.”

—with sales at auction at very much less prices.”