Case No. 12,687.

21 FED. CAS.—71

SEYMOUR et al. v. MARSH et al.

[6 Fish. Pat. Cas. 115;1 2 O. G. 675;9 Phila. 380; 29 Leg. Int. 357; 4 Leg. Gaz. 346.]

Circuit Court, E. D. Pennsylvania.

Oct. 25, 1872.

PATENTS—REISSUE—NOVELTY—EXPERIMENTS—HARVESTERS.

1. The rule for determining the validity of a reissued patent restricts the inquiry to a comparison of the terms and import of the original and reissued letters, and a consideration of the patent office drawings and model. If, from these, it results that the invention claimed in the reissue is substantially described or indicated in the original specification, drawing, or model, the very case for which the act of congress was intended to provide is shown to exist, and any change in the description or claims, which is necessary to effectuate the invention, is within its sanction.

2. Under the rule laid down by the supreme court, in Seymour v. Osborn [11 Wall. (78 U. S.) 516], if the inventions claimed in the reissue were suggested or substantially indicated in the original Specification, it is clear that the specification of the reissue may be amended so as to fully describe them, and the claims enlarged so as distinctly to embrace them.

3. It is no objection to the validity of reissues that their claims are broader than those of the original patents.

4. The allegation of want of novelty can not avail the defendants unless it reaches back to the date of the original patent, and is founded upon proof that the invention then indicated was not novel. It certainly can not be invoked against the authority of the commissioner to allow an amended specification, and to grant a reissued patent upon it. And upon this ground alone can a reissue be adjudged to be ultra vires.

5. If a machine, taken as a whole, in its construction and operation, is an advance upon the state of the art to which it appertains, furnishing a better method of performing a useful function than was before available, it is not to be discarded as destitute of patentable merit.

[Cited in Broadnax v. Central Stock Yard & Transit Co., 4 Fed. 216.]

6. When one witness testifies to a single machine constructed by Hussey, in the fall of 1848, having a quadrant-shaped platform, and there is other evidence, not however beyond the reach of criticism, tending to show that such a platform was attached to more than one machine, but there is no additional evidence that machines thus constructed were actually used and were successfully operative: Held, that these machines must be treated as experiments, in nowise affecting the novelty of the complainant's invention.

7. Reissued letters patent Nos. 72, 1,682, and 1,683 held valid, and infringed by defendant's machines.

[These were two suits in equity, by William H. Seymour and Dayton C. Morgan, against James S. Marsh & Co., of Lewisberg, Pa., and Marsh, Grier & Co., of Williamsport, Pa., respectively, for the infringement of the Seymour patent and the Palmer and Williams patent. The causes are numbered, respectively, 33, June term, 1871, Western district of Pennsylvania, and 30, April term, 1871, Eastern district of Pennsylvania, and are now before the court on final hearing upon pleading and proofs.]

Suits brought upon letters patent [No. 8,192] granted Aaron Palmer and S. G. Williams, July 1, 1851, for improvements in grain-harvesters, reissued April 10, 1855, as No. 305—again reissued January 1, 1861, as reissues 4 and 5; No. 5 being reissued May 31, 1864, as No. 1,682, and extended July 1, 1865, for seven years; also, upon letters patent granted William H. Seymour, July. 8, 1851, for “improvement in reaping-machines,” reissued July 10, 1860, in three divisions, two of which were again reissued—No. 1,003 on May 3, 1864, as reissue No. 1,683, and No. 1,005 on May 7, 1861, as reissue No. 72. No. 1,683 and No. 72 were extended July 8, 1865, for seven years.

The claim of the Palmer and Williams patent, No. 1,682, is: “The combination of the cutting apparatus of a harvesting-machine, with a quadrant-shaped platform, arranged in the rear thereof, and a sweep-rake, operated by mechanism, in such manner that its teeth are caused to sweep over the platform in curves, when acting on the grain, these parts being and operating substantially as set forth in the specification.”

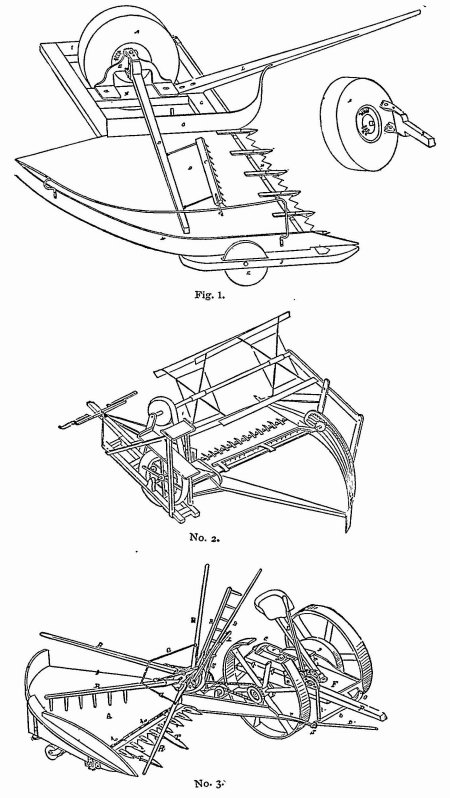

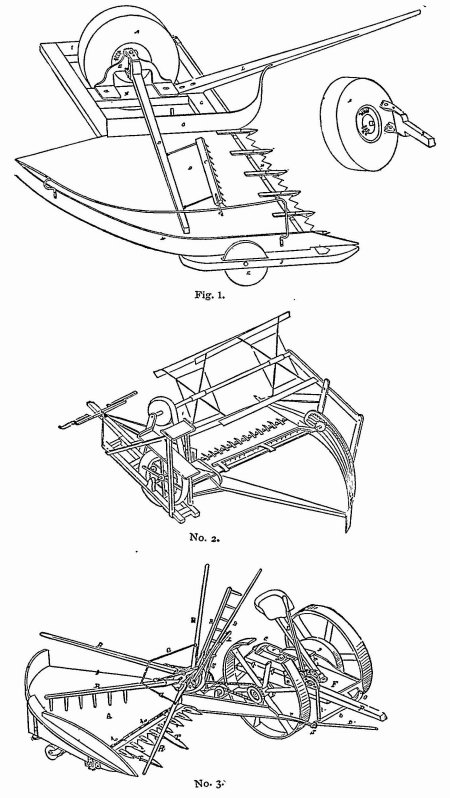

Fig. 1, taken from the drawings of the Palmer and Williams patent, represents the devices covered by the claim, and will be readily understood in connection therewith.

The claim of the Seymour reissue, No. 1,683, is: “The combination in a harvesting-machine, of the cutting apparatus with a quadrant-shaped platform in the rear of the cutting apparatus, a sweep-rake mechanism for operating the same, and devices for preventing the rise of the rake-teeth when operating on the grain; these five members being and operating substantially as set forth.”

The claim of Seymour reissue, No. 72, is “A quadrant-shaped platform, arranged relatively to the cutting apparatus, substantially as described and for the purpose set forth.”

Fig. 2 represents the device claimed thus broadly in reissue 72, and in combination in reissue 1,683.

Fig. 3 represents the device used by the defendants. It was patented to James S. Marsh, February 28, 1871.

It has the quadrant-shaped platform A, over which an automatic revolving-rake, R, sweeps from the cutter to the place of delivery. It also has directing grain-guides, B B, to direct the standing grain toward the draft-frame.

The questions presented to the court were very similar to those decided by the supreme-court, in the case of Seymour v. Osborn, 11 Wall. [78 U. S.] 516,

1118[Figure 1 is from drawings of reissued patent No. 1,682, granted May 31, 1864, to Palmer and Williams, published from the records of the United States Patent office.]

where the state of the art is very fully illustrated by the reporter in the statement of the case.

The patents sued on were the same in each case.

Henry Baldwin, Jr., and George Harding, for complainants.

J. W. Maynard and J. O. Parker, for defendants.

MCKENNAN, Circuit Judge. On July 1, 1851, letters patent were granted to Aaron Palmer and S. G. Williams, for “improvement in grain-harvesters.” This patent was reissued in divisions, one of which was numbered 1,682, which was extended for seven years from July 1, 1865.

On July 8, 1851, William H. Seymour obtained a patent for an “improvement in reaping-machines,” which was also reissued in divisions; two of which were numbered 72 and 1,683, and were extended for seven years from July 8, 1865.

The title to these several reissued and extended patents, 1,682, 72, and 1,683, has been duly vested in the complainants, and they constitute the subjects of the present contention.

These patents embrace several claims, the three following of which only are the defendants charged with having infringed:

1. The claim of 1862, which is for a combination of the cutting apparatus of a harvesting-machine, with a quadrant-shaped platform, arranged in the rear thereof, and a sweep-rake operated by mechanism in such manner that its teeth are caused to sweep over the platform in curves when acting on the grain, these parts being and operating substantially as set forth in the specification.

2. The claim of No. 72, for a quadrant-shaped platform, arranged relatively to the cutting apparatus, substantially as described, and for the purpose set forth.

3. The claim of 1,683 for “the combination, in a harvesting-machine, of the cutting apparatus with a quadrant-shaped platform in the rear of the cutting apparatus, a sweep-rake mechanism for operating the same, and devices for preventing the rise of the rake-teeth when operating on the grain; these five members being and operating substantially as set forth.”

The defendants resist the complainants' right to a decree upon the grounds that the reissued patents are invalid; that the inventions claimed are not novel; that such inventions will not work practically; and that they are not infringers.

The rule by which the validity of reissued patents is to be determined, is well defined and familiar. It restricts the inquiry to a comparison of the terms and import of the original and reissued letters, and a consideration of the patent office drawings and model. If, from these, it results that the invention claimed in the reissue is substantially described or indicated in the original specification, drawing, or model, the very ease for which the act of congress was intended to provide is shown to exist, and any change in the description or claims, which is necessary to effectuate the invention, is within its sanction. In Seymour v. Osborn, 11 Wall. [78 U. S.] 544, the court say: “Power is unquestionably conferred upon the commissioner to allow the specification to be amended, if the patent is inoperative or invalid, and in that event to issue the patent in proper form; and he may, doubtless, under that authority, allow the patentee to re-describe his invention, and to include in the description and claims of the patent, not only what was well described before, but whatever else was suggested or substantially indicated in the specification or drawings, which properly belonged to the invention, as actually made and perfected.”

Now, if the inventions claimed in the several reissues in question, were suggested or substantially indicated in the original specification, it is clear that the specification might be amended so as to fully describe them, and the claims enlarged so as distinctly to embrace them.

To ascertain this, it is altogether unnecessary to institute a comparative analysis of the original and reissued patents, because it is plain, upon inspection, that the quadrant-shaped platform, arranged as described, claimed in reissue 72, and the combinations claimed in 1,682 and 1,683, are represented in the descriptions and models, and illustrated by the drawings filed with the original applications, and because this is distinctly proved by the defendants' expert witness, Homer P. K. Peck. This being so, it is no objection to the validity of the reissues that their claims are broader than those of the original patents; or that, in view of the state of the art, these claims are broader than the patentees' invention. The very object of the act of congress is to authorize such enlargement of the description and claims of the reissue, as to cover the invention indicated in the original, and the latter branch of the objection can only affect the reissue by avoiding the original patent for want of novelty of the invention. It can not avail the defendants, unless it reaches back to the date of the original patent, and is founded upon proof that the invention then indicated was not novel. It certainly can not be invoked against the authority of the commissioner to allow an amended specification and to grant a reissued patent upon it. And upon this ground alone can a reissue be adjudged to be ultra vires.

That a machine, when first applied in practice, does not perfectly accomplish the work for which it was designed, or does not accomplish all that its inventor supposed it would, is not enough to secure its rejection as a patentable invention. Correction of defects, arising from imperfect material and not involving reorganization of the machine, 1120will not change its fundamental character, and subject it to condemnation as impracticable in its original condition. Taken as a whole in its construction and operation, if it is an advance upon the state of the art to which it appertains, furnishing a better, though still imperfect method of performing a useful function, than was before available, it is not to be discarded as destitute of patentable merit. The proofs in this case show no more than that, when the complainants first put their machine in operation, some of its parts were unequal to the strain upon them, and the rake was not heavy enough to hold itself steadily in the gavel. The weak parts were strengthened, and a spring was added to hold the rake down, and the proof is plenary, that then a large number of machines was made and sold, and that they were successfully operative.

It is said, however, that this was a remodeling of the machine, and that it was not then the same machine described in the patent. But there was not the least change in its organization. It embodied still the precise devices and combinations claimed in the patents, arranged as there described, with only such amendments as were conducive to its more perfect efficiency. If any one else had constructed a reaping-machine, with a quadrant-shaped platform and the combination of elements claimed by the patentees, and had made the jaws, by which the rake is operated, of sufficient strength to bear the strain upon them, and had applied a spring or other device to hold the rake down, can there be any doubt that he would be an infringer? He would be rightly so treated, for the reason that he had appropriated the combinations claimed by the patentees, and that the changes made by him did not constitute a new or different invention. The same effect only is due to the acts of the patentees, and while they have retained the constituents and organization of their invention, they have made it more efficient in operation by strengthening its weaker parts, and by the use of auxiliary mechanism, to hold the rake steadily in its place. It is clear that by so doing the identity of their invention has not been changed, nor has it been abandoned, or withdrawn from the protection of their patents. Nor is this conclusion to be repelled by the speculative opinions of experts, mechanical or professional, that the invention, as described in the original specification, would be impracticable. Founded, as they are, upon a very literal and narrow construction of the patent, they are of but little value when weighed against the demonstration of actual results.

The novelty of the inventions in question is contested upon the ground that they were anticipated by the attachment of a circular platform to a McCormick reaper by Brinckerhoff, by the construction of Burrall reapers by Joseph Hall, and by machines constructed by Piatt, McCormick, and Hussey. Of the two first of these, it is only necessary to say that the weight of evidence is decidedly against the fact testified to by Brinckerhoff, and that the construction of Burrall reapers by Hall, prior to the complainants' invention in 1849, is satisfactorily disproved.

The other exhibits were before the supreme court, in the case of Seymour v. Osborn, 11 Wall. [78 U. S.] 516, in which the same patents involved in this case were in controversy; and were fully considered and examined by the court. Although the judgment pronounced is not conclusive in this case, yet the opinion of the court, even as to matters of fact, is entitled to the respect which is due to the high character of the tribunal, and to its careful analysis of the proofs; and especially ought it to be accepted as definitive in this court, when I have heard no argument to produce a doubt of the soundness of its conclusions, or to lead me to suppose that they would not be reasserted upon the evidence in this case. I must, therefore, hold that the Piatt & McCormick reapers did not embody the complainants' inventions, and do not disprove their novelty. Additional evidence has been produced in this case in reference to the construction, by Hussey, of reapers with a quadrant-shaped platform. In Seymour v. Osborn the proof was that one machine only, embracing this feature, was constructed by Hussey, in the fall of 1848, and it was adjudged by the court to be an experiment, which was abandoned. Thomas J. Love-grove, who was examined as a witness in that case, and omitted all mention of a quadrant-shaped or curvilinear platform in a Hussey machine, testifies now that Hussey attached to the back of the platform of some of his machines, an additional angular piece, which finally developed itself, in 1847 or 1848, into a part of a circle, the guide-board being sawed so that it could be easily bent. He was reminded of this, after the lapse of more than twenty-three years, by reading the depositions of the two witnesses who testified in regard to the Hussey machine in Seymour v. Osborn. Even if such remarkable obliviousness, and such a lapse of time, do not impair the credibility of his testimony, he is altogether indefinite as to the number of machines made with the curvilinear attachment, or as to the fact that any one of them was sold or used. The only one of which he speaks with any distinctness is the old returned machine at Hussey's shop in Baltimore, to which evidently the testimony in Seymour v. Osborn related. But he has no recollection of ever seeing this machine or one like it in use.

The question then stands just as it did in Seymour v. Osborn, except that there is evidence, certainly not beyond the reach of criticism, tending to show that a curvilinear platform was attached to more than one machine, but there is no additional evidence that machines thus constructed were actually 1121used and were successfully operative. There is no reason, therefore, why the deductions of the court in that case are not just as appropriate to the evidence in this. Thus applying them, these machines must be treated as experiments, in nowise affecting the novelty of the complainants' invention.

It is earnestly contended that the machines constructed by the respondents do not infringe the patents of the plaintiffs. The argument is rested mainly upon the fact that the mechanism employed in the machines constructed by the defendants, is different from that described in the patents. This is undoubtedly true, and so it was also in Seymour v. Osborn. But the question is not as to the identity of the actuating forces, but whether the devices and combination of devices claimed by the patentees, are embodied in the defendants' machines and operate to produce the same result in substantially the same way.

Now, in these machines is to be found a quadrant-shaped platform, annexed relatively to the cutting apparatus, as is described and claimed in reissued patent No. 72.

There is also to be found the combination claimed in No. 1,682, viz., of the cutting apparatus, with a quadrant-shaped platform arranged in the rear thereof, and a sweep-rake operated by mechanism, so that its teeth are caused to sweep over the platform in curves when acting on the grain. And there is also to be found the combination claimed and described in No. 1,683, of the cutting apparatus, with a quadrant-shaped platform in the rear thereof, a sweep-rake, mechanism for operating the same, and devices for preventing the rise of the rake-teeth when operating in the grain.

This combination embraces the three elements which compose the other, and its merit consists chiefly in the value and novelty of the results accomplished by it. That result is the automatic removal of the grain, as it is cut, from the platform, and its delivery crosswise upon the ground, and out of the way of the team or machine when cutting the succeeding swath. The same result is produced by the defendants' machine; but do the mechanical agencies employed operate substantially in the same way with those described in the patents? Rakes, similar in construction, are used in both the complainants' and defendants' machines, but in the complainants', the rake has a vibrating or reciprocating motion, while in the defendants' it has a revolving motion. This is said to constitute a material difference of operation. But it is to be observed that the essential function of the rake is to sweep over the platform in the arc of a circle, thereby discharging the cut grain at the rear of the platform, so as to be out of the way of the team and machine on their next round. If this function, then, is performed in the same way in both cases, as it manifestly is, what matters it whether the rake is made to move from the rear to the front of the platform to resume its appointed work in a horizontal line or in the orbit of a circle? In neither case is there any difference in the result or the essential method of effecting it, and there is, therefore, no noticeable difference in operation.

The complainants' patent having expired, they can have a decree for an account only. To this they are entitled, and it will accordingly be entered.

[NOTE. A further decree was made ordering a reference to a master. Exceptions made to this report were overruled by the circuit court. Case unreported. To the award of damages made by the circuit court, both parties appealed to the supreme court, where the decree was affirmed. 97 U. S. 348.

[For other cases involving this patent, see note to Seymour v. Osborne, Case No. 12,688.]

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.