Case No. 8,708.

McCOMB et al. v. BRODIE.

[1 Woods, 153; 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 384; 2 O. G. 117.]1

Circuit Court, D. Louisiana.

March 8, 1872.

PATENTS—THREE INVENTIONS—SUIT ON ONE—SAME PROCESS—ALL THE USES—COTTON TIES—SAME PRINCIPLE.

1. There may be a claim for two inventions in the same patent if they both relate to the same machine or structure; and an action can be sustained for the infringement of either one of these separate inventions when claimed as separate and distinct in their character.

2. Where plaintiff's patent covered three different features of invention, but suit was brought on one claim only, the jury were instructed to consider the ease precisely as if the patent covered that claim alone.

3. The third claim of letters patent for cotton-bale tie, granted Frederic Cook, March 2, 1858, construed to be for the right to use an open slot cut in a buckle, which, without the cut, would be a closed buckle, so as to allow the end of the 1291tie or hoop to be slipped sidewise underneath the bar through which the slot is cut.

4. If a party uses the open slot for passing the end of a cotton-tie sidewise under the slotted bar, it makes no difference whether such end is in the form of a loop or not, if the result attained is, that the end of the tie has been “slipped sidewise through the slot underneath the bar, so as to effect the fastening with greater rapidity than by passing the tie through endwise.”

5. A man can not have two patents for the same process, because for different purposes.

6. When the means, devices, and organization are patented, the patentee is entitled to the exclusive use of this mechanical organization, device, or means, for all the uses and purposes to which it can be applied, without regard to the purposes to which he supposed, originally, it was most applicable.

7. To constitute infringement, the contrivances must be substantially identical, and that is substantially identity which comprehends the application of the principle of the invention.

8. If a party adopts a different mode of carrying the same principle into effect, and the principle admits of different forms, there is an identity of principle though not of mode; and it makes no difference what additions to, or modification of, a patentee's invention a defendant may have made: if he has taken what belongs to the patentee, he has infringed, although, with his improvement, the original machine or device may be much more useful.

9. All modes, however changed in form, but which act on the same principle and effect the same end, are within the patent; otherwise, a patent might be avoided by any one who possessed ordinary mechanical skill.

[Cited in Burke v. Partridge, 58 N. H. 353.]

10. The rule of damages at law is not what the defendant has made, or what he might have made, but it is the loss sustained by the plaintiff by reason of the infringement.

[Cited in Yale Lock Manuf'g Co. v. Sargent, 117 U. S. 536, 6 Sup. Ct. Ct. 943.]

11. If plaintiff was ready to supply the market with his patented goods, and his business was hindered or interfered with by the competition of defendant, plaintiff's damage will be the amount of profit which he has lost by reason of such interference.

[Cited in Bigelow Carpet Co. v. Dobson, 10 Fed. 387.]

12. If a plaintiff neglects to prove that his patented article was stamped, or that he gave to the infringer the notice required by section 38 of act of July 8, 1870 [16 Stat. 203], a jury can not award him more than nominal damages.

[Cited in Dunlap v. Schofield, 152 U. S. 244, 14 Sup. Ct. 578.]

2[Suit brought upon letters patent [No. 19,490] for an “improvement in metallic ties for cotton-bales,” granted to Frederic Cook, March 2, 1858, and assigned to plaintiffs. The defendant, by way of reconvention, under the code of Louisiana, in addition to the denial of infringement, claimed that the plaintiffs were infringing patent for “improvement in cotton-bale ties,” granted to him, March 22, 1859, and reissued April 27, 1869, and prayed judgment for damages against them. The two actions were tried together.

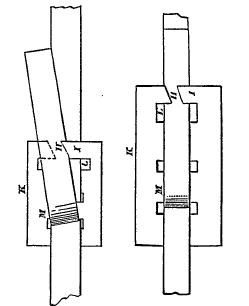

[In the accompanying engravings, K represents the Cook tie, having three slots and four bars. One end of the band was passed ever the first bar on the left, through the first slot, under the second bar, through the second slot, and around the third bar. The end was then brought back under the second bar, and thrust through the first slot and over the first bar. The other end of the hoop having passed around the bale, was thrust under the fourth bar, through the third slot, over the third bar, through the second slot, around the second bar, thence back over the third bar, through the third slot, and under the fourth bar. To avoid the necessity of thrusting the end of the band under the fourth bar, the patentee cut a slit or opening, H, through the fourth bar, I, into the third slot, L, so that the band, when the slack was fully taken up and the end was bent over to form the

final fastening, could be passed sidewise through the opening into the slot and under the fourth bar, so as to effect the fastening with greater facility and rapidity. In the first engraving, the band is represented as passing through this opening; while in the second, it is shown in place. The claim of the patent upon which the whole controversy turned, was as follows: “The herein-described ‘slot’ cut through one bar of clasp, which enables the end of the tie or hoop to be slipped sidewise underneath the bar in clasp, so as to effect the fastening with greater rapidity than by passing the end of the tie through endwise.”

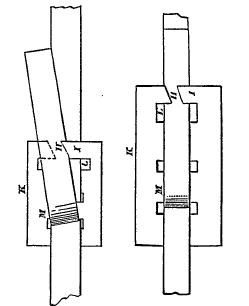

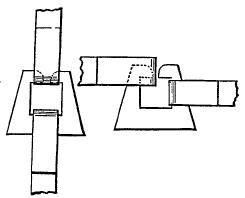

[The accompanying engravings represent the tie made and sold by the defendant. The ends of the band were bent into the form of loops, and slipped through the opening into the slot. The tie was then turned so as to bring the bar through which the slit 1292was cut into the line of draft, the hoop embracing the bar on both sides of the slit, and the ends of the hoop being kept from opening

or slipping by the expansion of the cotton when the bale was released from the press.

[The patent of the defendant contained the following claim: “The connecting link of a bale-tie, having a slit or opening through its side or end, through which the hoop can be introduced into the link, as herein described, and as represented in figures 6, 7, 13, and 14.”

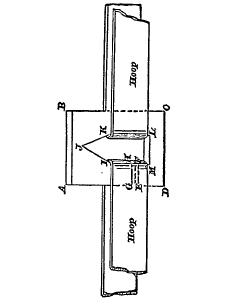

[The “arrow” tie, manufactured and sold by the plaintiffs, and the subject of the suit in reconvention, is illustrated by the above engraving, which gives a bottom view of the tie, with the inserted hooks or ends of the band. The end of the band, by which the fastening is effected, is bent into hook form, and the hooks slipped sidewise through the opening, E, F, G, H, into the triangular space, I, J, K. The strain upon the band causes the loop to slip back into the rectangular portion of the slot, I, K, L, M, and to cover the opening by embracing the bar on each side of it The ends of the band are held by the pressure of the bale, as in the Brodie tie.]2

W. M. Randolph, C. Roselius, F. A. Campbell, and S. S. Fisher, for plaintiffs.

Semmes & Mott, for defendant.

WOODS, Circuit Judge (charging jury). The plaintiffs, Mary Frances McComb and her husband, James Jennings McComb, who sues for himself and to assist his said wife, allege that Frederic Cook, March 2, 1858, obtained from the United States patent office letters patent of that date for an improvement in metallic ties for cotton-bales, issued to him as the original and first inventor; and that said Cook, for a legal consideration, afterwards assigned to the plaintiff, Mary Frances McComb, the full and exclusive right to his said improvement and invention covered by said patent, whereby, under the laws of the state of Louisiana, both the said plaintiffs have the same rights and to the same extent that were granted to said Cook; that they have, since said assignment, and the said Cook before said assignment, and immediately after the issuance of the patent, put upon the market and sold to the public said invention and ties made on the principle described in said patent; and that the defendant, George Brodie, knowing the rights of plaintiffs, and that they were making large profits by the sale of cotton-ties made according to the plan covered by said patent, and with the purpose of invading the rights of said plaintiffs, did, in the year 1868, and after the date of said patent and the assignment, make and use, and vend to others to be used, the invention aforesaid, without license from plaintiffs, or either of them, to the amount of two hundred tons of cotton-ties, to the damage of plaintiffs in the sum of ten thousand dollars.

The answer of defendant to this, the plaintiffs' cause of action, is substantially a denial of the averment that he has in any manner violated the rights of petitioners by the manufacture, use, or sale of ties made on the mechanical principle secured by said letters patent; or that he has at any time made, used, or vended to others to be used, the invention described in the letters patent aforesaid.

The defendant, by way of reconvention, also alleges, that on March 22, 1859, he obtained from the United States patent office letters patent of that date for an improvement in cotton-bale ties, which said letters patent were surrendered April 27, 1869, and, on that date, a patent with amended specifications and claims was reissued to him; and that since April 27, 1869, plaintiffs have infringed on his said invention, by making, using, and vending to others to be used, large numbers 1293of said ties, made according to the plan patented by him, and without his license, to his damage four hundred thousand dollars, for which amount he, assuming the character of plaintiff in reconvention, prays judgment. Under the practice in this state, the denial of plaintiff of the reconventional demand of defendant is presumed, and no formal written denial is required. This abstract of the pleadings presents the issues of fact submitted for your decision.

Your first inquiry will therefore be, has the defendant invaded the rights of the plaintiffs by making, using, or vending, without their permission, the device or contrivance secured to them by the letters patent issued to Cook? To maintain the issue on their part, plaintiffs introduced the letters patent granted to Cook, with the accompanying model, draughts, and schedule, showing the claims of the patentee and the assignment to them of all the rights secured by said letters patent. Whatever invention, therefore, Cook had secured to him by his patent is now the property of plaintiffs. The schedule referred, to in Cook's patent, and making part of the same, and which is in evidence, discloses that the patent was intended to cover three separate and distinct inventions: 1. A friction-buckle or clasp, represented by figures 1, 2, and 3, showing the different views of it, for attaching the ends of iron ties or hoops for fastening cotton-bales or other packages. 2. The manner of looping the ends of the iron ties or hoops into a buckle, by the form of which they are prevented from slipping by friction when the strain of the expansion of the bale comes on the ties. 3. The slot cut through one bar of the clasp or buckle, as shown in the diagram, which enables the end of the tie or hoop to be slipped sidewise underneath the bar in the clasp or buckle, so as to effect the fastening with greater rapidity than by passing the end of the tie through endwise. On this trial plaintiffs say that they complain only of the infringement of the device last above named. Independent things, separable and separate things, where any combination arises, provided they are cognate, relate to the same invention and have relation to the same subject matter, the same object to be accomplished; undoubtedly these separate claims can be made in the same patent, Densmore v. Schofield [Case No. 3,809].

There can be no question that there may be a claim for two inventions in the same patent, if they both relate to the same machine or structure, and an action can be sustained for the infringement of either one or the other of these separate inventions, when claimed as separate and distinct in their character. Lee v. Blandy [Id. 8,182]; Electric Tel. Co. v. Brett, 4 Law & Eq. Rep. 358; Norm. Pat. 108, 109. So the patent of Cook covering, as we have said, three separate and distinct inventions, and these inventions all being cognate and relating to the same subject matter, the plaintiffs may well prosecute for the infringement of any one of them. They have elected to do this in the case on trial, and they only demand damages for the infringement of the last claim set out in the schedule. This claim, as already stated, is for a slot cut through one bar of the buckle or clasp for uniting cotton-ties, which enables the end of the tie or hoop to be slipped sidewise underneath the bar in the clasp or buckle, so as to effect the fastening with greater rapidity than by passing the end of the tie through endwise. You are authorized to consider this case precisely as if Cook's patent covered only the last claim just set out; in other words, as if the patent secured the right to a slot cut through the clasp or buckle for uniting cotton-ties, so as to enable the end of the tie to be slipped sidewise under the bar of the buckle instead of endwise, and nothing else.

The production of the patent is prima facie evidence that the several grants of right contained in it are valid, and that the several things, matters, and devices covered by it were new; that they were useful; that they were the invention of Cook. Potter v. Holland [Case No. 11,330].

It was competent for defendant, by giving thirty days' notice thereof to plaintiffs, to show, if he could, either, first, that the invention had been patented or described in some printed publication prior to Cook's supposed invention; or, second, that Cook was not the original inventor or discoverer of any material or substantial part of the thing patented; or, third, that it had been in public use or on sale in this country for more than two years before his application for a patent, or had been abandoned to the public. Act Cong. July 8, 1870, § 61 [16 Stat. 208]. This notice was not given, and these matters are not at issue; nor is there any denial that the device described in Cook's third or last claim is useful. You may then take it as established that this invention was, when patented, new; that it is useful; that Cook was the first inventor; and that, by assignment, plaintiffs are invested with all the rights of Cook in the patent. In other words, there has been no attempt to overthrow the prima facie case made by the production of the patent and its assignment.

But the question is made, was the device or invention described in Cook's third claim a patentable device or invention? The patent itself is prima facie evidence that it was. A patent can not be granted for a principle or an idea, or for any abstraction whatever; for instance, for the naked idea of a slit, slot, or aperture, disconnected from any application. But when the idea is applied to a material thing, so as to produce a new and useful effect or result, it ceases to be abstract, and becomes a proper subject to be covered by a patent. For instance, the idea of bending the end of a cotton-tie in a particular manner, would not be the subject of a patent; but when the idea is applied 1294to the fastening of the tie to a clasp or buckle, so as to produce a new and useful result, then it becomes patentable. So the abstract idea of a slot in a buckle is not of itself patentable; but when the idea is applied to a buckle, so that the result is new and useful, or so that an end is accomplished in a novel and useful manner, then the idea ceases to be abstract, and becomes the proper subject of a patent. I, therefore, instruct you, that the open slot cut through one bar of a buckle in a cotton-tie, for the purpose set forth in Cook's third claim, is patentable; and, considered as separate and distinct from the other inventions covered by his patent, is a valid and patentable subject matter.

The court having thus disposed of the foregoing questions, it will be your duty to decide whether the defendant has, as alleged by the plaintiffs, infringed their rights under the Cook patent. In order that you may reach an intelligent conclusion on the subject, it is proper for the court to construe for you the third claim of Cook's patent, which is the only one alleged to be infringed by the defendant. What is secured by this claim is the right to use an open cut in a buckle, which, without the cut, would be a closed buckle, so as to allow the end of the tie or hoop to be slipped sidewise underneath the bar through which the slot is cut, and thereby to effect the fastening with greater ease, and obviate the necessity of the difficult process of pushing the end of the tie endwise under the bar. The specification and model are both in evidence, and you will have no difficulty in comprehending the idea of the inventor. The patent covers all the modes and processes by which the principle of the invention is made operative in practice. Tilghman v. Werk [Case No. 14,046]. The man who has made the first invention has it for all the uses to which it is applicable. Woodman v. Stimpson [Id. 17,070]. A man can not even have two patents for the same process, because for different purposes. When the means, devices, and organization are patented, the patentee is entitled to the exclusive use of this mechanical organization, device, or means for all the uses and purposes to which it can be applied—to every function, power, and capacity of his patented machine or device—without regard to the purposes to which he supposed originally it was most applicable. Conover v. Roach [Id. 3,125].

The plaintiffs claim the open slot in a buckle to facilitate the passage of the end of a cotton-tie under the bar of the buckle sidewise and not endwise. Now, he is entitled to the benefit of that device when that purpose is accomplished by the means provided, and substantially in the manner provided. If a party uses the open slot described in the third claim of this patent for passing the end of a cotton-tie sidewise under the slotted bar, it makes no difference whether such end is in the form of a loop or not, if the result attained is that the end of a tie has been “slipped sidewise through the slot underneath the bar, so as to effect the fastening with greater rapidity than by passing the end of the tie through endwise.” Then the result is the result claimed by the patent, and it is accomplished substantially by the means set forth in the patent. I say to you, therefore, that the third claim of the Cook patent covers the open slot in a cotton-tie buckle used for the purpose of passing the end of the tie sidewise through the slot under the bar, no matter by what other manipulation of the tie that result is attained; and I say to you, further, that it is not necessarily connected with the remainder of the Cook tie, and it covers the open slot used on other forms of buckle for substantially the same purpose, and in substantially the same way.

With these instructions in mind, you will decide the issue whether or not defendant has infringed upon the third claim of plaintiff's patent The defendant contends that the tie sold by him, and which has been exhibited to you, is not an infringement upon the patent of the plaintiffs; that the principle of the two is not identical, but different. Whether this is the fact, you must determine from the weight of the evidence, under the instructions of the court. If the device on the buckle sold by defendant for the purpose of passing the end of the tie under the slotted bar is substantially the same as the device claimed by plaintiffs' patent, then defendant has infringed upon plaintiffs' invention. The contrivances for the purpose in view must be substantially identical, and that is substantial identity which comprehends the application of the principle of the invention. If a party adopts a different mode of carrying the same principle into effect, and the principle admits of different forms, there is an identity of principle, though not of mode. Page v. Ferry [Id. 30,662]. And it makes no matter what additions to or modifications of a patentee's invention a defendant may have made: if he has taken what belongs to the patentee he has infringed, although with his improvement the original machine or device may be much more useful. Howe v. Morton [Id. 6,769]. All modes, however changed in form, but which act on the same principle and effect the same end, are within the patent; otherwise a patent might be avoided by any one who possessed ordinary mechanical skill. If you shall reach the conclusion that defendant has not infringed the patent of plaintiffs, that will conclude your duties on this branch of the case; but if you find he has infringed, it will then be your duty to pass upon the question of damages. The amount of damages is a question solely for your consideration; but it is the duty of the court to instruct you as to the rules of law by which the damages are to be estimated.

This rule is not what defendant made by 1295the infringement, or what he might have made, but it is the loss sustained by plaintiffs by reason of the infringement. The amount of this loss you must gather from the evidence. It is proper to inquire how many customers were diverted from plaintiffs by the wrongful conduct of defendant, and what loss plaintiffs have sustained in profits by reason of such diversions. If plaintiffs were ready to supply the market with their patented goods, and their business was hindered or interfered with by the competition of defendant, plaintiffs' damages will be the amount of profit which they have lost by reason of such interference.

It now remains to consider the other branch of the case—to wit, the defendant's claim in reconvention. This claim of defendant has already been stated in giving the substance of his answer, and you are to consider and determine from the proofs whether plaintiffs have infringed upon the patent of defendant. To assist you in this inquiry, it is the duty of the court to construe the letters patent under which defendant claims. The third claim in defendant's reissued patent covers a link made with an open slot, of such a construction that the tie can be introduced in the manner shown in figures 6, 7, 13, and 14, which permits the link to be turned after the hoop has been inserted. This patent of defendant does not cover the open slot, as claimed by plaintiffs. It is in proof, and there seems to be no controversy upon the point, that the plaintiff, J. J. McComb, has sold what is known to be the arrow-tie, and it is the sale of this tie which the defendant claims to be an infringement upon his patent I instruct you, if the arrow-tie is so constructed that it can not be turned after the tie is passed through the slot in substantially the same way as described in Brodie's patent, it will not infringe that patent But if it can be so turned, and is intended to be used in that way, or is so used by plaintiffs, then it is an infringement. The principles of law laid down in reference to the plaintiffs' branch of the case apply to and will govern the branch now under consideration. If, however, you should be of the opinion that plaintiffs have infringed on defendant's patent, you will not be authorized to return any damages for him if he failed to show that he has so complied with the law as to entitle him to recover damages. The act of congress, approved July 8, 1870, § 38 (16 Stat. 203), requires that every patented article sold shall be stamped with the word “patented,” and the day and year the patent was granted; and, in any suits for infringement by the party failing so to mark, no damages shall be recovered by plaintiff, except on proof that the defendant was duly notified of such infringement, and continued, after such notice, to make, use, and vend the article patented. So that, if defendant has neglected to prove that his patented article was stamped, or that he gave the notice required by the statute, you can not award him more than nominal damages. My recollection is that no such proof was offered; and, if this be so, you can return nominal damages only for defendant. This comprises all that I deem necessary to say, except to add that your duty is to approach the consideration of the case with minds unbiased and uninfluenced, save by the testimony, the arguments of counsel, and the charge of the court.

It is your duty to dismiss from your minds all preconceived opinions of the merits of this controversy, if any such you have, and decide the case as it has been submitted to you. Your function is to pass upon the issues of fact, applying the law as given you in charge by the court. Such is the rule for the administration of justice, and such is the obligation of your oath.

[The jury found a verdict for plaintiffs, and rejected the claim of defendant in reconvention. Upon the verdict, the court rendered judgment for plaintiffs, with costs.]2

[Patent No. 19,490 was granted to F. Cook March 2, 1858. For other cases involving this patent, see McComb v. Beard, Case No. 8,706; Cook v. Ernest, Id. 3,155; American Cotton Tie Co. v. Simmons, 106 U. S. 89, 1 Sup. Ct. 52.]

1 [Reported by Hon. William B. Woods, Circuit Judge, and by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here compiled and reprinted by permission. The syllabus and opinion are from 1 Woods, 153, and the statement is from 5 Fish, rat Cas. 384.]

2 [From 5 Fish. Pat Cas. 384.]

2 [From 5 Fish. Pat Cas. 384.]

2 [From 5 Fish. Pat Cas. 384.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.