Case No. 8,724.

McCORMICK v. MANNY et al.

[6 McLean, 539;1 4 Am. Law Reg. 277; 61 Jour. Fr. Inst. 176.]

Circuit Court, N. D. Illinois.

Jan. 16, 1856.2

PATENTS—REAPING MACHINE—EXPIRATION—DISTINCT PARTS—COMBINATIONS—IMPROVEMENT—MECHANICAL EQUIVALENT.

1. The plaintiff's first patent for a reaping machine being dated in 1834 has expired, and whatever invention it contained now belongs to the public.

2. Improvements were made by McCormick, for which, in 1845, he obtained a patent, and in 1847 a patent for a further improvement, which last patent was surrendered and re-issued in 1853.

3. A machine may consist of distinct parts, and some or all these parts may be claimed as combinations. In such an invention, no part of it is infringed, unless the entire combination or the part claimed shall have been pirated.

[Cited in Silsby v. Foote, 20 How. (61 U. S.) 392.]

4. In his patent of 1845, for improvements in the reaping machine, the plaintiff claimed the combination of the bow L, and dividing iron M, for separating the wheat to be cut from that which is left standing, and to press the grain on the cutting sickles and the reel. The defendant's wooden divider does not infringe that claim of complainant's patent which embraces the combination of the bow and the dividing iron, as he does not use the iron divider which the plaintiff combined with the wooden.

5. Where the plaintiff's patent calls for a reel post, set nine inches behind the cutters, which is extended forward, and connected with the tongue of the machine to which the horses are geared, it is not infringed by a reel bearer extending from the hind part of the machine and sustained by one or more braces. The only thing common to both devices is supporting the end of the reel nearest to the standing grain. In their combinations and connections, and in everything else the devices are different.

6. Where reaping machines, prior to the plaintiff's invention, had a grain divider or reel post similar to the plaintiff's, the defendants may use the same without infringing the plaintiff's patent.

7. The invention embraced in plaintiff's patents of 1847 and 1853, was not a raker's seat, but it was the improvement of his machine, by which it was balanced, and the shortening of the reel so that room was made for the raker's seat on the extended finger-bar. This being his invention and claim, to this his exclusive right is limited. Had he claimed generally a seat for the raker, the claim would have been invalid, by reason of the prior knowledge and use of raker's seats in reaping machines. McCormick's raker's seat was new in its connection with his machine; but his invention did not extend to a raker's seat differently arranged.

8. A mechanical equivalent is limited to the principle called for in the patent, including colorable alterations, or such as are merely changes as to form.

9. Manny's reaping machine does not infringe either of McCormick's patents. The divider and reel bearer used in Manny's machine being different in form and principle, do not infringe McCormick's patent of 1845.2

131510. The stand or position for the forker, invented and patented by John H. Manny, is a new and useful improvement, and different in form and principle from McCormick's patents of 1847 and 1853.

[Cited in Hoffheins v. Brandt, Case No. 6,575.]

This was a bill in chancery filed in the circuit court of the United States for the northern district of Illinois, by Cyrus H. McCormick against John H. Manny and others, charging them with infringement of his patents for improvements in the reaping machine, dated January 31st, 1845 [No. 3,895], October 23d, 1848 [No. 5,335], re-issued May 24, 1853 [No. 239]. The defendants filed their answer, setting up various grounds of defence, but relying chiefly on the defence that the reaping machines manufactured and sold by them at Rockford, Illinois, under the name of Manny's Reaper, differ in form and principle from the improvements patented by McCormick, and that the raker's stand or position was an improvement invented and patented by John H. Manny. Issue being joined, a large volume of testimony was taken, showing the state of the art of making reaping machines before and after the date of McCormick's patents. The cause standing for hearing on the bill, answer, exhibits and testimony, it was by agreement of counsel heard at Cincinnati, in September 1855, before the Honorable John McLean, circuit judge, and the Honorable Thomas Drummond, district judge of the United States for the Northern district of Illinois.

Reverdy Johnson and E. N. Dickerson, for complainant.

Edwin M. Stanton and George Harding, for defendants.

On behalf of the complainant it was submitted that letters patent had been granted to the complainant January 31st, 1845, for improvements in reaping machines. In this patent, among other things, there was described and claimed a device for dividing and separating the grain to be cut, from that which was to be left standing, as the machine passed around the grain field. And also a device to suppport the end of the reel on the side nearest to the standing grain, so that the cut grain could be brought freely on the platform of the machine. Another patent was granted to the complainant, October 23d, 1847, and re-issued to him, on an amended specification, May 24th, 1853. This patent specified and claimed an improvement for supporting the raker's body on the machine, while he raked off the cut grain and deposited it in gavels on the ground at the side of the machine. It was contended that the defendants had made and sold for the harvest of 1854, eleven hundred reaping machines, and for the harvest of 1855, three thousand reaping machines, in all of which there were devices for dividing and separating the grain, for bearing up the reel and devices for supporting the raker, substantially the same as were specified and claimed by the complainant. A decree of a perpetual injunction and an account of profits were asked for.

On behalf of the defendants it was submited, that prior to the date of complainant's Inventions and patents, various devices for dividing and separating grain had been described, patented, or used, and on this point especial reference was made to the machines of Dubbs, Cummings, Bell, Phillips, Duncan, Randall, Schnebly, Hussey, Ambler, and others. That anterior to the same date, reaping machines, containing devices for bearing up the reel out of the way of the cut grain, had been described, patented or used, by Cummings, Bell, Ten Eyck, Phillips, Duncan, Schnebly, and Randall. And that prior to McCormick's invention, devices for supporting the raker's body had been used in the machines of Hussey, Randall, Schnebly, Woodward, Nicholson and Hite. Defendants' counsel contended that McCormick's patents of 1845, 1847, and 1853, on their face, purport to be for special improvements in the machine patented by him in 1834, and not for the discovery of any new principle, method, or combination for reaping, in general. His exclusive right is, therefore, limited to the specific improvements he invented, described, and claimed in his patent The patents for these improvements are to be construed in reference to the general state of the art, to McCormick's prior inventions, and to the particular description of his improvements, and the specification of his claim. And so that, while securing him the exclusive right contemplated by law, at the same time to guard against his withdrawing from the public anything before discovered, known, or used by others, or that was contained in his original patent. For a patentee has no right to extend the term of his monopoly over anything embraced in his original invention, under color of some improvement on it. The claims for the seat, the reel post, and the divider, are efforts to acquire a monopoly of the reaping machine, by enlarging, modifying and changing the description and specification of particular improvements, and expanding them so as to cover principles, methods and results, in violation of the principles and avowed policy of the patent laws. And the result aimed at by the complainant would withdraw from the public the contribution of many minds, and subject an instrument of great public utility to a private monopoly, without even a decent color of right. The merit claimed for McCormick, of being the the first man who brought the reaping machine into successful use, was wholly aside from the present question. For, even if that merit justly belonged to McCormick, it is not the ground on which the patent law confers an exclusive right to the machine. And, besides, it could only extend to his own improvements; whereas, to the principal parts constituting the machine, he has not the shadow of any claim, as inventor. 1316 The opinion of the court was delivered at Washington, on the 16th of January, by Mr. Justice McLEAN, as follows:

MCLEAN, Circuit Justice. This is a bill to restrain an alleged infringement of the plaintiff's patent, by the defendants, and for an account. By consent of the parties, the case was adjourned from Chicago to Cincinnati, at which place it was argued on both sides with surpassing ability and clearness of demonstration. The art involved in the inquiry was traced in a lucid manner, and shown by models and drawings, from its origin to its present state of perfection. And if, in the examination of the cause, the entire scope of the argument shall not be embraced, no inference should be drawn that the court was not deeply impressed with the artistical researches and ingenuity of the counsel.

It is proper that I should say here, that after the close of the argument at Cincinnati, no time was afforded for consultation with my brother judge. At my request he has lately transmitted to me his opinion on the points ruled, without any interchange of views between us, and there is an entire concurrence on every point. Cyrus H. McCormick, a citizen of Virginia, represented to the patent office, that he had “invented a new and useful improvement in the machine for reaping all kinds of small grain,” which improvement was not known or used before his application, on which he obtained a patent, dated 21st of June, 1834. As that patent has expired, and whatever of invention it contained now belongs to the public, no further notice of it in this place is necessary. The same individual, in representing to the patent office, that he had invented certain new and useful improvements on the above machine, obtained a patent for those improvements, dated the 31st of January, 1845.

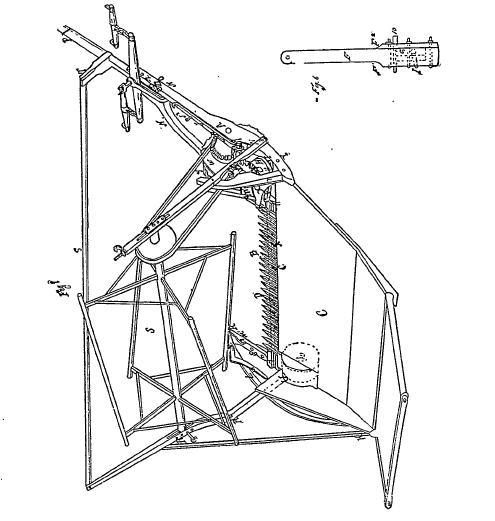

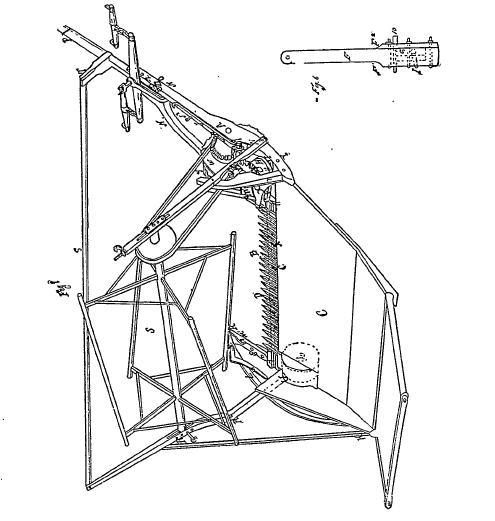

[Drawings of patent No. 3,895, granted January 31, 1845, to C. H. McCormick, published from the records of the United States patent office.]

After describing certain improvements in 1317the cutting apparatus, the divider, and the reel post, he makes the following claim: (1) The curved (or angled downward, for the purpose described,) bearer for supporting the blade in the manner described. (2) The reversed angle of the teeth of the blade, in the manner described. (3) The arrangement and construction of the fingers (or teeth for supporting the grain) so as to form the angular spaces in front of the blade, for the purpose designed. (4) I claim the combination of the bow L and dividing iron M, for separating the wheat in the way described. (5) Setting the lower end of the reel post (R) behind the blade, curving it at R2, and leaning it forward at the top, thereby favoring the cutting, and enabling him to brace it at the top by the front brace (S,) as described, which he claims in combination with the post. And afterwards, McCormick applied for another patent, for improvements made on his reaping machine patented in 1845, and it was issued to him the 23d of October, 1847.

This patent was inoperative, as the patentee afterwards alleged, by reason of a defective specification; and he surrendered it, and obtained a corrected patent the 24th of May, 1853. In his specifications of this patent, he says, “the reaping machines heretofore made may be divided into two classes. The first class having a seat for a raker, who, with a hand rake equal in length to the width of the swath cut, performs the double office of gathering the grain to the cutting apparatus and on to the platform, and then of discharging it from the platform on the ground behind the machine.” The defects of the first class were remedied, he says, by the second class, in which a reel was employed to gather the grain to the cutting apparatus, and deposit it on a platform, from whence it is raked off by an attendant, who deposits the grain on the ground by the side of the machine, where it can lay as long as desired; the whole width of the swath being left unencumbered for the passage of the horses on the return of the machine to cut another swath. And he states that the length of the reel leaves no seat for the raker, who has to walk on the ground at the side of the machine and rake the grain from the platform, and, he says, the weight of the machine is too great, back of the driving wheel. For these defects he has provided a remedy by his improvements, which places the driving wheel back of the gearing that gives motion to the sickle, which is placed in a line behind the axis of the driving wheel and the cog-gearing, which moves the crank forward of the driving wheel, so as to balance the frame of the machine with the raker on it And also in combining with the reel, which deposits the grain on the platform, a seat, or position for the raker to sit or stand, so that he may rake off the grain, thrown upon the platform by the reel, on the side of the machine farthest from the standing grain.

And in conclusion he says: “What I claim as my invention, and desire to secure by letters patent, as improvements on the reaping machines secured to me by letters patent dated the 24th of June, 1834, and the 31st of January, 1845, is placing the gearing and crank forward of the driving wheel for protection from dirt, &c., and thus carrying the driving wheel further back than heretofore, and sufficiently so to balance the rear part of the frame, with the raker thereon; and this position of the parts is combined with the sickle back of the axis of motion of the driving wheel, by means of the vibrating lever, substantially, as herein described.” And he claims “the combination of the reel for gathering the grain to the cutting apparatus, and depositing it on the platform, with the seat or position for the raker, arranged and located as described, or the equivalent thereof, to enable the raker to rake the grain from the platform, and lay it on the ground, at the side of the machine.” The defendants in their answers, deny the validity of the plaintiff's patent for want of novelty, and on other grounds; but in their argument they disclaim any such purpose; and place their defence on a denial of the infringement charged. The infringement of the plaintiff's patent is alleged to consist in his divided reel-post, and its connections, and the raker's seat.

The fourth claim in the plaintiff's patent of 1845, is “the combination of the bow L and dividing iron M, for separating the wheat in the way described.” He describes the divider “as the extension of the frame on the left side of the platform, three feet before the blade, for the purpose of separating the wheat to be cut, from that to be left standing, and that whether tangled or not.” This divider gradually rises from the forward point, with an outward curve or bow, so as to throw off the grain to the left, and thus separate it from the grain to be cut. And this is combined with a dividing iron rod or bar, made fast by a bolt to the timber extended, as a divider, which bolt also fastens the bow. From this bolt the iron rises towards the reel at an angle of thirty degrees, until it approaches near to it, when it is curved to suit the circle of the reel. This iron is adjustable to suit the lowering or elevation of the reel, by a bolt and slot in the lower end. By its gradual rise, this iron divider elevates the tangled grain, and presses it against the cutting sickles of the machine.

There can be no doubt that this combination of the bow and iron divider, as claimed, is new, it not having constituted a part of any reaping machine prior to the complainant's.

In the specifications of the defendant's patent, he says, “the divider F. projects on the left side of the machine in advance of the guard fingers, and divides the grain to be cut from that which is to be left standing, &c., 1318and the machine constructed under his patent has a wooden projection, somewhat in the form of a wedge, extended beyond the cutting sickles some three feet; and which, from the point in front, rises as it approaches the cutting apparatus, with a small curve, so as to raise the leaning grain and bring it within the reel on the inner side of the divider, and on the outer side by the projection, to disentangle the heads and stalks, so as to leave them with the standing grain.” This is not dissimilar in principle from the wooden divider of the plaintiff's machine; the, curve outward may be less, and the elevation from the point which enters the grain may also be less than McCormick's, but it performs the same office, and in principle they may be considered the same, and the question necessarily arises, whether in this respect, this divider is not an infringement of the plaintiff's patent. A satisfactory answer to this inquiry, is not difficult. The plaintiff claims that his wooden divider is in combination with the iron rod on the inner side, which rises from its fastening at an angle of thirty degrees. The adjustability of this iron, by giving it a lower or higher elevation, is also important, and would of itself be a sufficient ground for a patent. But in this inquiry, the adjustability of the iron divider is not important, as it may be considered stationary. A patent, which claims mechanical powers or things in combination, is not infringed by using a part of the combination. To this rule there is no exception. If, therefore, the wooden divider of the defendant's machine, be similar to that of the plaintiff's, there is no infringement; as the combination is not violated in whole but in part. But there is another, and an equally conclusive answer, to the objection. The plaintiff's wooden divider was not new, and therefore, could be claimed only in combination. The English patent of Dobbs in 1814, had dividers of wood or metal. The outer diverging rod of Dobbs' divider rises as it extends back, and at the same time, diverging laterally from the point of the divider, acts the same as the McCormick divider of 1845, to raise stalks of grain inclining inwards, and to turn them off from other parts of the machine.

The English patent of Charles Phillips, in 1841, had a dividing apparatus, consisting of a pointed wedge-formed instrument, which extended same distance in advance of the cutting apparatus and reel; its diverging inner side, like the corresponding side of Mc-Cormick's divider of 1845, bears inward upright grain within the range of the reel and cutting knives; while at the same time, its outer diverging edge, like the outer edge of McCormick's divider, bears off standing grain without the range of the reel. And there is an inclined bar, which, being attached by its front to the lower piece, extends backwards and upwards, until it meets the frame of the machine, at a point above and behind the cutting apparatus. Ambler's machine had aslo a divider, not dissimilar to the defendant's. Bell's machine, made in 1825, had dividers on it to press the grain away from the machine on the outer side, and on the inner side to press it to the cutters. Hussey's machine, too, had a point which projected into the grain, and divided it before the cutting knives; the inside to be cut, the outside to remain with the standing grain. In Schnebly's machine, the grain to be cut was separated from that which was left standing, by a divider projecting on the side of the machine. In the plaintiff's patent of 1834, he says, on the left end of the platform is a wheel of about fifteen inches diameter, set obliquely, bending under the platform to avoid breaking down the stalks, on an angle that may be raised or lowered by two moveable bolts, as the cutting may require, corresponding with the opposite sides. The projection of the frame at this end is made sufficient to bear off the grain from the wheel, and he claims “the method of dividing and keeping separate the grain to be cut from that to be left standing.” This patent having expired, whatever of invention it contained, now belongs to the public, and may be used by any one. The inner line of the projecting divider of the defendant's machine, it is contended, has a gradual rise from the point; which answers the purpose of the iron divider of Mr. McCormick's to crowd the grain on the reel and cutters; but, in this respect, the wooden divider of the defendant's is not materially different from those above referred to, and others in use, before the plaintiff's patent of 1845.

In regard to the divider in the defendant's machine, it is clear, that it cannot be considered as an infringement of the plaintiff's patent. The reel-post, as claimed, with its connections, by the plaintiff, seems not to have been infringed by the defendant. In defendant's machine the end of the reel, next the standing grain, is supported by an adjustable arm, which is nearly level, slightly inclined upwards, and supported by a standard towards the rear of the machine. In McCormick's patent of 1845, the reel-post is set back of the cutter, some nine inches at its foot, rising upwards and projecting forwards, and supported at its top by a brace running to and connected with a standard on the tongue of the machine. The reel-post of the defendant is substantially like the one in Bell's reaping machine, and also the patent granted to James Ten Eyck, in 1825. The reel-support or beam of the latter has not the features of vertical and horizontal adjustability contained in the reel-beam of the defendant's; but it is attached to the machine behind the platform on which the cut grain is received, and it extends forward to hold the reel, and to leave the space beneath it unobstructed.

In his patent of 1834, McCormick placed his reel-post before the cutting apparatus, 1319standing perpendicularly, and being braced as described. But in the patent of 1845, that post was set nine inches behind the sickles, leaning forward so as to bring the part of it which supported the reel to its former perpendicular, the post still extending forward so as to admit of being braced directly to the tongue of the machine to which the horses are harnessed. This was rendered necessary, as the first post being in advance of the cutter, encountered the fallen grain, which adhered to it, and clogged the machine. The reel-post, so called, in both these machines, were alike, only as bearers of the end of the reel next to the standing grain; but their structures in every other respect are different. McCormick's reel-postserved as a brace to the machine, its foot being mortised into the left sill of the machine, nine inches behind the cutting sickles; its top, leaning forward, was braced to the tongue of the machine. The defendant's reel-post, like that of Bell's, was connected with the hindmost post of the machine, and was sustained by braces, as the reel bearer. In giving strength to the machine it was unlike the plaintiff's, and if this were not so, the defendant's is sustained by similar reel-posts in other machines, prior to McCormick's.

But in addition to these considerations, the plaintiff claims his reel-post in combination with the tongue of the machine, as described. There is no pretence that this combination has been infringed. From the structure of McCormick's reaper, it was impossible to find a seat for the raker, without an adjustment of the machine which should balance it with the weight of the raker behind the driving wheel. For this purpose the gearing and crank were placed further forward, the finger piece was extended, and the reel shortened, so as to make room for the raker, and enable him to discharge the grain at the side of the machine, opposite to the standing grain. This improvement was claimed as a combination of the reel with the seat of the raker.

In his specifications to the patent of 1853, McCormick describes two classes of machines, the first class having a seat for a raker, who, with a hand-rake, having a head equal in length to the width of the swath cut, performs the double purpose of gathering the grain to the cutting apparatus and on to the platform, and then of discharging it from the platform behind the machine. This was defective, principally, he says, because the grain was discharged behind, in the wake of the machine, rendering it necessary to remove the grain before the return of the machine, and he alleges these defects are obviated by his improvement. In the specifications to John H. Manny's patent, of the 6th of March, 1855, he says, after referring to McCormick's, Schnebly's, Woodward's and Hite's machines, in regard to the seats of the rakers, “the improvement of mine consists, in combining with the reel, which gathers the grain to the cutting apparatus, and deposits it on the platform, a seat or position arranged between the inner end of the platform and the end of the machine next the standing grain, for an attendant to sit or stand on, and which gives due support to him while operating a fork to push the cut grain towards the outer end of the platform, where the grain is first compressed against the wing or guard provided for the purpose, and then by a lateral movement of the fork discharged properly on the ground behind the platform, in gavels, ready to be bound into sheaves.” And in the summing up, the defendant, Manny, says: “What I claim is the combination of the reel for gathering the grain to the cutting apparatus and depositing it on the platform, with the stand or position of the forker, arranged and located as described, or the equivalent thereof, to enable the forker to fork the grain from the platform, and deliver and lay it on the ground at the rear of the machine, as described.”

With a few verbal alterations, this claim is the same as made by the plaintiff, with the exception of the seat of the raker, and the place of deposit for the grain. It must be admitted that the combination of the raker's seat with the reel, as claimed by the plaintiff, was new. And a very important question arises, how far this claim extends. Is it limited to the mode of organization specified, or may it be considered as covering the entire platform of the machine, and all combinations of the seat and reel? The reel was not new, nor was a seat on the platform, or connected with the platform, for the raker, new; but the position for the raker, as described by McCormick, was new. Mr. Justice Nelson, in the case of McCormick v. Seymour [Case No. 8,726] in his charge to the jury said, “the seat was the object and result he was seeking to attain, by the improvement which he supposed he had brought out What he invented was the arrangement and combination of machinery which he has described, by which he obtained his seat. That, and not the seat itself, constituted the essence and merit, if any, of the invention.” The reel was advanced in front of the cutters, and shortened, and the driving wheel was put back and the gearing forward, so as to balance the machine with the weight of the raker on the extended finger piece. In this peculiar organization, the improvement of McCormick consisted. It was adapted to no other part of the machine. To place the raker on any other part of the platform or machine of McCormick, than on the extended finger board, would derange its balance, which was so well adjusted by the improvements described. No such change can be made without experiment and invention; consequently, the improvement of the plaintiff, in this respect, is limited to his specification.

In 1844, Hite made a new and useful improvement 1320on McCormick's reaping machine, patented in 1834, by attaching thereto a seat mounted on wheels for a raker to occupy when raking the grain from the platform, on which it is deposited by the reel. And a patent was issued in 1855, for this improvement, although from the evidence, the presumption was that the improvement had gone into public use more than ten years before. William Schnebly at Hagerstown, from 1823 to 1837, constructed reaping machines. At first a revolving apron was used, but this was discontinued, and after the grain had been thrown on the platform by the reel and the proper motion of the machine, he says he sat upon the machine in rear of the platform, sometimes upon the guard board, and sometimes astride a cap or cross beam, suitable for that purpose, and raked off the grain with a three or four pronged fork, from the platform, and deposited it on the ground at the side of the machine. In the specifications of Woodward's machine, patented in 1845, he says, the raker stands upon the platform L, and as the grain is cut and falls upon the platform, he with a fork or rake conveys it to the hinged box, and when a quantity is accumulated therein sufficient, the rear end of the box falls and deposits the wheat on the ground in the form of a gavel. This box was often dispensed with. The raker rode on the machine. In 1844, Nicholson represented that he had made an improvement on a machine for cutting grain, &c., and he says, “the machine is provided with a pair of shafts, L, for the animal to draw by, and a place, A, for the driver to sit on, and a suitable stand for a raker's seat. And as a part of his improvement he claims a mode of depositing the grain in a line out of the track of the horse, as described. In 1853 a patent was issued for this improvement, to the administrator of Nicholson. In Abraham Randall's patent, dated in 1833, the grain was raked off the machine by a raker, who had a seat on the platform. This part of the machine succeeded well. When a sufficient amount of grain was collected on the platform, to make a sheaf, it was raked off the side. The machine was in use several years. The platform of the defendant's machine, is different from that of the plaintiff's. The latter is constructed so that the side next to the reel and the cutting knives, is parallel with them, while Manny's platform is so constructed as to extend back from the cutters in a diagonal form, which brings its hindmost part, through which the grain is discharged, to the right of the swath cut. This leaves the way open for the machine in cutting the next swath. The raker, in this machine, occupies a place behind the running ground wheel at the rear of the divider, with his face quartering to the horses. Whether we look at the structure of the platforms, or the position of the rakers, no two things could be more unlike than the two machines of the plaintiff and defendant. Do they differ in principle, as well as in form? To provide for McCormick's raker the structure of the machine had to be altered materially, by changing the heavy machinery so as to balance it with the weight of the raker on the extended finger board. The reel had also to be shortened. On Manny's machine the raker occupies a place diagonal to that of McCormick's, and at the farthest part of the platform next to the standing grain. He stands not upon the extended finger board, but on the platform, requiring no shortening of the reel, nor balancing of the machine.

From the patents above referred to, it appears that before the last improvement of McCormick, rakers had been placed upon the machine, intended to perform the same office as McCormick's raker. It is no answer to this fact to show that some of these plans were abandoned or superseded by the progress of improvement. They were embodied in patents, and were not only publicly constructed and used, but the models of the machines were deposited in the patent office, and the patents, with their specifications and drawings, were matters of public record.

Now if these various plans of seating a raker on the machine, as called for in other patents prior to that of McCormick's, did not affect the validity of his subsequent patent, it could hardly be contended that his patent excludes all subsequent improvements for a raker's seat. In the case of McCormick v. Seymour [supra], Mr. Justice Nelson argues very properly in saying, “it is insisted on the part of the learned counsel for defendants, that there is nothing new in this, because there is in the machine of Hussey a seat, or what is equivalent, a position for the raker, in which he may stand and rake off the grain. The seat, that is the position on the platform, is, in one sense, undoubtedly common to both. But Hussey's machine has no reel to interfere with the raking, and the grain, instead of being raked from the platform, is pushed from the back part of it. The question is whether the arrangement of the seat, the combination by which the patentee obtains and can use the seat or position, is similar to or substantially like the contrivance in Hussey's machine. That is the point. The mere fact that a seat was used in previous reapers, does not embrace the idea contained in this patent. That view could only be material under the assumed construction given by the learned counsel for the defendants to the patent, that it is for a seat. If that were the thing invented and claimed by the patentee, then the seat of Hussey would be an answer to the claim.” “There is also another point,” says the learned judge, “to which it is proper to call your attention in this connection, and which has been the subject of discussion by the counsel, and that is, that Hussey, in the construction 1321of his machine in Ohio, at a very early day used a reel in connection with his cutter and raker. It is insisted that this use of the reel in connection with a raker, in Hussey's machine, before the discovery of the plaintiff, destroys his claim to originality. In answer to this, it is claimed, on the part of the counsel for this plaintiff, that the contrivance of Hussey into which the reel was introduced, was substantially different from the plaintiff's contrivance. It appears that Hussey's reel, like the reel of the plaintiff, when his first seat was put on in 1845, interfered with the raker, so as to prevent his raking the grain the whole length of the platform. Hence Hussey had an endless apron, by which the grain, when cut, was deposited at the feet of the raker, so that he could shove it off with his rake.”

I have cited largely from the learned judge, not only because the opinion was greatly relied on by the plaintiff's counsel in the argument of this case, but for the reason that the opinion is sound. The reel, it seems, interfered with Hussey's plan, which was obviated by an endless apron. McCormick dispensed with the apron by putting back the driving wheel and placing forward the gearing, &c., so as to balance the machine, which, with the shortening of the reel, completed his improvement. Now if a raker be seated on a different part of the machine, and where he can rake without balancing the machine, and without interruption from the reel, it is a contrivance and an invention substantially different from McCormick's. To seat the raker on Manny's machines does not require the same elements of combination that were essential in McCormick's invention. His invention in procuring a seat for the inker, being new and useful, was unaffected by those which preceded it. But Manny's contrivance required no such modification and combination of the machinery for a raker's seat, as McCormick's; it is substantially different from his. The seat was not the thing invented, but the change of the machinery, to make a place for it. And where the seat may be placed on the platform, or on any part of the machine, which does not require substantially the same invention and improvement as McCormick's, there can be no infringement of his right. In McCormick's claim for the improvements which gave him a seat for the raker, arranged and located as described, he adds, “or the equivalent therefor.” The words of this claim, “or the equivalent therefor,” can not maintain the claim to any other invention, equivalent or equal to the one described. This would be to include all improvements or modifications of the machine, which would make it equal to McCormick's. This part of the claim can not be construed to extend to any improvements which are not substantially the same as those described, and which do not involve the same principle. It embraces all alterations which are merely colorable. Such alterations in a machine afford no ground for a patent.

As stated by Mr. Justice Nelson, the improvement of McCormick consisted, not In the seat for the raker, but in the modification and new combination of parts of his machine, so as to secure a place for a seat. Had a construction of the seat merely, been the invention, that learned judge admitted the prior seat for the raker on Hussey's machine would have nullified the claim.

Having arrived at the result, that there is no infringement of the plaintiff's patent by the defendant, as charged in the bill, it is announced with greater satisfaction, as it in no respect impairs the right of the plaintiff. He is left in full possession of his invention, which has so justly secured to him, at home and in foreign countries, a renown honorable to him and to his country—a renown which can never fade from the memory, so long as the harvest home shall be gathered.

The bill is dismissed at the cost of the complainant.

[NOTE. This cause was taken on appeal by the complainants to tie supreme court, where the decree of the circuit court was affirmed, with costs, by Mr. Justice Grier. A dissenting opinion was filed by Mr. Justice Daniel. 20 How. (61 U. S.) 402.

[For another case involving this patent, see note to McCormick v. Seymour, Case No. 8,726.]

1 [Reported by Hon. John McLean, Circuit Justice.]

2 [Affirmed in 20 How. (61 U. S.) 402.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.