1026

Case No. 13,273.

In re STAFF et al.

[5 Ben. 574;1 43 How. Pr. 110.]

District Court, S. D. New York.

March 29, 1872.

AUDITING ASSIGNEE'S ACCOUNTS—EVIDENCE.

1. On the auditing of the accounts of an assignee before the register, a bill for attorney's services was offered in evidence, but without full proof as to what the services were for which the items in the bill were charged. No one objected to the bill, on behalf of the creditors: Held, that the bill was evidence of the items of alleged services and disbursements, but would amount to nothing, without evidence as to the occasion and necessity and value of the services.

2. The duty of the register was not merely to adjudicate as to the bill, on the evidence submitted to him, but to examine the account, for the purpose of ascertaining, in any way he might he able, what sum ought, in fairness, to be allowed.

1027

[In the matter of John J. Staff and John J. Staff, Jr., bankrupts.] By I. T. ‘WILLIAMS, Register:

2 [I, the undersigned register, in charge of the above entitled matter, do hereby certify that pursuant to the directions of the district judge in this matter under my certificate there in of February 13th, I proceeded to the audit of the accounts of the assignee, which were duly filed with me on the 11th day of January, 1872. Whereupon the said assignee offered himself as a witness, and was examined by Mr. Whitehead, who stated that he appeared for Mr. Malcolm. At the close of his testimony, the assignee stated that this was all the testimony he had to offer. Mr. Whitehead then called Mr. Malcolm, who being sworn, was examined by Mr. Whitehead. At the close of the testimony of Mr. Malcolm, Mr. Whitehead offered in evidence a bill of the items of the claim of Mr. Malcolm, which was filed with me by the assignee as one of the vouchers of his said account, on the 11th day of January aforesaid. But I declined to permit the paper to be read as evidence of the facts that might be there in stated. To this ruling Mr. Whitehead excepted, and desired me to certify the point to the district judge for decision.

[And I further certify, that the grounds of the said decision are as follows: I have examined the paper as a voucher, and was familiar with its contents. It is duly receipted, and its validity as a voucher, i. e., as proof that the assignee did in fact consent that Mr. Malcolm should retain out of the sum of $1,339, which he claims to have collected, the sum of $89380/1000, as and for his professional services in and about collecting the same, all this was before the court at the time the case was sent back to me with directions to “audit the account of the assignee, including the item for the amount allowed by him to Mr. Malcolm,” which I construe to mean, to take testimony concerning the services claimed to have been rendered, and determine the value there of. 3 Demo, 391. I could not think this paper per se evidence of the truth of whatever might be written there in, nor could I think that it became so upon the evidence given by Mr. Malcolm, to wit: “I performed the professional services mentioned in Exhibit A” (the paper in question). “These professional charges and disbursements were made in and about collecting this very money. * * * I am acquainted with the value of professional services in the city of New York. In my opinion, the charges were very moderate. If the fund had been larger, I should have charged a larger sum.” If such testimony would make a paper admissible as evidence of the truth of whatever might be written upon it, a witness, when called upon the stand, has only to produce a paper upon which he has written what he wishes to prove, swear that what is there in written is true, and hand it up to be read as his testimony in the case. But as the paper is before the court as one of the vouchers of the assignee, we may look into it for the purpose of ascertaining what it would prove if admitted in evidence, for this will obviate the necessity of sending the case back to the register in case the district judge should be of opinion that the register erred in refusing to receive the paper as evidence of the truth of its contents. The first item is as follows: “1869, February 9. To services in the proceedings to obtain injunction against bankrupts and against sheriff of the city and county of New York, to prevent sale of property in his hands under the execution, $100.00.” He tells us here in what matter he rendered services for which he charged the assignee $100, but he does not tell us What services they were what he did for which he charges this $100. These words, if incorporated into his testimony, would not throw the faintest light upon the matters now under inquiry. He says his services in a certain matter were worth $100, but that anyone else may say what his services were worth in that matter, he must know: what was done in it. Every other item of the bill is open to the same criticism.

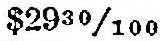

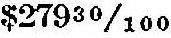

[The last item of the bill is as follows: “To five per cent. in collecting moneys from the bankrupt, $66.69.” This item is open to still broader criticism. If this item may not be proven by the paper offered, clearly the whole paper is inadmissible. But what alone would be fatal to a large part of this claim is the fact that it nowhere appears upon whose retainer the services were rendered. True, the bill is made out to “Charles H. Bailey, assignee of John J. Staff and John J. Staff, Jr.,” and no doubt Mr. Malcolm must be understood to assert and maintain that he rendered all of the services, and made all the disbursements now claimed for, for and at the request of the assignee. But he has not sworn to that, and will not probably do so, as one third of the whole amount of them were rendered and disbursed before Mr. Bailey was elected assignee. The first meeting of creditors was held, and Mr. Bailey was elected assignee, on the 3d day of November, 1869. His election was approved and he received his assignment on the 11th of the same month. The first item of this claim is $100 for services rendered on the 9th day of February previous, the very day the petition in bankruptcy was filed. If from this we infer that Mr. Malcolm was acting for petitioning creditors, the record shows that it was a case of voluntary bankruptcy. And again, if from this we infer, that he was acting for the bankrupts, his bill as well as the record shows, that Mr. Byrne was the bankrupt's solicitor, and that Mr. Malcolm was acting adversely to them; but upon whose retainer, prior to the 102811th of November, is left entirely to conjecture. But all the items of the bill of a later date are open to criticism scarcely less unpleasant. All of the services seem to have been in the bankruptcy court and in the bankruptcy proceedings, and don't seem to have been in anywise unusual in character. Assuming that everything was done by Mr. Malcolm which his bill would, in any view of it, indicate. I think, that $250 over and above disbursements is as high a sum as I have ever certified, or as this court has ever allowed for similar services in bankruptcy. The disbursements charged subsequent to the 11th of November (including a charge of  , as paid register, which, I presume, means commissioner) amount to the sum of

, as paid register, which, I presume, means commissioner) amount to the sum of  , which added to the said sum of $250 amount to the sum of

, which added to the said sum of $250 amount to the sum of  . But, on the other hand, if the district judge shall be of opinion that the rejection of the bill, as evidence of the recitals there in contained, be correct, then, clearly, there is no evidence before me upon which an audit may be founded, and it will seem to be necessary to remit the case for further proceedings.

. But, on the other hand, if the district judge shall be of opinion that the rejection of the bill, as evidence of the recitals there in contained, be correct, then, clearly, there is no evidence before me upon which an audit may be founded, and it will seem to be necessary to remit the case for further proceedings.

[I did not cross-examine either the assignee or Mr. Malcolm, and no one appeared on the part of the creditors to do so. Nor did I call other witnesses as to the value of the professional services, or as to what services were, in fact, rendered. And in view of a return of the case for further proceedings, by way of auditing the account, I crave the judgment of the court as to the duty of a register in regard to such cross examination, and in regard to calling witnesses in case none appear on the part of the creditors.

[Upon the question here presented, I beg to submit the following:

[The duty enjoined upon the register is to audit, not simply to adjudicate; to hear and examine, not on one side only, but on both sides. The duty is not only judicial but ministerial, administrative. I know of no statute or judicial writing in which the word “audit” is applied to the action of a court; ex vi termini, it implies executive as well as judicial action. If the act of auditing implied only judicial action, no more would be required of the register than that he take such evidence as the assignee, on the one hand, and the creditors, on the other, saw fit to submit, and pass upon the same, basing his decision upon such evidence alone. But an auditing officer proceeds to examine an account for the purpose of ascertaining in any way he may be able without regard to established forms or technical rules, what sum ought in fairness to be allowed. This is the course universally pursued by the auditing officers of corporations, civil or municipal, and it has grown into an established usage or custom. The word, as used in the act and general orders, is, no doubt, used in this accepted sense, as there is no other established sense in which it can be used. If this view of the case be correct, it is clear that the parties objecting to the item of Mr. Malcolm's claim do not suffer a default, or any consequence of a default, by not appearing before the register at the hearing, and urging their objections, nor for this omission on the part of the creditors is the duty of the register in any degree lessened or mitigated, but rather increased.

[But this view of the case places the register, in case of the non appearance of the objecting creditors, in a position which the profession do not readily accept. They inquire: “Who objects?” “Is the court to object to the items of the account it is sitting to pass upon?” “Is the register to act as court and counsel?” What I desire is, that these questions should be authoritatively answered and settled by the district judge. Experience has shown, that creditors simply in their character as creditors will rarely, if ever, appear, or in anywise interfere in the administration of an estate which the court has taken under its bankruptcy jurisdiction. The reason for this is clearly discernible in the provisions of the act itself. The English bankruptcy system, upon which our own is modeled, as well as the bankruptcy system of every other civilized country, is said to be “a system for the speedy distribution of the effects of an insolvent trader among his creditors.” The court, as its first act, seizes upon the estate of the debtor, brings it within its jurisdiction and control and there by charges itself with the duty of a just, full and complete administration of such estate in the interest of all concerned. Thus, duties, executive in their character, devolved themselves upon the judges of bankruptcy courts. And it was not until the practical operations of the system had effectuated at least four legislative revisions of the law, that parliament accepted the fact that creditors, as such, would not (for it was then, as it is now, altogether impracticable), so participate in the proceedings as to relieve the judges of the variant, and sometimes apparently conflicting, duties of a judicial and ministerial officer that a new class of officers were called into being who were especially charged with the administrative duties of the court. These officers were, as are the registers under our own act, deprived of the strict judicial function of deciding an issue duly framed, but upon them were devolved only those quasi judicial functions which our act calls “administrative duties.”

[Auditing the accounts of an assignee is clearly among these administrative acts, which pertain thus peculiarly to the register. But if the register has only to hear such testimony as may be offered on the part of the assignee on the one side, and by the creditors on the other, he ceases to be an administrative officer. and assumes purely judicial functions. And if the practice of the bar and the decisions of the court all tend in that direction, it is clear, that our bankruptcy system will soon be stript of all that distinguishes it favorably from the system of the collection of debts, which preceded it. That system required each creditor to 1029go into court with Ms individual claim, and prosecute that claim, in person or by attorney, under the penalty of its total loss, in case he failed at all times so to appear to prosecute the same. The multiplicity of suits of this character, and the immense labor and expense attendant upon them, in a country whose trade and commerce was so extensive as was that of England, led to the enactment in that country of bankruptcy laws as early as the year 1542. But, in the interests of “state rights,” we have been deprived in great part of this powerful and effective aid to commerce, until we are now compelled to accept of experiences, other than our own, to guide us in interpreting and administering our law. And if, under the influence of old habits, we permit the functions of these administrative officers to fall into disuse, we shall, instead of following the model we have adopted, which has been so useful in promoting the commercial interests of England, render our own act not only powerless for good, but so harmful to commerce, that its repeal will be demanded. Respectfully submitted.]2

BLATCHFORD, District Judge. In regard to the matters presented by the certificate of the register herein, of March 29th, 1872, the paper A, as referred to by Mr. Malcolm, may properly be regarded as evidence of what items of services Mr. Malcolm claims to have rendered and what disbursements he claims to have made, and as evidence of the items of alleged services and disbursements for which the assignee claims to be allowed, in his accounts, the sum of $893.86, as paid out by him to Mr. Malcolm. But the items all of them require to be explained, as to the occasion and necessity and value of the services, and the occasion and necessity and amounts of the disbursements, and how they came to be rendered and made, and whether they are, in any event, proper items for this account of the assignee, or whether they ought to be compensated through some other form of proceeding. The paper and its items, without such explanations, amount to nothing. So far as testimony given may explain any item in the above respects, that item and such testimony may be received in evidence together, for whatever together they may properly indicate.

The register's views in regard to his duty in auditing an account are correct.

The matter is remitted to the register for further proceedings.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.

, as paid register, which, I presume, means commissioner) amount to the sum of

, as paid register, which, I presume, means commissioner) amount to the sum of  , which added to the said sum of $250 amount to the sum of

, which added to the said sum of $250 amount to the sum of  . But, on the other hand, if the district judge shall be of opinion that the rejection of the bill, as evidence of the recitals there in contained, be correct, then, clearly, there is no evidence before me upon which an audit may be founded, and it will seem to be necessary to remit the case for further proceedings.

. But, on the other hand, if the district judge shall be of opinion that the rejection of the bill, as evidence of the recitals there in contained, be correct, then, clearly, there is no evidence before me upon which an audit may be founded, and it will seem to be necessary to remit the case for further proceedings.