Case No. 14,390.

UNION PAPER-BAG MACH. CO. et al. v. NEWELL et al.

[11 Blatchf. 379; 6 Fish Pat Cas. 582; 5 O. G. 173.]1

Circuit Court, S. D. New York.

Nov. 26, 1873.

PATENTS—PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION—MACHINE FOR MAKING PAPER BAGS—SIDE CUTTERS.

1. The first claim of the letters patent granted September 12th, 1865, to Benjamin S. Binney, assignee of E. W. Goodale, for “a machine for making paper bags,” is in these words: “Making the side cutters, B, with curved ends, substantially as, and for the purpose, set forth.” Such claim covers side cutters which have a regular curve near their inner ends, although the specification speaks of the curve near the inner ends of the patented side cutters as being an irregular curve, it not appearing that any side cutter with a curved inner end, for the same purpose, existed before.

2. The repeal, by the 111th section of the act of July 8, 1870 (16 Stat. 216), of the act of July 4, 1836 (5 Stat. 117). did not have the effect to vacate patents granted under the said act of 1836, nor does it have the effect to prevent the maintaining of suits on such patents for causes of action accruing after the passage of said act of 1870.

In equity.

[Motion for preliminary injunction. Suit brought [against George L. Newell and George H. Mallary] on letters patent [No. 49,951] granted Benjamin S. Binney, assignee of E. W. Goodale. September 12, 1865, for “machine for making paper bags,” and afterward assigned to complainants.]2

George Harding and Fisher & Duncan, for plaintiffs.

Marcus P. Norton, for defendants.

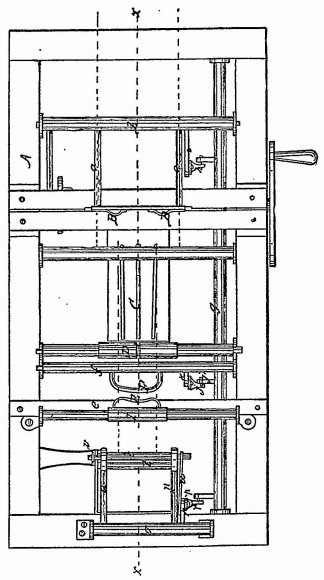

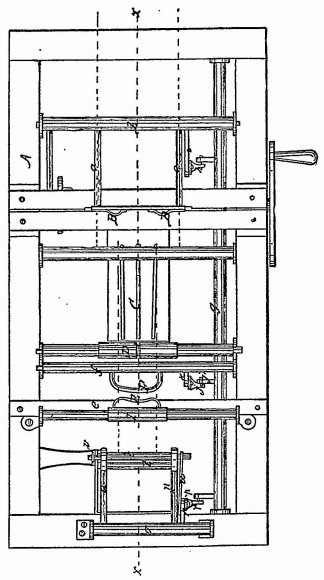

BLATCHFORD District Judge. This is an application for a preliminary injunction to restrain the defendants from infringing letters patent granted, September 12th, 1865, to Benjamin S. Binney, assignee of E. W. Goodale, the inventor, for a “machine for making paper bags.” As the claim of infringement, on this application, is confined to the first claim of the patent, only such parts of the specification need be referred to as relate to that claim. The specification says: “This invention consists, first, in giving to the side cutters an irregular curve at or near their inside ends, in such a manner that the form of the paper cut by their action, and the corners produced by folding said paper, are of such a shape that the paste shall come upon the paper where it is single, and thus be enabled to hold better than it does when it is applied in the ordinary way. It designates as inside cutters” the cutters “which serve to cut the paper so that the sides may fold and make the seam in the centre of the bag.” It says, that “these cutters or knives are bent in an irregular curve near their inner ends, so that the paper cut by their action, and the corners produced by folding said paper, are such that the paste shall come upon the paper where it is single, and that it will hold better than it does when applied to the paper in the usual manner.” One of the figures in the drawings contains lines which are said, by the specification, to designate the cuts made by the side cutters. The first claim is in these words: “Making the side cutters, B, with curved ends, substantially as, and for the purpose, set forth.”

In the defendants' machine there are cutters which serve to cut the paper so that the sides may fold and make the seam in the centre of the bag. They are side cutters. They make a cut of a definite length from the outside edge of the paper inwards towards the centre, so as to leave flaps or side pieces, which are then to be folded over from each side towards the centre, overlapping each other at the centre, and making a seam in the centre. The defendants' side cutters are not straight or unbent in their whole length nor are they bent at an angle near their inner ends; but they are bent in a curve near their inner ends. The effect of this curve is, that, when the side pieces are folded over, the central end piece, of a single thickness of paper, may be pasted down without folding over, in addition to such single thickness, any part of the double thickness formed by folding the side pieces, and yet the corners will be perfectly close and tight. This result is due to the curve near the inner ends of the side cutters, in contradistinction to an angle there. Where the cutters have an angle there, and the central end piece, of a single thickness, is pasted down, without folding over, in addition, any part of the double thickness, there are holes or openings at the corners, and, to make tight corners, it is necessary to fold down part of the double thickness, and then the paste can only come upon the inner one of the two thicknesses, while the outer one, not being held to the inner one, tends to draw the inner one away from the surface to which it is pasted. This is precisely what is done by the patentee's arrangement, and what he describes, in the specification, as the result of his arrangement, when he says, that the form of the paper cut by the curved side cutters, and the corners produced by folding said paper, are of such a shape that the paste shall come upon the paper where it is single, and thus will hold better than when applied to the paper in the usual way. The language of the specification is not very artistic, and the idea sought to be conveyed is not as well expressed as it might be, but the meaning cannot be mistaken, when read in view of the state of the art, by a person skilled therein

It is to be noted, that the body of the

661[Drawings of patent No. 49,951, granted Septemper 12, 1865, to E. W. Goodale; published from the records of the United States patent office.]

specification speaks of the curve near the inner ends of the side cutters as being an irregular curve, and that the claim drops the word “irregular,” and claims making the side cutters “with curved ends, substantially as, and for the purpose, set forth.” It is contended by the defendants, that the drawing of the patent shows the cut made by the side cutters as being, for its whole length, of a form of curve which may properly be called irregular, as a whole, and that the defendants' side cutter is straight for most of its length, and of a regular curve near its inner end. But this is immaterial. It is not shown that any side cutter with a curved inner end, for the same purpose, existed before. That being so, any degree of curve to the inner end of the cutter, which will produce the result described, is within the claim, and must be regarded as an irregular curve, whatever the word “irregular” may mean. Nothing but a curve will produce the effect. An angle will not. The patentee was the first to use the curve. The form of curve represented in his drawings will produce the effect. His claim speaks merely of “curved” ends. Hence, any curved end which will produce the result is his curved end.

It is contended, for the defendants, that, as the patent sued on was issued under the authority of the act of July 4, 1836 (5 Stat 117), and as that act is repealed by the 111th section of the act of July 8, 1870 (16 Stat. 216), such repeal vacated and made void the said patent; and that, if this is not so, yet no suit can be maintained upon said patent, for any cause of action which accrued after the 8th of July, 1870, as did the cause of action in this suit. The 111th 662section of the act of 1870, which repeals the act of 1836, contains the proviso, that “the repeal hereby enacted shall not affect, impair or take away any right existing under” the repealed act, “but all actions and causes of action, both in law and in equity, which have arisen under” said act, “may be commenced and prosecuted, and, if already commenced, may be prosecuted to final judgment and execution, in the same manner as though this act had not been passed, excepting that the remedial provisions of this act shall be applicable to all suits and proceedings hereafter commenced.”

The rights created by, and arising under, a patent granted under the act of 1830, are rights existing under that act. The proviso declares that the repeal of that act shall not affect, impair or take away such rights. A right granted by the patent in suit is the exclusive right to make and use and vend to others to be used the inventions claimed in the patent. Such right was a right existing under the act of 1836, on the 8th of July, 1870. The right to sue, after the latter date, for infringements of the patent committed after that date, may, in one sense, be said not to have been a right existing on the 8th of July, 1870, because the cause of action had not then arisen. But the grant held under the patent was a right, and a vested right. Such grant it was intended should continue till it should expire by its limitation. This is apparent from the provisions of the 63d, 64th, 65th and 66th sections of the act of 1870, which enact that patents granted prior to March 2d, 1801, (and which were patents for fourteen years,) may be extended for seven years beyond the original terms of their limitation.

It is further urged, that the wording of the proviso to the 111th section of the act of 1870 is such, that the only right saved is the right to prosecute actions and causes of action which arose prior to July 8th, 1870, on patents theretofore granted. No reason is assigned why, if such prosecutions are allowed, they should not also be allowed in respect of causes of action arising on or after July 8th, 1870, on such patents. But the point taken is rested solely on the fact, that the enactment in reference to prosecutions is introduced by the word “but;” and it is maintained that the effect of the use of that word is, that the rights declared, in the preceding part of the proviso, to be not affected, are limited to the actions and causes of action afterwards specified, that is, to such as arose before July 8th, 1870. No such effect, however, can properly be given to the use of the word “but” The first part of the proviso, as already stated, has the effect to keep in life the patent and its grant. But, actions had been brought and were pending on existing patents, and causes of action had arisen on existing patents, which had not been sued on, and the provisions of all prior existing acts in regard to suits on patents were being repealed. Hence, the necessity of providing that such actions and causes of action might be prosecuted in the same manner as though the act of 1870 had not been passed. But, the proviso goes on to declare, that the remedial provisions of the act of 1870 shall apply to all suits thereafter commenced for causes of action existing on the 8th of July, 1870, under patents previously granted. It leaves existing suits to be conducted according to the remedial provisions prescribed by the prior acts. There remain, however, suits to be brought on causes of action arising on or after July 8th, 1870, on patents theretofore granted. The proviso does not apply to the manner of conducting such suits. The existing patents, and the grants of right in them, being saved by the proviso, a reference to prior sections of the act shows that those sections apply to then existing patents, and to suits to be brought thereon for causes of action to arise on or after July 8th, 1870, as well as to patents to be issued under the act of 1870 and to suits to be brought thereon. Thus, the 53d section, in regard to reissues, embraces reissues of existing patents. If not, as all prior acts are repealed, there could be no reissues of such patents. The same is true of the 54th section, in regard to disclaimers, and of sections 55, 56, 58, 59, 60, 61, and 62, in regard to suits. Full authority is given by the latter sections, for bringing this suit.

As to the alleged license set up by the defendants, it was fully considered and passed upon in a former suit in this court between the parties to this suit, where it was held, on final hearing, that such license had no valid existence as a license,” in the hands of these defendants, as against the Union Paper-Bag Machine Company, and persons holding under them.

Nothing is shown to affect the novelty of the first claim of the patent sued on, the infringement is clear, and the case, on all points, is one entirely free from doubt. The injunction asked for must, therefore, be granted.

[Subsequently, the defendants made an application to the court, on affidavits, to dissolve the injunction. The motion was denied. Case No. 14,389.]

1 [Reported by Hon Samuel Blatchford, District Judge, and by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here compiled and reprinted by permission. The syllabus and opinion are from 11 Blatchf. 379, and the statement is from 6 Fish. Pat. Cas. 582.]

2 [From 0 Fish. Pat. Cas. 582]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.