Case No. 11,925.

20FED.CAS.—60

ROBERTSON v. HILL.

[6 Fish. Pat. Cas. 465;1 4 O. G. 132.]

Circuit Court, D. Massachusetts.

Aug., 1873.

PATENTS—COMBINATION—ADDITION OF NEW ELEMENT TO MAKE USEFUL—PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION—WHAT CONSIDERED—HAND-STAMPS.

1. When the validity of a patent has been fully established in prior cases, on a motion for a preliminary injunction, the court will seldom hear any evidence except on the question of infringement.

[Cited in American Bell Tel. Co. v. National Improved Tel. Co., 27 Fed. 665; Edison Electric Light Co. v. Beacon Vacuum Pump & Electrical Co., 54 Fed. 679.]

2. Under such circumstances, the party, by the established rules of equity, is entitled, as a matter of course, to a preliminary injunction, without a trial at law.

3. This is especially true when the party defendant was interested in the defense of the prior cases.

4. It is the established rule of court, in such a case, on a motion for injunction, to consider only the question of infringement.

[Cited in Tillinghast v. Hicks, 13 Fed. 391.]

5. When a party has patented a combination, and the combination turns out to be useless, and another party adds to the combination another element, and thereby makes the whole practically useful, the party who adds this last element is not an infringer, and he is entitled to use, not merely his improvements—requiring first a license to use the former combination-but he may use the whole of it.

6. Complainant having patented the combination of a handle and a series of printing-wheels, for printing dates, with a fixed type form, and printing-die, for dating purposes, and the use of a ribbon as an inking device being old in other combinations, defendant is not entitled to use complainant's combination in connection with this inking device, as complainant was himself entitled, in the use of his combination, to avail himself of any device well known at the date of his patent.

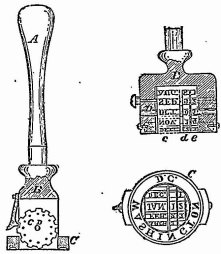

In equity. Motion for preliminary injunction. Suit brought [by Thomas J. W. Robertson against Benjamin B. Hill] on letters patent for “improvement in hand-stamps,” granted to Thomas J. W. Robertson, September 22, 1857 [No. 18,249]; extended and reissued December 12, 1871 [No. 4,675]. The claims of the patent were: “1. In combination with a handle and a series of printing-wheels, or their equivalents, for printing dates, a fixed type form or printing-die, for dating purposes, substantially as described. 2. A hand-stamp, having a permanent inscription, form, or die, provided with an aperture, through which the type-wheels work, when so arranged that the said type-wheels may be turned for changing the dates without shifting the fixed form or die, substantially as specified. 3. A hand-stamp, having a series of type-wheels, provided with holes, to receive a locking-pin, E, substantially as specified.”

The claims, with the engravings, show fully the nature of the invention.

945

The patent had been previously sustained in the cases of Robertson v. Secombe Manuf'g Co. [Case No. 11,928], and Robertson v. Garrett [Id. 11,924], where will be found a more extended description of the invention. The motion was resisted on the ground that the invention was anticipated by a large number of English and French patents, and because the invention, as patented, was lacking in utility, from the absence of any suitable device for inking the face of the stamp; and that the defendant, having combined the complainant's combination with an inking device, which made the whole combination useful, could not properly be held as an infringer.

Frederic H. Betts, for complainant.

James B. Robb, for defendant.

SHEPLEY, Circuit Judge. This is a motion for a preliminary injunction. In this case, the patent has frequently been made the subject of legal investigation.

The validity of the patent has been established and confirmed in at least three cases, and under such circumstances, on a motion for a preliminary injunction, the court very seldom hears any evidence, except on the question of infringement. Under such circumstances, the party, by the established rules of equity, is entitled, as a matter of course, to the preliminary injunction without a trial at law and without further trial of the cause, especially in a case like this, where the party defendant in the cause was interested in the defense of the suit, and had full opportunity to test the question.

Ordinarily, therefore, in such a case, the court, on a motion for a preliminary injunction, considers only the question of infringement, and that is the established rule of the court.

In this case, however, the court has considered, with as much care as the time would allow, one question which has been raised by the counsel for the defendant, and which, may properly be considered under the question of infringement It is contended by the defendant that when a party has patented a combination, and that combination turns out to be useless, of no practical utility, and another party adds to that combination another element, and thereby makes the whole practically useful where there was no utility before, the party who thus adds another element to the combination, which was necessary to make the prior combination of any practical utility, is not an infringer, and that he is not entitled merely to use his improvements, requiring first a license to use the former combination, but that he may use the whole of it; and that view of the law is undoubtedly correct.

In that view of the law, it is contended that there is no infringement in this case, and it is with a view to the question of infringement only that the court has considered it not deeming it necessary to go into any consideration of the question of novelty, or entertain or express any opinion on that question until the final hearing of the cause.

But considering that the right of the party depends upon the validity of the patent, and! the fact that that question has been adjudicated so many times, it is not the intention of the court, in any case, upon a motion for a preliminary injunction, to express any further opinion upon the questions involved in the case, except such as are absolutely necessary to the decision of the question of infringement on the motion for a preliminary injunction.

But on an examination of the patent, the court, while it believes that view of the law to be correct, can not conceive it to be applicable to the present case.

It is contended by the defendant in this case that the combination of the plaintiff, which was the combination of a handle and a series of printing-wheels, or their equivalents, for printing dates with a fixed type-form or printing-die for dating purposes, substantially as described, had no practical utility, because without the inking ribbon or device which the defendant has added, it was of no practical use; that the wheels would: clog by the, ink; and it was of no practical use, and did not come into use, until the ribbon as an inking device was added to it by the defendant.

But it does not appear that Robertson, the patentee, here, has stated in his patent any combination with any inking device, but has stated that his combination could be used with any suitable inking device.

An inking device formed no part of his combination, but it could be used, he says, with any suitable inking device. Now, the testimony in the case shows very clearly that the ribbon was an inking device, which was known prior to the date of this patent—was known and in use, and described in patents prior to the date of this patent. It was, 946therefore, one of the inking devices which the complainant had a right to use, and which he is to he considered, in the eye of the law, as having referred to as a suitable inking device in his patent.

Therefore, although it should be proved to be true, that if the plaintiff's combination were used with a common inking-pad, or by applying printer's ink with rollers in the usual way, it would so clog and interfere with the turning of the wheels that it would not be a practically useful device; still he was open to use the ribbon as a roller, which had been known and used as an inking device prior to the date of the patent.

The conclusion of the court, therefore, is, that under the present state of the proof, in view of the prior decisions in the case, the injunction must go, as prayed for.

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here reprinted by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.