259

Case No. 14,213.

TUCK v. BRAMHILL.

[6 Blatchf. 95; 3 Fish. Pat Cas. 400; Merw. Pat. Inv. 428.]1

Circuit Court, S. D. New York.

April 14, 1868.

PATENTS—SEPARATE CLAIMS IN ONE—DISCLAIMER—EFFECT OF—COSTS.

1. In the letters patent, granted June 26th, 1855, to Joseph Tuck, for “improvements in packing for stuffing boxes, &c,” the claim, in these words: “The forming of packing for pistons or stuffing boxes of steam engines, and for like purposes, out of saturated canvas, so cut as that the thread or warp shall run in a diagonal direction from the line or centre of the roll of packing, and rolled into form, either in connection with the india-rubber core, or other elastic material, or without, as herein set forth,” is a claim for a new article of manufacture, and not for any special use thereof.

2. The claim to the forming of the roll, “either in connection with the india-rubber core, or other elastic material, or without,” is equivalent to two separate claims, one for the forming of the roll with the core, and one for the forming of it without the core.

3. The roll without the core being old, but the roll with the core being new, the patentee had a right, under the 7th section of the act of March 3, 1837 (5 Stat. 193), to enter a disclaimer, disclaiming the forming of the roll without the core; and limiting his claim to the forming of the roll with the core.

[Cited in Session v. Romadka, 145 U. S. 40, 12 Sup. Ct. 801.]

4. Although such disclaimer is entered after the commencement of a suit on the patent by the patentee, he can, nevertheless, under the 7th and 9th sections of the said act of 1837, recover in such suit unless he unreasonably neglected or delayed to enter such disclaimer, but he cannot recover costs therein.

[Cited in Taylor v. Arcner, Case No. 13,778; Smith v. Nichols, 21 Wall. (88 U. S.) 117; Burdett v. Estey, Case No. 2,145; Electrical Accumulator Co. v. Julien Electric Co., 38 Fed. 135; Guaranty Trust & Safe-Deposit Co. v. New Haven Gaslight Co., 39 Fed. 269; Sessions v. Romadka, 145 U. S. 41, 12 Sup. Ct. 802.]

[This was a bill in equity filed to restrain the defendant, William Bramhill, from infringing letters patent No. 13,145, for “improvements in packing for stuffing boxes,” etc., granted to plaintiff, Joseph H. Tuck, June 25, 1855. The nature of the invention, the claim of the patent, and the facts-of the case are fully set forth in the opinion of the court]2

260

George Gifford, for plaintiff.

Charles M. Keller, for defendant.

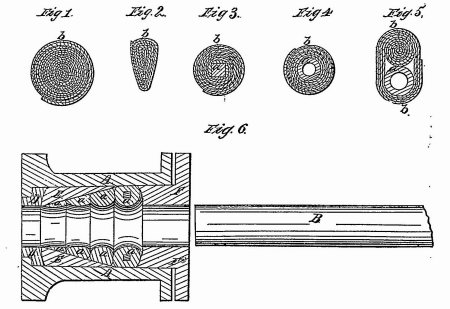

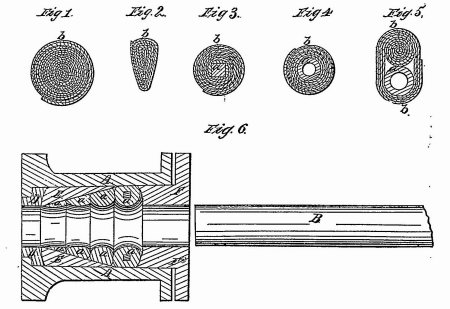

BLATCHFORD, District Judge. The patentee says, in his specification: “My invention relates to an improved manner or mode of making or forming packing for pistons, valves, and other parts of steam engines, and for like purposes, from india-rubber and canvas saturated with india-rubber, or other suitable material or composition.” He describes, as follows, the mode of carrying out his invention in practice: “I first take canvas, or other suitable material, and saturate it with a solution of india-rubber, or other equivalent composition. I then cut the canvas, thus prepared, in a diagonal manner, into strips of any required width, cement the diagonal ends together, so as to form any length of fillet required, then roll it up into a roll, and allow it to cement in a firm but elastic or flexible roll, of any suitable diameter required. In cases where greater elasticity is required, I roll the canvas round a core or centre-piece of india-rubber, or other suitable elastic material.” Annexed to the patent are six figures of drawings, which are described in the specification. Figure 1 represents a section of the packing, which is rolled up from its own centre, and may be round, or nearly so. Figure 2 represents a section of the packing, which is rolled loosely at one point, and tightly at the opposite point, whereby a conical form may be given to the packing, so as to be used in conical seats. Figure 3 represents a section of the packing, rolled around an elastic core of rubber, which core may be square, round, oblong, oval, or of any desired form which the roll of packing is designed to possess. Figure 4 represents a section of the packing, having a hollow cylindrical core. Figure 5 represents a section of the packing made according to the combined forms shown in figures 1 and 4, the canvas being first rolled from its own centre, and then rolled around the core, so as to embrace both its own coils and the core in its outer folds. The specification then says: “In all these figures, but a modification of one general plan is illustrated, namely, the rolling of canvas, first saturated as described, into a fillet, in any reasonable length, and of any diameter, from which packing may be cut in lengths, as required. A packing, such as herein described, has heretofore not been known as an article of commerce or of manufacture, and, as such, I claim to be the first inventor or producer of it.” Figure 6 represents a vertical section through a packing-box, showing the manner of applying the packing to the cylinder of a steam engine. The specification adds: “Any of the forms of packing represented in the several figures 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5, may be used, that represented at figure 2 being more particularly adapted to the lower part of the packing-box, on account of the conical form of the block

[Drawings of patent No. 13, [45, granted June 26, 1855, to J. H. Tuck; published from the records of the United States patent office.]

261 behind it. Piston heads and valves, or other places, may be packed in a similar manner, the packing being cut off in suitable lengths, to suit the thing to be packed. By this mode of manufacture, it will be seen that each fold of the packing in contact with the rubbing or moving surface must be entirely worn away, and cannot be drawn out by the rubbing surface, (as is frequently the case when packing is made in concentric folds of prepared canvas,) being held in its place-by the ring above and below it.” The claim is as follows: “The forming of packing for pistons or stuffing boxes of steam engines, and for like purposes, out of saturated canvas, so cut as that the thread or warp shall run in a diagonal direction from the line or centre of the roll of packing, and rolled into form, either in connection with the india-rubber core, or other elastic material, or without, as herein set forth.”

261 behind it. Piston heads and valves, or other places, may be packed in a similar manner, the packing being cut off in suitable lengths, to suit the thing to be packed. By this mode of manufacture, it will be seen that each fold of the packing in contact with the rubbing or moving surface must be entirely worn away, and cannot be drawn out by the rubbing surface, (as is frequently the case when packing is made in concentric folds of prepared canvas,) being held in its place-by the ring above and below it.” The claim is as follows: “The forming of packing for pistons or stuffing boxes of steam engines, and for like purposes, out of saturated canvas, so cut as that the thread or warp shall run in a diagonal direction from the line or centre of the roll of packing, and rolled into form, either in connection with the india-rubber core, or other elastic material, or without, as herein set forth.”

The principal defence set up in the answer, is want of novelty in the invention. The answer avers, that, before the alleged invention by the plaintiff, strips of canvas and other cloth, saturated or coated with india-rubber, were rolled up into rolls, both upon and without an inner core of india-rubber, and with the threads of the cloth placed in a direction diagonal to the axis of the roll, and in various other directions, constituting a new manufacture for various uses, and that the application of such manufacture to any special purpose, such as the packing of stuffing boxes, is not an invention, and does not constitute the subject-matter of letters patent. The answer also avers, that the defendant has never made, used, or sold, what is claimed as the invention of the plaintiff, in the patent.

The evidence as to infringement shows the sale by the defendant of two different rolls of packing, which are produced, one of larger diameter than the other, and each having an elastic solid india-rubber core, the section of which core is a square, the rolls of packing being cylindrical. It is also shown, that the defendant, on inquiry being made for “Tuck's patent packing,” sold packing similar to the two rolls referred to. The two rolls were purchased by a person who sells the packing as an agent or licensee of the plaintiff, and for the purpose of their being used as evidence of their sale by the defendant The two rolls are made exactly in accordance with the packing described in the patent.

The defendant showed, by satisfactory proof, that an article, made in the same manner as the plaintiff's packing, but without a core, was known and used several years before the invention of the plaintiff was made. No evidence was given of any prior knowledge of any such article made with a core.

After the testimony on both sides had been put in before the examiner, the plaintiff, on the 18th of February, 1867, filed in the patent office a disclaimer, setting forth that he was still the sole owner of the patent, and entering his disclaimer “to that part of the claim which covers the packing therein described without a core, thereby causing the claim to include only the packing formed out of saturated canvas, so cut as that the thread or warp shall run in a diagonal direction from the line or centre of the roll of packing, and rolled into form in connection with and around an india-rubber core, or one of other elastic material, meaning the said claim to include only the combination of an elastic core, with saturated canvas, having threads running in a diagonal direction, as described in said patent, wound around the same.”

The plaintiff claims that he is entitled to a decree for a perpetual injunction restraining the defendant from making, using, or selling, the packing which has a core, and for an account in regard to the packing of that kind which he has made and sold. The claim of the patent is, undoubtedly, as the defendant contends, and as the plaintiff does not deny, for an alleged new article of manufacture, and not for any special use thereof. But the defendant insists, that what is claimed in the patent is not so divisible as to admit of a disclaimer being made to a part of it and that the alleged invention is not so divisible; in other words, that the plaintiff did not make, and the patent does not make, claim to two separable inventions, but to only one invention, and that that invention is shown not to have been new with the patentee. The ground taken by the” defendant is, that the patentee, in his specification, states his invention to be merely the roll formed in the manner described, and that the modification of making it with a core, so as to produce greater elasticity, was not a separate invention in fact and is not spoken of in the specification as a separate invention, distinct, as such, from the making; of the roll without a core. It is true, that the specification speaks of the plan of rolling the canvas, first cut and saturated as described, into a fillet of any reasonable length and of any diameter, as one general plan, and says that the five figures of sections of rolls show what are only modifications of such one general plan. But the claim claims the forming of the roll “either in connection with the india-rubber core, or other elastic material, or without.” This is equivalent to two separate claims—one for the forming of the roll with the core, and one for the forming of it without the core. The patentee might have made two such claims, separately numbered, and both would have been good claims, if the inventions were new with him. He did that, in effect, in the claim he made. The roll with the core is a distinct thing from the roll without the core. It has a utility of its own, as is quite apparent from the fact that the defendant sells it. The prior existence of the roll without 262the core is shown, hut it is not shown that the roll with the core was known or used before the invention of it by the plaintiff. If the plaintiff had known of the existence of such roll without the core, he could have patented the combination of it with a core, if such combination was invented by him and was new. There is sufficient utility and invention in such combination to support a patent The result produced by the combination is a new article, and, being useful, it is patentable. Crane v. Price, Webst Pat Cas. 409; McCormick v. Seymour [Case No. 8,726].

It having been shown that the forming of the roll in the manner described, without the core, was old, the next question is, whether the plaintiff could disclaim, as he has attempted to do, the forming of the roll without the core and limit his claim to the forming of the roll with the core. The 7th section of the act of March 3, 1837 (5 Stat 193), provides for the making of a disclaimer, where a claim is too broad, and claims more than that of which the patentee was the original or first inventor; but the disclaimer cannot be made unless some material and substantial part of the thing patented is truly and justly the invention of the patentee, and, in such case, he is authorized to make disclaimer of such parts of the thing patented as he does not claim to hold by virtue of the patent. The defendant contends, that the claim of this patent is not equivalent to two claims, and that, therefore, under the statute, the patentee has no right to disclaim any thing in the claim. But this objection has been already disposed of. The forming of the roll without the core is one material and substantial part of the thing patented. The forming of the roll with the core is another material and substantial part of the thing patented. The patentee was not the first inventor of the former. He was the first inventor of the latter. The two are clearly separable and distinguishable. The claim is too broad, and claims more than that of which the patentee was the first inventor. A clear ease, therefore, existed, under the 7th section of the act of March 3, 1837, for a disclaimer by the patentee of so much of his claim as covers the forming of the roll without the core. The disclaimer goes exactly to that extent. It disclaims that part of the claim “which covers the packing therein described without a core;” and then it goes on to state what the claim will De after such disclaimer, namely, that it will “include only the packing formed out of saturated canvas, so cut as that the thread or warp will run in a diagonal direction from the line or centre of the roll or packing, and rolled into form in connection with and around an india-rubber core, or one composed of other elastic material,” and that it will “include only the combination of an elastic core with saturated canvas having threads running in a diagonal direction, as described in the said patent, wound around the same.” This disclaimer is unambiguous, and leaves the claim as if it had originally claimed only such combination. It is substantially just such a disclaimer as the supreme court, in Silsby v. Foote, 14 How. [55 U. S.] 218, 221, held to be valid. The claim there was, to “the application of the expansive and contracting power of a metallic rod, by different degrees of heat, to open and close a damper, which governs the admission of air into a stove, or other structure, in which it may be used, by which a more perfect control over the heat is obtained than can be by a damper in the flue.” It having been shown that the application of the expansive and contracting power of a metallic rod, by different degrees of heat to regulate the heat of other structures than a stove in which the rod was acted upon directly by the heat of the stove, or the fire which it contained, was not new with the patentee, he entered a disclaimer “to so much of said claim as extends the application of the expansive and contracting power of a metallic rod, by different degrees of heat, to any other use or purpose than that of regulating the heat of a stove in which such rod shall be acted upon directly by the heat of the stove, or the fire which it contains.” The supreme court sustained such disclaimer as a good disclaimer, under the 7th section of the act of 1837.

But the defendant contends, that the disclaimer in this case, if properly made at all, cannot affect the issues in this suit because it was not filed till after the commencement of the suit. In other words, the defendant contends that the plaintiff cannot recover in this suit, because the claim, as it stood when the suit was brought embraced more than that of which the plaintiff was the first inventor. In urging this view, the defendant relies on the general principle of law to that effect as recognized before the act of March 3, 1837, was passed, and on the provision of the 7th section of that act, that “no such disclaimer shall affect any action pending at the time of its being filed, except so far as may relate to the question of unreasonable neglect or delay in filing the same;” and he insists, that the claim of the patent must be construed, for the purposes of this suit, as if no disclaimer had been filed. But the 7th section of the act of 1837 must be construed in connection with the 9th section of the same act. The latter section provides, “that whenever, by mistake, accident, or inadvertence, and without any willful default or intent to defraud or mislead the public, any patentee shall have, in his specification, claimed to be the original and first inventor or discoverer of any material or substantial part of the thing patented, of which he was not the first and original inventor, and shall have no legal and just right to claim the same, in every such case the patent shall be deemed good and valid for so much of the invention or discovery 263as shall he truly and bona fide his own, provided it shall be a material and substantial part of the thing patented, and be definitely distinguishable from the other parts so claimed without right, as aforesaid; and every such patentee, his executors, administrators, and assigns, whether of the whole or of a sectional interest therein, shall be entitled to maintain a suit, in law or in equity, on such patent, for any infringement of such part of the invention or discovery as shall be bona fide his own, as aforesaid, notwithstanding the specification may embrace more than he shall have any legal right to claim.” Under this provision of the 9th section, taken by itself, the plaintiff is entitled to recover in this case, without having entered any disclaimer. The patentee, by inadvertence and mistake, and without any willful default or intent to defraud or mislead the public, claimed, in his claim, to be the original and first inventor of forming the roll without the core, which was a material and substantial part of the thing patented; but still, under this provision of the 9th section, the patent is valid for the forming of the roll with the core, which was first invented by the plaintiff, and is a material and substantial part of the thing patented, and is definitely distinguishable from the forming of the roll without the core. Therefore, the plaintiff, even without the disclaimer, is authorized, by the 9th section, to maintain this suit, for the infringement of so much of the claim as covers the forming of the roll with the core, although the claim embraces also the forming of the roll without the core. It is provided, indeed, by the 9th section, that “no person bringing any such suit shall be entitled to the benefit of the provisions contained in this section, who shall have unreasonably neglected or delayed to enter at the patent office a disclaimer, as aforesaid.” It is not pretended, however, that the patentee in this case has been guilty of any such neglect or delay. It is further provided, by the 9th section, that, where the plaintiff recovers under that section, “he shall not be entitled to recover costs against the defendant, unless he shall have entered at the patent office, prior to the commencement of the suit, a disclaimer of all that part of the thing patented which was so claimed without right” Therefore, the plaintiff, can recover no costs in this case.

But, it is urged that the provision of section 7, that “no such disclaimer shall affect any action pending at the time of its being filed, except so far as may relate to the question of unreasonable neglect or delay in filing the same,” forbids a recovery by the plaintiff in this suit notwithstanding the provisions of the 9th section. This is not so. It is true, that Judge Story, in Reed v. Cutter [Case No. 11,645], says, that if a disclaimer is filed during the pendency of a suit the plaintiff will not be entitled to the benefit thereof in that suit; and that the same judge, in Wyeth v. Stone [Id. 18,107], says, that the disclaimer mentioned in the 7th section, must be interpreted to apply solely to suits pending when the disclaimer is filed in the patent office, and the disclaimer mentioned in the 9th section to apply solely to suits brought after the disclaimer is so filed, and that the proviso to the 7th section, as to the disclaimer affecting a pending suit, prevents its affecting in any manner whatsoever a suit pending at the time it is filed. But the plaintiff does not need to claim any benefit in this suit from the disclaimer. He recovers in this suit by virtue of the 9th section, it not appearing that he unreasonably neglected or delayed to enter a disclaimer. I cannot concur, however, in Judge Story's view of the provision in the 7th section, as to the disclaimer's affecting a pending suit. I understand that provision to mean, that a suit pending when the disclaimer is filed, is not to be affected by such filing, so as to prevent the plaintiff from recovering in it unless it appears that the plaintiff unreasonably neglected or delayed to file the disclaimer. The “unreasonable neglect or delay,” mentioned in the 7th section, manifestly refers to the unreasonable neglect or delay mentioned in the 9th section, and the disclaimer mentioned in the 9th section is clearly the disclaimer provided for in the 7th section. Moreover, the provision of the 9th section, that the plaintiff, where he is entitled to recover under that section, shall not recover costs, unless he has entered a disclaimer, prior to the commencement of the suit of what he claimed without right, is a strong implication, that where he does not enter the disclaimer until after the commencement of the suit he may still recover in the suit, if otherwise entitled to do so, but without recovering costs. And such has been the view heretofore held by Mr. Justice Nelson, in this court In Guyon v. Serrell [Case No. 5,881], he allowed a recovery, without costs, in a case where a disclaimer was filed after suit brought; and in Hall v. Wiles [Id. 5,954], he says: “If the disclaimer was entered in the patent office before the suit was instituted, the plaintiff recovers costs in the usual way, independently of any question of disclaimer. But if, in the progress of the trial, it turns out that a disclaimer ought to have been made as to part of what is claimed, the plaintiff may recover, but will not be entitled to costs.” Of course it follows, that if a disclaimer is made after suit brought, the plaintiff, may still recover, but without costs.

The plaintiff is entitled to a decree for a perpetual injunction, as prayed for in the bill, in respect to the packing formed with a core, and for an account in respect to such packing, and for a reference to a master to take and state such account He will not be entitled to recover any costs in the suit.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.

261 behind it. Piston heads and valves, or other places, may be packed in a similar manner, the packing being cut off in suitable lengths, to suit the thing to be packed. By this mode of manufacture, it will be seen that each fold of the packing in contact with the rubbing or moving surface must be entirely worn away, and cannot be drawn out by the rubbing surface, (as is frequently the case when packing is made in concentric folds of prepared canvas,) being held in its place-by the ring above and below it.” The claim is as follows: “The forming of packing for pistons or stuffing boxes of steam engines, and for like purposes, out of saturated canvas, so cut as that the thread or warp shall run in a diagonal direction from the line or centre of the roll of packing, and rolled into form, either in connection with the india-rubber core, or other elastic material, or without, as herein set forth.”

261 behind it. Piston heads and valves, or other places, may be packed in a similar manner, the packing being cut off in suitable lengths, to suit the thing to be packed. By this mode of manufacture, it will be seen that each fold of the packing in contact with the rubbing or moving surface must be entirely worn away, and cannot be drawn out by the rubbing surface, (as is frequently the case when packing is made in concentric folds of prepared canvas,) being held in its place-by the ring above and below it.” The claim is as follows: “The forming of packing for pistons or stuffing boxes of steam engines, and for like purposes, out of saturated canvas, so cut as that the thread or warp shall run in a diagonal direction from the line or centre of the roll of packing, and rolled into form, either in connection with the india-rubber core, or other elastic material, or without, as herein set forth.”