Case No. 13,453.

23FED.CAS.—7

STILWELL & BIERCE MANUF'G CO. v. CINCINNATI GASLIGHT & COKE CO. et al.

[1 Ban. & A. 610; 7 O. G. 829; Merw. Pat. Inv. 455.]1

Circuit Court, S. D. Ohio.

Jan., 1875.

PATENTS—NOVELTY—INVENTION—MAKING MODEL—BOILER FILTER.

1. The first claim in reissued patent for feed-water heater and filter, granted to E. R. Stilwell, August 24, 1869, which is for “filtering material F. between a series of shelves and outlet r, substantially as described,” held valid, notwithstanding the fact that filters had been used for freeing the feed water for boilers, from the matter held in mechanical suspension therein, and the further fact, that heaters, composed of a series of shelves, had been used, for a similar purpose, to remove from the water the matter held in solution, and a portion of that held in suspension.

2. Although the operation of neither the shelves nor the filter is affected by the union of the two, in the same machine, a new result is produced, inasmuch as the water is passed into the boiler in a condition different from that which would have been produced by either of the devices separately.

3. The Stilwell patent is not invalidated by the earlier English patent of Wagner, since it is doubtful whether Wagner's device could be practically used with success.

4. There is no force in the objection, that the Stilwell patent does not specify what filtering material is to he used. The patent permits the use of any suitable filtering material, and persons skilled in the art could at once use the invention without experiment or additional invention.

5. The mere making of a model by a party, held not to constitute invention, as against a patent subsequently granted to another for the same thing.

In equity.

Wood & Boyd, for complainants.

Fisher & Duncan and John E. Hatch, for defendants.

SWING, District Judge. This suit is brought for the infringement of letters patent, granted to E. R. Stilwell, for improvements in feed-water heaters and filters, and vested, by assignment, in the complainants. Three patents are claimed to have been infringed. The first, reissue No. 2,160, dated January 23, 1866; the second, reissue No. 3,618, dated August 24, 1869;2 the third, letters patent No. 93,244, dated August 3, 1869.

The respondents file separate and joint answers, denying infringement, and that E. R. Stilwell was the original inventor, and setting up prior invention by James Armstrong, and prior use by sundry persons, named in said answers. The invention described in the first patent, relates to the means of supplying water to a “feed-water heater and filter,” and of effecting the separation of foreign elements therefrom; the first claim of which is as follows: “The overflow box C, the pipe b, arranged with reference to the vessel A, substantially as described, and for the purposes specified.” And this is the claim alleged to have been infringed by the respondents.

[Drawing of reissued patent No. 2,160, granted January 23, 1866, to E. R. Stilwell. Published from the records United States patent office.

By reference to the specification and drawings of the patent, it will be seen that the end of the induction pipe b, through which the water flows, is so placed in the overflow box C as to be completely immersed, whereby the steam is prevented from entering the pipe. It is not claimed that the respondents have, in fact, any such overflow box as complainants, in form; but it is contended, that the upper plate of the respondents' heater is so constructed, and the end of the induction pipe so arranged, as that the end, in fact, is immersed, thus accomplishing the same result by equivalent means. Upon this point, there is a difference in the testimony of the witnesses for the complainants and respondents; but the model No. 4, in evidence, stipulated by complainants as correctly representing the machine of the respondents, shows, very clearly, that by its relations to the upper plate of the respondents' machine, it cannot be immersed; the space between the discharge orifice of the pipe, and upturned sides of the plate, is so great, that by no possibility 96could the water rise, before overflowing the plate, so as to immerse in any degree the pipe. It is suggested by counsel, that the relations of the pipe to the plate, may have been changed after the witnesses examined the machine. As to that we cannot speak; but it is stipulated that the model correctly represents the machine, and it shows no such relations, as claimed. The first patent is not, therefore, infringed by the respondents.

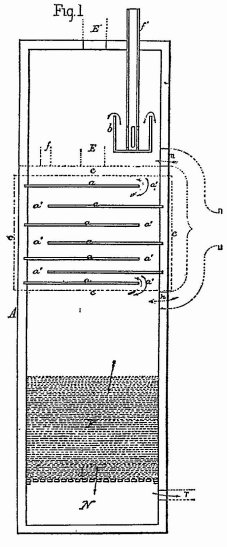

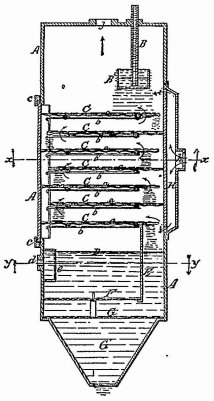

Drawings of reissued patent No. 3,618, granted August 24, 1869, to E. R. Stilwell. Published from the records of the United States patent office.]

The invention of the second patent is set forth in its claims as follows: “1. Filtering material F, between a series of shelves, and an outlet r, substantially as described. 2. The arrangement of steam inlet n, shelves a, a, filtering material F, and outlet r, in a vessel A, substantially as described. 3. Depositing plates a, a, a, constructed and arranged substantially as described. 4. The arrangement of steam pipes m, and n, with reference to the plates a, a, a, substantially as specified. 5. The combination of the vessel A, the plates a, a, a, the plate d, the steam pipes m, n, and E, and waterpipes f1, and r, substantially as described.” Complainants allege that the first and second claims of this patent are infringed.

The first claim is for the arrangement of three elements—filtering material, a series of shelves, and an outlet—and this arrangement is of that character, that the filtering material may occupy such position between the series of shelves and the outlet, as that the water, after flowing over the several plates, will pass through the filtering material on its way to the outlet.

The second is for the arrangement of steam inlet, shelves, filtering material and outlet. All of the elements embraced in these claims are old, and have in some way been in use, and connected with devices for heating, purifying, and separating water for steam boilers. The filtering material is found in the Covington, Greenfield, Brownell and Seaward devices; the series of shelves in the Wagner, Hooton, and Burden devices; and the outlet and inlet in all the devices referred to. This is not, therefore, in either of the claims, a combination or arrangement of any new element, or new elements with old elements, neither is it a combination of old elements applied to a new purpose; but it is bringing together, and combining and arranging in a single machine or device, that which existed before in several, and each performing the same office in their new relations which they did in their old. In the new, the water passes over the shelves in a thin sheet, is subject to the action of steam passing through the spaces between the shelves, and in this way, and by these means, the crystallizable atoms in the water will be deposited upon the shelves, and the water will be considerably heated. In the old, the water spreads in very thin films, during its whole course, on the heated partitions (shelves), and is kept constantly boiling. From this it results that all matters settling, whatever may be their nature, held in suspension or solution, are not only divided, but a portion of them are brought to adhere and incrust on the partitions (shelves), where they gradually deposit, according to their density. The filtering matters, 97in the new, is to deprive the water of its less soluble particles of matter, and, in the old, to free it from any sand, mud, or other foreign matters which may be mechanically intermixed therewith; and when brought together, as in complainants' device, it is difficult to see in what way the former or customary action of either is modified by its connection with the other. It is not claimed that the relation of the filtering matter with the shelves, causes them to perform any new office, or even to perform their customary office in any better or more effective manner—no increased crystallization, adhesion or incrustation. Neither can it be successfully shown, that the filtering material, by its relation with the shelves, performs any new office; it is for freeing the water from matter mechanically intermixed with the water—mechanically held in suspension—and it is by no means clear, from the evidence, that its relation enables it to perform this office in a more effective manner.

If, then, the operation of neither is affected by the other, does their union, their action in the same device, produce a result not produced by some of them separately? By the series of the shelves, the matter held in solution was crystallized, and adhered and incrusted to the plates, and a portion of that held in suspension was also deposited upon them; but a large portion of the matter held in suspension, still remained in the water, and, from the lack of the filtering material, passed into the boilers. By the filtering material a large portion of the matter, held in mechanical suspension, was taken up raid separated from the water; but, from the lack of the series of shelves, the matter held in solution was not separated from the water, but passed into the boiler; but by combining both in a single machine, both of these objects are accomplished, and the water is passed into the boiler, in a condition, different, from that in which it was, in passing from either of the devices after their separate action upon it. If this be so, a new result is produced by the union—a result not previously produced by either of the elements acting separately—which removes it from the doctrine of aggregation, as laid down in the cases of Hailes v. Tan Wormer [20 Wall. (87 U. S.) 353]; Birdsall v. McDonald [Case No. 1,434].

Treating the invention, then, as a combination producing a new result, is it novel? It is not contended that any of the devices, relied upon by respondents as anticipating complainants' patent, embraces all the elements, excepting that patented to Wagner. This, the respondents say, is a complete anticipation of the invention; and their expert witness, who seems to be a very intelligent man, says: “I find the invention claimed in said English patent (Wagner's), when compared with the inventions claimed in the complainants' patents, Nos. 2 and 3, to be identical in principle and operation.” And the expert witness Millward says: “I am of the opinion, clearly, that the said English patent (Wagner's) cannot be justly said to embrace or contain the invention, set forth in the first claim of the letters patent No. 2, for the reason that it does not embody filtering material between a ‘series of heating shelves and its outlet,’ the filtering material being located in the outlet pipe itself; that its capacity is insufficient to perform the functions of Stilwell's filtering material, and that it is not designed to perform them.” In speaking of the third and fourth claims of the third patent, he says: “There is, in the Wagner patent, no upward filter at all, and no mud well, from which mud can be drawn off while the heater is in operation.” Again: “I do not find in this English patent a mud well below a series of shelves, and below an upward filtering chamber; and, as I regard the construction and arrangement, as essential to the invention, specified in the fourth claim of said patent, and as it is so set forth in that claim, I am of the opinion, that the English patent of Wagner does not contain or describe the invention specified in said fourth claim.” Thus we have two men, well versed in mechanical and chemical science, presenting to the court, under oath, statements diametrically opposed to each other in regard to the principle and operation of the two devices.

Strictly construed, it is very certain that the Wagner patent does not anticipate complainants' invention, as described in the first and second claims of the second patent. Construed broadly, however, it may not be so clear that it does not anticipate it. It has the series of shelves, operating substantially in the same way, for the accomplishing of the same purpose; it has filtering material between the series of shelves and the outlet, and there is what may be called a mud well; but it seems clear, from the testimony, that, from the incapacity of the filtering chamber, and the kind of the filtering material described in the patent, the Wagner device would not accomplish the results as efficiently as complainants'.

The superior utility of complainants' device, over that, of Wagner, is clearly shown by the evidence in the ease, and is sufficient, in the opinion of the court, as against the Wagner device, to establish its novelty; for it is doubtful whether Wagner's could be practically, successfully used. Our better opinion, therefore, is that the patent, either strictly or broadly construed, is not anticipated by the Wagner patent. It is said, however, that as no kind of filtering material is mentioned, and no function is mentioned except filtering, if it appears, that some kinds of filtering material will not work, the patent is void. By the act of congress, an inventor is to describe his invention, and the manner and process of making, constructing, and using the same, in such full, clear and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art, to make, construct and use the same. 98This specification or description, is addressed to persons acquainted with the character and nature of the business to which the invention relates, and it is only necessary that it should be so definite, or full, as to enable persons of competent skill and knowledge to construct, produce, or use the thing described, without invention or addition of their own, and without repeated experiments. The description in the patent is not, any and all filtering material, but is, any suitable filtering material. Suitable for what? For performing the function or office assigned to it, to wit, the separation of the solid matter from the hot water. This could hardly be said to embrace filtering material which would not perform the office or function assigned to it. The persons acquainted with the business, in which this invention was to be used, were familiar with the various kinds of filtering material suitable for this purpose, and would, at once, use it and put it into operation, without invention, addition or experiment. The patent is not, therefore, for that reason, void.

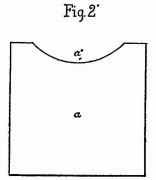

[Drawing of patent No. 93,244, granted August 3, 1869, to E. R. Stilwell. Published from the records of the United States patent office.]

Passing from the second to the third patent, the third and fourth claims of which it is alleged respondents infringe—the third claim of the patent is: “The filtering chamber D, constructed and arranged substantially as described.” Without entering into an extended review of the evidence upon this claim, but examining it in connection with the specification and drawings, and with the other claims, and in the light of the state of the art at the time of the invention, I do not think it can receive that broad construction necessary to embrace the filtering-chamber of the respondents, and, receiving a strict construction, respondents do not infringe this claim.

The fourth claim is: “The mud well G1, arranged below a filtering chamber D, in combination with the shelves and steam inlets, substantially as described.” A broad construction of this claim would embrace the defendants' mud well. But can this claim, from the state of the art, and fair interpretation, receive such construction?

Mr. Millward says: “Mud wells, as employed in steam boilers and other apparatus, have long been known as appliances for the collection and discharge of mud, and not simply for the collection only.” Mr. Stilwell was familiar with the state of the art, at the time he prepared his specifications, and from the specification, it is very clear that he had no idea that he was claiming as his invention anything but the particular mud well, which he described in his specifications and drawings. The claim is the mud well G1, and the mud well G1 is described in the specifications and drawings, as below the strainer G, and as of funnel shape and form. Could complainant have entertained the idea, that he could remove the entire mud-well, shown in his drawings, and described in his specifications, below the strainer G, and substitute in the place of the strainer G, a plate at the terminus of shell A, and claim the space between the filtering chamber D, and such plate, as the mud well of his invention, as described in his patent? I think not. Nor do I think that the specification, drawings and claim, when fairly construed together, will bear any such construction; but his invention was the mud well, which he so particularly and minutely described, and as such, is not embraced in the defendants' device.

The only remaining question in the case is, whether the subject of the first and second claims of the second patent, is the invention of E. R. Stilwell, or of the defendant, James Armstrong?

The defendants claim, that the device, as used by them, was the invention of James Armstrong; that it was invented by him, and put into public practical use, in the latter part of the year 1845 or 1846; and, have introduced in evidence, a model which they claim represents the device which was so constructed, and so used, and which was made, they say, by James Armstrong, in 1857, a period before complainant claims to have invented his device. As bearing upon the date of the existence of the model, and the construction of the device, and its public use, the depositions of eighteen witnesses were taken by the parties, twelve by the respondents, and six by the complainants. Of the respondents' witnesses, six testify in relation to the model, 99and eight in relation to the device. The six witnesses of the complainant were all examined in relation to the alleged construction and use of the device.

As to the model: James Armstrong testifies, that he made it in 1857, and that it represented the machine he made and used in 1845 and 1846. William Armstrong testifies, that he saw the model in 1857. Ruby E. Lucas testifies, that she saw the model in 1860, under peculiar circumstances, and placed upon it the initials of herself and friend, which she finds upon it now. John G. Sherwood testifies, that he saw it in the spring of 1862. Olin Armstrong testifies, that he saw the model in 1861 or 1862. Irwin E. Harris, that he saw it in 1863. This testimony would seem to establish the existence of the model at a period as early as 1857.

The testimony offered by the respondents, to establish the existence and public use of the device, is as follows: James Armstrong testifies to the construction and use of the device in the latter part of 1845, or fore part of 1846. William H. Armstrong testifies to the use of the device, about the same time; he also gives a general description of it. Robert A. Gettings testifies, that he helped make the device; that he furnished the plank; and gives a general description of it, but does not remember all its parts, and also testifies to the use of it. George A. Mead, testifies to the use of a long box, from five to eight feet long, with an upright at one end; saw Armstrong repairing it, with a pipe at one end. William Cuykendall testifies, that he went to look at Armstrong's mill, and saw there a wooden heater in a rough state. This was before he put steam in his mill, which was in 1847. F. W. Owings testifies, that he drew a load of straw to the mill, which was put into a box, which was used for filtering or clearing water. The box was square one way, and long the other, with a spout on one end of it, resembling the model of 1857. David Trucell testifies, that he heard William Armstrong speak of the heater that he was going to have put in the mill; didn't say whether it was wooden or no; but didn't know that it ever was put in. James S. McCarrell testifies, that, in 1867, William Armstrong told him his brother had a similar machine in successful operation, several years before that, at his saw mill, made of wood; heated the water, and removed the mud before it went into the boiler. Stephen E. Harris testifies, that he saw the model in 1869, and James Armstrong then told him, that it represented a heater and filterer he had made many years before that, in a steam mill in Huron county; that it was of wood, and worked well in practice.

The testimony offered by the complainants to disprove the existence and public use, of the device, as claimed by the respondents is, first, the deposition of John Collins, who testifies that he assisted in putting up the works, setting the engine, and fixing the machinery for starting the grist mill; that the heater used there was of sheet-copper, and used for five months, up to the time he left, and there was nothing of the kind described by Armstrong used while he was there. Seymour N. Sage, who testifies that he commenced working for Armstrong, Long & Gettings, in the New Haven Mills, in the fall of 1845, and worked there till the 1st day of December, 1846; that he helped get out the timber, and put up the saw-mill frame, late in the winter, or early in the spring, of 1846, and helped put in a steam engine, a tub-shaped iron heater, used from the time it was put up until he left in December; that they never used the device described by Armstrong in that or any mill. John and William Armstrong were the owners while he was there. Corydon Curtiss testifies, that he was frequently at the mill, from 1846 to 1847; saw Seymour Sage there, saw cast-iron heater, but did not see wooden one; thinks if one had been used, would have seen it; cast-iron heater used as long as he recollected the mill, and don't recollect of ever seeing any other heater used in the mill. Russell Curtiss testifies that he lived near the mill from 1845 to 1847; was acquainted with Seymour N. Sage, who sometimes ran the engine, and sawed in steam mill about eight months; taught Sage how to run the saw mill; recollects something they called a heater; thinks it was made of iron; it was removed he thinks, in March, 1847, and thinks he put the heater in the wagon, and thinks he would have seen the wooden heater if it had been there. David Turcell testifies, that he worked in Armstrong's mill in January, 1846; that he worked there about eight weeks; an iron heater was used while he was there; no other was used; don't think Seymour N. Sage worked there while he was there; quit before he came; heard Armstrong speak of getting another heater; didn't say whether it was to be a wooden one or not, and don't know whether he ever put it in. Asher Taylor testifies, that he owned an interest in the mill during the time that Finch owned an interest in it. “I bought after he did, and sold before he did.” Thinks he purchased in May, 1846, and sold last of August or in the fall, but not certain whether 1846 or 1845; an iron heater used while he was there, and no other that he remembers while he owned the mill; if there had been a wooden one, would likely have recollected it George W. Benard testifies, that he is a machinist, lived within three-fourths of a mile of the mill; worked in it while it was owned by William Armstrong and Finch, and when Mr. Sage was there; began the latter part of April or May, and worked till July; about a year after, worked for Taylor; tore out fore-bay and engine timbers; supposed the heater made of cast iron; no other in use while he was there; if wooden heater had been there, he thinks he would have known it.

Having thus shown what the evidence upon these points is, does it establish the fact, that the patentee was not the first and original inventor? 100The presumption of the law is, that he was the first and original inventor, and it casts upon the respondents, who deny it, to show by clear and satisfactory proof, that he was not. The evidence, in regard to the existence of the wooden heater at the Armstrong mills, is very conflicting. On the one hand, the witnesses state it was there and used; on the other hand, they say that no such heater was there. Two of the witnesses for the respondents say they made the device; yet, on the other hand, witnesses, who are not impeached, say they worked there, during the time that it is claimed to have been made, and the time when it is said to have been used, and no such heater was there; and others say they saw it there; and yet others, who were frequently there, and familiar with the premises, say they never saw any such heater there; and if it had been there, they would have been apt to have seen it. Again, the time when it is claimed this wooden heater was used, was seventeen or eighteen years before the witnesses were testifying, and nothing is heard from it, until eleven or twelve years afterward, when it is claimed that a model of it was made; but, then, no effort is made to procure a patent for it, or to put it into use, for more than ten years after the making of the model. And it is a matter not to be forgotten, that James Armstrong, in 1868, took out a patent for a device different from that of the model of 1857, which he claims represented his invention of 1845 or 1846, and that afterward, in 1869, he took out a patent for substantially the same invention represented by said model. If the making of the model constituted invention, I should hold, that the proof established the fact, that James Armstrong was the prior inventor; but that does not constitute invention, and it can only be used as an item of testimony, reflecting upon the making and using of the wooden heater in 1845 or 1846. Taking it in connection with the testimony on that point, and weighing all the testimony together, I cannot say, that it is of that clear and satisfactory character, as requires me to find that James Armstrong invented the device, as claimed, in 1845 or 1846.

It results, therefore, from these findings, that respondents infringe the first and second claims of the second patent; but do not infringe the first and third patents, as alleged in the complainants' bill.

1 [Reported by Hubert A. Banning, Esq., and Henry Arden, Esq., and here reprinted by permission. Merw. Pat. Inv. 455, contains only a partial report.]

2 [The original letters patent No. 44,561 were granted October 4, 1864.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.