Case No. 13,045.

22FED.CAS.—35

SMITH v. FAY et al.

[6 Fish. Pat. Cas. 446.]1

Circuit Court, S. D. Ohio.

June, 1873.

PATENTS—MORTISING-MACHINE—ELEMENTS OF COMBINATION—SUBORDINATE DEVICE—NOVELTY—ANTICIPATIONS.

1. Patent for improvement in mortising-machines, granted Hezekiah B. Smith, January 10, 1854, construed and sustained.

2. The patent held to be for the combination of the power of reversing by friction, with a stop to arrest it, as distinguished from the specific devices.

3. This construction does not make it a patent for a principle.

4. The idea was new and highly beneficial, and deserves liberal protection.

5. The law demands no such strictness as that insisted upon by defendants, in reference to the employment of all the elements of a combination.

[Cited in Brickill v. Baltimore, 50 Fed. 276.]

6. A subordinate device is not an element within the rule applied to combination claims.

7. There are here but two elements.

8. When the instrumentalities described are used, by equivalent devices, operating in the same general way, for the same end, the patent is infringed.

9. When the idea is once suggested, and one mode of utilizing it pointed out, others are easily adopted.

10. The Holly machine held not to anticipate—First, on account of uncertainty as to what its principle was; second, on account of imperfect organization and imperfect power.

[Cited in American Bell Telephone Co. v. People's Telephone Co., 22 Fed. 313.]

11. The maker or workers of the Holly machine did not understand complainant's idea.

12. Holly's ignorance of it is shown by the fact that he, being a patent-man and dealer in machines, did not secure this improvement by a patent.

13. There is no such evidence on the point of time, as after twenty years' uninterrupted use of a valuable machine, should be supposed to antedate it.

14. The statute of limitations furnishes the philosophy for disposing of evidence of anticipations remote in date. In such cases a mere preponderance of evidence is not sufficient.

15. The presumption arising from silence is far stronger than preponderance in the number of witnesses.

16. Uncertainty as to the character of the machine adds greatly to the demand for certainty as to the time.

In equity. Final hearing on pleadings and proofs.

Suit [by Hezekiah B. Smith against J. A. Fay & Co. and others,] brought upon letters patent [No. 10,422] for “improvement in mortising-machines,” granted to complainant January 10, 1854, and extended seven years from the expiration of the original term.

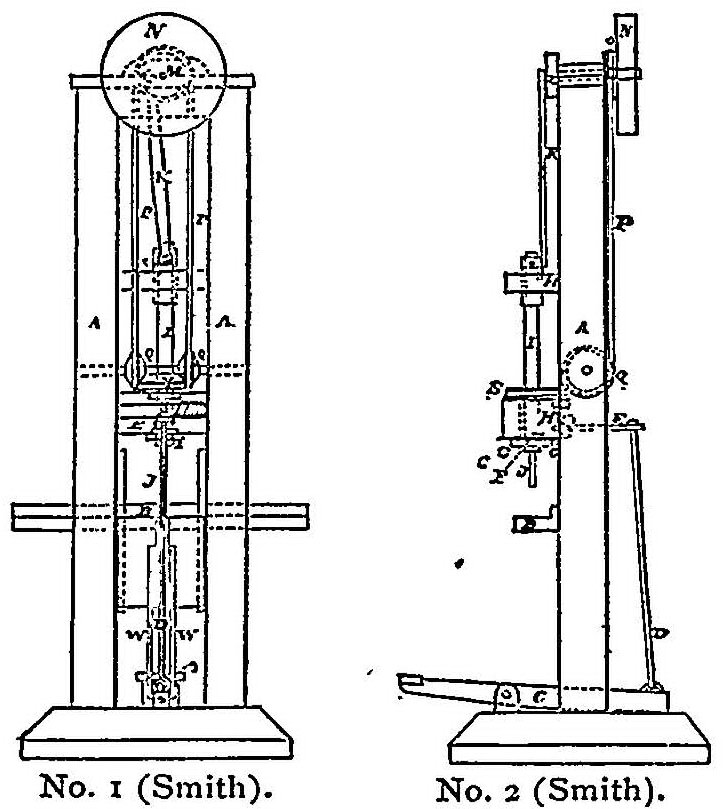

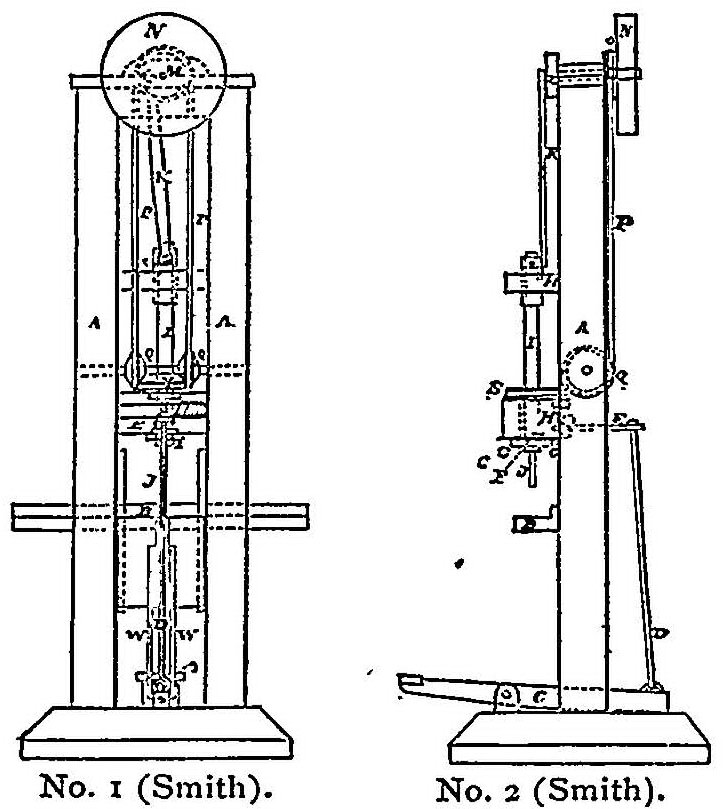

In the above engravings, Fig. 1 represents a back elevation, and Fig. 2 a side elevation, of the complainant's machine, as shown in his patent. The following is the substance of the specification, with the claim:

“The principal and main features of novelty in my mortising-machine consist of a combination so arranged and operated that the chisel is reversed by power (by friction, with band or other contrivance), and stopped in the required position to finish either head of the mortise. The stock to be mortised is to be placed upon the table, which can be seen at B. This table is connected to the treadle C by two rods, W. The operator, by placing his foot on the treadle C, and depressing the same, then the table B, together with the stock or wood to be mortised, will be raised until the chisel J penetrates or is forced in to it by the vertical movement of the piston I and chisel J, sufficient to give the required depth of the mortise; then the stock or wood is moved longitudinally—by the hand or otherwise—until the chisel arrives at one end of the mortise; then, by raising or removing the foot from the treadle C, the table B, together with the stock or wood to be mortised, is lowered so that the chisel is entirely free from the piece being mortised; at that instant the rod D depresses or lowers the out end of the arm or lever E, said arm being connected with the slide U, the said slide being connected with the said arm, so that, as the outside end of the arm is depressed, the slide U is raised sufficiently to disconnect it from the stop-pins G. attached to the reversing cylinder F, which then instantly 544reverses the chisel by means of the friction band P; the said chisel is not allowed to turn more than one-half of a revolution until the treadle C is again depressed and raised on account of the slide U, as it is raised from the stops G, and coming in contact with the tooth V, the said tooth Y is firmly secured to the reversing cylinder F. In the piston that holds the chisel there is a spline or guide-pin. This spline guides or governs the vertical movement of the piston and chisel by fitting to a slot in the reversing cylinder. By this arrangement, the reversing band P, and the reversing cylinder F, govern perfectly the reversing of the piston and chisel, and also allow the said piston and chisel to move up and down freely. The out end of the lever E is forced upward by a spiral spring, when the foot of the operator is placed on the treadle O, and depressed. The rod D, by being connected with the out end of the said treadle C, is raised through the hole in the out end of the lever E, thereby lowering the slide U, thereby stopping the chisel by the stop-pins G; on the reversing cylinder F coming in contact with the said slide U, by means of the ring seen at X, at the upper end of the piston, the said piston is allowed to revolve freely, and at the same time to move vertically, by means of a groove being turned near the upper end of the piston, and a steady pin or spline fitted to the said groove, and firmly secured to the ring X, it being understood that the said ring moves only vertically, while the piston moves vertically, and is revolved, or reversed, at the pleasure of the operator. The piston-stands H may be seen as attached to the frame A at H. The connecting rod may be seen at K, the crank at L, and the driving-pulley at N. The reversing band pulley is seen at O. At M may be seen the driving-shaft, and at O may be seen the friction rolls to guide the reversing band P. I have described the parts on which I base my claim much more thoroughly than the other parts of my improved mortising-machine, for the reason that the novelty of my improvement requires more explanation than the other parts that have been before known—all of which will be readily understood by inspection at the drawings. What I claim as my invention is the afore-described combination for reversing the chisel by power applied by friction (with band or otherwise), and stops operated so as to stop the chisel, when reversed in the manner essentially as set forth.”

The defendants, in their answer, make the following admission:

“These defendants, further answering, say that it is true that they have been and are extensively engaged in the manufacture and sale of mortising-machines at Cincinnati, Ohio, but they deny that they have ever made, used, or sold any mortising-machines containing the patented improvement, or any part thereof covered by the said patent, or which the said complainant claimed, or had a right to claim, as his invention. They say that, in some of their mortising-machines, the chisel was reversed by positive motion; that in others the chisel was reversed by a device which was described and claimed in letters patent No. 68,791, granted to defendants, J. A. Fay & Co., as assignees of John Richards and William H. Doane, September 10, 1867; and that others differed from those made in accordance with said patent No. 68,791, in the fact that the belt did not slip upon the pulley in the rear of the standard, when the chisel was at rest, but said pulley turned freely upon its axis; but when the chisel was permitted to turn, it was rotated by means of a leather washer interposed between the said pulley and a wheel on the end of the horizontal shaft.”

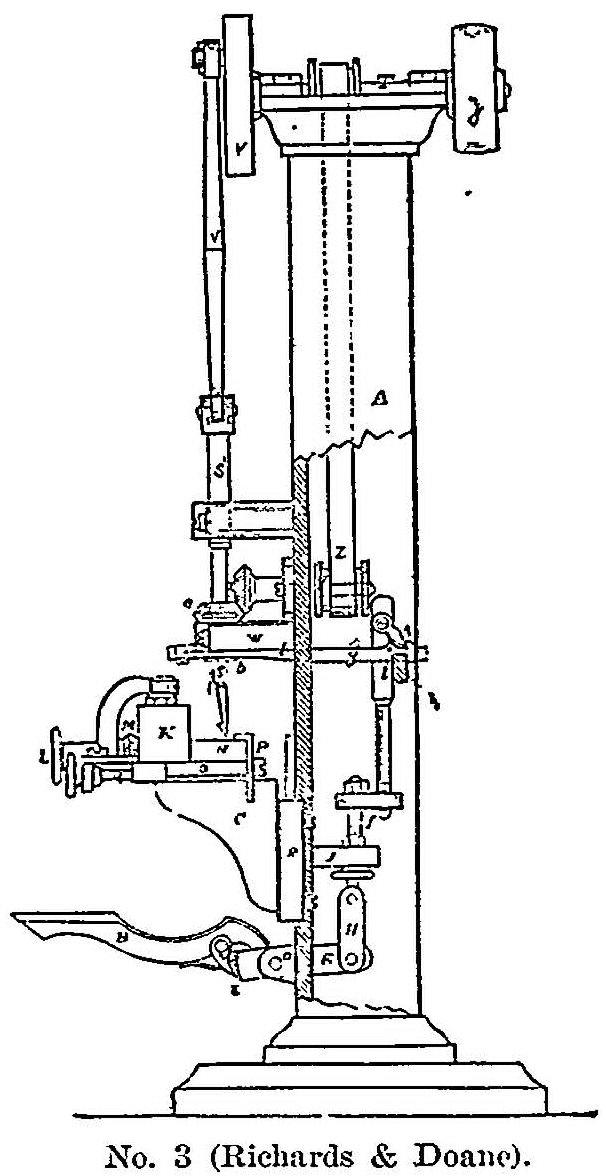

The accompanying engraving represents the Richards & Doane machine in side elevation, as shown in their patent of September

10, 1867. The substance of the following description is taken from their specification: “In Fig. 1, A represents the main column, forming the support on which the machinery is mounted, with the side removed to show the mechanism within. B is the treadle for operating the table C. It is hinged at D, and is adjustable at different heights by means of the pawl and ratchet shown at E, which determines its position with relation to the pivoted lever-piece F, and also regulates the throw of the table, which is moved by the link H and rod I, passing through 545stem J, which is fastened into the table C, and works in a slot in the front of the post A. K is a feed-roller, of India-rubber, or other similar material, and is revolved by hand-wheel L and bevel-gear M, the roll resting at the bottom on the face of the match-gear below, which is not shown in the drawing. N is a piece of wood being mortised, and is kept down upon the table-plate O, and in proper position, by means of the guard P, which adjusts to take pieces of different depths. The piece N is moved by the friction of the roll K, in either direction, to suit the length of mortise required. Screw Q is to adjust the roll K. The main table support C is pivoted on the plate It, so as to form angular mortises. S is the chisel-bar, receiving motion from shaft T by means of crank-wheel U and pitman V. S2 is a shell, carrying the lugs t t, in which the bar S revolves by means of the reversing device at the lower bearing W, consisting of the gearing X, pulley Y, and belt Z. The hub of the gear a forms a shell around the chisel-shaft S, and passes down through the bearing at W, having a feather or spline for revolving the bar S.”

Judge Emmons, at the time of delivering his opinion, had sketched it in brief, intending to elaborate it afterward. The state of his health prevented his doing so, and the opinion, as given below, is taken almost literally from this sketch, with only such insertions of data and slight changes in the phraseology as were necessary to make it intelligible, and could be made from the record, without in any way modifying the force of the language used.

Charles B. Collier, for complainant.

Fisher & Duncan, for defendants.

EMMONS, Circuit Judge. The court is of the opinion that defendants' machine infringes complainant's patent. We do not suppose they would seriously deny this if the claim is held to be for the combination of the power of reversing by friction, with a stop to arrest it, as distinguished from the specific devices. It is held to be for this. With any other construction, the patent would be of little value. It is so construed by two experts, whose testimony in this particular is uncontradicted. The court would, from an examination of all the devices in evidence and of the state of the art, reach the same conclusion. This construction does not make it a patent for a principle. The defendants certainly employ the idea of the patent. This idea was new and highly beneficial, and deserves liberal protection. The adjudications upon the doctrine of equivalents warrant such protection.

Although the court can not follow fully the precise distinctions taken” by complainant, the law demands no such strictness as that insisted upon by defendants in reference to the employment of all the elements of a combination. Their error lies in the use of the term “element.” A subordinate device is not, within this rule, an element. There are here but two elements—the constantly acting power by friction to effect the rotation, and the “automatic engagement and disengagement of stops.” These are protected, so far as the instrumentalities described and their equivalents are concerned, and when these are used by equivalent devices co-operating in the same general way, for the same end, the patent is infringed. Overlooking all literalisms and dicta, the facts of the case, and what has been actually administered in the current of cases, compel the judgment given on this point. When this idea is once suggested, and one mode of utilizing it pointed out, others are easily adopted.

Were it necessary, we should say that the Holly machine did not in principle antedate the patent: first, on account of the uncertainty as to what its principle was; and, second, on account of its imperfect organization, want of success, and practical power.

We do not, in this, overlook what some witnesses say about its efficiency; but it went out of use. Those who contrived and worked it did not understand complainant's idea. Holly did not understand it or patent it. The reason he assigns for not patenting it is absurd, in view of the law, and his belief that he had invented so valuable a device. He was a patent-man, and knew his rights. He was a dealer in machines, and would have secured this improvement if it had been his. What he patented is what he before made, after he had perfected it. It was not the device described by the witness. Mistakes in this regard are not only probable, but morally certain.

But we find no such evidence, or approach to such evidence, on the mere point of time, as after twenty years' uninterrupted use of a valuable invention should be supposed to antedate it. The danger of such proof generally must be considered. The accident of discovering the engraving saved complainant from innocently using false evidence, and is conclusive on the point of time. The witnesses swore positively on this point, and are all conclusively contradicted. Westcott, of all men, ought to know whether he first used the Holly machine in 1853 or 1852. He refers to data from the iron-works books. His whole evidence is worth no more than theirs, and they, in the opinion of the court, fully contradict his conclusions from them, and all others who swear to a manufacture in 1851 and 1852. Had they been made then, the books would have disclosed it. No entries on them before 1854 have any plausibly certain connection with such a machine. These books do show pretty fully other machines. But Holly himself, although literally dating in 1852, is substantially uncertain. No witness fixes the time in a mode, or by a reference to facts, which show him dishonest, if wrong. Whenever a date or fact is fixed, the nature of the conditions show that it might just as well have been afterward. There is in no instance 546a necessary connection. This is illustrated by cases cited by complainant on the question. The statute of limitations furnishes the philosophy for disposing of such a case. There may be cases where the proof is beyond criticism and without conflict. In such cases this rule does not apply; but, if there is any doubt, a mere preponderance of evidence is not sufficient. If this were sufficient, the same rule would apply as if recent facts were in issue. The presumption arising from silence, where there is so much interest to assert, an occasion to assert it, and the party intelligent, and the results certain, if the facts warranted it, has far more strength than any preponderance in number of witnesses and literal statements made by them in this case. Uncertainty as to the character of the machine adds greatly to the demand for certainty as to the time.

Decree for injunction and account.

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.