Case No. 13,509.

23FED.CAS.—13

STOVER et al. v. HALSTED et al.

[13 Blatchf. 95; 2 Ban. & A. 98;2 8 O. G. 558.]

Circuit Court, S. D. New York.

Aug. 3, 1875.

PATENTS—NOVELTY—IMPOSSIBILITY—CONSTRUCTION OF CLAIM—PLANING MACHINES.

1. The 3d claim of letters patent granted to Henry D. Stover, July 23d, 1861, for an “improvement in planing-machines,” namely, “the arrangement of matching cutters, to be adjusted both laterally with each other, and vertically upon the bed-piece, essentially as described, in combination with the platen, so that the planing and matching of the piece may both proceed at the same time, or either the planing or matching may be done separately, whether the platen be made movable with the piece secured thereupon, or the platen be fixed, and the piece be made to move thereon,” is a valid claim.

2. Although lumber cannot be matched upon a movable platen by the machine, because the matching spindles project through apertures in the platen, and would, when in a position for matching, prevent a forward movement of the platen, yet, as the description of the machine in the specification shows that no such mechanical impossibility was contemplated, the claim must be so construed as not to involve such impossibility.

3. The question of the infringement of said 3d claim, considered.

4. Said 3d claim is infringed by the devices described in letters patent granted to Rufus N. Meriam, November 5th, 1867, for “improvements in planing machines.”

5. Said 3d claim is not void for want of novelty.

[This was a bill in equity by Henry D. Stover and J. A. Fay & Co., against Ezekiel S. Halsted and Gilbert W. Merritt, for an injunction to restrain the infringement of letters patent No. 32,904, granted to H. D. Stover July 23, 1861.]

Samuel A. Duncan and George Gifford, for plaintiffs.

Abbett & Fuller, for defendants.

191SHIPMAN, District Judge. This is a bill in equity, praying for an injunction and an account, and is founded upon letters patent for an “improvement in planing machines,” which patent was issued to Henry D. Stover, one of the complainants, on July 23d, 1861. The other complainants, J. A. Fay & Co., are a corporation, and the assignees and owners of an undivided half interest in so much of the patent and of the invention covered thereby as is embodied in the third claim of said patent The assignment was executed September 14th, 1868. The answer admits that said patent was issued to said Stover, and puts the complainants to proof of their present title thereto, and alleges that the patent is void for want of novelty. The defendants deny that they have infringed, by averring that the only machines which they use, or have used, for planing or matching lumber, are machines made under letters patent which were granted to Rufus N. Meriam on November 5th, 1867, and which patent is alleged to have been for a “different invention from that claimed by said Stover in his patent.” The answer also avers that the complainants are equitably estopped, by their own acts, from any recovery in this suit. The fact that J. A. Fay & Co. are a corporation, is, in effect, admitted by the pleadings.

The machine to which the alleged improvements in each of the patents relate, is a machine for planing and matching lumber. Machines for planing the surface of boards, and at the same time for planing or grooving and matching the edges of boards, have been long in use, and were well known prior to the date of the Stover patent. In these machines, the boards were planed by means of a cylinder, which occupied a horizontal and transverse position above the bed or platen upon which the boards were placed, and the edges of the boards were, at the same time, grooved and matched by means of matching cutters. These cutters were attached to spindles which were supported in a vertical position, so as to project through and above the bed, and thus enable the, knives to operate upon the edges of the lumber as it passed between the knives after leaving the planing cylinder. The machines were also provided with mechanism, by means of which the space between the matching cutters could be increased laterally, so that stuff of different widths could be matched upon the same machine. Although, in the machines which were in use prior to the Stover patent, there were devices which caused a slight vertical adjustment of the matching cutters upon their spindles, so that lumber of different thicknesses could matched, yet there was no machine in which the matching apparatus could be entirely removed, by mechanical means, below the surface of the platen, when the surfacing of wide boards only was desired. Oftentimes there was a necessity for planing without matching, boards of greater width than would pass between the matcher heads, and, in such case, it was necessary to detach and to remove, by hand, the spindles from the machine. It was thus impossible to surface wide boards upon a machine of ordinary dimensions, without incurring the labor and delay which were incident to a removal of the matching mechanism by hand. One object of the machines of Stover and of Meriam was to obviate the difficulty, and each patentee adopted the same general mode of accomplishing the desired result. The matching spindles are so attached to each machine that they can, at the pleasure of the operator, be simultaneously dropped below the surface of the platen. In the Stover machine, the platen is movable or stationary. When boards are to be both planed and matched, the platen is stationary, and the lumber is passed under the cutting cylinder, by feed rolls, to be planed, and thence between the matching cutters, to be matched. When boards are to be planed without being matched, they can be placed and secured upon a movable platen, which, with the lumber upon it, is passed under the cutting cylinder. But the platen cannot be moved without previously removing the matching spindles, which would, if not removed, prevent the progress of the platen. The objects of the Meriam machine are described by the patentee, in his specification, as follows: “In that variety of planing machines designed not only for planing the surface of lumber but also for matching the edges thereof, much inconvenience has resulted from the necessity of lowering that portion of the bed of the machine which supports the upper ends of the vertical shafts which carry the matching cutters, whenever it is required to adjust the said cutters for matching lumber of different thicknesses, or to move the said shaft out of the way in using the planes for surface planing only. The object of this invention is to remedy this defect.” One result which was intended to be accomplished by each machine, was the lowering of the shafts beneath the surface of the bed, when it was desired to use the machine for surfacing and not matching.

The defendants place their defence upon three grounds: (1st) That the third claim of the Stover patent, which claim alone the defendants are charged with infringing, describes a mechanical impossibility and a machine destitute of utility; (2d) that the Stover patent is void for want of novelty; (3d) that the Meriam machine is not an infringement of the Stover patent.

(1) Is the 3d claim of the plaintiffs' patent valid? The claim is as follows: “I also claim the arrangement of matching cutters, to be adjusted both laterally with each other and vertically upon the bed piece, essentially as described, in combination with the platen, so that the planing and matching of the piece may both proceed at the same time, or 192either the planing or matching may he done separately, whether the platen be made movable with the piece secured thereupon, or the platen be fixed and the piece be made to move thereon.” The defendants contend that the patentee is confined, by this language, to a mechanism whereby the lumber may be both planed and matched at the same time, or planing and matching may be done separately, either upon a movable or a fixed platen. It is obvious, that the lumber cannot be matched upon a movable platen by the Stover machine, because the matching spindles project through apertures in the platen, and the spindles, when in a position for matching, would prevent a forward movement of the platen; and it is also obvious, from the description of the machine, that no such mechanical impossibility was contemplated.

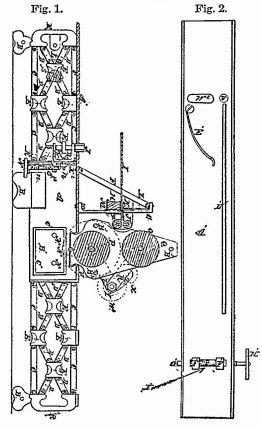

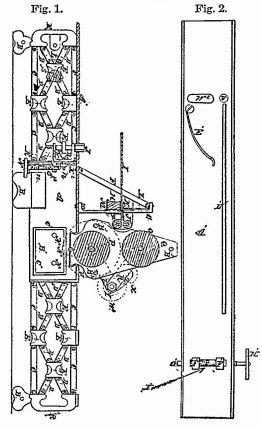

[Drawing of Patent No. 32,904, granted July 23, 1861, to H. D. Stover, published from the records of the United States patent office.]

The specification is as follows: “To the platen A' is secured a guide D', which may be removed at pleasure; this correctly guides the board, in connection with the spring E', to be matched by cutters, which may be raised up through holes V2 and W2, formed through the platen for that purpose, and adjusted at the desired elevation, they being driven by pulley 8 from pulley Q', on a drive shaft L'. The platen may thus be used stationary, and over which the boards may be moved by feed rolls, to be both planed and matched on both edges at the same time, or either may in the same manner be done separately, or the platen may be moved by any means (not necessary to be shown), and the lumber secured thereupon, while lying perfectly natural, by jaws F', operated by right and left hand screws G', to pinch and hold the piece, by turning the lever H'. * * * In order to dress dimension lumber, the platen is moved in bed along with the piece secured upon it to be dressed; and, when boards are to be dressed by passing them under the cutting cylinder, requires that a set of feed rolls shall be combined with the other portions of my machine, to feed the boards or pieces over the platen A' and under the cutter, to be dressed, the platen being fixed during such operation.” The intention of the patentee was to state in the third claim the improvements which he had described, and which consisted in part of devices for the removal by mechanical means of the matching apparatus when “dimension” lumber was to be dressed, that is planed and not matched. The third claim is not expressed with accuracy, but should be construed “ut res magis valeat quam pereat,” and in connection with the specification, so that “the inventor shall have the benefit of what he has actually invented.” Woodman v. Stimpson [Case No. 17,979]. “If the court can clearly see what is the nature and extent of the claim, by a reasonable use of the means of interpretation of the language used, then the plaintiff is entitled to the benefit of it, however imperfectly and inartificially he may have expressed himself.” Ames v. Howard [Id. 326]. The inventor intended to claim a surfacing and matching machine, in which the matching cutters were adjusted laterally and vertically, in combination with the platen, and were so adjusted vertically that the matching mechanism could be mechanically dropped below the platen, when surfacing alone was to be done. By such a machine the matching and planing could be done at the same time, or the planing could be done separately with the matcher cutters removed, or the matching could be done separately when the cutters were raised above the surface of the platen. He had previously claimed the movable platen, which he supposed to be an improvement upon other planing machines. The movable or fixed character of the platen is not a necessary part of the improvement to which the third claim relates, and might have been omitted from the statement of that claim. A construction which should compel the patentee to the declaration that his machine could either match or plane boards when placed upon a movable platen, the matching cutter being upon stationary arbors projecting through the platen, would be a construction of the utmost rigor, and in violation of the liberal rules in regard to the interpretation of patents, which have 193prevailed in courts of this country. It is a just and reasonable construction to hold, that the concluding clauses of the claim were introduced parenthetically, and related to the platen which the patentee had previously claimed, and had no reference to the planing or matching which are mentioned in the clauses which immediately precede those now under discussion. Thus construed, the claim would read as follows: “I also claim the arrangement of matching cutters, to be adjusted both laterally with each other, and vertically upon the bed piece, essentially as described, in combination with the platen, (whether, the platen be made movable with the piece secured thereupon, or the platen be fixed and the piece be made to move thereon,) so that the planing and matching of the piece may both proceed at the same time, or either the planing or matching may be done separately.”

(2) Does the Meriam machine infringe the complainants' patent? The object of the Meriam machine has already been given in the language of the patentee. One object was to “move the shaft out of the way, in using the planer for surface planing only.” He also states, that, “by this arrangement, they” (i. e., the vertical spindles) “can be lowered beneath the surface of the bed, for surface planing only, without removing any portion of the bed, and in a moment of time.” In the Stover patent, the device by which the matching cutters are dropped below the surface of the platen is thus described: “The matching cutters and bar X2 are made vertically movable and adjustable by sliding in grooves n, which are formed in central portion of bed piece A, by means of screw O1, threaded and fitted to stand P1 on bar X2 and turned by wheel N1.” By this single screw the two spindles are simultaneously moved above and below the surface of the platen. The same simultaneous movement is effected by double racks instead of by a single screw, as in the model which was used upon the trial. The same movement is effected in the Meriam machine by racks, pinions and a weighted lever. The mechanism is thus described by one of the defendants' witnesses: “This is accomplished by two separate sliding steps, having their motion vertically, each step provided with a rack in which mesh two pinions connected together by a longitudinal shaft By rotating this shaft, it gives to the sliding steps which carry the matcher spindles a vertical motion sufficient to raise them to their places when performing their work, or depress them entirely out of the way.” The elevation and depression of the matcher spindles in the two machines is performed by substantially the same means, and in substantially the same way. It is true, that the Meriam machine is probably an improvement upon the Stover machine, but the principle and essential elements of the two machines are the same.

It is claimed that the Meriam machine does not infringe the plaintiffs' patent, because the specifications of the Stover patent describe no method by which a lateral movement of the matcher spindles can be produced. A lateral movement of the matching mechanism was well known prior to the date of the Stover patent, which was not granted for any improved lateral adjustment. The third claim was for the arrangement of matching cutters, to be adjusted both laterally and vertically, as described, in combination with the platen. The method of vertical adjustment is described and claimed. Any appropriate and customary method of lateral adjustment could be used, and one method was indicated in the drawings, but, as the patentee claimed no improvement in the mechanism by which lateral motion was obtained, it was not important to give a description of any particular method of accomplishing this result, when the methods already in use were well understood.

The third claim of the Stover patent is for “an arrangement of matching cutters.” In the Meriam machine the cutting blades are placed upon “heads” of larger diameter than that of the spindles to which the heads are attached, the heads are removed from the spindles by hand, and the spindles are then dropped below the surface of the platen. In the machine which was shown in the Stover patent the cutting blades are inserted in slots in the end of the spindles, and are raised and depressed with the spindles. It is contended that the Stover patent is limited to an arrangement of cutters or knives which must be lowered by mechanical means, and that the patent is not infringed, by reason of the fact that, in the Meriam machine, the matching spindles only are carried below the platen. The object of the Stover invention was to enable wide surfacing to be done upon a planing and matching machine of ordinary width. To accomplish this object the entire matching apparatus must be removed below the surface of the platen. In the Stover machine, as shown in the drawings, the spindles and cutters are simultaneously dropped. The cutters cannot be lowered unless the spindles are lowered also, and, unless the spindles are lowered, the machine cannot plane wide boards. The invention was for an arrangement of the cutting mechanism, and it would have been a more accurate use of language, had the word “mechanism,” or an equivalent term, been used, instead of the word “cutters;” but, by a common form of expression in the language which was employed, a part of the mechanism was substituted for the whole.

But, in case a limited signification is given to the word “cutters,” the conclusion for which the defendants contend is not reached. The cutters or knives must be placed upon spindles, and the “arrangement of matching cutters” is an arrangement upon spindles which are so vertically adjusted that the 194whole can tie dropped below the surface of the platen. The matching spindles of the Meriam machine are so vertically adjusted that they can be lowered below the surface of the bed, and, in the mechanism by which the dropping of the spindles is effected, the Stover patent is infringed. The Meriam machine “incorporates in its structure and operation the substance” of Stover's invention. Carter v. Baker [Case No. 2,472].

(3) The novelty of the Stover machine. It has already been remarked, that machines which were in use prior to the Stover patent contained devices for a slight vertical adjustment of the matcher cutters, so that boards of different thicknesses could be accurately matched. This vertical adjustment was sometimes effected by a thread at the upper end of the spindles, and sometimes by loosening a set screw which secured the cutter head to the spindle. These machines did not contain any device by which the spindles could be simultaneously dropped below the surface of the platen at the will of the operator, so that boards could be planed which were wide enough to pass over the top of the spindles thus lowered. Upon the entire proofs it does not appear that any machine existed prior to the date of the Stover patent, which had the principle of the Stover machine.

(4) As to equitable estoppel. The testimony in regard to Stover's propositions to a witness, and one of the manufacturers of the Meriam machine, is, if true, not sufficient to justify a court in dismissing the bill.

Let a decree be passed for an injunction and an account.

2 [Reported by Hon. Samuel Blatchford, District Judge, and by Hubert A. Banning, Esq., and Henry Arden, Esq., and here republished by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.