Case No. 13,700.

SWIFT et al. v. WHISEN et al.

[3 Fish. Pat Cas. 343; 2 Bond, 115; Merw. Pat. Inv. 426.]1

Circuit Court, S. D. Ohio.

Oct. Term, 1867.

PATENTS—ASSIGNEE—REISSUE—FRAUD IN PROCUREMENT—OMITTED CLAIMS—DRAWINGS—EXTENSION—FOREIGN INVENTION—EXPERIMENTS.

1. A reissue may be granted to an assignee of an assignee of letters patent.

2. A reissue may be granted to an assignee, upon his application, without the consent, approbation, or knowledge of the original patentee.

3. It is the uniform doctrine of all the courts of the United States that they will presume that the law has been complied with; and they refuse to go into any inquiry, back of the grant by the commissioner, except in cases of fraud.

4. If facts appear which are sufficient to satisfy the jury that there has been fraud in the procurement of the reissue, either actual fraud, or circumstances which may be supposed to amount to constructive fraud, the reissued patent will be void.

5. There may be a constructive fraud, where it is made manifest that the reissued patent is fraudulently extended beyond the claims of the original patent for a deceptive purpose.

6. If a certain feature of the original invention was the invention of the patentee which he omitted to claim in his specification and claim, upon the surrender of the patent, by himself or an assignee, he has a right to incorporate that element in the claims for a reissued patent.

7. If the drawings show an element of the invention which the patentee has not included specially in his claim, it is evidence, nevertheless, that it was a part of his invention, and he or his assignee has a right to incorporate that element in a reissued patent.

8. The fact that the original patent has been reissued three times, and that the original patent had been thus three times submitted to the investigation of the patent office, would be a presumption in favor of the fairness of the transaction.

9. Upon an application for an extension of a patent, the law requires a very rigid scrutiny into the original claim of the patentee as to the novelty and utility of the invention.

[Cited in Cook v. Ernest, Case No. 3,155.]

10. An extension strengthens the presumption of the novelty and utility of the patent.

[Cited in Cook v. Ernest, Case No. 3,155.]

11. Courts are reluctant to declare a patent void on the ground of vagueness or ambiguity, unless it be very clear and unmistakable.

12. A claim for a bolt to be placed in a position, “vertical or nearly so,” is free from ambiguity. It calls for a bolt in a vertical position, with permission to the builder to give it a slight inclination if necessary, in his discretion.

13. In all descriptions of patented machines, something must be left to the judgment and discretion of the mechanic who constructs tie machine.

14. An ambiguity in the description may be removed by reference to the drawings, which may be examined to determine the dimensions of the parts, when dimensions become material.

15. All the parts of a combination must co-act in producing the result claimed from their combination.

16. If a machine be invented and used in a foreign country, but not patented or described in any publication or work, such use will not affect the right of a bona fide American inventor to a patent.

17. There is no kind of testimony that is more reliable in regard to the true character of a machine than an accurate model; it is a witness that can not lie.

18. If a machine, although designed to separate smut from wheat, embodies the principle of a machine afterward patented to separate flour from bran, and, without the exercise of invention, could be changed so as to perform the same functions as the latter, in substantially the same way, the patent would be void.

19. If a prior machine were merely got up for the purpose of experiment, and was not practically tested, it would not constitute a practical invention.

This was an action on the case [by Alexander Swift and Joseph Kinsey against Amos Whisen, and Jesse Green, and others] tried before the court and a jury, brought to recover damages for the infringement of letters patent [No. 6,148] for “improvement in machinery for separating flour from bran,” granted to Issachar Frost and James Monroe, February 27, 1849, reissued to them March 13, 1855 [No. 302], assigned to H. A. Burr, J. D. Condit, A. Swift, D. Barnum, and J. M. Carr, and reissued to the assignees May 11, 1858, assigned to Alexander Swift and reissued to him February 25, 1862, extended to the original patentees, upon their application, for seven years from February 27, 1863, and on the same day assigned to the plaintiff.

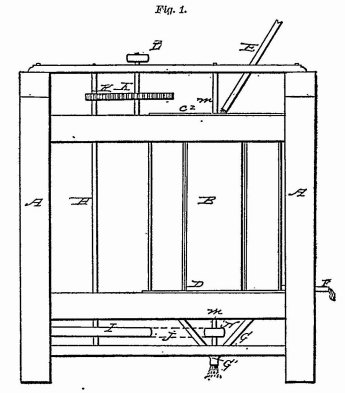

The disclaimer and claim of the original patent were as follows: “Having thus fully described the construction, arrangement, and operation of the several parts of our machine, we will now add that we do not mean to claim to be the original Inventors of a cylinder, nor of a combined punched and reticulated cylinder, nor of a cylinder covered with strips of punched sheet iron and strips of leather filled with tacks, such as are used in smut machines, nor the arrangement of gearing by which the machine is propelled; but we do claim to be the original and first inventors of the combination and arrangement of the external upright stationary close cylindrical case B, with the internal combined punched and reticulated upright stationary scourer and bolt B1, B3, and revolving cylindrical scourer and blower C, constructed, arranged, and operated in the manner and for the purpose herein fully set forth, by which the fine flour that usually adheres to the bran, after being subjected to the first bolting operation, is now completely separated from the bran and collected in the annular space between the cylindrical bolt and cylindrical case, from whence it descends through the segmental openings in the horizontal base, upon which the said bolt and case rest, into conducting spouts as 564aforesaid, whilst the bran is blown from the interior of the bolt through a spout leading through the external case as aforesaid, in the meshes of the bolting cloth, being kept open by the pressure of air produced inside the combined cylindrical scourer and bolt, by the manner in which the oblique and radial and parallel wings are arranged on the revolving, scouring, and blowing cylinder, as above set forth.”

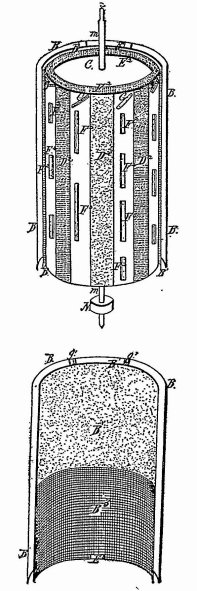

[Drawings of patent No. 6,148, granted February 27, 1849, to Frost & Monroe; published from the records of the United States patent office.]

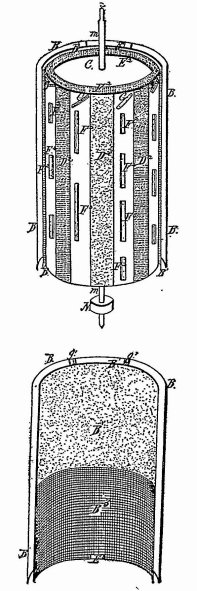

The claims of the reissue of 1855 were as follows: “I claim, first, the platform D (always at right angles with the sides of the bolt when not made conical), or close horizontal bottom, when used in connection with upright stationary or revolving bolt for flouring purposes. Second. The openings at D5, for the admission of a counter current of air through the bottom and into the bolt, and the opening and bran spout F, as described in combination with the platform D. Third. The upright stationary bolt and scourer combined with its closed-up top, except for air and material; or, in combination with claims first, second, and fourth, or either of them, or their equivalents, to produce like results in the flouring process. Fourth. The use of the revolving, distributing, scouring, and blowing cylinder of beaters and fans, by which the material is distributed, scoured, and the flour blown through the meshes of the bolting cloth.”

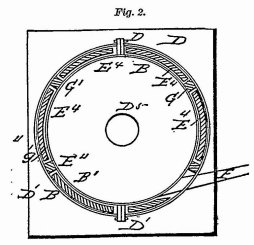

The claims of the reissue of 1858 were as follows: “We claim, first, the vertical, or nearly vertical position of the bolt. Second. A surrounding case forming a chamber or chambers round the bolt, substantially as and for the purpose specified, and provided with suitable means for the delivery of the flour, as specified. Third. A rotating distributing head at or near the upper end of the bolt, substantially as described. Fourth. Rotating beaters or fans within the bolt, substantially as and for the purposes specified. We also claim, in combination with the first, second, and fourth features of the combination first claimed, the closed-up top of the bolt, except an aperture or apertures for the admission of the material and air, substantially as and for the purpose specified. We also claim, in combination with the first, second, and fourth features of the combination first claimed, the closed-up bottom of the bolt proper, except an aperture or apertures for the discharge of the bran, substantially as and for the purpose specified, whether the said bottom be or be not specially provided with an aperture or apertures for the admission of air as specified. We also claim, in combination with the third combination claimed, or the equivalent of the features thereof, the employment of rotating arms, or wings, moving in close proximity with the inner surface of the closed-up bottom, substantially as and for the purpose specified. And finally, we claim the combination of all the features herein specified as essential features, substantially as described, or any equivalents for any or all the said features.”

The reissue of 1862, which was granted to Alexander Swift, upon his application, described seven essential features of the invention, which were substantially as follows: (1) The vertical or nearly vertical position of the bolt; (2) the surrounding case, forming a chamber outside of the bolt; (3) the rotating cylinder armed with beaters, pins, or fans; (4) the distributing head on the top of the rotating cylinder; (5) the closed-up top to the bolt proper; (6) the closed-up bottom to the bolt proper; and (7) rotating wings or bran scrapers to clear the bottom 565of the bolt and discharge the bran. The claims were as follows: “First. The combination of the essential features severally described and severally numbered 1, 2, 3, and 4, or their equivalents, substantially as described; and for the purposes specified in the several numbers. Second. The combination of the essential features severally described and severally numbered 1, 2, and 5, or their equivalents, substantially as they are described; the purpose of the combination being substantially as set forth in number 5. Third. The combination of the essential features severally described and severally numbered 1, 2, and 6, or their equivalents, substantially as they are described; the purpose of the combination being substantially as set forth in number 6. Fourth. The combination of the essential features severally described and severally numbered 1, 2, 6, and 7, or their equivalents, substantially as they are described; the purpose of the combination being substantially as set forth. Fifth. The combination of the essential features severally described and severally numbered 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, and 7, or their equivalents, substantially as described; the purpose of the combination being substantially as severally set forth.”

[Drawings of reissued patent No. 302, granted March 13, 1855, to Frost & Monroe; published from the records of the United States patent office.]

A. F. Perry and S. S. Fisher, for plaintiffs.

G. K. Sage, E. B. Forbush, and E. W. Stoughton, for defendants.

LEAVITT, District Judge (charging jury). This suit is brought, gentlemen, by the plaintiffs, Swift & Kinsey, against the defendants, charging an infringement of a patent of which they claim to be the owners or proprietors, which was originally issued to Frost & Monroe, February 27, 1849, purporting to be for a new and useful improved machine for separating flour from bran, and designated as a bran duster. The plaintiffs assert their ownership to this patent by assignment. There have been three reissues upon this original patent: The first was on 566March 13, 1855, upon the application of the original patentees, Frost & Monroe. They surrendered the patent and obtained the reissue with an amended specification. The patent seems, then, to have been assigned by the original patentees to Burr and others, and on May 11, 1858, was again surrendered and a reissued patent was granted to those assignees. They assigned the patent, it would appear, to one Alexander Swift, and it was reissued to him on February 25, 1862, and this last reissued patent was, on February 27, 1863, extended to the original pattentees, on their application, for the term of seven years, and by them assigned to Swift & Kinsey, the present plaintiffs. The extended term has not yet expired, and of course the patent is still in force. It will expire in three years—a little more than three years—when the improvement will be free to the public, without let or hindrance.

There are several grounds of defense to this action, to which I propose, very briefly, to call your attention. And the first involves a legal question or proposition, viz: that the reissue is void for several reasons, to which I shall advert hereafter. In the second place, that the invention, the original invention of Frost & Monroe, was not a new one, and therefore not patentable, and not having the character of novelty, the patent itself is void. Then, in the third place, the infringement of this patent is denied by the defendants. These are the issues, gentlemen. The two last are issues of fact; that is, the novelty of this invention and the question of infringement, upon which you are to pass upon the evidence adduced. The questions as to the validity of the reissue are for the court, and upon these questions—for there are several of them—I propose to state my conclusions, very briefly, however, not intending to go into an elaborate discussion of these propositions, some of which are very important and very interesting. For the purposes of the present trial it is unnecessary. All that the jury and the parties want upon these questions of law, is a mere statement of the conclusions of the court, and then, if the views stated by the court are erroneous, the counsel know very well how they can avail themselves of the remedy, and take the proper course to correct the errors. But, of course, it would not be expected of me, that upon these questions of law which have been submitted and extensively argued, I should present to the jury an elaborate exposition, with a reference to all the authorities; there is no necessity that I should detain the jury by such an exposition. I proceed, therefore, to refer to the points raised.

The first is, that this reissued patent, upon which these plaintiffs sue, is void because the right of reissue was not assignable to Alexander Swift; that, in short, an assignee of an assignee has no right, under the law, to surrender a patent and obtain a reissue. It is admitted, by the learned counsel for the defendants, that the immediate assignee of the patentee could make a valid surrender and a valid patent could be issued to him. He claims, however, that a second or third assignee can not make a valid surrender, because the statute does not give the right to such an assignee to make a surrender of the patent. No authority was cited by the counsel in support of this proposition; nothing to show that there was any such limitation upon the right of surrender and reissue of a patent as the counsel claim. There was a reference merely to an opinion delivered many years ago, by the late Chief Justice Taney, when he was attorney general of the United States, during the administration of General Jackson. But this decision, or opinion, is not judicial authority; it is not the action or decision of any court, and therefore not obligatory upon this court. If the point had been before the supreme court of the United States, and had been decided there, it would have been imperative upon this court to follow it, to adopt it as the law of the case. But no such decision has been referred to, and I am not aware that any such exists. The thirteenth section of the patent act of 1836 [5 Stat. 122] is relied upon as sustaining the proposition urged by the learned counsel for the defendants. I will not trouble you to read this section, for it has been repeatedly read in your hearing, and it may be presumed that you are familiar with its main provisions. That section authorizes the surrender of a patent where the description of the invention is defective or insufficient, and the error has arisen from inadvertence, accident, or mistake, and without any fraudulent or deceptive intention, and the same section contains a provision giving this right of surrender and reissue to executors and administrators when the patentee is deceased, and to assignees. There is nothing, therefore, in the terms of the statute, which limits the right of reissue to the patentee or first assignee. So far as the statute is concerned, there may be, at least by strong implication, a right of reissue by subsequent assignees. And it is very well known that this is the construction which has been uniformly given to this statute by the patent office. There are, as was observed by counsel, a large number of patents now in force, having full validity, and patents, too, of the greatest public interest and importance, that have been second and third reissues, and it is every day's practice thus to grant these reissues. And here I am called upon to remark that the doctrine and principles involved, and to which I am now calling your attention, have been adjudicated upon in this court by my learned brother, Judge Swayne, who, when present, is the presiding judge of this court, and to whose opinion upon all legal questions I always yield a most implicit respect. This point was before 567him, was fully argued, and it was held that a reissue to a second assignee was valid.

The next point urged as an objection to the validity of this reissued patent is, that the original patentees, if living, must join in the surrender of the patent and the application for a reissue, and that a reissue to an assignee, without the concurrence and approbation of the original patentee, is void. This objection, too, is covered by the decision to which I have referred, made in this court by my learned brother, Judge Swayne. And in reference to this point, too, I may observe that the practice of the patent office at Washington has been uniform. So far as I know and am informed, it has been the practice of that department, ever since the enactment of the law of 1836, to grant reissued patents to assignees without requiring the concurrence and assent of the original patentee. And thus, as I remarked a little while ago, there may be thousands of patents in the United States that have been issued under these circumstances; they have been reissued upon the application of an assignee or assignees of a previous assignee. And it would be obvious to the jury that the result of a contrary doctrine, under existing circumstances, would be exceedingly injurious to the public interest, as the effect would be to invalidate all the patents that have been reissued under the circumstances to which I have adverted. And, as there is no limitation, there is no provision in the act which denies to assignees this right of surrender and reissue; no provision requiring that the patentee should assent to the reissue, and there is no necessity devolved upon the court to declare that the grant of such a reissue by the commissioner of patents is unauthorized. And without going further into this question, I may say that until the supreme court of the United States shall have had this point before them, and shall have decided adversely to the usage and practice of the patent office and the views to which I have referred, I shall feel compelled to regard the statute as authorizing a reissue to an assignee of an assignee, and that without the consent, or approbation, or knowledge of the original patentee. If he is dead, of course his consent and approbation can not be procured; the statute is express in declaring that the reissue may be to the executor, or administrator, or to the assignees—the holders and owners. It is very true that there are some considerations that would operate in the mind of a judge, if it were a new question, in the other direction, and to the effect that, unless the application for the reissue was made with the knowledge or consent of the original patentee, a second or third reissue should not be valid. There does seem to me some inconsistency in requiring the assignee, in sustaining his application for a reissue, to go before the commissioner and to make bath in regard to the invention covered by the reissue, and to show that it is the same invention covered by the original patent. But, as I said before, there is no prohibition in the statute to this effect, and, as there are no judicial decisions to the contrary, and as it has been the uniform usage of the patent office to grant reissues under these circumstances, the court would not now feel authorized to say that the patent in question, the patent upon which you are to pass, is invalid upon the ground referred to.

The third legal question raised and relied upon by the counsel for the defendants is, that this patent is void as being for a different invention from that covered by the original patent to Frost & Monroe. There is no question, gentlemen, that section 13 of the statute to which I have referred does require that the reissue shall be for the same invention covered by the original patent But the statute makes it the special duty of the commissioner of patents to examine closely every application for a reissue, and he is vested with no authority to grant a reissue except under circumstances where the statute has been complied with. It is to be supposed, in support of the exercise of the authority of the commissioner of patents under the law, that all the requisites of the statute have been complied with, and hence it is the uniform doctrine of all the courts of the United States, that they will presume that the law has been complied with, and they refuse, except under special circumstances referred to in the act, to go into any inquiry back of the grant, by the commissioner of patents, of these reissues; in other words, to a certain extent they consider the action of the commissioner upon the right of parties to a reissue to be conclusive, presuming that all the requirements of the law have been enforced, have been complied with, in the case. The decisions upon the general doctrine to which I have referred, namely, to the effect that the action of the commissioner is conclusive upon the question of the identity of the inventions embraced or described in the reissue and in the original patent, would seem to be harmonious. There is no case, that I am aware of, in conflict with this general proposition, and these decisions rest upon the fact that in deciding whether the reissue is for the same invention, the commissioner of patents, who acts, of course, under the obligation of an oath, acts in that particular in a judicial capacity. His decisions, therefore, on points of that kind, have the force and effect of judicial decisions, and courts are reluctant to go back of those decisions and to inquire whether the reissue has been properly granted or not, except in cases where it is made apparent that the reissue was obtained by fraud, or for the purposes of deception and imposition. But if any facts appear in the progress of a trial, which are sufficient to satisfy a jury that there has been fraud in 568the procurement of a reissue, either actual fraud, or circumstances which may be supposed to amount to constructive fraud the reissued patent will be held invalid. There is a plain distinction between actual fraud and constructive fraud. The statute refers, specially, to cases of collusion—fraudulent, corrupt collusion between the applicant for the patent and the commissioner of patents. If it is apparent that there has been any improper collusion between them, and that the patent has been granted corruptly, then of course, that is an act of positive fraud that will invalidate any patent to which it applies. And there may be also constructive fraud, where it is made manifest that the reissued patent is fraudulently extended beyond the claims of the original patent for a deceptive purpose, for the purpose of imposition upon the public, and where there is no just foundation for such a claim in the original patent; where, in fact, the reissue goes altogether beyond the scope of the original invention and incorporated an element that was not contemplated or intended by the original patentee in his original patent. Cases of this kind have occurred in the progress of the execution of the patent laws of the country where reissues have been fraudulent; that is, where they have been tainted with this constructive fraud; where it appeared that, for a deceptive purpose, a party applying for a reissue had sought to embrace an element in the reissued patent that was not claimed and did not pertain to the original invention, for the purpose of taking advantage of other parties in the community who were using that element which he had fraudulently made a pail of his original invention. It will, therefore, be competent, in my judgment, for the jury to inquire in the present case, whether there is anything that will amount to constructive fraud on the part of the last assignee in the obtainment of the reissued patent upon which this action is founded. Some decisions of the courts, perhaps, go to the extent of saying that even this is a proper inquiry for the court, and not to be submitted to the jury. My strong inclination, however, is to the opinion that this question may be fairly left to the jury for their decision. There is no claim, in the present case, that there was any actual fraud in the obtaining of this reissue, and the only ground upon which it is asked that the jury should presume fraud, as claimed by the counsel for the defendants, is the fact asserted by them and insisted upon, that the claims of the reissued patent are broader than those of the original patent. On this subject, I may remark, in deciding what a party may claim under a reissued patent, there has been a tendency to great liberality in the action of the courts, and it has been held that whatever was the invention of the original patentee, whether expressly claimed in the original patent or not, when incorporated in the reissued patent, will be held to be within the claim of the original patent, and that it is the right of the assignee or holder of the patent to claim everything that was claimed, or everything which belonged rightfully, by fair construction, to the original patentee. I may not be understood. If there is evidence that the original patentee claimed, as a part of his invention, a certain feature, or that a certain feature was a part of his invention, which he omitted to claim in his specification and claim, upon the surrender of that patent by himself, or by an assignee, he has a right to incorporate in the reissued patent that element, though not claimed specially in the first patent. And in determining this question, that is, the substantial identity of the invention covered by the original patent with that covered and described in the reissued patent, it is competent for the jury to look into the drawings of the original patent to determine whether the inventions are the same. The drawings, as well as the specifications, are to be looked to in giving a construction to the claims of a patent, in determining what was the invention of the original patentee. If, for instance, the drawings show an element of the invention which the patentee has not included specially in his claim, it is evidence, nevertheless, that it was a part of his invention, and he or his assignee has a right to incorporate that element in the reissued patent It will be proper, therefore, upon this point, for the jury to look to all the evidence upon the question whether the invention included in the reissued patent is identical with that patented to Frost & Monroe, and in doing this, as I remarked just now, it will be proper for them to look to the drawings and to the evidence of Mr. Knight and Mr. Clough, who, if I remember rightly, stated that the drawings of the original patent to Frost & Monroe were precisely the same as those accompanying the specifications of the reissued patent. It will be proper to remark here that, in my judgment, very clear and decisive evidence would be required in order to invalidate this patent upon allegation of fraud in the reissue. In the first place, the grant of the original patent affords a presumption that it was for something new and useful; that the claim of the patentees had been fully and critically examined by the officers of the patent office, and that upon clear conviction of the rightfulness of the patent it was granted to them. Then the fact that there have been three reissues of this patent, and that the original claim has thus been three times submitted to the investigation of the patent office, would be a presumption in favor of the fairness of the transaction; and lastly, the fact that this patent has been extended for seven years beyond the duration of the period for which it was originally granted. The law upon the subject has been adverted to by counsel. I will not read it, but upon an application for 569the extension of a patent, the law requires a very rigid scrutiny into the original claim of the patentee as to the novelty of the invention, its utility, and whether the patent was fairly granted. The commissioner is required by law to give public notice to all concerned that a hearing will be had before him on the question whether the patent shall be extended or not He is required to investigate the originality and novelty of the invention to ascertain whether the patent, originally, was properly granted, and then he has further to inquire whether the patentee has been sufficiently remunerated by the benefits or the emoluments which he has reaped from it during the period that it has run, and, if satisfied on all these points, then the patent is extended, as this patent has been.

There is another point raised by the counsel for the defendants, and it is that this reissued patent is void for vagueness and uncertainty in the specification. There is an express provision in the statute that every patentee shall define or describe his invention in such full, clear, and exact terms that any mechanic, skilled in that department, would be able to construct the machine, or to make the improvement covered by the patent. It is not controverted in this case, I believe, that a skillful mechanic could take the specifications and the drawings in the original patent and construct the machine, the bran duster, as claimed by Frost & Monroe. And one of the witnesses, Mr. Knight, a gentleman very well skilled in mechanics, has said that the machine could be constructed from the specification and drawings accompanying the reissued patent. But the counsel for the defendants insist that there is a fatal defect that vitiates the patent; first, in claiming the bolt of the machine, or bran duster, as vertical, or nearly so. The argument is that there is such an uncertainty, so much of vagueness and ambiguity, that a machine could not be constructed under it without experiment. Now, in construing the claim of patents, the specifications, and drawings, it has been the usage of the courts of the United States, who are vested with the sole jurisdiction in the administration of the patent law, to exercise great liberality. Courts have avowed it to be a rightful object to carry out, if possible, the purposes of the inventor in the patent which has been granted to him; and unless, therefore, the objection on the ground of vagueness or ambiguity is very clear and unmistakable, courts are reluctant to declare a patent void on this ground. I do not, for myself, see that there is such vagueness in the description referred to, requiring the bolt to be vertical, or nearly so, as would invalidate this patent. I think the clear understanding of every one who reads the patent would be, that while the vertical or perpendicular position was claimed, distinctly and clearly, it was left to the discretion of the builder to incline it in a very slight degree from the vertical position, if he judged that would be the preferable mode of setting the machine. But where the upright position is claimed, distinctly and clearly, as a way by which the machine maybe successfully operated, it does seem to me that the expression “vertical or nearly so,” is free from all ambiguity or vagueness that would invalidate the patent on the ground claimed. It may be remarked here, as it has been very often remarked by judges of much more learning and experience in the patent right law than myself, that in all descriptions of patented machines, something must be left to the judgment and discretion of the mechanic who constructs the machine. It will, perhaps, rarely happen, even where the utmost vigilance and care are observed, that the machine or structure will be so accurately described as that the description can be literally and strictly followed in every particular. The skillful mechanic will see that in some particulars there is some vagueness, and some discretion is required, but that fact will not invalidate the patent.

It is urged, moreover, as a ground of defense to this action—as a reason why this patent should be declared void—that it fails to describe the place or the size of the apertures in what is called the “closed-up top.” One or more apertures, as the jury will recollect, are called for in the specification, and they are required to be upon the inner periphery, if I remember rightly, of the upright cylinder, but the size of those apertures is not described in the specification. It is stated by the counsel for the plaintiff who last addressed the jury, that these apertures, though not especially described in the specification, are nevertheless shown in the drawings. I have not examined the drawings with a view to that point, but if that be the fact, it undoubtedly removes any objection on the ground of vagueness or uncertainty in the description, which might be occasioned by not stating the exact size of these apertures. The jury, on their retirement, can examine these drawings with a view to this question. If they find these apertures are there, with an intimation, from the drawing itself, as to their position and their size, it would undoubtedly be an answer to the objection which has been urged by the counsel for the defendant.

I did not intend, gentlemen, to detain you so long with my remarks, but there are still some other points to be presented. This patent, as the jury will have clearly understood, is for five different combinations of various elements, constituting five different inventions. Now, there is no question but what the law does authorize a patent for inventions of this kind. The jury will observe that there is no claim that any one of the elements of these several combinations is new. The entire claim of the original patentee, and so of the reissues, is that these elements, when combined 570in a certain way, are new, and that in that combination they do produce a new and useful result. If this proposition is sustainable in the minds of the jury, there is no question as to the patentability of the combinations. The object of this invention you all clearly understand, and it is hardly necessary, therefore, to detain you by stating the object, as it is set forth in the specification connected with this reissued patent. They say: “Our invention consists in forming new combinations for producing the results desired and for remedying the defects enumerated in prior machines,” etc. Then follows a minute or full description of the different combinations which are claimed in the reissued patent. Now, to one uninitiated, it is very possible that there would be something unintelligible or not clear in these claims to combination. If I were called upon, as I am unacquainted with practical mechanical science, I should certainly have some difficulty in ascertaining and defining precisely the elements of these five separate combinations. The machine, as a whole, as it is admitted, is undoubtedly a practical and efficient machine. It works well, and the experts who have been examined upon that point have testified to the jury that they find, in the claim of the patent, all the parts and elements of these five several combinations. There are, probably, mechanics upon the jury who will understand this subject better than I do, and who will be able to examine for themselves, and I doubt not the jury will give due credit and weight to the opinions of the learned experts who have testified upon this subject to the effect, as I just stated, that the several combinations are all included in the specifications which accompany the reissued patent. If the jury find, therefore, that these combinations are there, that they are parts of this working and efficient and practical machine, there would be no reason for a conclusion unfavorable to the claims of this patent.

There are two instructions that have just been submitted to the court by one of the counsel for the defendants. I do not know that there is any objection to stating them to the jury. The court is asked to say to the jury that, as a matter of law, all the parts or devices of the combination claimed must co-act to produce a given result in order to form a legitimate combination, and if the jury find that the surrounding case does not co-act with the vertical position of the bolt and closed-up bottom to the bolt proper for the purpose of discharging the bran, as stated in the third claim of the reissued patent upon which this suit is brought, then such claim is void for want of unity and cooperation of its several parts; and the court is requested to charge the same in respect to the combinations of the fourth and fifth claims of the patent. I suppose the entire meaning of this is, that each separate combination claimed by the patentee in the reissued patent must be what it is described to be; that all the parts must be found there, and that all those parts must co-act in producing the result claimed for the combination. That instruction may be given to the jury.

If the jury are satisfied that this is a valid patent—that the various objections to which I have referred do not exist—the next question which will be submitted for their consideration will be the novelty of the invention, as claimed by the original patentees, Frost & Monroe; and here, the inquiry for the jury will be, does the patent describe and claim a combination not before known. Now, it is a very familiar principle with which, no doubt, every juror is perfectly acquainted, that novelty is an essential element of a patented invention; that the law only authorizes a patent for an invention that is new and useful in its result. The presumption of novelty is a presumption arising upon the emanation of the patent itself, and from the fact, to which I have adverted, that the patent has been extended after the rigid and scrutinizing examination of the patent office. But it is still the right of a party sued for an infringement to prove the want of novelty, and if that position is sustained by the evidence, the patent is undoubtedly invalidated. It is a good objection to every patent, that there was no novelty in the invention. This is a question exclusively for the jury. There are two machines here which have been relied upon by the defendants as showing a want of novelty in the invention of Frost & Monroe; to show, in other words, that they were anticipated in the invention which they claim in their patent. The first is the Ashby machine, a machine patented in England to William Ashby in 1846, and prior in date to the patent of Frost & Monroe. If the jury are satisfied, from all the evidence, that that machine, as invented by and patented to Ashby in England in 1846, is substantially identical with that covered by the claims and invention of Frost & Monroe, it would be a full answer to the present action. The law of identity in regard to mechanical structures, I presume the jury are acquainted with. It does not look merely to the form of a structure, or its dimensions, or appearance, but the question is, as has been fully settled by the courts, whether the two involve the same mechanical principle in their operation. Now, this invention of Ashby, if it had not been patented in England, or described in a foreign publication, even if the jury should be of opinion that it was identically the same machine covered by the Frost & Monroe patent, would be no bar to their patent. If, for instance, Ashby had merely invented a machine, but had never patented it, and it had not been described in any publication or work in that country, a man here, who had, by his invention, discovered the same machine, would 571not be barred from a patent in this country, and his right to a patent would not be affected. But where an invention has been patented in a foreign country, or has been described in a public work, then a man claiming to have been the inventor in this country is presumed, in the eye of the law, to have been acquainted with that invention as it was known in the foreign country.

It is for you to inquire whether this Ashby machine, as it is proved before you by the models, is identical with the machine of Frost & Monroe—whether it contains all the separate elements and combinations which are included in their machine. Upon that subject there is some discrepancy in the testimony. Mr. Knight and Mr. Clough are very clear and unequivocal in the expression of their opinion that they are dissimilar in all their essential characteristics; while, as I remember, Mr. Blanchard and Mr. Forbush, witnesses for the defendant, give it as their opinion that there is a substantial identity between the two machines. It is not my purpose to go into a critical analysis of these machines as they are described and claimed in the specifications, or as they are described and shown in the mills before the jury. I will observe, however, that the jury will be greatly assisted in all these inquiries by a reference to the models. Indeed, there is no kind of testimony that is more reliable in regard to the true structure and character of a machine than an accurate model. It is a witness that can not lie; the jury may rely on it, and it will be for the jury, if they find it necessary, to institute a comparison from the models of these two machines, and then decide whether they are identical. And then, as I said before, the question will be, not whether there may not be elements in the Ashby machine which belong to this machine of Frost & Monroe, but whether they find in the Ashby machine all the combinations claimed by the patent to Frost & Monroe, and embraced in the specifications of the reissued patent. It appears, by reference to the specification, that the parties who applied for this reissue were familiar with the Ashby machine, for they refer to it specially in their specification; point out what they regard as defects in that machine, and it is their professed object to remedy the defects which they hold to apply to the Ashby machine.

Then, there is another machine introduced, the Bradfield smut machine, which, it is claimed, embraces the same principles as the Frost & Monroe machine. And being older in point of invention, for it was invented, it appears, in 1839, and patented in 1840, if the jury find that machine to be identical with the one covered by the plaintiffs' patent, of course that would be fatal to the novelty of the Frost & Monroe invention. And here, I may observe, that that machine was intended and invented for an entirely different purpose from that of Frost & Monroe. But if the jury should come to the conclusion that that machine, although a smut machine, and designed originally to separate smut from wheat, embodies the same principles with the plaintiffs' machine, and that, without the exercise of invention, it could be changed so as to produce all the useful results of the Frost & Monroe machine, it would have precedence undoubtedly, in point of novelty, over the machine invented by Frost & Monroe, provided the Bradfield machine was actually perfected and brought into use. If it was merely got up for the purpose of experiment and not practically tested, it would not be regarded as a perfected invention. As has been well said by counsel, that which a person perfects, or invents and applies to a practical use, that is to be regarded as the invention, and the mere knowledge by an individual of a prior mechanical structure similar to the one patented, which has not been used practically, would not be an answer to the novelty of the later patent. I do not know that I ought to detain you with further remarks in regard to the invention of Bradfield; it has been so much discussed by counsel.

Mr. Sage: The Straub smut machine was also introduced for the defense, your honor.

THE COURT: Yes, sir; there was a patent put in evidence. I think, therefore, gentlemen, that after the thorough discussion which has been had, by the able counsel on both sides who have dissected and analyzed those inventions, and with the knowledge, too, that some of the jury, at least, have a practical acquaintance with mechanics, I think I may safely leave the question of the novelty of the Ashby, and the Bradfield, and the Straub inventions with you, and leave it to you to decide whether, upon the principles that I have indicated, any of them anticipate the invention of Frost & Monroe.

There is another matter to which it will be necessary for me to direct your attention, and that is the question of infringement. Upon that there has been very little controtroversy. It is conceded that the machine used by the defendants in this action, and which is claimed to be an infringement of the invention covered by the reissued patent, is the Ashby machine, with the addition of certain features or elements claimed to be taken from the Frost & Monroe machine and applied to that machine. It is not, I believe, controverted, that if the jury should find the patent to be a valid patent, and that it is not impeached for want of novelty, there is an infringement of it by the use of this machine. It will, however, be for the jury to say whether the machine that is before them, and used by the defendants, is substantially identical with that covered by the Frost & Monroe invention. It is incumbent on the plaintiffs, upon this issue of infringement, to make it appear affirmatively, and to the satisfaction of the jury, that their machine has been infringed. 572If the jury find the issues for the plaintiffs to which I have adverted there will then be the inquiry as to damages; but that, as I am informed, is a very immaterial inquiry. The damages in this case will only amount, as claimed by the plaintiffs, to some sixty dollars, it appearing from the testimony that the defendants have manufactured only five hundred barrels of flour by this machine. It is claimed, however, and is doubtless the fact, that collaterally this case may be of great interest and importance, not only to the plaintiffs in this action, but to other parties elsewhere. The struggle, on the part of the plaintiffs, and that on the part of the defendants undoubtedly is, not with a view to the damages to be recovered in this present action, but to have a finding by the jury as to the validity of this patent.

The jury found a verdict for the defendants.

[For another case involving this patent, see note to Carr v. Rice, Case No. 2,440.]

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., reprinted in 2 Bond, 115, and here republished by permission. Merw. Pat. Inv. 426, contains only a partial report.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.