Case No. 14,392.

UNION PAPER-BAG MACH. CO. et al. v. PULTZ & WALKLEY CO. et al.

[15 Blatchf. 160; 3 Ban. & A. 403: 15 O. G. 423; Merw. Pat. Inv. 678.]1

Circuit Court, D. Connecticut.

Aug. 20, 1878.

PATENTS—PRIOR EXPERIMENTS—SPECIFICATIONS—PAPER BAG MACHINE.

1. The first claim of the letters patent granted to William Goodale, July 12th, 1859, for improvements in machinery for making paper bags, and extended for 7 years from July 12th, 1873, namely: “Making the cutter which cuts the paper from the roll or niece, of the form herein described, that, on cutting off the paper, it also cuts it into the required form to fold into a bag, without further cutting,” is valid.

2. Knowledge of prior experiments by another, will not defeat the claim of the patentee to an invention, if it appears that, after those experiments wire abandoned, he first perfected and adapted the invention to actual use.

3. The patentee has the right to take up the improvement at the point where it was left by his predecessor and if, by the exercise of his own inventive skill, he is successful in first perfecting and reducing to practice the invention which his predecessor undertook to make, he is 666entitled to the merit of such improvement, as an original inventor.

[Cited in Whittlesey v. Ames, 13 Fed. 899.]

4. Declarations of a patentee and former owner of a patent, undertaking to restrict the invention within a narrower compass than that stated in his specification, will not be allowed to vary the construction which would otherwise be given to the patent

5. The invention of Goodale was not simply a knife which would cut without waste, or which would produce the exact form of blank described in the specification, but was a machine having a cutter of five planes, which, by a transverse cut across a roll of paper in the flat sheet, cut the paper into the required form to fold into a paper bag without further cutting out, the form of the blank being substantially the form given in the specification.

6. A machine having a knife of the irregular form of the Goodale cutter, which cuts the paper into the required form to fold into a bag, without further cutting out, is an infringement of the first claim of the Goodale patent, although such knife has an additional parallel blade at each end of it.

7. Nor does the removal of the central cutting portion of such knife about a bag's length in advance of the side cutters, cause the machine to be no infringement, the cutters which remove side pieces of pancr from the roll remaining the same.

8. It required invention to make a knife which would cut from a roll of paper in the fiat sheet, by one cut, a blank which could be folded into a bag without further cutting out.

In equity.

George Harding, for plaintiffs.

Charles E. Mitchell and Benjamin F. Thurston, for defendants.

SHIPMAN, District Judge. This is a bill in equity founded upon the alleged infringement by the defendants of the first claim of letters patent [No. 24,734], dated July 12th, 1859, which were granted to William Goodale, for improvements in machinery for making paper bags. Said letters patent were extended for the term of seven years from July 12th, 1873. The patentee, on July 14th, 1873, assigned all his interest in the patent to the Union Paper-Bag Machine Company. The other plaintiffs are the exclusive licensees of said assignees, to use the improvement within certain territory, including the state of Connecticut. The answer denies that the patentee was the original and first inventor of the alleged invention, and also denies that, upon any proper construction of the patent, the defendants have infringed, and avers that the patent was surreptitiously and unjustly obtained for that which was in fact invented by another, who was using reasonable diligence in adapting and perfecting the same, and that the alleged improvements were not the product of inventive ingenuity, but were due to mechanical skill merely.

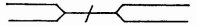

The specification says, that the invention which is the subject of the first claim consists “in making the cutter which cuts the paper from the roll or piece, of the peculiar irregular form hereinafter described, whereby it is caused, by the operation by which it cuts the paper from the roll or piece, to give it the form hereinafter specified, which permits it, without further cutting out, to be folded into a bag.” The form of the cutter will be understood by the following representation of the cut which is made in the paper:

By the stroke of the cutter, a projection is left in the centre of one end of the blank, which forms, when the side lips are folded together, a lap to cover the mouth of the bag. A depression is left in the centre of the other end of the blank. When the side lips of the blank are folded together, they lap over to make the seam down the middle of one side of the bag, and the two projections at the lower end of the side lips combine, when folded on the opposite side to the central seam, to form a lap and thus to make the bottom of the bag. The top flap is upon the seam side of the bag, and the bottom flaps are upon the reverse side. The first claim of the patent is for “making the cutter which cuts the paper from the roll or piece, of the form herein described, that, in cutting off the paper, it also cuts it to the required form to fold into a bag, without further cutting out.”

The cutter which was used by the defendants prior to the commencement of the suit was of the following form:

It appears, by a stipulation of the parties, that, afterwards, the “defendants employed cutting devices like those previously employed, so far as they removed side pieces of paper from the roll, and then severed the paper by a straight cutter near the end pasting device, and a bag's length in advance of the side cutters above referred to.”

The effect of either system of the defendants' cutters is to cut a projection at the centre of each end of the blank. When the two side lips are folded over to form a central seam down one side of the bag, the two end flaps are likewise folded over upon the same side, and form respectively the top and bottom of the bag, and thus all the seams are upon the same side. The Goodale cutter produces no waste. The paper which is severed between the two blades at the right and left extremities of the defendants' cutter is a waste piece of paper.

As in many other eases, the question of infringement depends much upon the construction which is given to the patent. The defendants insist that, properly construed, the first claim is for a knife having five planes, for producing the blank described in the patent without waste of material, that is to say, a blank in which the two lower ends of the side lips combine to form the bottom lap, or a blank having a projection at one end and a corresponding depression at the other end. 667 In order to ascertain the proper construction of the patent, it is important to know the nature and extent of the invention which was made by the patentee. Upon the question of novelty, the defendants have not relied upon any of the devices or patents which are mentioned in the answer, but they say, first, that William Goodale, the patentee, borrowed the invention from his brother, E. W. Goodale, who is not named in the answer, and, secondly, that, if the E. W. Goodale machine cannot be used as an anticipatory invention, to defeat the patent, it can properly be used to show the state of the art at the time of the William Goodale invention.

On July 25th, 1856, E. W. Goodale, the brother of the patentee, made an application for a patent for an improvement upon a bag machine which he had theretofore invented, which application was rejected. A small model, containing the alleged improvement, was sent to the patent office. This model contained the same form of cutter, the “three cutter method,” which is now used by the defendants. E. W. Goodale never constructed a machine of full size like his model, and never made or sold bags like those which could have been made upon such a machine. William Goodale worked for his brother from 1854 or 1855 to 1859 or 1860, and knew of the model and the invention which was specified in the rejected application, and testifies that his, William's, object in shaping his knife was to cut the paper without waste. E. W. Goodale purchased the William Goodale patent, and constructed machines like those described therein, and manufactured bags upon such machines. It does not appear that he ever undertook to perfect his model after the application was rejected. His idea was never reduced to practice, and was never embodied in an operative machine, and, upon the rejection of his application, he seems to have abandoned his inchoate invention, and afterwards to have manufactured bags under the subsequent patent of his brother. About a year after the rejection of the application, William Goodale first thought of attempting to construct a new machine.

Seasonable objection was made by the plaintiffs to the admission of this testimony, if it was offered to prove that the patentee was not the original inventor of the thing patented, upon the ground that neither the invention of E. W. Goodale, nor his use of the invention, nor his name, as one who had a prior knowledge of the thing patented, were mentioned in the answer. It has frequently and uniformly been held that such testimony is not admissible to show that the patentee was not the original inventor of the thing patented. Agawam Go. v. Jordan, 7 Wall. [74 U. S.] 583; Railroad Co. v. Dubois, 12 Wall. [79 U. S.] 47. But as the testimony is relied upon in order to affect the construction of the patent, it is necessary to state what it proves. The E. W. Goodale model was an experiment which rested in theory alone, and was never reduced to practice, or brought into use, and was abandoned by the alleged inventor. If an alleged prior invention “was only an experiment, and was never perfected or brought into actual use, but was abandoned and never revived by the alleged inventor, the mere fact of having unsuccessfully applied for a patent therefor cannot take the case out of the category of unsuccessful experiments.” The Corn-Planter Patent, 23 Wall. [90 U. S.] 181. It is, however, said, that William Goodale knew of this model and of this invention before he commenced his own experiments, and, therefore, was not an original and independent inventor. Knowledge of prior experiments by another will not defeat the claim of the patentee to, an invention, if it appears that, after those experiments” were abandoned, he first perfected and adapted the invention to actual use; but he will not be an original inventor, and his claim to originality will be defeated, if the knowledge or information which he derived from the abandoned models or experiments was sufficiently definite and clear to enable him to construct the improved thing which was the subject of his alleged invention. Washburn v. Gould [Case No. 17,214]; Judson v. Moore [Id 7,566]; Pitts v. Hall [Id. 11,192]. It is plain, that the cutter of William Goodale was, in its completed and perfected state, a simpler and more economical cutter than the one shown in the E. W. Goodale model. It proved that the patentee had exercised invention. Having attained success by such exercise and by his skill and ingenuity, he was entitled to the position of an original inventor, and he rightfully obtained a patent for his improvement.

Admitting this to be true, the defendants now ask what was his improvement, and they say that the model and the rejected application of E. W. Goodale, and the patentee's knowledge of his brother's invention, so far as it had progressed, are important facts showing the state of the art at the date of the patentee's indention, and showing that his actual invention was of a very limited character. Such facts are admissible to show the circumstances connected with the invention, and the state of things existing at the time, and thus to enable the court to understand the subject-matter of the patent, and to throw light upon its proper construction, and may be very important. The patentee is not, however, necessarily limited, in his patent, to the narrow field between the model of his predecessor and his own perfected machine, for his invention may have actually covered a wider field, and may have included the territory which the previous investigator undertook to occupy and abandoned. The patentee has the right to take up the improvement at the point where it was left by his predecessor, and it by the exercise of his own inventive skill, he is successful in first perfecting and reducing to practice the invention 668which his predecessor undertook to make, he is entitled to the merit of such improvement, as an original inventor. Whitely v. Swayne, 7 Wall. [74 U. S.] 685. And, if he is an original inventor of the improvement, he is entitled to the benefit of unsubstantial variations and modifications in form of the principle of his invention, notwithstanding such modifications may run into and include the forms of mechanism shown in the abandoned experiments of which he had knowledge, provided the invention is properly claimed and set forth in his specification.

To the testimony of the patentee that his object in shaping his knife “was to cut the paper without waste, without any reference or view to my brother's machine any way,” I do not give much weight, if the answer is construed to mean that his sole or main object was to cut the paper without waste. Undoubtedly, one object was to avoid waste; but the patentee, in his specification, gave a wider scope to his invention Nothing is said in the patent in regard to cutting the paper without waste. I am not willing to vary the construction which would otherwise be given to a patent, in order to conform to the declarations of a patentee and former owner, whereby he undertakes to restrict the invention within a narrower compass than that which he had previously stated in the specification.

Giving to the new testimony in regard to the state of the art its appropriate weight, I think that the invention of William Goodale was not simply a knife which would cut without waste, or which would produce the exact form of blank described in his specification, but that his place as an inventor is that which was stated in the opinion of the supreme court upon this patent. “Evidence of a satisfactory character is exhibited, to show that the assignor of the complainants was the first person to organize an operative machine to make paper bags from a roll of paper in the flat sheet, by a transverse cut across the same with a knife having five planes, so that the blanks, so called, when cut and folded, will present a paper bag of the form and description given in the specification and drawings of the patent.” Union Paper-Bag Mach. Co. r. Murphy. 97 U. S. 120. The thing invented was an organized machine, having a cutter of five planes, which, by a transverse cut across a roll of paper in the flat sheet, cut the paper into the required form to fold into a paper bag without further cutting out, the form of the blank being substantially the form given in the specification. The form of the knife must be substantially “the peculiar irregular form” which was described. It must have the specified effect, that is, it must cut the paper into the form substantially specified, so as to be folded into a bag without further cutting out. The exact form of the Goodale blank when it was cut, and before it was folded, was not of the essence of the invention, provided it could be folded, without further cutting out, into a paper bag of the ordinary form; otherwise, the patentee, who was the pioneer in the art of making paper bags from a roll of paper in the flat sheet, by a transverse cut across the same with a knife having five planes, had limited himself not only to a knife of the peculiar irregular form, but to a knife which should produce a blank of the precise shape, before folding, which his knife produced.

Neither did the patentee confine himself to a form of knife which should cut without waste. If another person should use a knife so near to the form of the patented knife as to embody its mode of operation, and to produce the same result of cutting a blank from a flat roll, so that it could be folded without further cutting out, he would be an infringer, notwithstanding his knife did not accomplish the work to as good advantage as did the patented invention. “The patentee having described his invention, and shown its principles, and claimed it in that form which most perfectly embodies it, is, in contemplation of law, deemed to claim every form in which his invention may be copied, unless he manifests an intention to disclaim some of those forms.” Winans v. Denmead, 15 How. [56 U. S.] 330.

The defendant's knife has the five planes of the Goodale knife, with an additional parallel blade at each end of the cutter. The effect of these two parallel blades is to inane the same projection at the top of the blank which the Goodale knife makes, but, by cutting out a waste piece of paper, to make, also, a projection at the other end of the blank, which forms the bottom flap; whereas, the Goodale knife makes a depression, and the two end lips are turned over to make the bottom of the bag. The substance of the invention, the irregular form of the Goodale cutter, which cuts the paper into the required form to fold into a bag, without further cutting out, is found in the defendants' knife. The office which is performed by the cutter in such machine is substantially the same, and the variations in form or in function do not vary the principle of either cutter. If the E. W. Goodale knife had been the first perfected invention, the William Goodale knife, which omitted a parallel blade, and thereby effected a small saving in stock, would have been a patentable improvement, but would have been subsidiary to the original invention. The defendants' cutter, by cutting out a projection on each end of the blank, produces a bag which has a neater appearance than its rival has, but the work is done in substantially the same way and by substantially the same means, and the result is substantially the same.

Stress is laid upon the argument, that the Goodale machine is organized, in all its parts, with reference to the fact that the cutter is one which makes a projection at the top and 669an excavation at the bottom of the blank, and thus the fold of the bottom of the bag is upon the reverse side from the fold of the top. This is true, but this fact does not establish the defendants' position, that the essence of the Goodale invention was the exact form of his cutter. He had made a decided advance in the art, and his invention gave him a right to claim a cutter of substantially the form which he invented, notwithstanding the fact that the other parts of his machine, which turned and pasted the bottom flaps, were arranged with reference to the peculiar form of his blank. The defendants do not escape from the charge of infringement by the fact that, in order to accomplish the results attained by parts of the plaintiffs' machine other than the cutter, those parts had to be modified in order to meet the change which they made in the form of the cutter.

The defendants next insist that their “three cutter method” is not within the patent, even if the knife which they used at the commencement of the suit is an infringement. After a preliminary injunction had restrained them from the use of the knife as originally constructed, the defendants moved the central cutting portion of the knife about a bag's length in advance of the side cutters. This was a mere change of position, and was not a change of substance, and produced no new result.

It is not necessary to consider the defence, that the patentee surreptitiously and unjustly obtained the patent for that which was in fact invented by E. W. Goodale, as there is no evidence that he was using any effort to adapt and perfect his invention, and he had in fact given up all attempts to perfect it before the patentee took up the subject of the improvement.

The remaining defence is, that there was no invention in the cutter, but that the improvement was an exercise of mechanical skill only. The history of the art of paper bag manufacture, and of the various patents which have been granted for paper bag machines, shows that this is a theoretical defence. As a matter of fact, there was invention. The inventor was required to make a knife which should cut from a roll of paper in the flat sheet, by one cut, a “blank which could be folded into a bag without further cutting out That had not been done before, although paper bag machines are old, and have “been constructed by many persons and in various forms for more than twenty years, and with more or less utility.” Machine Co. v. Murphy, cited supra.

There should be a decree for an injunction and an accounting in respect to the first claim.

[The above decision was confirmed in Case No. 14,393 For another ease involving this patent, see Union Paper-Bag Mach. Co. v. Murphy, 97 U. S. 120.]

1 [Reported by Hon. Samuel Blatchford, Circuit Judge; reprinted in 3 Ban. & A. 403; and here republished by permission. Merw. Pat Inv. 678, contains only a partial report]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.