1038 the argument upon both sides has proceeded upon that hypothesis, and properly so, for it is entirely clear that the specification requires its adoption.

1038 the argument upon both sides has proceeded upon that hypothesis, and properly so, for it is entirely clear that the specification requires its adoption.Case No. 13,281.

STAINTHORP et al. v. HUMISTON.

[4 Fish. Pat. Cas. 107.]1

Circuit Court, N. D. New York.

June, 1864.

RULES OF COURT—PATENTS—CITIZENSHIP OF PATENTEE—RECORD OF NATURALIZATION—ALIENS—WORKING MODEL—IMPROVEMENT—ORIGINAL COMBINATION.

1. The sixty-ninth rule in equity does not allow the production of such proof at the hearing as was formerly allowed in the high court of chancery in England.

2. Where a record of naturalization was offered at the hearing to rebut proof that the patentee was not a citizen of the United States: Held, that such record could not be given in evidence, as a matter of right.

3. As, however, the defendant insisted upon other grounds of defense: Held, that the record of naturalization might be received upon the payment by the complainant of all costs incurred by the defendant in proving alienage.

4. If a subject of Great Britain becomes naturalized in the United States, but afterward resides in Canada, he is, while resident in Canada, entitled to take out Canadian letters patent as a subject of the Queen of Great Britain, for it is the settled doctrine of the English law that natural born subjects owe an allegience which is intrinsic and perpetual, and which can not be divested by any act of their own.

10365. Upon the question of identity of machines, or of mechanical devices, the mode of operation and the result produced are important considerations, and if they are both clearly and substantially different, when the material or substance brought under their operation is the same, the question of identity must ordinarily be determined in the negative.

6. The use of a working model for two or three hours by way of experiment, is not a reduction of an invention to practical use.

7. The improvement of one element of a combination, though meritorious, does not give the right to use or appropriate the original combination.

8. Under the term “pistons,” Stainthorp embraces not only the pistons proper which fit the lower portion of the stationary candle molds, and the inner portion of which forms the tip molds, but also the pipes or hollow rammers, serving as piston rods, to which the pistons proper are attached.

9. The novelty of Stainthorp's patent for “improvement in machines for making candles,” granted March 6, 1855, examined and sustained.

10. The candle machines described in letters patent granted to Willis Humiston, July 17, 1855, infringe the Stainthorp patent.

This was a bill in equity [by Joseph Stainthorp and Stephen Seguine against Willis Humiston], filed to restrain the defendant from infringing letters patent for “improvement in machines for making candles” [No. 12,492], granted to John Stainthorp, March 6, 1855. A motion for an injunction in the same case is reported [Case No. 13,280].

M. B. Andrus and George Gifford, for complainants.

M. P. Norton, for defendant.

HALL, District Judge. This is a suit in which the plaintiffs ask for an injunction and account, and it is founded upon a patent “for a new and useful improvement in machines for making candles,” granted to the plaintiff, Stainthorp. March 6, 1855.

The patent was granted to Stainthorp, as a citizen of the United States, and the defendant, by his answer, not only denied the alleged infringement and interposed the defenses of want of novelty and want of utility in the patented invention, but also insisted that the patent was void, because the patentee was not a citizen of the United States, but was a subject of Great Britain at the times he applied for and obtained his patent as a citizen of the United States.

To sustain this latter defense, the defendant produced evidence showing that the patentee was born in England and was of English parentage; that on July 10, 1855, he applied for, and on September 24, 1855, received, from the Canadian authorities a patent for his invention on the allegation, verified by his oath, that he was a subject of the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland and a resident of Canada.

No evidence to show that the plaintiff, Stainthorp, had been naturalized under the laws of the United States was offered until after the plaintiff's counsel had concluded his opening argument, and one of the counsel for the defendant had spoken for some time in making his argument in behalf of the defendant. The plaintiff's counsel then produced and offered in evidence a duly certified copy of the record of the naturalization of the plaintiff, Stainthorp, on October 10, 1840. The defendant's counsel insisted that this evidence could not be received at that stage of the proceedings, except upon terms of paying costs; but the counsel for the complainants insisted that he could give the record in evidence as a matter of right. The defendant, not desiring an opportunity to produce proofs in respect there to, it was agreed, after some discussion, that if the court should be of the opinion that this record was not admissible in evidence as the plaintiff's right, and without terms, at that stage of the proceeding, it should be received nevertheless, and the terms on which it should be received be prescribed by the court on the decision of the cause. Under that agreement the argument proceeded, and this preliminary question, as well as the questions involving the merits of the controversy, is now to be decided.

If the defendant, on the production of this record of naturalization, had elected to abandon his defense, he would probably have been entitled to require the payment of all his costs subsequent to the filing of his answer, as the condition upon which this record should be received. But this he did not elect to do, and the evidence must now be received upon the payment by the plaintiffs of the fees of all the witnesses whose testimony was taken for the purpose of proving the alienage of Stainthorp, and of the officer for taking such testimony, and also the further sum of $100, as the estimated expenses of the defendant (other than such fees) in procuring and taking such testimony. These terms are imposed upon the ground that such record could not be given in evidence as a matter of right, after the argument had commenced; and I am inclined to think that the 69th equity rule does not allow the production of such proof at the hearing as was formerly allowed to be done in the high court of chancery in England.

There is nothing in the defendant's proof to overthrow the proof of citizenship furnished by this record, or to show that his oath to the application for his patent in Canada, was false. His application in Canada was made some months after his patent in the United States had been issued; and the evidence in the case shows that he removed to, and carried on business in Canada, and was married there, all which is consistent with the hypothesis that he became an actual resident of Canada after his patent was granted here, and before his application for a patent in Canada was there made. If so, he was, while resident in Canada, a subject of the Queen of Great Britain and Ireland, for it is the settled doctrine of the English law that natural born subjects owe an allegiance which is intrinsic and perpetual, and which can not be divested by any act of their own. 1037 Blackstone (volume 1, pp. 370, 371) says that this natural allegiance “cannot be forfeited, canceled, or altered, by any change of time, place, or circumstance, nor by any thing but the united concurrence of the legislature;” and that “it is a principle of universal law that the natural born subject of one prince can not, by any act of his own, no, not by swearing allegiance to another, put off, or discharge his natural allegiance to the former, for this natural allegiance was intrinsic and primitive, and antecedent to the other, and can not be divested without the concurrent act of that prince to whom it was first due.”

The question of the novelty of the invention patented to Stainthorp, arising upon substantially the same proofs as have been produced in this case, was before the circuit court of the United States for the Eastern district of Pennsylvania, in the case of the present plaintiffs and one John W. Hunter, against George v. Elkinton [Case No. 13,278], and in the circuit court of the United States for the Southern district of New York, in the case of the same plaintiffs against the present defendant [Id. 13,279]. In both, the decision was in favor of the patentee, but the effect of the decree in these cases, as an estoppel, was waived by the plaintiff's counsel on the hearing of this case; and this waiver has imposed upon this court the duty and labor of a re examination of that question in the present case.

Upon the question of identity of machines, or of mechanical devices, whenever that question arises in a patent case, the mode Of operation and the result produced, are important considerations; and if the modes of operation, and the results produced, are both clearly and substantially different, when the material or substance brought under their operation is the same, the question of identity must ordinarily, at least, be determined in the negative; and this is generally true, whether the invention patented is an organized machine, or an improvement upon an existing machine; and whether the patent is for a machine or a mechanical device, new in all its parts, or merely for a combination of two or more well known existing machines or mechanical devices.

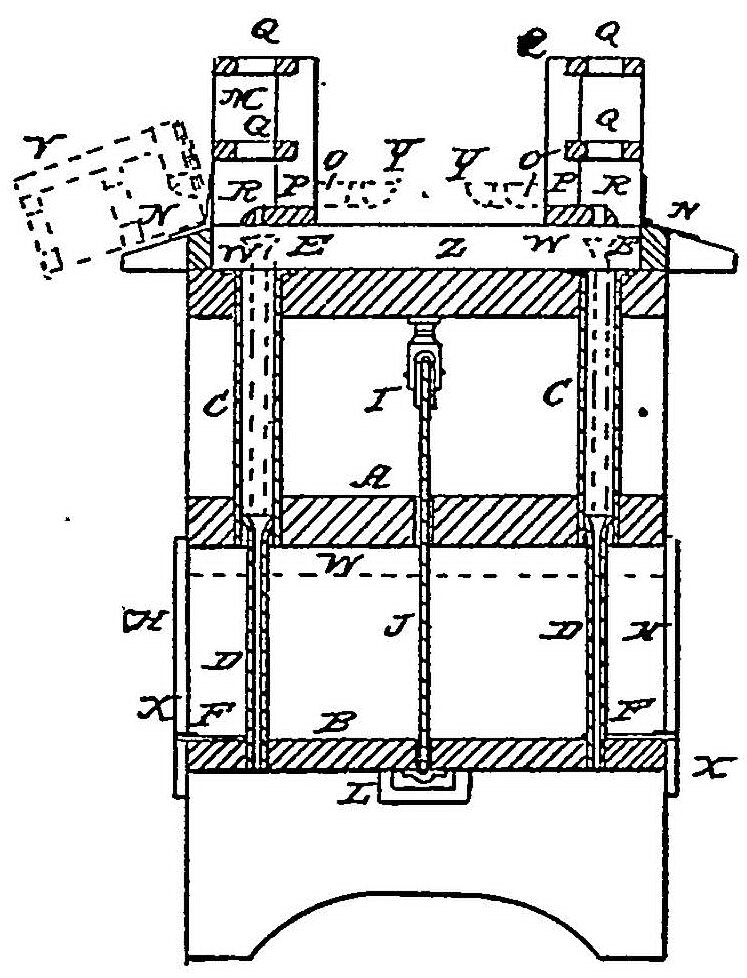

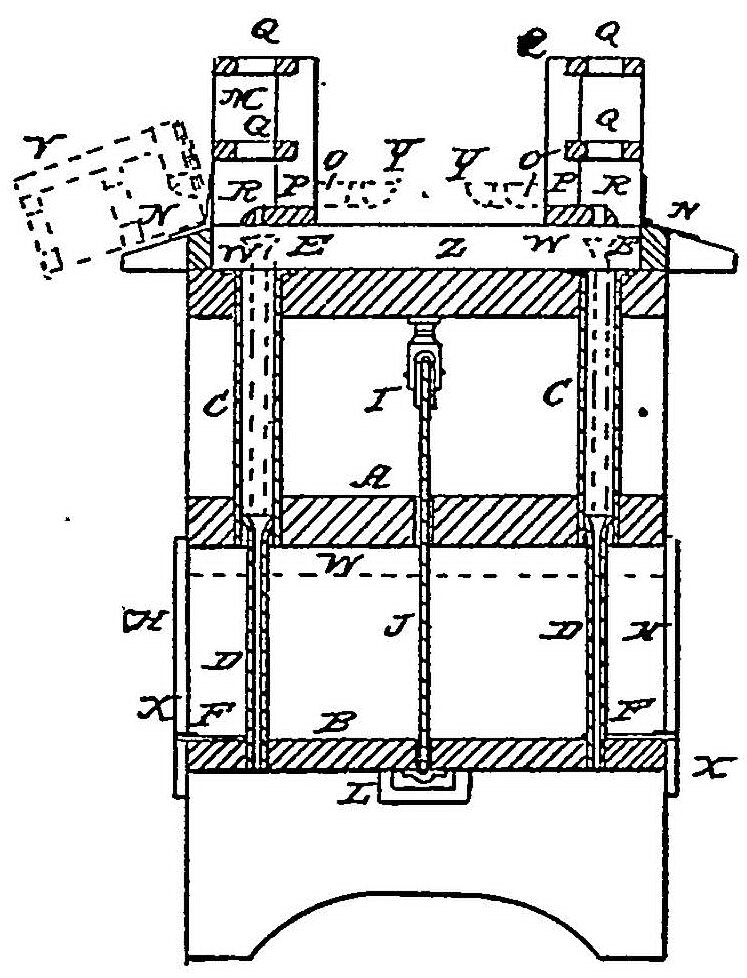

In this case the plaintiffs' alleged rights of action are based wholly upon the first claim in the Stainthorp patent; and that claim is for a combination only. It is, as has been said, a patent for an improvement in candle molding machines; and the patentee has claimed two distinct combinations. The construction of a machine for making mold candles, embodying the invention claimed, is fully described in his specifications, with reference to the annexed drawings and the letters marked there on; and this description sets forth the mode of constructing, not only the parts covered by the patent, but also portions of such machine which were before well known, and in respect to which no invention is claimed. The patentee then states the invention, or what he claims as his invention, as follows, viz.:

“Having thus fully described my invention, what I claim as new and desire to secure by letters patent, is:

“First. The employment of the pistons D, D, formed at their upper ends into molds for the tips of the candles, in combination with stationary candle molds, to throw out the candles in a vertical direction, substantially as herein set forth. I do not claim the use of clasps separately considered, but I do claim:

“Second. The combination of the rack, tipbar, and clasps, constructed and arranged substantially as described, and for the purposes specified.”

It would be difficult, if not impossible, to explain fully the state of facts upon which this question of novelty arises, without reference to exact drawings exhibiting the plaintiffs' alleged invention, and the construction of the several machines, the prior existence of which it is insisted ought to defeat the plaintiffs' action.

The question will there fore be discussed with reference to the drawings and models, given in evidence, but no detailed description of them will be attempted.

The language of the specification of Stainthorp, and the drawings annexed, clearly show, that under the term “pistons D, D,” he embraces not only the pistons proper which fit the lower portion of the stationary candle molds, and the inner portion of which forms the tip molds, but also the pipes or hollow rammers serving as piston rods to which the piston proper is attached. Indeed,

[Drawing of patent No. 12,492 granted March 6, 1855, to J. Stainthorp; published from the records of the United States patent office.]

1038 the argument upon both sides has proceeded upon that hypothesis, and properly so, for it is entirely clear that the specification requires its adoption.

1038 the argument upon both sides has proceeded upon that hypothesis, and properly so, for it is entirely clear that the specification requires its adoption.

The claim alleged to be infringed is that of the invention of the combination, or, in the language of the patentee, the employment of the combination of the pistons D, D (including the pipes or rammers, the piston rods as well as the pistons proper), formed at their upper ends into molds, for the tips of candles with stationary candle molds, to throw out the candles in a vertical direction, substantially as set forth in the specification.

The employment and operation of these pistons in combination with stationary candle molds, substantially as described in Stainthorp's specification, results in throwing the candles from the molds in a vertical direction, by mechanical force applied to raise these pistons D, D.

In the Morgan machine one element of this combination, stationary candle molds, is not found. In view of this fact, and of the additional fact that the mode of operation and construction of this very complicated and cumbrous machine are entirely different from those of the machine patented by the plaintiff, I feel no difficulty in saying that the Morgan machine is not, in respect to the combinations mentioned in the first claim of Stainthorp's patent, substantially identical with that of Stainthorp.

The Whitfield machine contains the combination of stationary candle molds with the pistons containing the tip mold, but its mode of operation is widely different from that of the Stainthorp machine. The combination of the piston and mold is not arranged or employed for throwing the candles out of the mold. The motion of the piston is so limited that its use is of little or no value beyond the effect of detaching the candles from that part of the mold to which it adheres, when cooled. This is effected by raising the candle instead of depressing it (as is done in the old hand machine by the operation termed “popping”), and the candle is drawn out of the mold by the strength of the wick instead of being forced out by the upward movement of the piston. The mode of operation of the Whitfield device is, there fore, entirely different from that of Stainthorp's. Beside, the machine of Whitfield never went into practical use. Although, a working model was made in or about the year 1849, and was soon after used for two or three hours in making candles, by way of experiment, the machine may well be considered as but an abandoned experiment. The inventor was then, and for some twelve years afterward, engaged in the manufacture and sale of the common handstand candle machine, and yet he did not manufacture or sell this machine, or procure a patent for his supposed invention; and no one, it is believed, would now use a machine of that kind whatever might be the excellence of its mechanical construction.

The Hewitt machine, so far as it affects this case, was, in its construction and mode of operation, similar to the Whitfield machine, and performed only the like operation of starting or popping the candles by the upward pressure of the tip mold for a short distance at the bottom of the mold, which forms the body of the candle. It does not appear that this machine, although described, in 1831, in the journal of the Franklin Institute, ever went into practical operation; and upon the proof in this case it can not be considered as much more than an abandoned experiment, indicating progress in the direction of Stainthorp's invention. Stainthorp's invention though first embodied in a machine of very rude and imperfect mechanical construction was early put in practice, and, although the imperfect mechanical construction of his machine was for a considerable time unfavorable to its introduction into general use, the principle of the invention was found practically useful. A better mechanical construction, a better choice in the selection of the mechanical device for raising the pistons, was desirable, and was afterward adopted; but the combination of the first claim, substantially as described in his specification, is found in his present machine and in those of the defendant.

But conceding that the devices of Hewitt and Whitfield are to be treated as completed inventions, I do not think they invalidate the Stainthorp patent. The pistons and tip molds of Stainthorp were different from the tip molds, plugs, or mandrels of the machines of Hewitt and of Whitfield, and they were not mechanically the same, for they were different in the modes of construction and operation, and performed entirely different functions. They were different in construction and mode of operation, and this different construction and mode of operation were adopted for a specific purpose for the production of a specific effect which could not have been produced by the Hewitt or the Whitfield machine. The result to be produced by the one was entirely different from that produced by the others, and was valuable; and the combination had never before been made with like elements or applied to the same purpose, and was there fore clearly patentable. Ex parte Mackay [Case No. 8,836].

Upon the question of infringement I think there can be no doubt. This question must rest upon the substantial identity of the combination and device described in the first claim of Stainthorp's patent, its mode of operation, and results. It does not depend upon the mode of clasping and holding the candles after they are ejected from the molds, or upon the particular character or construction of the mechanical powers applied to force the pistons upward through the molds.

The ground on which it was most strenuously urged that the defendant had not infringed 1039was, that the pistons and pipes in the two machines, and which are both embraced in the term pistons in the Stainthorp patent, and are described as tip molds and driving rods in the defendant's patent, are not identical, because the connection between the tip mold and pipe or piston rod in the Stainthorp machine is close and rigid, while in the defendant's machine they are loosely and more or less remotely connected by a universal joint, which allows a slight lateral or oscillating motion in the tip mold while the rod moves in a direct line, and also effects the purpose of giving a sharp blow to start or pop the candles in consequence of this joint being so constructed as to allow the drive rod to move upward a very short distance before its shoulder strikes the tip mold.

In the Stainthorp machine this sharp blow, desired for the starting process, was provided for solely by allowing about one-fourth of an inch end play to the piston rod or pipe at the point near its lower end, where it was connected with the machinery for raising it upward; and in the defendant's working machine exhibited at the hearing, there was, in addition to the end play allowed at the universal joint before referred to, an additional end play of a sixteenth to an eighth of an inch at the point at or near its lower end, where it was connected with the machine for raising the drive rod and tip mold through the candle mold.

In other words, about a quarter of an inch of end play was allowed the drive rod in both machines; in the Stainthorp machine it was all allowed at the lower connection, and in the defendant's it was about equally divided between the upper and lower connections of his drive rods.

It is apparent upon the proofs in this case, that the defendant's machine has the same combination as that patented to Stainthorp; that its mode of operation and its results are the same; and that the change introduced by the defendant by the adoption of the loose connection and universal joint referred to, if of sufficient utility to sustain a patent, is but an improvement upon the invention of Stainthorp.

If the machine be defective in its construction or operation, so that the candles when raised nearly or quite out of the molds are deflected from the line of the piston or drive rod, this joint and its loose connection may be a valuable improvement; and if no end play, or insufficient end play, be allowed at the bottom of the drive rods or pistons, the end play allowed at the joint may also be of service. But this leaves Stainthorp's original combination still existing, and this new device of the defendant was only patentable as an improvement in one of the elements of that combination, and gave the defendant no right to use Stainthorp's patented combination, without a proper license. The improvement of one element of a combination, though meritorious, does not give the right to use or appropriate the original combination. Gorham v. Mixer [Case No. 5,626].

The defendant's patents do not aid him in his defense. They do not come in conflict with the views I have taken of the case. They may be valid for useful improvements in the candle machine, and these improvements may be necessary to the construction of the best candle machines in use, but if so, these patents give the defendant no right to use the invention patented to Stainthorp.

On the question of utility, there can be no doubt. The device patented, in connection with the other parts of the machine described in the specification of Stainthorp, was and is of great utility, whether used in connection with the device for holding the candles described in Stainthorp's specification, or that used in the defendant's machine.

That the agreement made upon the settlement of the former decree against the defendant in this suit constitutes no defense, is too clear to need argument.

The plaintiffs are entitled to a permanent injunction and to a decree for an account, and I do not feel at liberty, without the plaintiff's consent, to withhold the injunction until this case can be decided on appeal.

[An appeal was taken to the supreme court, where it was heard on motion to dismiss. The motion was granted. 2 Wall. (69 U. S.) 106.]

[For another case involving this patent, see Cases Nos 13,871 and 13,872.]

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.