Case No. 13,048.

SMITH et al. v. FRAZER et al.

[5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 543; 29 Leg. Int. 196; 3 Pittsb. R. 397; 2 O. G. 175; Merw. Pat. Inv. 121; 19 Pittsb. Leg. J. 154.]1

Circuit Court, W. D. Pennsylvania.

May 13, 1872.

PATENTS—ORE CRUSHER—NOVELTY—PROOFS—NOTICE.

1. A claim for introducing water into the pan of a stone-crushing machine to aid in disintegrating the rock and to cleanse and discharge the pulverized sand, the auxiliary and dependent relations of the water to the mechanism and its co-operative agency being fully set forth in the specification, embodies a patentable subject-matter.

2. The letters patent of John It. Smith. for improved machine for crushing and washing sand, granted August 27, 1867, are void for want of novelty.

3. Where the gate in a machine for crushing and cleansing gold ores had been placed in the side of the pan, above the bottom, with a view to discharging the water and lighter impurities, but retaining the gold: Held, that if it were desired to discharge the entire contents of the pan, this could so obviously be effected by extending the aperture to the bottom that the change would fall below the rank of on invention. To conceive and make it would require but a small amount of mechanical knowledge.

4. If in the notice of special matter relating to the novelty of the patented invention, the sources of defendant's proofs are indicated with such distinctness that the complainant can identify and resort to them, the purpose of that provision of the law which requires the defendant to give the “names and residences of those whom he intends to prove to have possessed a prior knowledge of the thing, and where the thing had been used,” is answered.

5. Where the defendants gave the name of certain mining establishments in a specified county as the places where the prior use of the invention had taken place: Held, that they had fairly supplied the complainants with the means of verifying their proofs, and had filled the measure of their legal duty.

[This was a bill in equity by john R. Smith and others against William E. Frazer and others.]

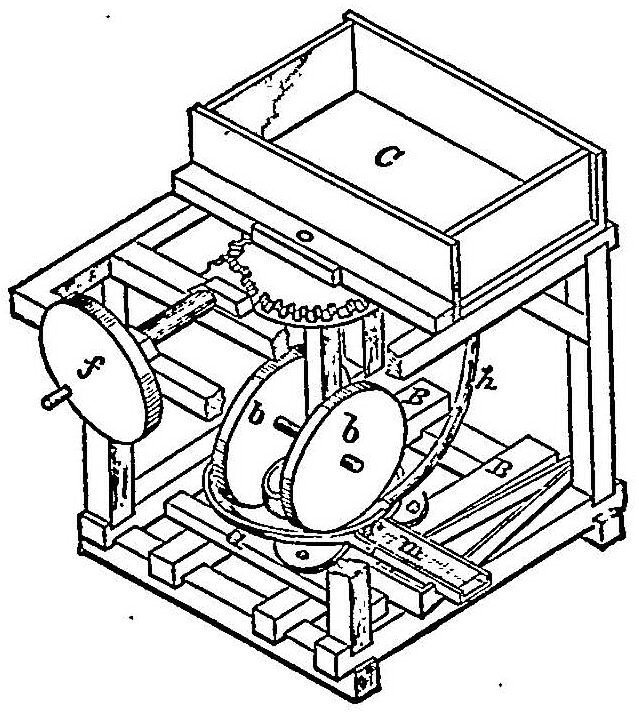

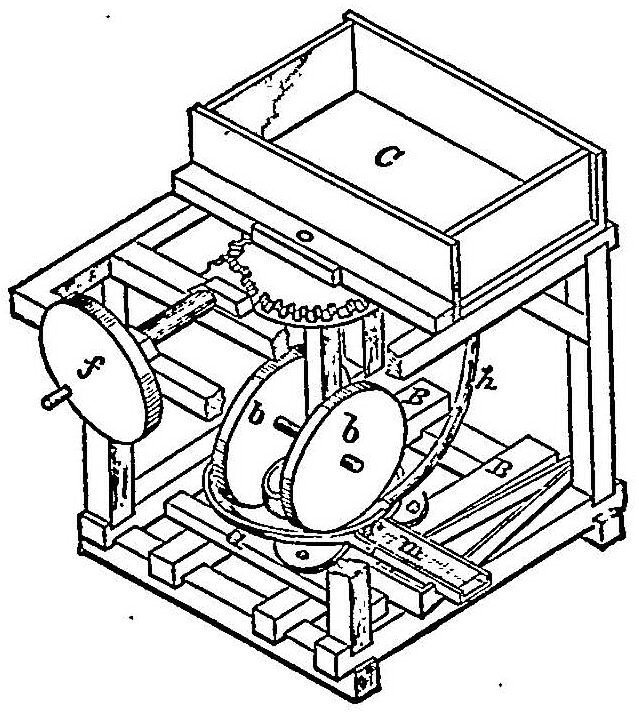

Final hearing upon pleadings and proofs. Suit brought upon letters patent [No. 682,481] for an “improved machine for crushing and washing sand,” granted to John R. Smith and William H. Denniston, assignees of John R. Smith, August 27, 1867. The invention will be readily understood by reference to the accompanying engraving, in connection with the claims, which were as follows:

1. The introduction of a stream or flow of water into the crushing-pan of a revolving sand, sand-rock, or sandstone-crusher, to aid the crusher or crushers in disintegrating the rock, and to cleanse and discharge the pulverized sand, substantially in the manner and for the purposes hereinbefore set forth.

2. The rotating and revolving crushing wheels b in a sand-rock crusher, in combination with a crushing-pan, a, provided with a

551

discharge-gate, s, and a water-supply pipe, h, or its equivalent, all constructed and operated substantially as and for the purposes above set forth.

Bakewell & Christy, for complainants.

John Mellon and John H. Bailey, for defendants.

MCKENNAN, Circuit Judge. The first claim of the patent in controversy is for the use of water as a detersive agent, in connection with the mechanism described in the specification. The functions of the water and its auxiliary and dependent relations to this mechanism, are fully set forth in the specification, which is expressly referred to and made part of the claim. Both are inseparable constituents of a method indicated for the production of a specific result. While each of them has its special office, the co-efficiency of all is expressly stated as necessary to effectuate the patentee's method.

By the words of the specification the patentee purposes to employ only the co-operative agency of water, and the patent must, therefore, be construed to claim, not its abstract functions, but the special mode in which, in connection with the mechanical devices described, its power is made available. In this view of the patent, the objection that the claim is for a subject not patentable, is clearly unfounded.

The second claim is for “the rotating and revolving crushing-wheels in a sand-rock crusher in combination with a crushing-pan provided with a discharge-gate, and a water supply pipe, or its equivalent, all constructed and operated substantially as and for the purposes set forth” in the specification. The invention, then, as here claimed, consists in the combination of the described devices. Each of them had been in use before, and unless the patentee's combination of them is new, and originated with him, he can not recover.

The first claim can not be sustained independently of the second, because, as the use of water in rock-crushing processes was not new, the patentability of its use must depend upon the novelty of the mechanical organization by which its efficiency is made available. Claimed, as it is, as merely an auxiliary agency in the method of operation set forth, the patentee can not assert an exclusive right to its use, except when employed as a coefficient with the mechanism with which he has inseparably associated it. Both claims must, therefore, stand or fall together.

The invention in question must not be confounded with that of a machine, or of an improvement in a machine, where a difference of operation is to be taken as establishing a difference of construction from previously existing machines. As before stated, it consists of a combination of specified mechanical elements, in aid of which water is used in producing the prescribed result. If the elements of the combination are shown to have been substantially embodied in a crushing machine previously constructed and used, the patent here can not be sustained.

Upon this point I regard the proofs as decisively against the complainants. To support this conclusion it is sufficient to refer to the testimony of Charles E. Seidel. While acting as superintendent of several mining companies in Louisa county, Virginia, and near Fredericksburg, Virginia, in 1848 to 1852, he used what are known as the Chilian mills for crushing and cleansing ores containing gold. These mills were constructed with two rotating crushing-wheels which revolved in a pan, provided with a hole in its side to wash the sand and debris away, and with a constant stream of water flowing into the pan. There can be no doubt, from the explanation given of their construction and mode of operation, that they are substantially identical with machines embodying the invention claimed by the patentee. It is true that their discharge-gate does not extend to the bottom of the pan, so that the gate was adapted to carry off the water with only the lighter impurities suspended in it. And such was its intended function where the machine was used for crushing and cleansing gold ores, and it was desired to retain the particles of gold in the pan; but where it is desired to discharge the whole contents of the pan, it could be so obviously effected by extending the aperture to the bottom that the change would fall far below the rank of an invention. To conceive and make it would require but a moderate degree of mechanical knowledge. Certainly it would evince no patentable merit, and can not, therefore, in any of its relations, be treated as within the protection of a patent.

This evidence is, however, objected to on the ground that the notice of special matter in the answer is not sufficiently specific. The act of congress requires notice to be given by a defendant of “the names and places of residence of those whom he intends to prove to have possessed a prior knowledge of the thing, and where the same 552had been used;” and the averment in the answer is, that prior knowledge of the invention claimed and of its use at the works of the Walnut Grove Mining Company, of the Louisa Mining Company, and of the State Hill Mining Company, all in Louisa county, Virginia, and at the works of the Vancieuse Mining Company, near Fredericksburg, Virginia, was possessed by Charles E. Seidel, residing in the city of Pittsburg.

In Latta v. Shawk [Case No. 8,116], Cincinnati was stated as the place of residence of the witnesses, and Cincinnati, Covington, Newport, Pittsburg, Philadelphia, and Wayne, county, Indiana, as the places of use; and the specification was held to be too indefinite, for the reason that it should name the street or factory where the patented structure was used, or that the name of the owner or person using it should have been given.

In Hays v. Sulsor [Id. No. 6,271], the court said: “This provision is designed to give the patentee the benefit of an examination into the facts of the supposed prior use. It has been ruled by the court that the notice given for this purpose in this case was defective in referring merely to the county in which the thing was used. This reference the court held was not sufficiently definite and explicit as to the place to fill the requirements of the spirit of the act.” The act was designed to secure the disclosure of specific facts, presumptively without the complainant's knowledge so that the patentee might be informed of the exact nature of the defense set up, and might be enabled to obtain full knowledge of all the facts and circumstances pertaining to it. Where prior knowledge and use are alleged, he must be informed of the name and residence of the person possessing such knowledge, and of the place where such use occurred. But it was not intended to dispense with the necessity of inquiry and research on the part of the patentee. The notice is only a guide to the sources of the defendant's proofs. If they are indicated with such distinctness that the complainant can readily identify and resort to them, the purpose of the law is answered. So in Phillips v. Page, 24 How. [65 U. S.] 168, where the notice set forth the name and place of residence of the person having knowledge of the prior use, and Fitchburg, Massachusetts, as the place of such use, Mr. Justice Nelson said: “The name of the person, and of his place of residence, and the place where it has been used, are sufficient. * * * With this information of the nature and ground of the defense, the plaintiff was in possession of all the knowledge enabling him to make the necessary preparation to rebut, that the defendant possessed to sustain it.” And in the cases cited by the complainant's counsel, above referred to, it is evident that the name of a street or factory in a populous city, or of a village or hamlet in a county, were regarded as sufficiently explicit to meet the demands of the act.

Now, in the present case, at least as much precision as these cases seem to require is observed. Not only is the name of the county furnished, but the localities within it of the prior use are precisely indicated by the names of three several mining establishments where it is alleged to have occurred. Thus the respondents have fairly supplied the complainants with the means of verifying their proofs, and have filled the measure of their legal duty.

The bill must be dismissed at the cost of the complainants, and it is so decreed.

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission. Merw. Pat. Inv. 121, contains only a partial report.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.