Case No. 13,095.

SMITH v. PRIOR.

SAME v. O'CONNOR.

[2 Sawy. 461; 4 Fish. Pat. Cas. 469; 4 O. G. 633.]2

Circuit Court, D. California.

Sept. 1, 1873.

PATENTS—CONSTRUCTION OF CLAIM—STATE OF THE ART—USEFULNESS—FIRST INVENTOR—APPLICATION FOR PATENT.

1. The claim in a patent is to be construed liberally in favor of the patentee, and in connection with the specifications and accompanying drawings.

2. The claim must, also, he considered in connection with the state of the art at the time it is made.

3. The fact that the patented article has superseded all others before in use, and that the party charged with infringing has adopted it in the place of those before made and sold by him, constitutes strong evidence of usefulness.

4. The party who first invents and perfects the invention by producing a practical working machine, is entitled to a patent, even though another may have first conceived the general idea, and made some progress in its development short of constructing a practical machine.

5. The Culpin closet patented in England is not an anticipation of Smith's invention.

6. An application for a patent made within the two years required by the statute was rejected, the claim being defective and not covering the real invention. Another application was made within a reasonable time but not within the two years, upon the same specifications and drawings, with a corrected claim covering the invention, upon which a patent issued: Held, that under the circumstances the two applications, for the purposes of the two years, will be regarded as one continuous proceeding dating from the filing of the first application.

[Cited in Weston v. White, Case No. 17,459.]

[7. Cited in Buerk v. Imhauser, Case No. 2,107, to the point that damages in patent cases must be confined to the direct and immediate consequences of the infringement, and should not embrace those which are both remote and conjectural.]

[Final hearing on pleadings and proofs.

630[Suit brought upon letters patent [No. 106,080] for “improvement in water-closet receivers,” issued to William Smith, August 2, 1870. The claim and material parts of the specification are recited in the opinion.

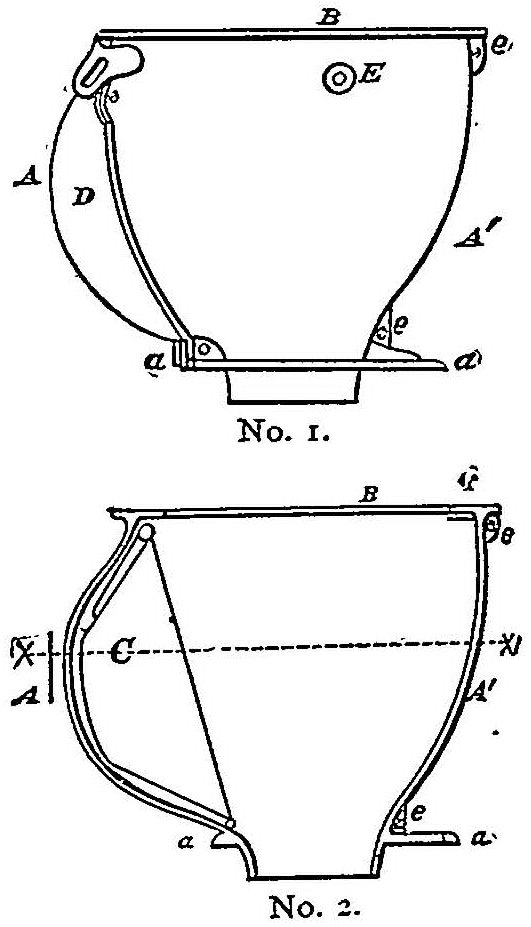

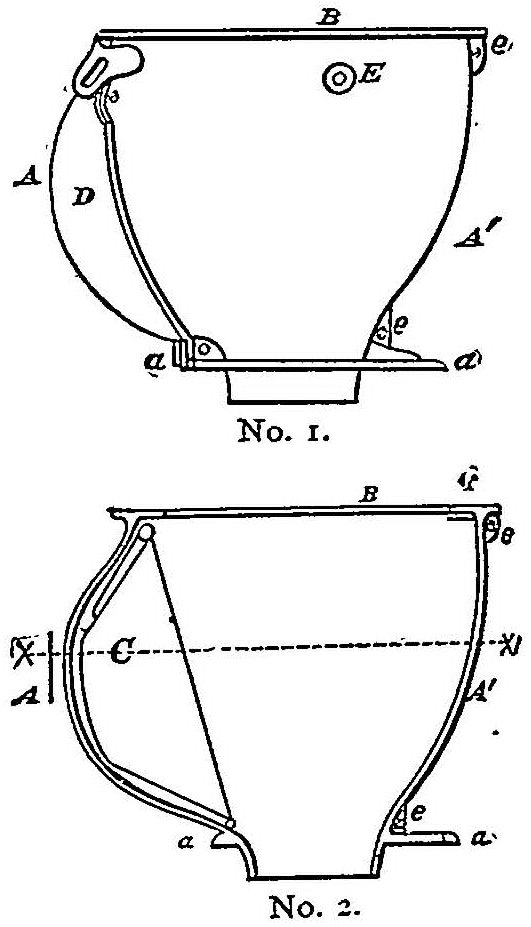

[In the above engravings, Fig. 1 represents a front view of complainant's device, as shown in his patent. Fig. 2 represents a vertical section of the same. These are referred to and described by letters of reference in the portions of the specification quoted by the court.]2

M. A. Wheaton, for plaintiff.

Alfred Rix, for defendant.

SAWYER, Circuit Judge. I have had some difficulty in reaching a satisfactory conclusion in these cases, and in rendering my decision, I shall very briefly mention some of the principal points involved.

One of the main points relied on by defendants is, that the specifications in the patent are insufficient to cover the claim of the plaintiff as now presented. It is insisted that the patent is for mere conformity, not for the form of the vessel, not for the change in the construction of the receiver of the water-closet. The language literally construed and the claim taken by itself may perhaps look so; but after considering the entire specifications and allegations, I think that this position is not tenable. The claim, it is true, might have been much better expressed, and it probably would be if the parties were to draw the specifications after this criticism. I recollect trying but few cases where similar objections have not been made to the patent, showing the difficulty of making specifications which shall cover exactly what the party designs they shall cover, and no more so as to render the patent free from criticism in that respect. In the description here, it is said: “The nature of my said invention consists in constructing the receivers of water closets, so that I am able to make the side where the pan is hung correspond to the shape of the pan, and thereby save the waste space which is left behind the pan in ordinary or common receivers. Heretofore the receivers or containers of pan-closets have been constructed of an oval bowl-shaped hopper, with a covering plate, having an enlargement on one side, into which the pan swings when emptying. This construction forms a large space inside the receiver, behind the pan, which is not utilized, but, on the contrary, is detrimental to the closet in allowing obstructions to collect and impede the working of the pan.”

Then there is a drawing given of the receiver as he claims his receiver to be, specifying each particular point, and, among others, he says: “AA represent the two parts of the receiver bolted together, with the pan hanging in it as open. It will be noticed that there is no waste space behind the pan; but that the receiver conforms to its shape,” going on and giving the particular description of each part of the instrument; and he further says: “By this mode of construction I am able to make a much more perfect article in form.”

Then he claims, “a receiver for pan water closets, formed and constructed so that the side AD, into which the pan C swings for emptying, will conform to the shape of the pan, and avoid the waste space behind the pan, as in ordinary or common receivers, substantially as and for the purpose set forth.”

It is true that he claims conformity in these parts, but that conformity is produced in the manner which he before described, wherein he gives a drawing, and gives each specific portion, and states the objects to be accomplished by his invention.

And then this space is to be saved substantially as and for the purposes indicated; that is to say, by means of the instrument in the form, and containing the parts before particularly described.

I think, therefore, it is a claim not merely for conformity, but conformity attained by the particular means which are here in the specifications set out, and shown in the implement of which he has given a drawing.

As I said before, that might have been more distinctly specified than it is, but taken together, and construed liberally in favor of the patentee, I think it substantially covers the case.

It is insisted, also, that the claim is too broad—that it covers the lower part as well as the upper part. I think that defect may be obviated by considering the entire application, although there is some difficulty in the description upon that point also. It is difficult to describe a matter of that kind distinctly 631in language, but the patentee has given, generally, the description of the closets before used, and the particular difficulties to be overcome. He has also given a drawing of his own implement. All definitions must pre-suppose some knowledge of the subject matter, or knowledge of the matters referred to in giving the definition, and, of course, a reference is made to the state of the art as it before existed here. Any one having to deal with these matters must be supposed to have some acquaintance with the subject matter, and the state of the art. A person, then, having a knowledge of the state of the art at the time, and taking the description together, would find the description sufficient, although it doubtless might have been better. From the construction which I have before indicated, I am inclined to think it is sufficient in that particular.

The next point is, as to whether the invention is useful or not—whether it attains any useful result. The testimony shows, and the claim is, that it is useful in several particulars. One is, that it dispenses with the space which in former closets existed behind and above the pan, and which was liable to clog up—fragments of paper getting behind and remaining there, and afterwards clogging the outlet. Some witnesses, it is true, say that they have never heard any such objection, while several witnesses on the other hand testify that that objection did exist; that it was a serious one; and that this change obviated it. The testimony is, also, that it takes less iron; that it reduces the size, and makes a saving in the matter of transportation; that it takes up less room; and all these, it is claimed, are useful results. Well, if all this is true, undoubtedly there is a useful result, and I think the testimony upon the whole shows it.

Besides that, there is the testimony that these closets have superseded all others. That of itself is very strong evidence that there is some useful result attained. More than that, parties are here contesting the use of this invention. The defendants here are using this form. If there were no useful result in it, there would be no occasion for them to be here contesting this invention. They can make and vend the closets they made before, if they are just as good. I think there is—that there must be—some useful result, and that these facts, in addition to the other testimony, ought to establish the point. I think there is a useful result, and that it is patentable in that particular.

The next objection is, that the defendants themselves first made a model in 1864, which is prior to the making of the machine by the plaintiff. There is testimony here tending to show that they did make some progress toward making the model, but the testimony also shows that they never reduced it to a practical working machine for some time afterward, after making the model and laying it aside; the party having gone to Europe in the meantime and returned. It was afterward taken up, but the plaintiff had in the meantime perfected his implement, and had made a practical working machine. I think on that score he is in advance of the defendants, and entitled to the patent as between him and them. With the defendants it was merely an undeveloped idea, so far as making a machine and putting it in practice is concerned.

It is contended that the Culpin patent in England is an anticipation. There is only one point on which it was contended that it is an anticipation, and that is, conformity in the pan, etc. I do not think that the Culpin machine is any anticipation of this. It is a different machine altogether, a machine of different form or make, and it does not appear that it was a practical working machine. At all events, it is a very different working machine from this, and I do not think it is an anticipation of this closet.

The next point presented is, that more than two years elapsed after the making and selling of this machine by the plaintiff before he made his application for the patent. If that is true—if the final application on which the patent was issued is to be taken as the date of the application—this point must be held good. He first made his machine in 1866. In 1866 he presented an application for a patent, but his claim in that application is different from the claim here; that is to say, the form of the claim. That application was rejected. The claim there is “constructing the receiver of a water-closet of two pieces, which are joined together, making a vertical joint, whereby I am enabled to make the receiver conform to the shape of the pan substantially, as herein shown and described.” Now, that was rejected on the ground that the claim was for casting in two pieces, and the casting of a machine in two pieces was not new. But the machine for which the claim was made was precisely the implement as finally patented. His descriptions were mainly the same, and his drawing was precisely the same as the one he now has, while the object to be accomplished was evidently the same as he desires to accomplish now. The description, among other things, says: “My invention consists in constructing the receiver in two pieces and bolting them together, whereby I am able to do away with the waste space behind the pan, and to save much expense in casting.” Now, one of the objects to be obtained, as is alleged, is to dispense with that waste space. His machine and drawings are the same. Then he says: “By this mode of construction I am able to make a much more perfect article in form, besides saving an important item in the weight of the casting and consequently of transportation.” Again. His claim is “constructing the receiver of a water-closet of two pieces, which are joined together, making a vertical joint, whereby I am enabled to make the receiver conform to the shape of the pan substantially, as herein shown and described.” The same ultimate object was to be accomplished 632by dispensing with the useless space. The same objects were to be accomplished then as now, but he stated his claim in a different form. It was the same machine he was seeking to patent.

Now, if the view which the patent office took is correct, that this claim was simply for casting in two pieces, and he had obtained a patent for that, it would not have covered the object covered by the present patent. The law in such cases prescribes what may be done where the patentee has failed to cover the points of his invention. He can surrender his patent and obtain another. It is the same invention, the same patent, the same drawings, but he has made an error in the presentation of his claim. He cannot only surrender once, but more than once; until his reissued patent covers his invention. It is manifest that the plaintiff here endeavored in all his applications to cover this invention—the same invention. He did not stop upon the rejection on the ground stated, but after some correspondence with his attorney, and some little delay in which he does not appear to be at fault, he presents his claim again in another form, and it covers, as he supposes, the same invention as that sought in his first application; and the commissioner of the patent office must have considered that he was presenting his claim for the same invention, but that he had made an error in his prior claim; otherwise he would not, under the circumstances, have granted his patent upon the second application.

I think it is the same machine, the same invention; a claim for the same thing that he sought originally—which is presented in the last claim; and that the different applications therefore connect themselves together for the purposes of the two years. That is to say, he made his application within the two years after he began to make and sell the machine; and although he failed to get his patent on his first application, for the reason given that the machine was not patentable, in the form in which he put it, he still renews his efforts, and files a new application for the same machine—the same invention—putting in his claim in a different form, and finally obtains the patent for the thing which he really invented, and under the decisions cited—one from the supreme court of the United States, and one from one of the circuit courts—I think his claims connect themselves together; that is, his application for his patent—the thing which he desired to obtain, which he conceived he had invented, when first made—is for the same machine as that for which he has finally obtained his patent upon a corrected application; and he sought to cover the same points in both applications. And he has followed it up, and the interval which elapsed between the rejection of the first and the filing of the later application, does not make a material delay in view of the explanation in the testimony relating to it. His counsel resided in New York at that time. The communication was by steamer. He began to correspond with his counsel immediately, and he followed the matter up, and finally succeeded in obtaining his patent. I think he has made the connection. The application for this invention is to be regarded as dating from the filing of the first application, he only changing the form of his claim.

These are the main points. There are one or two points I have some hesitation about, but I have concluded to give judgment for the plaintiff.

It only remains to consider the question of damages. That is always a difficult point in patent cases. I have taken into consideration the facts in relation to this class of closets and the prices which the plaintiff sold at before the defendants came into the market as competitors, together with the fact of the reduction of prices caused by competition, and the nearest I can come at it is to allow four dollars a closet; I think that is not extravagant. In the case of Smith v. Prior, the damages are $600; and in the case of Smith v. O'Connor, $632. I shall not, however, double or treble these damages in view of the fact that there is reasonable ground of contest between these parties.

2 [Reported by L. S. B. Sawyer, Esq., and by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here compiled and reprinted by permission. The syllabus and opinion are from 2 Sawy. 461, and the statement is from 4 Fish. Pat. Cas. 469.]

2 [From 4 Fish. Pat. Cas. 469.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.