Case No. 14,110.

24FED.CAS.—6

TOWLE v. The GREAT EASTERN.1

District Court, S. D. New York.

Nov. 12, 1864.

SALVAGE—BY PASSENGER—NATURE OF SERVICE—UNSUCCESSFUL EXPERIMENTS.

[The services of a passenger, who, after the officers of the ship in two days of effort have exhausted all their means to get control of the rudder, devises, and, with the aid of men put under his direction by the captain, executes, a plan for that purpose, thereby rescuing the ship from peril, are of such an extraordinary character, and beyond the line of his duty to assist in working the ship by usual and well-known means, as to entitle him to salvage, although he may have obtained his idea from a previous unsuccessful experiment of the engineer.]

[Cited in The Alaska, 23 Fed. 604.]

[This was a libel in rem by Hamilton E. Towle against the Great Eastern for salvage.]

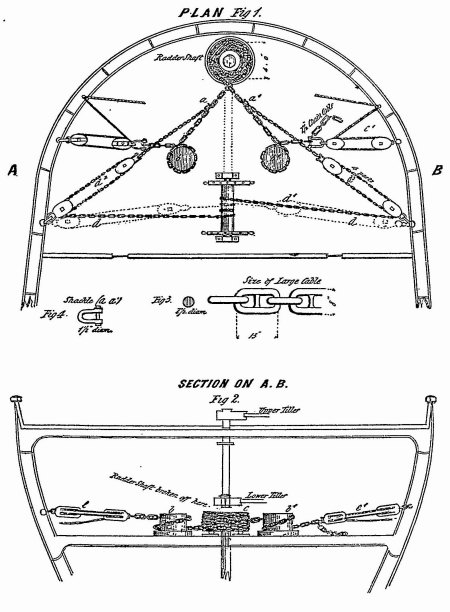

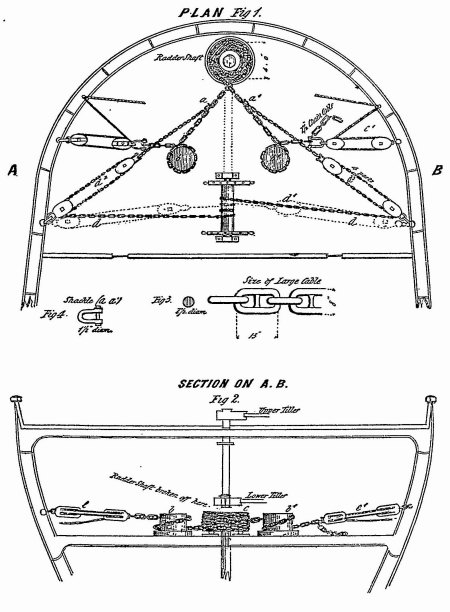

The following diagrams were used on the trial, for the purpose of explaining the nature of the injury to the ship, and the character of the services performed by the libellant:

76[Temporary steering gear used on board the Great Eastern after the breaking of the rudder shaft in the gale of september 12, 1861. By Hamilton E. Towle C. E., Boston U. S.]

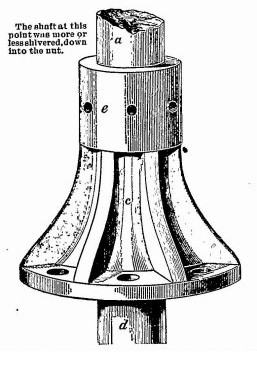

(a) The rudder shaft just below the point of fracture.

(e) The nut which was at one time attempted to be unscrewed.

(c) The ribbed frustum of cone.

(d) The rudder shaft below the base of the cone, and passing down through the middle, or steerage deck, terminating in the rudder blade.

Figure 1 is a plan of the middle deck of the Great Eastern, showing the arrangement of the temporary steering gear employed to operate the rudder after the accident. This sketch also shows by the dotted lines the lower tiller and its running gear before the accident. Figure 2 is a vertical cross section through the stern of the ship, showing where the rudder-shaft, ten inches in diameter, broke off, and the bitts (bb), which were made use of to receive the sudden strains transmitted through the cable from the rudder; also the end tackles (ee1), employed to keep the cable tight around the bitts, when the rudder was in proper position for steering any course. Figure 1 (d2 and d3) shows the running gear after having been disconnected from the lower tiller and attached to the cable by shackles at (aa1). The rudder shaft broke two feet six inches above the middle deck, at the upper side of and partially in a nut fifteen inches in diameter, twelve inches high; which nut was screwed upon the rudder-shaft above a cast-iron bell-shaped disk, having a diameter of two feet nine inches, between the base of which and the deck were interposed iron balls six inches in diameter, to reduce the friction in moving the rudder. This disk being constructed with webs to support the broad part, greatly facilitated fastening the cable upon it so as not to slip; small chains, ⅜, ⅝, ¾ inch, were used to lash the different turns of the cable to one another and to the conical disk. A single link of the large cable weighs about sixty pounds, and fifteen fathoms (ninety feet) in length of it was employed. The steering wheel was employed as usual, the end tackles (ee1) making corresponding motions. This apparatus was used for forty-eight hours continual steaming at nine knots per hour, when the big ship arrived at Queenstown harbor.

Curtis & Hall, for libellant.

Evarts, Southmayd & Choate, for claimants.

SHIPMAN, District Judge. On the 10th of September, 1861, the steamship Great Eastern left Liverpool for New York, with about four hundred passengers and a considerable cargo, together with about four hundred persons as officers and crew, including engineers, firemen, servants, &c. She was, as is well known, the largest ship that ever floated the sea, and was of great value. Her original cost was very large, but owing to her great draught of water and unwieldy proportions, which limited in many directions her general usefulness as an instrument of commercial enterprise, it is difficult to state her exact value at the time the events occurred upon which this suit is founded. But, from the evidence before this court, it is safe to conclude that she was at that time worth more than half a million of dollars. Beyond this, her value is not important for the purposes of this case. Among her passengers on this voyage was the libellant in this suit On Thursday, the 12th of September, two days after the ship left Liverpool, and about two hundred and eighty miles west of Cape Clear, she encountered a heavy storm, which did great damage to, and finally swept away her paddle wheels and several of her boats. Her screw or propeller, however, remained substantially uninjured, and by this she could make very good headway when under steam. During the evening or night of the 12th, she fell off into the trough of the sea, and rolled with such violence as to carry from side to side of the ship all the movable objects on her deck and in her cabins. Much of her furniture was broken up and destroyed, several of her crew and passengers injured, and a great part of the luggage of the latter was drenched and crushed into a mass of worthless rubbish. The immense size of the ship rendered her motions, when rolling in the trough of a heavy sea, much more dangerous and destructive than those of a ship of ordinary dimensions. During the night it was discovered that her rudder shaft, which was large and of wrought iron, had been twisted off below all the points of connection with the steering gear. The ship, 78therefore, lay helpless in the trough of the sea, rolling heavily with every swell. Her sails were blown away in a subsequent attempt to control her movements by them, and no means were left by which her head could be brought up, and her position on the sea changed. She was as unmanageable as if her rudder had been entirely gone. The only way, therefore, to get any control of the motions of the ship was to secure some kind of efficient steering-gear by attaching it to the rudder shaft below the point of fracture and connecting it with the wheel. This was a work of considerable danger and of great difficulty. It was, however, finally done, and the ship was again got under control, taken out of the trough of the sea, and steered safely back to port. The libellant claims that he devised and executed the plan of this new steering-gear, and the means by which it was made available, and that the ship was thus saved from great peril chiefly through its instrumentality. To recover compensation, in the nature of salvage, for this service, he has brought this suit

Before passing upon the questions of law which have been raised and discussed on this trial, I will state the facts which I hold to be proved by the evidence. In doing this I shall not detail the evidence further than may be necessary to enable me to state my own conclusions:

1. The ship was brought into a condition of great peril by the breaking of her rudder shaft in the afternoon, or during the night, of the 12th. In consequence of this accident she fell off into the trough of the sea and there lay in a helpless condition. The storm was very violent during Thursday night, but began to abate on Friday morning, and had, in the main, ceased on Saturday evening. But the ground swell continued and kept the ship rolling more or less until about 5 o'clock on Sunday evening, when her head was brought up and she was started on her course. During all this time she lay drifting upon the waves; every attempt to get control of her rudder, or rig other steering apparatus, having failed. It requires no argument and little evidence beyond what the common history of the sea furnishes, to prove that this immense and unwieldy ship, on the ocean, nearly three hundred miles from land, with eight hundred souls on board, in this disabled and helpless condition, was in great danger and exposed to numerous perils.

2. Between Friday morning and Saturday afternoon the officers of the ship had made repeated attempts to get control of her motions. It is not necessary to detail these experiments. It is sufficient to say that they all proved fruitless. Finally the chief engineer commenced unscrewing a large nut on the rudder shaft. This nut was on that part of the shaft which was below the upper deck, and in an apartment on the deck below at the stern of the ship. This apartment has been termed, in this case, the steerage deck. The rudder shaft passed up through it. On the shaft within this steerage deck was the frustum of a ribbed iron cone, through the centre of which the shaft passed. The base of this cone rested on iron balls, the balls running in a circular groove sunk in an iron plate fastened to the deck, which constituted the floor of the apartment. The cone was fastened to the shaft firmly by appropriate means, so that they revolved together as if one piece of iron. On the rudder shaft, at the top of the cone, was a large nut, the one already referred to, which was screwed down firmly on the head of the cone. This nut, it will thus be seen, kept the cone down to its proper position, so that the base was made to traverse on the balls, and the cone and nut formed together a head or collar which contributed to support the weight of the rudder and shaft. The rudder shaft bad broken off at or near the top of this nut. The last attempted experiment of the chief engineer was to unscrew this nut, with the design to secure, if possible, a tiller upon the end of the broken shaft, and thus, with the aid of the wheel in the steerage deck, to steer the ship. He had partly unscrewed the nut, though it was a work of considerable difficulty, as the nut and shaft turned by every blow of the sea on the rudder blade, when the libellant learned the fact The latter regarded the nut as a very important means of supporting the rudder and the shaft, and looked upon its removal with alarm, on the ground that if this support were removed, it might lead to a total loss of the rudder. He communicated his fears to the captain of the ship, and the engineer was ordered to desist. It is impossible to tell what would have been the result of this experiment had it been carried out, although by unscrewing the nut an inch the rudder fell half that distance; but it appears from the testimony of one of the witnesses that the engineer did not expect to be able to fit the tiller to the end of the broken shaft under three or four days. The captain seemed now to have lost confidence in the chief engineer's ability to restore the control of the rudder. His own efforts had failed. Attempts had been made to secure control by winding chains around the cone on the shaft, and connecting them with tackles fixed to the ship's sides, to be worked by men at each end. This failed. A spar was rigged over the stern of the ship as a temporary means of steering, and that also failed. Sails had been hoisted to change her position, but had been blown to pieces. It is evident, from the testimony, that after the captain had arrested the unscrewing of the nut, both he and his officers had exhausted their expedients for getting control of the rudder so as to steer the ship, and bring her up out of the trough of the swell. The situation of the ship and the persons on board of her was now such as might well alarm 79the most accomplished and intrepid navigator, and lead him to welcome any aid which gave any hope of relief, especially when it proposed no experiments which could involve the ship in new dangers.

3. The libellant is a civil and mechanical engineer, regularly educated for his profession, and, prior to taking passage in this ship, had had considerable experience in responsible stations, both at home and abroad, where high professional skill was required. He had not been an indifferent spectator of such of the various attempts as he had seen made to get the ship under control prior to the commencement of the unscrewing of the nut. He had revolved a plan in his own mind, drawn a sketch of it, had shown it to the chief engineer, who had treated it with rudeness, which is not surprising, when we remember that in every profession men are apt to be impatient of outside interference in times of perplexity and danger. The captain, however, “having exhausted his own expedients and those of his officers, and evidently alarmed for the safety of the ship, decided that the libellant should try his. He put a sufficient number of men at his disposal, and the libellant entered upon his work. He had already matured his plan, and, after ascertaining by calculations the necessary strength of the materials which he knew he could use, he felt confident that his plan was secure from danger or failure. He proceeded to the steerage deck with the men detailed to work under his directions. This was about 5 o'clock on Saturday afternoon. There is some conflict in the evidence as to who superintended the operation of screwing the nut back again; but on the whole evidence I think the weight of it sustains the statement of Mr. Towle that lie did. I will not here detail the progress of the libellant's labors. It is sufficient to state that after three hours labor, he succeeded in screwing the nut back to its place, and having obtained from the forward part of the ship an immense chain, weighing about sixty pounds to the link, which was let down into the steerage deck through a hole cut in the upper deck by his directions, he succeeded In winding around the cone on the rudder shaft a sufficient portion of this chain to constitute a cylinder or drum, and thus secured a leverage obtainable in no other way. The ends of the chain were then extended from the cylinder to two strong posts or bitts which came up through this deck. A turn was taken round each of these bitts, and the ends of the large chain were then connected with tackles fastened to the respective sides of the ship for taking up the slack and easing the strain on the wheel used immediately for steering. Smaller chains connected the wheel with the large chain before described, and the size of the shackles making the connections were arranged so that in the event of a break it would not occur in the great chain or its lashings, but in the smaller or connecting chains or shackles. The links of the large chain composing the cylinder were lashed to each other and to the base of the cone, by smaller chains which were passed through the holes in its base. The alternate links of the large chain on the inner coil, sank in between the ribs of the cone, and thus tended to prevent slipping and to diminish the strain on the lashings. The smaller chains connecting with the wheel were fastened to the large chain composing the cylinder and extending to and around the deck-bitts at a point between the bitts and the cylinder, so that in the event of the breaking of the smaller chains, the rudder would still be held in position by the large chain, as the latter was wound around the bitts by one turn, and the end secured to tackles fastened to the sides of the ship and manned for the purpose of taking up the slack and easing away, as the rudder shaft was turned one way or the other by the movement of the wheel. This is a brief and general outline of the plan devised and executed by this libellant for rescuing this ship from her perilous situation. It is difficult to make the description of the arrangement clear without drawings and illustrations addressed to the eye. This arrangement was completed during Saturday night and Sunday, and at 5 o'clock, p. m., on Sunday, the ship was brought up to the sea and put on her course.

4. The labor of the libellant, both manual and mental, during the execution of this plan, was very considerable—so much so as to reduce him at one time to a state of great exhaustion. It was attended with some danger, owing to the size of the chain, and the spanner with which the nut was screwed back. The large chain weighed sixty pounds to the link, and the spanner or wrench weighed one hundred and thirty pounds. The latter was suspended from the upper deck by ropes or chains, and used by holding it to the nut, securing it to the latter by a pin to prevent it from slipping, and then a blow of the sea on the rudder blade drove around the shaft, and brought the nut down on the thread. As the cone turned with the shaft, the constant swell of the sea kept both in motion, which increased the difficulty of lashing the links of the large chain, and made it a more or less dangerous work.

5. While the libellant was engaged in perfecting his plan for steering the ship, Captain Walker, who was in command of the Great Eastern, and his officers were also at work in connecting a large chain to the rudder, by passing it round the latter and securing it at the outer edge of the rudder-blade by a shackle, and then bringing one end over the larboard and the other over the starboard quarter of the ship, and securing them on deck. The object of this arrangement was also to aid in steering the ship, by manning the ends of the chain on deck, so that the rudder could be moved either way, as either end of the chain might be hauled on. How much this contrivance was used it is difficult to determine exactly from the evidence. I am satisfied, 80however, that it was greatly inferior and subordinate, both in its use and capacities, to that arranged by the libellant in the steerage deck. That the latter was the efficient and principal means by which this great ship, with her valuable cargo and priceless freight of human lives, was saved from a condition of peril, I cannot doubt, in view of the evidence. Well might Captain Walker exhibit a lively sense of gratitude toward the libellant, as the evidence discloses that he did, when the success of the latter's plan was demonstrated by trial.

In view of these facts and the well settled rules of law applicable to salvage claims, had the libellant fallen in with this ship thus at sea, disabled and at the mercy of the winds and waves, and had gone from his own vessel on board of her and rendered these services, I should feel no hesitation in pronouncing him a salvor, and entitled to a liberal reward. It is well said by Dr. Lushington, in the case of The Charlotte, 3 W. Rob. Adm. 71, that “According to the principles which are recognized in this court in questions of this description, all services rendered at sea to a vessel in danger or distress, are salvage services. It is not necessary, I conceive, that the distress should be actual or immediate, or that the danger should be imminent and absolute; it will be sufficient if, at the time the assistance is rendered, the ship has encountered any damage or misfortune, which might possibly expose her to destruction if the services were not rendered.” This doctrine has been repeatedly sanctioned by the courts of the United States, and very recently by this tribunal. See also Hennessey v. The Versailles [Case No. 6,365]; Williamson v. The Alphonso [Id. 17,749]; Winso v. The Cornelius Grinnell [Id. 17,883]. In the case last cited, Mr. Justice Curtis remarks: “It has been strongly urged that both the peril and the service were too slight to bring the case within the technical definition of salvage; but I am not of this opinion. The relief of property from an impending peril of the sea, by the voluntary exertions of those who are under no legal obligation to render assistance, and the eon-sequent ultimate safety of the property constitute a state of salvage. It may be a case of more or less merit, according to the degree of peril in which the property was, and the danger and difficulty of relieving it. But these circumstances affect the degree of the service, not its nature.” The authorities are abundant and decisive on this point. The Independence [Id. 7,014]; The Reward, 1 W. Rob. Adm. 174.

I come now to the consideration of much the most important question in this case, and one upon which the authorities are not very numerous, and, as I view them, not decisive. The claimants insist that, even if the elements of a salvage service were otherwise found in the case, yet the libellant is precluded from salvage compensation on the ground that, during the whole period of peril and of the performance of the service rendered, he was a passenger. The very able argument of the advocate for the claimants proceeds upon the ground that the connection of the libellant with the ship as passenger was not dissolved prior to the performance of the service, and that, as the relation of passenger imposed upon him the duty of aiding in the relief of the ship from the common peril in which he was involved with the rest on board, the law does not recognize him as a salvor. If this point is well taken, it is a complete answer to the libellant's claim for salvage compensation. The principal cases relied on to support this position are The Branston, 2 Hagg. Adm. 3, and The Vrede, 1 Lush. 322. The report of the ease in 2 Hagg. Adm. is in these words: “This brig, homeward bound, got into distress, and a lieutenant of the royal navy, a passenger on board, contributed his assistance and claimed to be remunerated. Per Curiam: When there is a common danger it is the duty of everyone on board the vessel to give all the services he can, and more particularly this is the duty of one whose ordinary pursuits enable him to render most effectual service. No case has been cited where such a claim by a passenger has been established, though a passenger is not bound like a mariner to remain on board, but may take the first opportunity of escaping from the ship and saving his own life. I reject the claim.” The facts in the case of The Vrede, decided by Dr. Lushington, are reported as follows: “The plaintiffs were twenty emigrant passengers on board the Dutch bark Vrede, suing for alleged salvage services to that vessel and her cargo after she had received damage from a collision. The collision took place about five o'clock, a. m. of the 27th of November, 1859, off the South Foreland, and the Vrede sustained great damage, and began to make water rapidly. The plaintiffs manned the pumps, and kept working them. At 7 o'clock a steamtug took the vessel in tow. The passengers continued to work the pumps, and about noon the vessel was safely brought into Ramsgate harbor. The petition alleged that the plaintiffs might have left the Vrede in the boats, or in the steam-tug, but remained on board to work the pumps at the request of the master, and that but for their services the Vrede must have foundered and been lost with her cargo. The answer admitted the facts generally, except as to the extent of the Vrede's danger.” Dr. Lushington, after remarking that although passengers must have often rendered services at sea, yet, except the cases of The Branston and The Salacia [2 Hagg. Adm. 263], no claim had ever before been prosecuted in the admiralty court for salvage, and that this fact was sufficient to put the court on its guard against readily allowing the claim, says: “It is true, as the counsel for the plaintiffs have urged to-day, 81that a pilot or master or ship's crew may sue as salvors in certain circumstances, and so I say that in certain circumstances passengers may also sue as salvors. But it is equally clear that it is only extraordinary circumstances, in the strict sense, which can justify a claim for salvage from persons so related to the ship as the first class of persons I have named. A master cannot he a salvor so long as he is performing his duties as master under his contract; nor can a mariner, until his contract is at an end; nor can a steamtug under a contract to tow make a title, unless, unforeseen dangers arising, she performs different services from those stipulated for in the original contract. With respect to a passenger, there is no engagement on his part to perform any service, but there is a contract between him and the ship-owner that for a certain money payment the ship shall carry him and his property to the place of destination. To a certain extent, therefore, he is bound up with the ship.” Dr. Lushington then proceeds to comment upon the case of Newman v. Walters, 3 Bos. & P. 612, and to distinguish the one before him from it. He says: “The circumstances are not the same, or nearly the same.” After considering the case of The Florence, 16 Jur. 572, and 20 Eng. Law & Eq. 607, where salvage had been awarded to a mate and seaman for services rendered their own ship by them after they had been separated from it, he adds: “That case again is no authority today. I say, that in circumstances such as these, passengers could not claim as salvors. Here the passengers were never separated from the ship, and their only-service consisted in pumping. They pumped first, as they themselves admit, to save their own lives and property. For such efforts in a time of common danger they were not entitled to salvage, by the authority of The Branston. Then the steamer comes up and takes the vessel in tow. I am of opinion, that all danger then ceased, whatever danger might have been. The tug and the pilot-cutter were present; the water was smooth and the weather fine, and a harbor at no great distance. The passengers might, if they chose, have left the ship, but they remained on board and continued working at the pumps. I cannot consider the ship to have been in any danger of sinking, and I think I should be furnishing an evil example if I encouraged suits of this description. I pronounce against the claim of the plaintiffs, but without costs.”

It is obvious that the language of Dr. Lushington in this case of The Vrede is very guarded. There must have been a reason for this, and it is important to understand the extent to which his decision has carried the law, for I should hesitate long before I should pronounce judgment in conflict with the opinion of this eminent jurist In order to arrive at a correct conclusion on this point, we must notice the scope of The Branston as an authority. The latter case is a very simple one. The report is brief, and all that appears from it is that the libellant, a lieutenant of the royal navy, “contributed his assistance while the vessel in which he was a passenger was in distress.” What the nature of that assistance was, or under what particular circumstances it was rendered, does not appear. I conclude that the service rendered was of the ordinary character, and consisted in assisting in working the brig in those ordinary ways well known to seamen. I can draw no other inference from the case, and upon such a state of facts, I think it very clear that any court would have rejected the claim. In the case of The Vrede, the services rendered were also of the ordinary kind, and consisted solely in pumping. I understand it to be a well-known rule that passengers are bound to render all such ordinary aid to the ship when she is in distress. They are bound to man the pumps, the windlass and the ropes, and to assist in working the ship in all ways known to seamen, as far as they may be able. The line of their duty extends, at least, thus far. But the question now before this court is whether there are not extraordinary services which a passenger may render that extend beyond the line of his duty, and which may entitle him to salvage compensation. That this question is not decided in the negative by The Branston or The Vrede is, I think, clear. It has been strenuously urged on the argument that no services that a passenger can render to avert a common danger, while his relation as passenger continues, can exceed the limit of his duty. This doctrine certainly is not laid down in The Branston nor in The Vrede; for in the latter case the learned judge, in the vital part of his opinion, is careful to say: “Here the passengers were never separated from the ship, and their only service consisted in pumping.” Surely, if he intended to lay down the rule that the passengers must in all cases be first separated from the ship before they can become salvors, he would have so declared in terms. The point is so sharp and decisive as to admit of no ambiguity in the language of a judicial opinion. I include in the term separation from the ship, both actual personal disconnection therefrom, and a severance of their ordinary relations as passengers, though they may still remain on the vessel. That there has been, for a long time, a general impression, that a passenger may become a salvor by rendering extraordinary services on board of his own ship, the language of decided cases and text writers abundantly shows. I am aware that this impression can, in many instances, be traced to the influence of Newman v. Walters, but I think it equally true, that it has derived strength, from sound principles. In the case of Newman, 82v. Walters, the ship had struck on a shoal, and the captain and part of the crew had deserted her. The plaintiff took command of her and brought her safe into port. The jury gave him a verdict, and on a motion for a new trial Lord Alvanly, Ch. J., remarks: “Without entering into the distinctions respecting the duties incumbent on a passenger in particular cases, I think that if he goes beyond those duties he is entitled to a reward in the same manner as any other person. In this case the plaintiff did not act as a passenger when he took upon himself the direction of the ship; he did more than was required of him in that situation; and having saved the ship by his exertions, is entitled to retain his verdict in this action.” Language substantially like this is used in various decided cases and by text writers. In several instances the doctrine is discussed and applied to eases where the capacity of a pilot to become a salvor was in question, but this strengthens the principle when applied to passengers. Hope v. The Dido [Case No. 6,679]; Lea v. The Alexander [Id. 8,153]; Hoburt v. Drogan, 10 Pet. [35 U. S.] 108; Abb. Shipp. p. 560; note 1 of Story and Perkins; Marv. Wrecks & Salv. §§ 140, 149: Le Tigre [Case No. 8,281]. The learned author of Marv. Wreck & Salv. p. 160, remarks: “It is agreed, too, that seamen may, while their legal connection with the ship still subsists, earn salvage for services rendered to ship or cargo, exceeding the line of their duty. But there is great difficulty in defining that line, and determining what services are within and what beyond it. No such determination can be made beforehand, and each case must be determined by its circumstances.” In The Neptune, 1 Hagg. Adm. 227, Lord Stowell says: “I will not say that in the infinite range of possible events that may happen in the intercourse of men, circumstances might not present themselves that might induce the court to open itself to their claim of a persona standi in judicio.”

The authorities cited show that officers and crew, pilots and passengers may all become salvors when they perform services to the ship in distress beyond the line of their duty. The duties of passengers are much more circumscribed than those of sailors or pilots; and it would seem that all the law imposes upon them is to assist in the ordinary manual labor of working and pumping the ship, under the direction of those in command of her. If they assume extraordinary responsibilities, and devise original and independent means by which the ship is saved, after her officers have proved themselves powerless, I see no reason, and know of no authority that can prohibit them from being considered as salvors. I think it follows, from the principles laid down by the authorities (1) that a passenger on board a ship can render salvage service to that ship when in distress at sea; (2) that in order to do this he need not be first personally disconnected from the ship; but (3) that these services, in order to constitute him a salvor, must be of an extraordinary character and beyond the line of his duty, and not mere ordinary services, such as pumping and aiding in working the ship by usual and well-known means.

That the services of the libellant in the present case were of an unusual character cannot be denied. After the officers of the ship had exhausted their means of getting control of the rudder, he devised, and with the aid of a large number of men put under his directions by the captain, executed a plan which, in the judgment of this court, was the efficient means of rescuing this great vessel from peril. The whole work of accomplishing this result was intrusted to him, and to his directions. If it is said that he got his main idea of the plan he carried out from witnessing an experiment of the engineer, which I doubt; still the effort of that officer had entirely failed, and was an abandoned experiment. The merit of the libellant in overcoming the obstacles which had proved insurmountable to the engineer is, in my judgment, enhanced rather than diminished by the unsuccessful effort of the latter. That the service rendered by the libellant was a very difficult one is proved by the fact that the able and experienced officers of this ship had failed to accomplish the result which he finally secured. They had spent two days of fruitless effort, though stimulated by motives as powerful as can be addressed to the minds of men. It required no litttle moral courage for the libellant to interpose to arrest the unscrewing of the nut on the rudder shaft, and then assume the responsibility of a new and different experiment, which would consume precious time, and might thus produce appalling consequences. Had he failed, the consequences to him would have been injurious and humiliating. The whole circumstances of the case are so extraordinary, as to leave no doubt in my mind that the services which he performed were wholly beyond his duty as a passenger, and therefore entitle him to salvage compensation. In fixing the amount of compensation it must be considered that, though the service was one of conspicuous merit, and the amount of property saved large, yet the personal danger encountered by the libellant was not very great; and the only things contributed by him were personal skill and labor. He supplied no materials and risked no property, though his labors were protracted and exhausting. On the other hand, he rescued the ship from great peril by his own ingenuity, courage and skill. That the peril of the ship was great, and her position critical in the judgment of her commander, is evident from the fact that he intrusted to this stranger a work, upon the success of which her salvation depended, and which for nearly two days had utterly baffled him and his engineers. The case is so novel a one, in all its leading features, that little light can be derived from 83precedents to guide me in fixing the amount to be awarded; but I have concluded, on the whole, to allow fifteen thousand dollars. Let a decree be entered for the libellant for that amount with costs.

NOTE. After the hearing was concluded and after the decision was published, there were various comments made thereon, which, as they contain some facts that were unnecessary to be set forth in the opinion, are printed in the following pages:

The Great Eastern Case.

Mr. Hamilton Towle's Suit for Salvage against the Steamship Co.

How an American Engineer Saved the Ship from Disaster.

The argument in the now celebrated Great Eastern Case in the United States circuit court, before Judge Shipman, on the claim of Mr. Hamilton Towle to salvage compensation, was concluded yesterday. Mr. George T. Curtis and “William Kemble Hall appeared for the libellant, and Mr. William M. Evarts and Joseph H. Choate for the company. The diagram given of the temporary steering-gear invented by Mr. Towle, and the explanation of it, will fully illustrate the mechanical merits of the case. The historical facts in regard to it are as follows: On the 10th of September, 1861. the Great Eastern left her moorings in the river Mersey, the pilot leaving her at 4 o'clock on the afternoon of that day. Putting on full speed she continued on her course, everything going on well until 4 o'clock on the afternoon of Thursday, the 12th, when it was discovered by accident that she would not obey her helm. A strong gale was prevailing at the time, and an attempt on the part of the captain to steady his ship while the tackle of one of the boats was repaired led to the discovery of the fact that the rudder was unmanageable. The fore-staysail was run up, but the wind split it into ribbons; the fore-trysail was then run up, but was blown away, and the engines were stopped while the boat was cut away. The vessel at length started again, and the passengers went down to dinner. “From that moment,” according to the accounts of those on board at the time, “commenced a chaos of breakages, which lasted without intermission for three days. Everything breakable was destroyed. Furniture fittings, services of plate, glasses, piano, all were involved in one common fate. About six o'clock the vessel had to be stopped again to secure two rolls of sheet lead weighing some hundred weight each, which were in the engine-room, rolling about with every oscillation of the vessel with fearful force. These having been secured, another start was made, when a tremendous grinding was heard under the paddle-boxes, which had become twisted and the floats were grinding against the side of the ship. The paddles were stopped, and thenceforward the scene is described as fearful in the extreme. The ship rolled so violently that the boats were washed away. The cabin, besides undergoing the dangers arising from the crashes and collisions which were constantly going on, had shipped, probably through the port holes, a great deal of water, and the stores were floating about in utter confusion and ruin. Some of the chandeliers fell down with a crash, a large mirror was smashed into a thousand fragments, rails of bannisters, bars and numerous other fittings were broken into numberless pieces. The luggage of the passengers, in the lower after cargo space, was lying in two feet of water, and before the deliverance of the ship was effected the luggage was literally reduced to rags and pieces of timber. Twenty-five fractures of limbs occurred from the concussions caused by the tremendous lurching of the vessel. Cuts and bruises were innumerable. One of the cooks on board was cast violently, by one of the lurches, against the paddle-box, by which he sustained fearful bruises on the arms, putting it out of his power to protect himself. Another lurch drove him against one of the stanchions, by which concussion one of the poor fellow's legs was broken in three places. The baker received injuries of a very terrible character in vital parts; and one of the most striking incidents of the disaster was this poor, brave man, crawling in his agony to extinguish some portion of the baking gear which at that moment had caught fire.” Something must be devised by which the ship could be steered, if she was to be brought to land in safety, and at this juncture Mr. Hamilton Towle, an American engineer, who was a passenger on the vessel, constructed the steering apparatus, by which it is claimed the vessed was saved. Mr. George T. Curtis, in the commencement of the argument, submitted his points to the court, claiming that the vessel laying entirely unmanageable in the trough of a heavy sea, with her rudder-shaft broken below both tillers, her paddle-wheels destroyed, her boats and part of her sails and her after stern-post carried away, and her whole internal condition disordered by the rolling incident to a structure of her enormous size, under the circumstances in which she was placed, and, consequently, that she was in a great and imminent peril of being totally lost, unless some means could have been devised and put in execution for effectually controlling her rudder, so as to take the ship out of the trough of the sea, and then to steer by means of the rudder, the ship could not have been saved, but must have drifted indefinitely at the mercy of the winds and waves, or have become disintegrated and foundered, she being incapable of being towed by any steam or other vessel likely to have fallen in with her.

The following points state that Mr. Towle prevented the unscrewing of the nut on the broken stump of the rudder, by which the rudder was sustained; that he restored the nut to its place by his personal exertions and labor, rendered under circumstances of great personal exposure; that he devised and put into operation at great personal exposure and risk the only competent steering gear by which the ship was safely directed; and that finally the services of the libellant were salvage services of the most meritorious character; and as the ship was of great value, and there were about eight hundred lives rescued from the peril to which the ship was exposed, the libellant is entitled to a large salvage compensation.

Mr. William M. Evarts occupied the session of the court on Monday in presenting the argument of the owners, claiming that the services rendered by the libellant, although meritorious, did not in any sense partake of the nature of salvage services, because he claimed the vessel was neither abandoned nor had the relation of passengers to the officers of the ship essentially Changed, as in the case of a ship being captured by mutineers. The steering gear, he also claimed, was valuable only in connection with the gearing arranged by the officers of the ship around the rudder.

Yesterday Mr. George T. Curtis replied for Mr. Towle in an eloquent and able argument, re-asserting the points previously laid down and elucidating new ones in favor of Mr. Towle's claims. He dwelt upon the inadequacy of the attempts of the officers to steer; upon the partial removal of the nut from the broken rudder-post, and the necessity of retaining it, which was urged by Mr. Towle, who finally screwed it up by a peculiar process: that Mr. Towle designed and constructed the steering apparatus by means of which she was brought to port in safety. In regard to heroism as a feature in the case, he spoke of the danger incurred in arranging the gearing, and the fact of a man being killed and others wounded at the wheel and elsewhere. The argument throughout was full and comprehensive.

Anonymous. 84 From the New-York Times:

Written by Robert D. Benedict, Esq., of the Admiralty Bar of New-York.

The Great Eastern Salvage Case.

We publish this morning, at length, Judge Shipman's opinion in the suit brought by Hamilton E. Towle against the steamship Great Eastern, to recover salvage for repairing her rudder, the shaft of which had been broken in a storm at sea. As will be seen, the judge decrees that he recover $15,000 salvage. The case is one of great interest. That it is connected with the Great Eastern would of itself increase the interest felt in the case, whether here or in England, for anything that relates to that enormous ship attracts attention which would not be felt where any other vessel in the world is concerned. Then again, all our sailors and shipping men have some national feeling in it. That an American passenger on board an English steamer should have been able to devise means of remedying the disaster occasioned by the breakage of that rudder-shaft, after the officers of the vessel had tried in vain to accomplish it, is felt to be something of a national advantage over John Bull, and almost everyone who is interested in shipping will feel glad to have that advantage confirmed by the decision of a court in Mr. Towle's favor. The case is also one of intrinsic importance. It was sharply contested on questions of fact and questions of law. On behalf of the vessel, it was urged very strongly that Mr. Towle was a passenger on board the vessel, and that it was the rule of the admiralty courts that a passenger could not recover salvage for services performed while the relation of passenger still existed. Judge Ship-man examines the authorities on this point, and comes to the conclusion that the true rule is, that a passenger may recover salvage for services rendered by him to the vessel on which he is a passenger, provided those services are not mere ordinary services, such as pumping or aiding in working the ship by usual and well-known means, but are of an extraordinary character and beyond the line of his duty. This principle being settled, there seems to be little difficulty in arriving at the conclusion that Mr. Towle was entitled to recover salvage. The ship was in great peril. Her paddle-wheels were disabled, so that she was dependent upon her propeller engine; her rudder-shaft was broken off so that she could not steer, and she lay in the trough of the sea for about thirty-six hours, during which time her officers had made repeated efforts to devise some means of steering the vessel, but in vain. Mr. Towle then, with the consent of the captain of the vessel, took hold of the affair and carried out a plan which he had already devised for steering the vessel, by means of which the ship was carried out of the trough of the sea and carried in safety into port. Such services as these are clearly not the ordinary services which it is the duty of every passenger to render to a vessel. A passenger might be required to pump, to pull and haul, or to do any other act under the direction and authority of the officers of the vessel; but to take charge and responsibility, to plan and to oversee the execution of his plan—these are clearly extraordinary services, within the meaning of the cases. If not, they might be required of every passenger. But no one would claim that it was the duty of every passenger on board the Great Eastern, even if ordered by her officers, to have devised means for repairing that broken rudder-shaft, or to have put those means in execution. Ordinary services they would be bound to render. Those which they would not be bound to render must be extraordinary. As to the amount of the salvage decreed, it is not large in comparison with the value of the property, the vessel being worth at least half a million dollars. And if anyone thinks that Mr. Towle is pretty well paid for his day and a half of labor, let him think of the responsibility which he would have had to bear in case of failure.

The opinion is a long one, but it will be read by many who are interested in navigation both here and abroad, and may excite some comment in England, unless indeed they have become weary of the great ship and of everything connected with her.

From the London “Law Times” of January 28, 1865, page 146:

Unmerciful revealers of things kept secret are law courts. In many instances circumstances which, at the time of their occurrence, are of as great interest to the public as the law point which afterwards arises upon them is to the profession, first see the light in our reports. In 1861, when the success of the Great Eastern steamship was still in the balance, she left Liverpool on the 10th of September for New-York. She carried 400 passengers and a considerable cargo, with about the same number as officers and crew, including engineers and others below. It was hoped, as she started, that she would still retrieve the misfortune which had befallen her off the Devonshire coast. But in a few days she came back disabled into port. It became known to the public that, when she was about 300 miles west of Cape Clear, she encountered a heavy storm in the night of Thursday, the 12th, which swept away her paddle-wheels and some of her boats, and that as, with her rudder rendered useless, she lay in the trough of the sea rocking from side and side, her cabin furniture was broken up, and the luggage in the hold drenched and crushed into a mass of rubbish. But the real amount of the danger, which in fact became so great that it was a providential thing that she was ever seen again, was not allowed to transpire. What happened was this. When the force of the sea against her great bulk in one direction, and its strain in the opposite direction against her rudder had twisted the rudder pillar in two, like a piece of stick, so that part remained attached to the steering gear while the blade swung idle in the water, the officers of the ship made repeated attempts, between Friday morning and Saturday afternoon, to get control of the ship's motions. These attempts all proved fruitless. A further attempt made by the chief engineer, and commenced by unscrewing a nut which contributed to support the weight of the lower part of the rudder, threatened to make the case hopeless. It was denounced to Captain Walker by one of the passengers, and was ordered to be discontinued. Then the captain lost all confidence in the chief engineer, and, for aught that appeared, the vessel must be left to her fate. But this passenger, Mr. Hamiliton E. Towle, was himself an engineer of considerable experience. Immediately after the mishap occurred he revolved in his own mind the plan of a remedy, drew a sketch of it, and showed it to the chief engineer, but was repelled with rudeness. Captain Walker, however, having exhausted his own expedients and those of his officers, and being alarmed for the ship's safety, decided that Mr. Towle should try his plan, and placed men and materials at his disposal for the purpose. At five o'clock on Saturday afternoon Mr. Towle set to work, screwed up the nut with great labor, and principally by means of an immense chain of sixty pounds to the link, (brought from the forward part of the ship,) which was let down into the steerage deck through a hole cut in the upper deck, and was wound round the cone of the lower part of the rudder, with its ends fastened to posts in the steerage deck, Mr. Towle, after working all Saturday night, at five o'clock on Sunday afternoon enabled the ship to be brought up to the sea and put on her course. The legal question was Mr. Towle's right to salvage for his service. It was decided in the United States admiralty district court, by Judge Shipman. Towle v. The Great Eastern, 11 L. T. (N. S.) 510. The difficulty in the case arose from the 85incident that Mr. Towle was a passenger in the ship, the subject of the salvage. Had Mr. Towle fallen in with the ship thus disabled and in the power of the sea and gone from his own ship, and rendered these services, there would have been no question of his right as a salvor. The authorities, the judge said, were abundant and decisive on that point. But in the case of The Branston, 2 Hagg. Adm. 3. where the claimant, a lieutenant in the navy, being a passenger on board the brig in distress, contributed assistance, the court held, that where there was a common danger it was the duty of everyone on board to give all the services he could, and more particularly of one whose ordinary pursuits enabled him to render most effectual service. A passenger might, if he could, leave the vessel. The Vrede, 1 Lush. 322, was decided on the same principle. After a collision, the claimants, emigrant passengers, manned the pumps until the vessel was towed into Ramsgate harbor. Dr. Lushington was of opinion that there being, under the circumstances of the case, no danger, and the claimants not choosing to leave the ship, as they might, by means of a tug and pilot cutter which were present, but remaining to work, were not entitled. As to the stronger of these two cases (The Branston), Judge Shipman concluded that the service rendered by the lieutenant was of the ordinary character, and consisted in assisting in working the brig in those ordinary ways well known to seamen. But the present question, whether there were not extraordinary services which a passenger might render that extended beyond the line of his duty, and might entitle him to salvage compensation, was not decided in the negative by The Branston or The Vrede. The authorities showed that officers and men, pilot and passengers, might all become salvors when they performed services to the ship in distress beyond the line of their duty. I think,” said the judge, “it follows from the principles laid down by the authorities, first, that a passenger on board a ship can render salvage service to that ship when in distress at sea; secondly, that, in order to do this, he need not be first personally disconnected from the ship; but, thirdly, that these services, in order to constitute him a salvor, must be of an extraordinary character and beyond the line of his duty, and not mere ordinary services, such as pumping and aiding in working the ship by usual and well-known means.” Accordingly the judge decided in favor of Mr. Towle's claim, and, putting the value of the Great Eastern at five hundred thousand dollars, awarded to him fifteen thousand.

1 [From a pamphlet report prepared by and furnished for publication through the courtesy of the Honorable William D. Shipman, formerly United States district judge for the district of Connecticut. This pamphlet report contains the following prefatory note:]

The following case has never been published in this country, except in newspapers, though it appeared soon after it was decided (Towle v. The Great Eastern, 11 Law T., N. S., 516) in England, and subsequently in 2 Marit. Law Cas. 148. It was earnestly contended on the hearing by the eminent counsel for the claimants that there was no well settled authority for allowing a passenger salvage under such circumstances as those which characterized the services rendered by the libellant. As the doctrine laid down by the court in deciding the case was, by some, considered novel and the amount involved considerable, it was hoped and expected by the court that the case would be carried by appeal to the supreme court of the United States; but no appeal was ever taken. The opinion is now reprinted from the New-York Times, and is a verbatim copy of that opinion originally delivered and filed by the court The illustrations used on the trial, which have never before been published, will be found in Appendix No. 1. [See statement.] It is said that since the decision, Judge Cadwalader, of the Eastern district of Pennsylvania, in an analogous case, followed the same rule as that laid down in this of The Great Eastern. The interest taken in the case at the time by those engaged in maritime affairs, as well as by the admiralty bar, and the increase of ocean steamships will probably justify this republication. W. D. S. February 28th, 1893.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.