Case No. 12,166.

21FED.CAS.—6

RUSSELL & ERWIN MANUF'G CO. v. MALLORY et al.

[10 Blatchf. 140; 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 632; 2 O. G. 495; Merw. Pat. Inv. 439.]1

Circuit Court, D. Connecticut.

Sept. 17, 1872.

PATENTS—CONFLICTING CLAIMS—REVERSIBLE LATCH—ABANDONMENT—PUBLIC USE AND SALE.

1. A patent was granted to W., in 1867, (applied for in 1865,) with a claim identical with that contained in a patent granted, in 1864, to M. In a suit in equity, brought by W., against M., for infringing such claim, the answer of M. insisted on the validity of such claim in the patent to M.; Held, that M. could not, on the hearing, take the ground that the claim of the patent to W. did not claim patentable subject matter.

2. The claim of the letters patent granted to Rodolphus L. Webb, December 31st, 1867 for “improvements in reversible locks and latches,” namely, “The combination of a lock and latch, when the latch bolt and its operative mechanism are arranged in a case or frame independent of the main case, and constructed so that the latch bolt may be reversed, substantially as described, without removing the said independent case from the main case,” is not open to the objection that it claims merely the combination of a lock and latch, and so claims merely the aggregation of two things which have no relation to each other, in performing their separate functions, and which are not patentable, as a combination.

[Cited in Russell & Erwin Manuf'g Co. v. P. & F. Corbin Manuf'g Co., Case No. 12,167.]

3. The claim does not claim, as an invention, the combination of a lock with a latch, but claims a reversible latch, constructed as described to be used in connection with, and enclosed by, the lock case.

4. Mere lapse of time, before an inventor applies for a patent for his invention, does not, per se, constitute an abandonment of the invention to the public.

[Cited in Andrews v. Carman, Case No. 371.]

5. The question of abandonment, whether in regard to the time prior to two years before the application for the patent, or to the time included in such two years, is a question of fact.

[Cited in Andrews v. Hover, 124 U. S. 710, 8 Sup. Ct. 681.]

6. An inventor is not required to put his invention into public use before lie applies for his patent.

7. Mere public use and sale of an invention, before a patent for it is applied for does not invalidate the patent, unless the public use and sale were with the consent and allowance of the inventor.

[Cited in Andrews v. Hovey, 124 U. S. 710. 8 Sup. Ct. 681.]

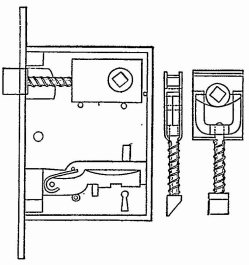

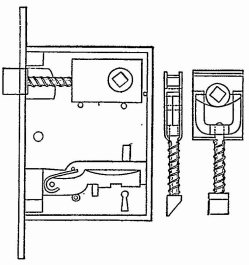

[Final hearing on pleadings and proofs. Suit brought upon letters patent [No. 72,946], for “improvements in reversible locks and latches,” granted to Rodolphus L. Webb, December 31, 1867, and assigned to complainants. The invention is illustrated in the accompanying diagram.

[The left-hand figure represents a case containing an ordinary lock mechanism in the lower part, and, in the upper part, the reversible latch shown in the two detached views on the right. This latch is so formed by inclosing, the inner end of the latch bar, with the arms and hub in a thin case, as shown, that the case may be placed within the main case of the lock, between the two plates thereof, so as readily to slide a short distance forward or backward. The knob spindle being removed, the whole case may be drawn forward by applying the thumb and finger to the projecting end of the latch until the square portion is clear of the external mortice in the case, when the 79latch may be turned half round, pushed back, and held in place by inserting the spindle. The latch may be thus adapted to a right or left-hand door.]2

C. E. Mitchell and Benjamin F. Thurston, for plaintiffs.

Charles F. Blake and Charles R. Ingersoll, for defendants.

WOODRUFF, Circuit Judge. The bill of complaint herein sets out a patent for “improvements in reversible locks and latches,” granted, December 31st, 1867, to Rodolphus L. Webb, and by him assigned to the plaintiffs, May 12th, 1868, and alleges that the defendants have infringed, and are still infringing, that patent, by the manufacture and sale of locks and latches constructed, in substance, according to the invention patented. It prays an injunction and an account of profits.

The answer denies that Webb was the first inventor, and alleges that the defendant Burton Mallory was the first inventor of the said improvement, and that he obtained letters patent therefor June 7th, 1864. It admits that the defendants have made and sold reversible latches constructed in accordance with the said letters patent, and are intending to continue such manufacture, but denies that therein they infringe any rights of the complainants. By an amendment of the answer, the defendants further aver, that, if it shall appear that Webb was the first and original inventor of the reversible latch described in the letters patent issued to him, the said invention was, before his application for letters patent, abandoned, and no steps were taken by him to bring his invention into public use until after the said Burton Mallory had, by his original invention, discovered the said improvement and taken out letters patent therefor, and the defendants had, by their diligence, at large expense and great effort, given to the public the benefit of said invention, by placing the said improved latches on sale in the principal markets of the United States; that said Webb, for many months before his application for the letters patent issued to him, knowingly, and without objection, permitted said Mallory and the defendants to use the said invention, and to make and sell in the various markets of the United States large quantities of latches constructed according to said invention; that the complainants are, by reason thereof, estopped from asserting any right under the said letters patent, and from denying the right of the defendants to use the said invention; and that, by such abandonment, negligence and laches, the said Webb forfeited any right he otherwise might have had to the said letters patent, and the same are invalid and of no effect.

By this answer we are relieved of any necessity to examine the details of the invention, or to compare the two inventions of Webb and Mallory, to ascertain whether, if the patent held by the complainants be a valid patent, the defendants are infringers. The answer admits that they are using the invention for which the letters were granted to Webb, and their defence is an attempted justification of that use. We may, therefore, confine ourselves to the consideration of the justification thus set up by the defendants.

Some account of the improvement which constitutes the invention claimed may be necessary to make certain points urged upon our attention intelligible. Locks and latches were formerly made so permanently constructed and arranged that they could be used upon one edge of a door only. The catch or bolt of the latch being bevelled on one side, a latch that could be applied to a right hand door could not be used on a left hand door. Separate locks and latches must, therefore, be made, and purchasers must, before buying, assure themselves upon which edge or side of their doors the hinges would be placed. In practice this was found inconvenient, and mistakes were made in purchasing, or changes in the course of erecting houses, in the precise arrangement of doors, or in the swing thereof, gave great trouble. It was, therefore, very desirable to have locks and latches so constructed that the latch or bevelled catch could be readily, by a slight change of adjustment, reversed, whereby, whatever lock and latch was purchased, it could, at the option of the purchaser, be applied to the left or to the right hand edge of the door. Later experience also suggested, that, while it was desirable that the latch should be capable of such adjustment or reversal, either before or after the lock was inserted in or attached to the door, it ought not to be so left, when the whole was in complete order for use, that the latch could then be changed or reversed, because this would enable careless or mischievous persons to reverse it, or expose it to reversal by accident.

In general terms, the invention in question consists in enclosing the inner end of the latch, and the arms and hub, by means of which the latch is to be drawn back, in a thin case, so as to preserve their constant due adjustment, and placing that case within the main case of the lock, between, the two plates thereof, so as readily to slide, between studs projecting from the surface of the main plate, a short distance forward and backward. In this condition of the parts, the thumb and finger, being applied to the bevelled end of the latch, readily pulls it forward, and, its inner end being round and fitted to its yoke within the small case by a knob or a swivel joint, it is turned around, and so may be adapted either to a right hand or left hand door. Being turned, it is pushed backward to its proper and permanent position. The insertion 80of the spindle on the ends of which the door knobs are placed, then holds the inner case with the tumbler or hub and yoke, with the latch also, firmly in place.

1. It is earnestly insisted, that the patent granted to Webb, on which alone the complainants rely, is void, upon facts that are not controverted or are clearly established, namely, that locks were common and latches were common, and locks combined with latches were common, long before the alleged invention of Webb, and that his letters patent purport to be for a combination merely; that, conceding that Webb's improved latch was new, he patented simply the combination of, the latch with the lock, which was simply aggregating two things which had distinct and separate operation, each unaffected by the operation, or even the presence, of the other; that, in short, as there was no relation between them in the performance of their several functions, and no reciprocal action, they are not patentable as a combination; and that the complainants' patent is, therefore, void.

It may not be immaterial to observe, that no such defence is intimated in the answer of the defendants. Not only so, the answer itself, in connection with the production of the patent of Mallory, set up in the answer and there insisted upon as valid, impliedly asserts the validity of a parent for the very subject described and claimed to be secured thereby. It is allowing to the defendants very large liberty, to permit them to depart wholly from the ground taken in their answer as a defence, and that, too, when they set up, in their answer, a patent which is liable to the same criticism, and insist upon its validity, notwithstanding it be found that Webb was the first inventor. The claim in the patent to Mallory, set up in the answer, is in these words: “What I do claim as my invention, and new and useful, and desire to secure by letters patent, is the combination of a lock and latch, when the latch-bolt and its operative mechanism are arranged in a case or frame independent of the main case, and constructed so that the latch-bolt may be reversed, substantially as described, without removing the said independent case from the main case.” The claim of the patentee Webb, as will be stated presently, is in very nearly the same, if not in the identical, words. The defendants have not, in their answer, thought proper to raise any question of the validity of such a claim. They assert their own title to the invention, and justify their use thereof upon grounds which import the validity of the claim in Mallory's patent. Now, on this hearing, the argument of the counsel reverses and contradicts the defence which the defendants have set up, under their own oath. The defendants are, for all the purposes of this case, bound by their answer. A departure from the defence therein alleged is not permitted in courts of chancery, where the complainant is entitled to call upon the defendant to answer under oath. The answer thus put in must be deemed and held to disclose the true and only defence which the defendants have to the allegation of the bill, and they are thereby concluded. It is with the issues thereby raised that the court has to deal.

This case itself furnishes an illustration of the propriety of the rule. Let it be supposed that the defendants wholly fail to establish, by proofs, any of the defences set up in the answer, but the court should be of opinion upon the proofs, that the patent to Webb was void upon the grounds now, with great ingenuity and skill, urged by the defendants' counsel, and, for that reason, should decree a dismissal of the bill of complaint. The reasons for the decree, and the arguments urged by counsel, would not appear by the record. The record would indicate, that, upon the issues made by the answer, the defence therein was found and adjudged, when, in truth, the contrary was the fact. The decree would thus purport to establish that Mallory and not Webb, had the prior right, when the court made no such decision. The record would seem to establish what the defendants claim, namely, that the patentee, Webb, was not the prior inventor, or had, by his laches lost his right to his patent, in favor of the defendants, who would thus be left to stand before the world holders of Mallory's patent, affirming its validity to secure to them a monopoly, when, in truth, they had, outside of and contrary to what the record discloses, obtained a decision which was fatal to both patents. In short, the decision would be in conflict with the record.

Nevertheless, in view of what was claimed by counsel for the defendants, of the force and effect of certain other decisions of this court, and their supposed influence upon the validity of Webb's patent, we have deemed it proper to consider the point, and to show that (irrespective of the objection that such defence or claim is a departure from, and inconsistent with, the answer) it has no real foundation.

2. The claim in the specification annexed to the patent of Webb, which is thus attacked, reads as follows: “What I claim, therefore, and desire to secure by letters patent, is—The combination of a lock and latch, when the latch-bolt and its operative mechanism are arranged in a case or frame independent of the main case, and constructed so that the latch-bolt may be reversed, substantially as described, without removing the said independent case from the main case.”

We are not inclined to depart from what was said in Hailes v. Van Wormer [Case No. 5,904], and Sarven v. Hall [Id. 12,309], on the distinction between a patentable combination and a mere aggregation of old elements having no relation to each other, or any reciprocal or co-operative action to produce the result attained. But, claims should be read in connection with the specification itself, and read in the light gained therefrom; and 81it is proper to give such construction to the language employed as expresses the evident intention, if that may be done. It is manifest, from the whole specification and claim, that the inventor here had no idea of claiming a combination of a lock with a latch, as an invention. His specification shows, that the reversible latch, constructed as described, to be used in connection with, and enclosed by, the lock case, was the improvement which he had made. True, as a mere latch, it was immaterial whether the outer case had also within it the lock mechanism or not. Its presence or absence did not affect the operation of the latch, and, equally, the presence or absence of the improved latch did not affect the operation of the lock. Nevertheless, the improved latch was adapted to be used in the case of the lock, and the whole, as an aggregate, is mentioned; and the inventor declares, that, when such a latch as he has described is united with a lock by enclosure within the lock-case, as mentioned, it exhibits his invention. He might, no doubt, have claimed the improved reversible latch enclosed in any outer case. If that latch, in its construction, mode of operation, and arrangement for reversing, was new and useful, it was patentable, and his patent might have been more comprehensive than it now is. His patent is not to be held invalid because he only claims it when used in an outer case, containing also lock mechanism, if, in fact, his improvement was patentable; not even though there is no relation in the operation of the two, and no effect from the combination which either separately would not produce. Nothing in the cases cited forbids an inventor of a new device from taking a patent under a claim narrowed as closely as he sees fit, and, however much narrower than he might have claimed, the patent is valid.

We think, moreover, that the expression, in the claim, “the combination of a lock and latch,” is not to be technically construed. The whole specification shows what the improve-provement was, and that the lock mechanism has no effect upon its operation. The terms used mean just what is meant by “a combined lock and latch,” or “a united lock and latch,” or “a lock and latch,” when indicating a single article of manufacture or use. It is that aggregate structure, when it contains within the main case the special arrangement and mechanism which the inventor describes, that he claims as his invention. In a somewhat analogous view, any machine or structure may be claimed, when it contains a new device or devices which are described by the inventor as improvements. The claim is for the whole, as a whole, when and when only it contains the new devices. In a certain sense, the lock and latch have a relation to each other, the same relation that the frame of a machine has to the devices sustained thereby. Such device may be no more patentable in a frame of one description rather than another, but, if the patentee chooses to restrict himself to his new device when used in some special connection, he does no wrong to the public and violates no rule of law.

3. On the question of priority of invention, we cannot think it necessary to extend discussion. It is established, we think, by a very large preponderance of evidence. Indeed, there is little contradiction of the three witnesses who testify positively on the subject, two of whom have no interest in the controversy, and are wholly unimpeached. The contradicting witness is the same on whom the defence of abandonment of the invention almost solely depends, of whose credibility we shall have occasion to observe when treating of that subject. We think that no fair mind, weighing the evidence, can doubt that Webb made the invention in, or prior to, March, 1863, and that in that month it was perfected and embodied in a complete lock and latch fitted for use, or that Webb then deemed it a patentable invention, desired and expected to procure a patent therefor, and consulted Mr. Bliss, solicitor of patents, in order to obtain advice as to what was essential to preserve his right to such patent, exhibiting to him, at the time, his completed invention.

4. The remaining ground of the defence is, that the patentee, although the first inventor, by his neglect and his silence, while the defendant Mallory also perfected and put into use and on sale the same invention, is precluded from asserting his claim and has lost his right to the exclusive use of the invention. This ground of defence is exhibited in three forms: First, that Webb abandoned his invention to the public. Kendall v. Winsor, 21 How. [62 U. S.] 322. This, however, is not very strenuously insisted upon, nor is it very distinctly stated in the answer, doubtless, for the reason, that, if this be established, all the public may use it, and the defendants have no exclusive right under the patent of Mallory. The claim involves this concession, and the defendants would not probably seek an adjudication which establishes that Webb was the original and first inventor, but that his invention had, by his voluntary act, become public property. Consideration of the proofs will, nevertheless, include this point, as well as the next, namely—Second, that Webb voluntarily abandoned the invention as useless; that, although his experiment proceeded so far as, in fact, to produce the device or structure, yet he deemed it of no value, or, at least, so treated it, and, by his conduct, placed it upon the footing of an abandoned experiment; and that, therefore, it in no wise stood in the way of Mallory, who himself made the same invention, procured a patent therefor, and put it into public use and on sale, so that the public derived the benefit of the use of the invention. Thus viewed, the case is supposed to-come within the rule held in Gayler v. Wilder, 10 How. [51 U. S.] 477. And third, that the neglect of Webb to apply for a patent, and his silence while Mallory perfected his invention and put it into public use and on sale, 82and sold it extensively, ought, in equity, to estop Webb and the complainants, his assignees, from asserting the priority of the invention, and claiming the exclusive right which a valid patent would secure to them.

It appears, by the proofs, that the invention of Webb was complete, and actually embodied in a practical lock and latch, as early as the last week in March, 1863. His application for a patent was made on the 21st of March, 1865. This is the interval, and the only interval, of time within which the conduct of Webb is to be considered with reference to either of the above propositions included in this branch of the defence. The question of abandonment, in either view above suggested, is a question of fact, and to be determined by the evidence. Lapse of time does not, per se, constitute abandonment. It may be a circumstance to be considered. The circumstances of the case, other than mere lapse of time, almost always give complexion to delay, and either excuse it or give it conclusive effect. The statute has made contemporaneous public use, with the consent and allowance of the inventor, a bar, when it exceeds two years. But, in the absence of that, and of any other colorable circumstances, we know of no mere period of delay which ought, per se, to deprive an inventor of his patent.

As it respects abandonment to the public, the argument that such was the intention of the inventor would have been much stronger, if, after perfecting his invention, he had proceeded publicly to make and sell the same, and voluntarily placed it in public use, accessible and available to any who chose to buy and use, for nearly two years before he made any application for a patent. The argument here pressed upon us, that Webb did not intend to secure any exclusive right, or did not esteem the right of any value, or that he abandoned such right to the public, would, in such case, have been impressive; and yet the express terms of the statute secure to the inventor this interval, in which he may, if he please, test the usefulness and the value of his invention, by putting it into use and on sale, without being thereby barred of his patent, and it necessarily follows, that, from the mere lapse of the period mentioned, no inference of abandonment arises.

If the matter be brought to the test of actual design and purpose, either to abandon the invention to the public, or to cast it aside as a useless invention or unsuccessful experiment, the proof seems to us to establish very clearly the contrary. Webb's continuous or repeated declarations, testified to by himself and by the solicitor of patents to whom he applied for advice, his claim to priority of invention when he heard that Mallory was manufacturing a similar lock and latch, his offers to sell his invention to others, indicate, that, in his mind, there was no purpose to forego the right which belonged to him as inventor, nor any conclusion that the invention should be abandoned. The purpose declared by him to the solicitor of patents, when he had first perfected his latch, he never relinquished. It is, no doubt, true, that, although receiving but a moderate salary for the support of himself and family, he could easily have procured means to pay the expense of taking out a patent. His sale of the patent for a second invention would have enabled him to do this, as he is not shown to have been in debt. But, it is plain what his purpose was, in delaying his application. He did not propose to himself engage in business as a manufacturer. He had not means for such an undertaking. The profits of his ingenuity he expected to realize by negotiation with others who were or should become manufacturers. His delay was, therefore, that he might, perchance, find some one to purchase, or might test the utility and value of his invention by submitting it to the appreciation of those who, being engaged in the manufacture and sale of locks, could better judge of its value than he could himself.

We find no reason for concluding that, when, by express enactment, an inventor may have two years of trial in the public markets, putting his invention in use and on sale, and yet be entitled to a patent, he may not, also, have the like period, at least, within which to offer his right as inventor to others, submit the invention to that test of its usefulness and value, and still be entitled to his patent. The lapse of two years is not the test of his right in this respect, nor is the lapse of any specified period conclusive. The law does not declare within what period after the invention a patent must be applied for, or that it must be applied for within any specified time. We do not mean, that an abandonment to the public may not be made, or that an invention may not be given up and abandoned, as a useless or unsuccessful experiment, within less than two years. No particular time is necessary, but the fact must be proved, and the lapse of two years does not establish it. There may be sufficient reasons why a delay of a much greater number of years will not so operate. On the question of abandonment, in either aspect, time and circumstances, the acts and contemporaneous declarations of the party, are all to be considered.

We have here the positive testimony of the inventor. We have his declarations to others. We have his taking advice on the effect of delay. We have his effort to recover his model or original of his invention, and his final sale of his right as inventor. Laying out of view, for the moment, the testimony of a single witness, there is no act or declaration of the inventor, down to the application for the patent, which is not in harmony with, or which does not confirm, the unequivocal testimony, that there was at no time any design or purpose to forego his right as the inventor of the lock and latch in question. Of that witness we observe, that his testimony tends strongly to show that Webb abandoned this invention as a thing of no value, took to 83pieces the lock he bad constructed in conformity with it, addressed himself to the construction or invention of some other device to accomplish the desired result, satisfied that what he had before done failed to accomplish it in a useful manner, used the parts of his first constructed lock in and toward his further and second invention, left such of the parts as could not be adapted to such second Invention to go to waste as rubbish, and thenceforward entertained no idea of using or patenting such first invention, until he learned that Mallory had brought the same invention into use and put it upon sale. This witness is contradicted in all the material parts of this statement, and in the inference sought to be drawn therefrom, by more than three witnesses, none of whom are impeached otherwise than by his contradiction. True, Webb left the newly-invented lock and latch in the shop of Parkers & Whipple, where he was employed when he invented it. He declares that it was so left by oversight or forgetfulness at the time of his removal; and three persons testify to the distinct declarations of the witness above referred to—one of the proprietors of the shop, John A. Parker—that long afterwards he had that lock and latch in his possession, and two of them testify to his refusal to give it up. These declarations were made on several occasions, and, as to two of the persons, (Webb and an officer of the plaintiffs), on their separate personal application to him for the lock, at about the time when a patent was to be applied for. On the question of the time when the lock was invented, he is, in like manner, contradicted by three witnesses, who are clear and distinct in their testimony. We do not think it necessary to indulge in conjecture as to the motive of this witness to misrepresent, or to consider whether it be possible that he has persuaded himself that what he testified was true, or whether by any means he has been led into a mistaken belief as to the facts. It is sufficient, that, upon the testimony in conflict with his statement, we are constrained to say that it would be wholly unsafe and improper to rest any conclusion in this case upon what he testified.

It follows, we think, that the proofs wholly repel any idea of abandonment of this invention by the inventor, in either sense claimed by the defendants, and show, on the contrary, a continuous claim to be the first inventor, a purpose to secure a patent for the invention, and some appreciation of its usefulness and value, though, no doubt, according to the results now shown, that appreciation was greatly inadequate.

Much that has been already said is pertinent to the third claim above stated, to wit, that, by withholding his application for a patent, and by his silence, not putting his invention into actual public use for nearly two years prior to such application, Mallory meanwhile having made the same invention, and put the same on sale, Webb and his assignees are estopped. Permission to put an invention in public use for two years prior to the application, does not make it the duty of the inventor to do so for that or any other period before he applies. Prior to the act of March 3, 1839 (5 Stat. 354, § 7), such public use, with the consent and allowance of the inventor, destroyed his right to a patent. That act relieves the inventor from the danger of such a forfeiture, and that is all. The question of estoppel, now urged, stands, therefore, upon the same footing as if that act had not been passed. Is it, then, true, that an inventor, who makes no secret of his invention, cherishes and declares his purpose to procure a patent therefor, exhibits it to those who, being engaged in manufacturing articles of a similar kind, are competent to judge of its value, in the hope that they may be disposed to purchase, he himself being in no situation, and having no means, to engage in manufacturing—is an inventor, we ask, in these circumstances, estopped to assert a right to the invention, and to claim a patent, because his application is not made until nearly two years have elapsed? Here was no bad faith, no voluntary acquiescence in the manufacture and sale by others. For, the proof shows, that, when he learned that Mallory was making and selling the same lock and latch, he asserted his prior right, and, in a reasonable time thereafter, applied for the patent. The provision of the law of July 4, 1836 (5 Stat. 119, § 6), which made public use and sale no impediment to the granting of a patent, and no defence to an infringer, unless it was by the consent and allowance of the inventor, shows that such facts create no estoppel invalidating his patent when granted. Apart from the question of abandonment, the mere fact that, prior to the application for the patent, some one has obtained knowledge of the invention, and placed the thing invented on sale, whether innocently or fraudulently, does not cut off the prior right. True, the patentee cannot claim damages or profits arising before his patent is granted or applied for; but, he comes to these defendants now, as he would to any party who, in ignorance, in fact, of the existence of any patent, had engaged in the manufacture, and says: “From and after the date of my patent you were bound to take notice of my rights. They were claimed, and my claim was of record in the patent office. Thenceforward, the manufacture of the patented lock and latch was an infringement of my rights. For what you had done before, you are not and cannot be pursued, but then you were bound to refrain from further manufacture.” No equity beyond this can be urged in favor of such prior manufacturer; and the circumstance that he was also, in fact, an original inventor, and believed himself to be the first inventor, does not affect the question. He is in no better situation than one who ignorantly and innocently supposed that the invention was open to the public. These considerations lead us 84to conclude that the complainants are entitled to the decree prayed for in their bill.

[For another case involving this patent, see Russell & Erwin Manuf'g Co. v. Corbin, Case No. 12,167.]

1 [Reported by Hon. Samuel Blatchford, District Judge, and by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here compiled and reprinted by permission. The syllabus and opinion are from 10 Blatchf, 140, and the statement is from 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 632. Merw. Pat. Inv. 439, contains only a partial report.]

2 [From 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 632.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.