Case No. 11,757.

RICH v. CLOSE.

[4 Fish. Pat. Cas. 279; 8 Blatchf. 41.]1

Circuit Court, N. D. New York.

Oct., 1870.

PATENTS—CLAIMS—COMBINATION—IN AGGREGATE—OMITTING IMMATERIAL PARTS—EQUIVALENTS—WATER WHEELS.

1. An inventor must be taken to know of what his invention consists, and his patent does not secure to him the exclusive right in any thing more than he claims to have invented.

[Cited in Rowell v. Lindsay, 6 Fed. 293.]

2. Although it is true that in the construction of a claim, reference may be had to the specification to ascertain the true interpretation of the claim, yet, where the claim is such as to leave no room for construction, where it is clear and explicit, and especially, where there is nothing in the specification which shows that the patentee did not mean just what the plain language of the claim imports, the court is not aided by, and has no need of aid from, such specification.

3. When a machine is patented as an aggregate, third parties may not deny an infringement on the ground that they omit immaterial parts, or use fewer of the original old elements, or substitute equivalents.

[Cited in Coolidge v. McCone, Case No. 3,186.]

4. The letters patent granted to Reuben Rich, July 8, 1842, for an “improvement in water-wheels,” wherein the patentee claims only “the combination of the wheel, constructed as hereinbefore described, with the spiral conductor D, and tube F, so as to get the full pressure of the water, while the wheel is relieved of its weight, in the manner and for the purpose set forth,” is not infringed by a combination of the wheel with the spiral conductor alone, without the tube or any equivalent therefor.

[Cited in Rowell v. Lindsay, 6 Fed. 293.]

5. The use of the wheel and the spiral conductor in combination, in such location, in reference to the flume, as to render the tube unnecessary, is not the substitution for the tube of an equivalent therefor, and is no infringement of such claim.

6. A patent for a mere combination of three distinct devices is not infringed by the use of only two of such devices, without the other.

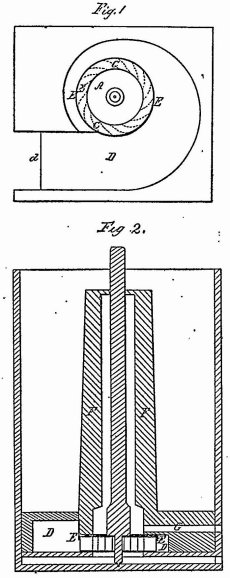

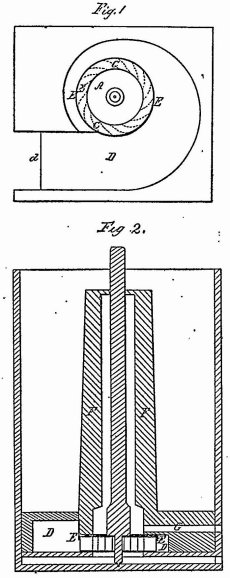

This was an action on the case [by Julia Rich, administratrix, against Beroth Close] for the infringement of letters patent [No. 2,708] granted to Reuben Rich, July 8th, 1812, for an “improvement in water-wheels.” The specification called the improvement the “pressure center-vent water-wheal.” The specification said: “The nature of my invention consists in receiving the water on the wheel at its periphery, from the flume, by a spiral conductor, and discharging it as soon as it passes the buckets, thus giving the full action of the water, and relieving the wheel of its weight, as soon as it passes that point. The wheel, formed of iron or other suitable substance, when running horizontal, has its upper face formed of a flat plate, A, just the size of the wheel. Around its outer edge, there is a series of ogee-formed buckets, B, extending downwards at right angles, to its under side, and obliquely to the radii, overlying each other to any distance desired. A ring, C, is attached to the lower edge of these buckets, which is wide enough to reach from their outer to their inner edge, and leave the centre open for the free egress of the water. The vertical shaft passes through the centre of the top plate, A, and is firmly attached thereto. The wheel, so constructed, is surrounded by the spiral conductor D, to convey the water from the flume on to it. The space between this conductor and the wheel gradually contracting in width and height, from the entrance at d, around the whole circumference of the wheel, has a tendency to press the water towards the centre. From the top of this conductor, a flange, E, projects down around the wheel, as close as possible without touching, the thickness of the upper plate, and prevents the water from running in over the wheel. A tube, F, surrounds the shaft, extending up above the water line; and, in the side of this tube, just 671over the wheel, there is an aperture, G, which opens outside of the flume, for conducting off any water which may leak in over the wheel, and thus prevents its becoming clogged. Operation. When the water is let on to this wheel, the spiral serves to create an equal pressure towards the centre of the wheel on all sides, and, acting on the buckets while passing through them, relieves the wheel of its weight, as soon as it passes the inner edge of the ring C, falling down and passing off freely from the centre.” The claim was as follows: “What I claim as my invention, and desire to secure by letters patent, is, the combination of the wheel, constructed as herein before described, with the spiral conductor D, and tube F, so as to get the full pressure of the water, while the wheel is relieved of its weight, in the manner and for the purpose set forth.”

[Drawings of patent No. 2,708, granted July 8; 1842, to B. Rich: published from the records of the United States patent office:]

At the trial, it appeared, that, in the defendant's wheel, the water was received on the wheel at its periphery, from the flume, by a spiral conductor, which was outside of the flume, and received the water from the flume through an aperture in the side thereof, and was attached to the flume, so that the tube F was dispensed with. The plaintiff offered to prove, that the tube F was not necessary to the successful working of the plaintiff's combination, but the evidence was excluded. The court held that the plaintiff could not recover unless the defendant used, as an element of the combination, the tube P. The defendant had a verdict, and the plaintiff now moved for a new trial, on a case.

Alexander H. Ayers, for plaintiff.

John M. Carroll, for defendant.

WOODRUFF, Circuit Judge. There is some reason to apprehend that the patentee, in this case, failed to secure to himself all that he might have secured, if he had not restricted his claim, as the inventor, to a mere combination. The argument of the plaintiff's counsel assumes, that the combination of a spiral conductor with a water wheel open at the bottom, through which the water would fall freely after passing through ogee buckets constructed as described in the specification annexed to the patent, was his invention; and this assumption does find some color in the language of the specification. But the patentee made no such claim in fact. It is perfectly consistent with the specification, and with the plaintiff's claim, to assume: (1) That the water-wheel described was not new; (2) that the spiral conductor was not new; (3) that the use of a tube, F, above a water-wheel, to remove water which, being thereon, would impede its revolutions, was not new; (4) that the use of the spiral conductor described, to conduct water to the periphery of just such a wheel, and cast it against the buckets, was already common. The patentee may have invented each, but he has not said so, and he has not claimed that he did.

An inventor must be taken to know of what his invention consists, and his patent does not secure to him the exclusive right in anything more than he claims to have invented. If his specification is imperfect, through mistake or inadvertence, the law enables him to obtain a reissue, so as to conform to the truth in this respect

Here, the patentee has narrowed his claim, by the use of terms which are express and clear: “What I claim as my invention, and desire to secure by letters patent, is, the combination of the wheel, constructed as herein before described, with the spiral conductor D, and tube F, so as to get the full pressure of the water, while the wheel is relieved of its 672weight, in the manner and for the purpose set forth.” He does not claim to have invented either of the parts separately, nor to have invented a useful combination of any two of the parts without the third. He may have invented each of them, but he has not obtained a patent for either of them. We are, therefore, left to the assumption, that each was old, and that his specific combination alone was new.

It is quite true, that, in the construction of a claim, reference is to be had to the descriptive portion of the specification, or to any other portion of it, to ascertain the true interpretation of the claim. But, where the claim is such as to leave no room for construction, where it is clear and explicit, and, especially, where there is nothing in the specification which shows that the patentee did not mean just what the plain language of the claim imports, we are not aided by, and have no need of aid from, such specification.

The case, therefore, stands thus: The patentee has not claimed to have invented the wheel described, or the combination of the wheel with the spiral conductor, and has not obtained a patent for either. He, therefore, has no exclusive light by virtue of which he could prevent the defendant's using either.

It is true, that inventions in general involve combinations of old devices. No machine is made that does not, in various of its parts, require, for its construction, the use of what is known and open to the use of all the world. Hence, when a machine is patented as an aggregate, third parties may not deny an infringement on the ground that they omit immaterial parts, or use fewer of the original old elements, or substitute equivalents. The question will still recur—Is the alleged infringement substantially the same machine?

But, here, the patentee claims to combine a wheel and a spiral conductor, neither of which he claims to have invented, with a tube, F, to carry off the water from the surface of the wheel. Now, if the defendant had substituted an equivalent device for the tube F, he might be an infringer. But he was not, by this patent, prevented from using the other two without any such device. His using them in a location, in reference to the flume, which rendered the tube unnecessary and useless, was not substituting an equivalent device, but was only using them without any device of any kind for the purpose indicated. The case falls, therefore, within the rule stated, namely, that, when a combination of known elements or devices is patented, and the combination only, the use of any of the devices less than all is no infringement This rule is not to be construed so strictly as to conflict with the other rule above stated, and to permit the substitution of equivalent devices, where the combination is substantially the same. But, here, the tube F is a distinct member of the combination, for a specific useful purpose; and it cannot be rejected in determining what is, in law and in fact, the subject of the patent.

If the wheel had been claimed, or the combination of the wheel and the spiral conductor, the defendant could not have protected himself by dispensing with the tube F, although the plaintiff had also patented the three in combination; but, as the case stands, I see no alternative but to hold the ruling on the trial correct.

The motion for a new trial is denied.

1 [Reported by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and by Hon. Samuel Blatchford, District Judge, and here compiled and reprinted by permission. The syllabus and opinion are from 4 Fish. Pat. Cas. 279, and the statement is from 8 Blatchf. 41.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.