Case No. 14,387.

UNION PAPER-BAG MACH. CO. et al. v. BINNEY.

[5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 166.]1

Circuit Court, D. Massachusetts.

Nov., 1871.

PATENTS—PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION—AFFIDAVITS—INFRINGEMENT—DEFENCE.

1. A preliminary injunction in patent cases ought not to be granted where there are new and difficult questions to be decided, or where there is anything in the position or relations of the parties which would cause it to operate unjustly.

2. A delay of three months in filing a bill, after the infringement was ascertained, is no ground for refusing an injunction.

3. The plaintiff must not strengthen his case, on the question of infringement, by rebutting affidavits. There would be great danger of surprise if he were permitted to do this under the guise of a reply.

4. A defendant who denies access to his machine, and who does not, at the hearing, produce his machine, nor any model or drawing of it, nor the product which it manufactures, nor rely upon the patent under which it is constructed; but who contents himself with attacking the plaintiff's model, denying that it can be a true copy of his machine, and with pointing out certain discrepancies in it, must not expect that doubtful points will be construed favorably to him.

5. A defendant can not relieve himself from the charge of infringement by showing that while he uses substantially the same devices, they operate less perfectly in his machine than in the plaintiff's.

Motion for provisional injunction. Suit brought [against Benjamin S. Binney] upon letters patent [No. 30,191], for “improvement in paper-bag machinery,” granted to Horatio G. Armstrong, October 2, 1860, and assigned to complainants; and also letters patent [No. 38,452], for “improvement in paper-bag machines,” granted to complainants as assignees of Simon E. Pettee, May 5, 1863.

654

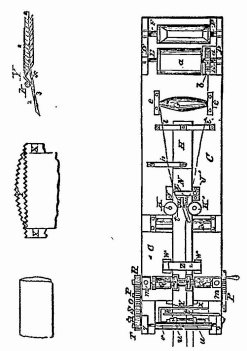

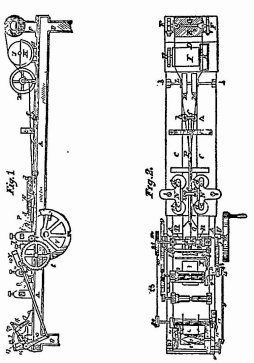

The above engraving represents a plan view of the Armstrong machine. The paper passed from the roll, a, under the shaping-roller, G, by which it was partially folded, to the bar, N, between the guide-blocks, J, J, and rollers, K, K', which completed the formation of the tube. The edges of the horizontal lap having been pasted together, the tube was cut off in suitable lengths for single bags by a striker, k, which struck the paper sharply against two knives with seriated edges, so that, when severed, one side projected over the other, and thus formed the top and bottom lap of the bag.

The claims of the patent were as follows: (1) The employment, for severing the folded paper, of the upper and lower knives, with their edges, X and Y, arranged in respect to each other, substantially as set forth, in combination with the revolving striker k, or its equivalent. (2) In combination with the said knives and striker, I claim the rollers, U and V, for retaining the end of the folded paper during the operation of the striker. (3) The roller, Q, Q', in combination with the blade, N, the upper roller having one or more collars n, n, so arranged in respect to openings in the blade that the action of the rollers on the folded paper cannot interfere with the said blade, as set forth. (4) The horizontal rollers, K, K, and the guide-blocks, J, J', arranged in respect to each other and to the blade, N, substantially as and for the purpose set forth. (5) The plate, L, with its projections l and l“, or their equivalents, arranged and operating as set forth, for the purpose specified. (6) Causing one edge of the paper to traverse in contact with a ratchet or notched wheel, b, arranged to revolve in a trough containing the paste, as set forth, for the purposes specified.”

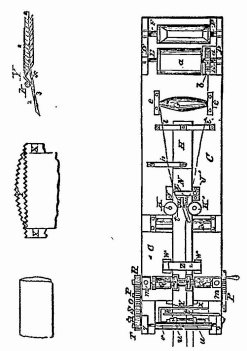

The invention set forth in the Pettee patent is illustrated in the foregoing engraving, and, in the specification, was described as an improvement on the machine of Armstrong, and consisted: (1) In the lateral adjustment of the plate to which the spindle, which carries the roll of paper, is journaled. (2) In the lateral adjustment of the plate which carries the pasting device. (3) In folding the continuous sheet of paper by sharp-edged pulleys, which crease the paper, and others that fold it down, dispensing with the “former.” (4) In making the pulleys adjustable laterally as to each other, and to the paper, to determine the creases for different sized bags. (5) In the rollers which guide the paper to the severing device. (6) In the construction and adjustability of the striker to and from its center of rotation, and in regard to the rollers. (7) In the pasting blade, which transfers the paste from the roller to the lap of the bag, the blade having a projection, which determines its action on the paste-roller in respect of the amount of paste transferred from the latter. (8) In the roller with angular projecting plates, acting in combination with the paste-roller, to determine the width of the paste on the latter.

The claims were as follows: “(1) Hanging the spindle, G, which carries the roll of paper to a plate, E, so secured to the frame as to be readily adjusted laterally thereon, for the purpose specified. (2) So connecting the plate, D, which carries the roller, I, and the pasting device to the frame, that the whole may be adjusted laterally on the said 655frame for the purpose specified. (3) Folding the continuous sheet by means of a pulley or pulleys, M, M, or their equivalents, in combination with the horizontal pulleys, d, d, or their equivalents, to the same, the sharp edges of the pulleys forming the crease at the proper place in the paper, and the pulleys, d, d, or their equivalents, turning down the fold determined by the creasing pulleys, thereby dispensing with the objectionable ‘former’ used in the machines for making paper-bags. (4) So securing the creasing pulleys, M, M, to the shaft, L, that they can be adjusted thereon, in respect to each other and to the paper, for the purpose described. (5) The roller, h, h, secured to the bar, P, and so arranged as to prevent a lateral sagging of the paper without disturbing the creases made by the pulleys, M, M. (6) So constructing the revolving striker that the striking bar can be moved to and from the center of rotation and secured after adjustment, for the purpose specified. (7) The revolving striker, when arranged in respect to the rollers, v, v, and the rollers, w and w“, as and for the purpose herein set forth. (8) Imparting to the pasting blade, 15, by the devices herein described, or their equivalents, the motion described to and from the pasting roller, as well as the motion described to and from the folding rollers, for the purpose herein set forth. (9) The beveled portion of the plate, 15, so formed and arranged as to conform or nearly conform to the circumference of the roller, 6, and so as to effectually transfer the paste to and spread it over the fold at the bottom of the bag, as described. (10) The roller, 7, with its angular projecting plate, 22, when combined and operating in conjunction with the paste-roller, 6, substantially as and for the purpose herein set forth.”

George Harding, for complainants.

T. W. Clarke, for defendant

LOWELL, District Judge. A preliminary Injunction, in patent eases, ought not to be granted where there are new and difficult questions to be decided, or where there is anything in the position or relations of the parties which would cause it to operate unjustly. The defendant insists that there are considerations of the latter kind arising out of the plaintiffs' delay to prosecute. He says the infringement was known to them before January, 1871, and this bill was filed in September. If it were true that there had been any license, express on implied, or if the defendant had been misled by the conduct of the plaintiffs, or if there had been even such hesitation as to show a doubt of their own title on the part of the patentees, a court of equity might refuse its summary interposition. But in this case, the plaintiffs' title to the two patents relied on in this motion is of long continuance, and was well known to the defendant. The misleading, if any, was on the other side, for the defendant wrote to the plaintiffs' solicitor, in March, 1871, that his machines were new and valuable; that they did not infringe on any patent, but were themselves in the course of being patented, and that he should be willing to sell them to the plaintiffs for a certain price. This negotiation was never completed, and on the 18th of July, the plaintiffs' agent went to the defendant's factory and saw one of his machines. There is no evidence that before that day its character was known to the plaintiffs. A delay of three months in filing the bill, the defendant not having been induced to change his position, or, so far as appears, having had any communication with the plaintiffs in the interval, is no ground for refusing the injunction.

Upon this hearing, the title of the plaintiffs has been admitted, and the validity of the Armstrong and Pettee patents has not been denied. The only points presented by the affidavits relate to the alleged infringement of the first, second, third, and sixth claims of the Armstrong patent, and of the first, eighth, and ninth claims of the Pettee patent. To sustain the issue on their part, the plaintiffs introduced a model, which Mr. Howlett, president of the plaintiff company, who saw the defendant's machine at work in July, as above mentioned, swears to as a true representation of it, and some bags, which he says he procured when he was there. It is not denied that if the machine is like the model, it infringes several of the claims; but the defendant himself, his foreman, and Mr. Edson, an expert, made affidavit to certain differences between the two. The plaintiffs, in reply, introduced a patent issued to the defendant since the affidavits in chief were filed, with evidence tending to show that it is for the same machine which he is using; and this patent certainly does describe a machine resembling the model in the disputed particulars. The defendant objects to the introduction of these papers at this time, as not being in reply to his case. This objection is sound. There would be great danger of surprise if the plaintiffs could strengthen their own case on the question of infringement under the guise of a reply. The evidence was not accessible when the plaintiffs' case was made up but that is no reason for permitting it to be brought in irregularly, though it might have been cause for varying the order of proof on suitable terms, giving the defendant an opportunity to answer the new matter. It is admissible in reply to the defendant's own affidavit, as tending to contradict his description of the machine by showing that he has made a different statement to the patent office. Admitted for that purpose, it has a tendency to neutralize Mr. Binney's evidence, and even to throw some doubt on the good faith if his defense, which in other respects is not satisfactory. He does not produce his machine, nor any model or drawing of it; does not rely on his own patent; 656does not bring forward the bags with which be supplies the trade; but contents himself with attacking the plaintiffs' model, denying that it can be a true copy of his machine, with pointing out certain discrepancies in it, and with showing certain bags that were made experimentally at his factory, and show marks of the differences between the two machines. There is some evidence, too, that his factory was not to be visited by strangers. The plaintiff must succeed, no doubt, by the strength of his own evidence; but in weighing it and passing upon its truth and correctness, the mode in which it is met by the defendant is a proper matter for consideration, and I must say that the defendant's course in this case does not lead me to construe the doubtful points favorably to him.

The two main points of difference relied on, are the parts of the machine coming under the first claim of Armstrong and of the eighth of Pettee. The first is for upper and lower knives, with their serrated edges, so arranged, in combination with the revolving striker or its equivalent, that the paper is forced by the striker against these edges, and cut in a particular shape. The defendant has the arrangement of knives and a striker, which reciprocates instead of revolving, and he says that it does not wholly sever the paper, but only brings it just far enough against the edges of the knives to cause perforations in the paper, which is then torn apart in the line of the perforations by the tension of the next pair of rollers. This statement, I doubt. It is opposed to the direct evidence of the plaintiffs' witness, and to the appearance of the bags produced by him, and is highly improbable. But, granting it to be true, it amounts only to this—that the defendant's striker is so imperfectly organized in the combination as to make a further process necessary. The striker performs the same office, as far as it goes, and in the same way; it brings the paper against the edges of the knives, and establishes a line of cutting, though it does not complete the operation. It is an imperfect infringement, because the machine is imperfect; but it is still an infringement. So of the eighth claim of Pettee. Before his time, bags came out of the machine unfinished at the bottom. His improvement, in this respect, consists in carrying the bag over a pair of horizontal rollers, and just as the lower end of the bag passes over the space between these rollers, it is struck by a plate or knife, which creases it, and forces the crease between the rollers. This plate or knife moves to and from a roller covered with paste, and deposits paste in the crease which it makes, so that, when the rollers have pressed it, the bottom is complete. This eighth claim is: “Imparting to the pasting blade, 15, by the devices herein described, or their equivalents, the motion described to and from the pasting roller, as well as to and from the folding rollers, for the purpose herein set forth.” The defendant has a blade or knife, or plate, which moves to and from a pasting roller, and to and from a pair of horizontal folding rollers, by which he creases and pastes the bottom of the bag. He says that this plate strikes the bag just before, instead of at the moment it reaches the intersection of the rollers, and spatters the paste upon it, instead of wiping itself on it; but I cannot see that this affects the mode of operation, excepting that it may do the work less well. The defendant's expert says that Pettee, in his eighth claim, describes his invention as imparting to the pasting blade a described motion by described means or their equivalents, and he then points out differences in the motion and in the means. He does not say whether these differences are formal or not; whether the defendant's means are well-known substitutes for those of the plaintiffs. He evidently does not consider the moving of the pasting blade to and from the pasting roller, so as to meet the end of the bag at the proper time, to crease and paste it, as of the essence of the claim; but the precise form of motion, and the precise means of imparting it, are what he regards. Considering what Pettee, upon the evidence, might be expected to mean, and what he fairly may mean, this is too narrow a view of that claim, and his idea cannot he borrowed by making some slight alteration of the details of the motion, especially when the variation is not shown to have required invention.

It is noticeable that in neither of these parts of the machine, as represented in the affidavits, is there any pretense of an improvement on Armstrong and Pattee, nor of any reversion to an earlier type of paper-bag machines, but a device admitted to resemble his very much in construction, but said to be incapable of readily doing the work at all times; for, in respect to both of them, they say there is great danger of injuring the bags unless everything goes at its best. This singular state of things gives some weight to the plaintiffs' theory that the machine was partly disorganized when these experiments were made upon it; that the striker and paster did not show their fan and usual operations, but were crippled for the time being. Besides these claims, there are two others of great importance, concerning which there seems to be scarcely a doubt raised by the testimony. Armstrong's second claim is for rollers which bold the bag during the operation of the striker. The defendant says his rollers operate to tear the paper by tension; but this only shows that they have a double use. It cannot be denied that they likewise hold the paper while it is subjected to the operation of the striker, which is the claim of the patent. Then there is Armstrong's third claim for rollers, in combination with the blade over which the paper is formed. The combination consists in cutting a piece out of the blade and enlarging the corresponding 657part of the upper roller by collars, so that the rollers meet upon the paper and carry it forward without interfering with the blade. In the defendant's machines the blade is cut away on each side, instead of in the middle, and there are corresponding enlargements on the under roller, instead of the upper one, so that the same effect is produced, and in the same way. The defendant's expert says: “I do not find in the Binney machine any collars on either the upper or lower roll, nor any openings in the blade, but I do find that the former (blade) is made with a neck fitting in between two rolls and having a play vertically, which vertical play is impossible in the Armstrong machine, and serves an important purpose in the cutting-off process of Binney.” The vertical play has nothing to do with the combination of Armstrong's third claim, and a neck fitted in between two rolls is plainly the same as a cap fitted between two rolls: and the expert does not venture to say that there is any mechanical difference. How he can even say that the enlarged parts of the lower roll are not collars, I do not quite understand, though perhaps there is something in the mode of making them which permits the use of a different name. The thing is the same, with scarcely a colorable difference. I find that at least four of the most important claims of the two patents are infringed—two of the four without any question—and this is enough for the purposes of this motion.

No reason being shown for doubting the validity of these two patents, and nothing in the acts or situation of the parties to render the injunction unjust in its application, I must order it to issue.

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.