Case No. 8,452.

15FED.CAS.—49

LOCOMOTIVE ENGINE SAFETY TRUCK CO. v. ERIE RY. CO.

[10 Blatchf. 292;1 6 Fish. Pat. Cas. 187; 3 O. G. 93; Merw. Pat. Inv. 440.]

Circuit Court, S. D. New York.

Dec. 30, 1872.

PATENTS—PILOT WHEELS IN LOCOMOTIVE ENGINES—INFRINGEMENT—ACT OF MAY 4, 1858—JURISDICTION.

1. The claim of the letters patent granted to Alba F. Smith, February 11th, 1862, for an “improvement in trucks for locomotives,” namely, “the employment, in a locomotive engine, of a truck or pilot wheels, fitted with the pendent links, o, o, to allow of lateral motion to the engine, as specified, whereby the drivers of said engine are allowed to remain correctly on the track, in consequence of the lateral motion of the truck, allowed for by said pendent links, when running on a curve, as set forth,” is a claim for the use in, and the combination with, a locomotive engine, (that is, a structure having, at its rear end, not a swivelling truck, but non-swivelling driving wheels, with axles rigidly attached to the body of the engine,) of a swivelling pilot or leading truck, provided with pendent links, to allow the forward part of the engine to move laterally over the truck, when the truck and the driving wheels are not together in a straight track, whereby the forward part of the engine can move onward in a line tangent to a curve, while the axles of the driving wheels are parallel, or nearly so, to the radial line of the curve, and the axles of the truck wheels also become parallel to the radial line of the curve, because the truck is made to swivel around the king-bolt, by the action of the rails on the flanges of the truck-wheels.

2. The nature of the invention covered by such claim, explained.

3. Such claim is not anticipated by the patent granted to Bridges and Davenport, May 4th, 1841, for an “improvement in railway-carriages,” although such patent shows the use, at each end of a railway-car, of a swinging bolster, in a truck swivelling on a king-bolt, the body of the car being; connected to the truck-frame by pendulous links, from which such body is hung, whereby a lateral motion of the truck is permitted, independently of the body of the car.

4. Nor is such claim anticipated by the patent granted to Kipple and Bullock, December 20th, 1859, for an “improvement in car-trucks.” although the mode of operation of the Kipple and Bullock truck, per se, in a car having a like truck at the other end, is the same, for all the purposes of the truck itself, that it is in a structure which has driving wheels at the other end.

5. Nor is such claim anticipated by the patent granted to Levi Bissell, August 4th, 1857, for an “improvement in trucks for locomotives.”

6. The arrangement of Bissell, explained.

7. The combination of Smith was patentable, because it produces a new mode of operation, and new results, in the structure as a whole, although 764the truck used by Smith was old, and as respects itself, in swivelling and in having a lateral movement, operates in the same way as it did in the car which had two of such trucks.

8. The fact that Smith's patent is granted for an “improvement in trucks for locomotives,” and that the truck he uses was old, and that his invention is really an improvement in locomotives, forms no objection to the validity of the patent.

9. Under a bill alleging an infringement by making and using the patented invention, the allegation is sustained by proof of using alone.

[Cited in Butz Thermo-Electric Regulating Co. v. Jacobs Electric Co., 36 Fed. 197.]

10. The 1st section of the act of May 4, 1858, (11 Stat. 272), which provides, that a suit not of a local nature, brought in a district in a state containing more than one district, against a single defendant resides, does not apply to a case where the single defendant is a corporation created by such state.

[Cited in Galveston, H. & S. A. Ry. Co. v. Gonzales, 151 U. S. 496, 14 Sup. Ct. 407; East Tennessee, V. & G. R. Co. v. Atlanta & F. R. Co., 49 Fed. 612.]

[Final hearing on pleadings and proofs.

[Suit brought upon letters patent [No. 34,377] for “improvement in trucks for locomotives,” granted Alba F. Smith, February 11, 1862.

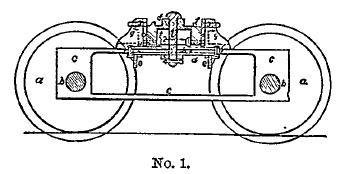

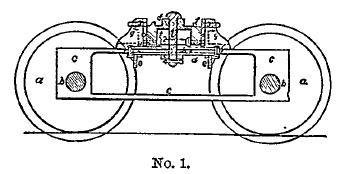

[Figure 1, in the above engraving, represents a vertical longitudinal section of complainant's truck, as shown in the letters patent. Figure 2 represents a transverse section of the same; d is the center cross-bearing plate or platform, made of two thickness of iron plate, riveted together, and embracing the upper bars of the frame c. At the end of said plate, e e are cross-bars, beneath the said double-bearing plate d, to strengthen the rivets; f is a bolster, made of a flanged bar, through the center of which the king-bolt i passes. The king-bolt also goes through an elongated opening in the plates d, so as to allow of lateral motion to the truck beneath the bolster. The king-bolt also serves as a connection to hold the truck to the engine. The bolster F is suspended from the side-pieces g g, of the frame, by means of pendent links o o, which links are shown in the engraving, No. 2, by dotted lines.

[A Further description of the structure and mode of operation will be found in the opinion of the court.

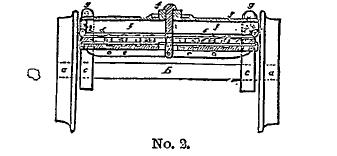

[Figure 3 represents the Davenport & Bridges truck, as shown in their patent.

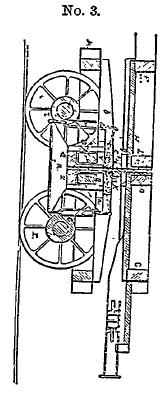

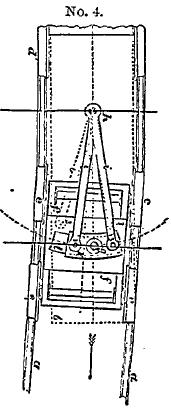

[Figure 4 shows the arrangement for securing lateral motion, in the Levi Bissell patent.

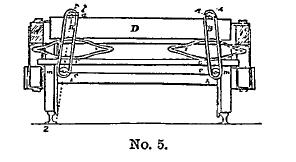

[Figure 5 represents the Kipple & Bullock truck, showing the arrangement of pendent links to permit lateral motion.]2

C. F. Blake and C. M. Keller, for complaint.

C. A. Seward, for defendant.

BLATCHFORD, District Judge. This suit is founded on letters patent granted to Alba F. Smith February 11th, 1862, for an “improvement in trucks for locomotives.” The specification describes the invention as an “improvement in trucks for locomotive engines.” It says: “Several laterally moving trucks have been made and applied to railroad cars. My invention does not relate broadly to such laterally moving trucks, but my said invention consists in the employment, in a locomotive engine, of a truck or pilot wheels provided with pendent links, 765to allow of a lateral movement, so that the driving wheels of the locomotive engine continue to move correctly on a curved track, in consequence of the lateral movement allowed by said pendent links, the forward part of the engine travelling as a tangent to the curve, while the axles of the drivers are parallel, or nearly so, to the radial line of curve. In the drawing, I have represented my improved truck itself. The mode of applying the same to any ordinary locomotive engine will be apparent to any competent mechanic, as my truck can be fitted in the place of those already constructed, or the same may be altered, to include my improvement.” The truck has four wheels, on two axles, and a frame made in the usual manner of the frame of an ordinary locomotive truck. It has a centre cross bearing plate or platform, made of two thicknesses of iron plate, riveted together, and embracing the upper bars of the frame; and a bolster, made of a flanged bar, through a hole in the centre of which the king-bolt passes. The king-bolt also goes through an elongated opening in the bearing plate, to allow a lateral motion to the truck beneath the bolster. At the same time, the king-bolt is a connection, to hold the truck to the engine. The bolster takes the weight of the engine in the middle, and is itself suspended at the ends of bars attached to the moving ends of the pendent links, which are attached by bolts, at their upper ends, to brackets on the frame. The distance between the bars, transversely of the truck, is slightly more than that between the bolts, so that the pendent links diverge slightly. The specification says: “When running upon a straight road, the engine preserves great steadiness, because, any change of position, transversely of the track, in consequence of the engine moving over the truck, or the truck beneath the engine, is checked by the weight of the engine hanging upon the links, and, in consequence of their divergence, any side movement causes the links on the side towards which the movement occurs, to assume a more inclined position, while the other links come vertical, or nearly so. Hence, the weight of the engine acts with a leverage upon the most inclined links, to bring them into the same angle as the others, greatly promoting the steadiness of the engine in running in a straight line. As the pilot or truck wheels enter a curve, a sidewise movement is given to the truck, in consequence of the engine and drivers continuing to travel as a tangent to the curve of the track. This movement, and the slight turn of the whole truck on the king-bolt, not only causes the truck wheels to travel correctly on the track, with their axles parallel to the radial line of the curve of track, but also elevates the outer side of the engine, preventing any tendency to run off the track upon the outer side of the curve. Upon entering a straight track, the truck again assumes a central position, and, in case of irregularity in the track, or any obstruction, the truck moves laterally, without disturbing the movement of the engine. I do not claim laterally moving trucks, nor pendent links, separately considered.” This claim is: “The employment, in a locomotive engine, of a truck or pilot wheels, fitted with the pendent links, o, o, to allow of lateral motion to the engine, as specified, whereby the drivers of said engine are allowed to remain correctly on the track, in consequence of the lateral motion of the truck, allowed for by said pendent links, when running on a curve, as set forth.”

The proof shows that the defendants have used, in this district, an engine, built by them at Dunkirk, in the Northern district of this state, which has four flanged driving wheels, and contains the invention claimed in Smith's patent. The issue is as to the novelty of the invention. In order to determine this question, it is necessary to clearly see what invention is claimed in Smith's patent.

He does not claim laterally moving trucks, that is, trucks with laterally swinging bolsters. Nor does he claim pendent links, by themselves. Laterally moving trucks, applied to railroad cars, which had at each end one of such trucks, free also to swivel around a king-bolt, which connected the car to the truck, and passed through the centre of the swinging bolster, which was the centre of the truck, were old. The specification so admits. But, Smith's invention, as claimed, is for the use in, and the combination with, a locomotive engine, (that is, a structure having, at its rear end, not a swivelling truck, but non-swivelling driving wheels, with axles rigidly attached to the body of the engine,) of a swivelling pilot or leading truck, provided with pendent links, to allow the forward part of the engine to move laterally over the truck, when the truck and the driving wheels are not together in a straight track, whereby the forward part of the engine can move onward, in a line tangent to a curve, while the axles of the driving wheels are parallel, or nearly so, to the radial line of the curve, and the axles of the truck wheels also become parallel to the radial line of the curve, because the truck is made to swivel around the kingbolt, by the action of the rails on the flanges of the truck wheels.

In going around a curve with a locomotive engine, the axles of the two pairs of driving wheels tend to assume a parallelism to that radius of the curve Which is equidistant between the two axles. If the pilot truck has no lateral swing to its bolster, but merely swivels on the king-bolt, the tendency of the action of the truck wheels, on a curve, is to force the king-bolt into a position over the centre of the track. That action is resisted by the body of the engine, and, to accomplish it, the driving wheels must be 766twisted out of their proper position, and must slip and grind on the rails. The reason of this is, that a line drawn longitudinally through the centre of the engine, at right angles to that radius of the curve which is equidistant between the two axles of its driving wheels, will not strike the king-bolt at the centre of the track, unless the driving wheels are so caused to slip. Hence, it was customary, with a pilot track which only swivelled, and had no lateral swing to its bolster, to make the front driving wheels without flanges, so that they might slide sidewise. But, the antagonism is reconciled, by allowing the king-bolt and the forward end of the engine to move laterally, so as to keep in a line substantially at right angles to the axles of the driving wheels, and outside of the centre of the track, the king-bolt being no longer controlled, in its position, by the truck, and there being no twisting of the driving wheels out of position.

Another feature, developed in the use of the pendent links, is pointed out in the specification, which is, that, on entering a curve, the outer side of the engine, as the truck moves inward laterally under it, is elevated, so as to counteract any tendency to run off of the track on the outer side, by the centrifugal action, and, as the mode of hanging the links causes the link on the outer side to assume a more inclined position, while the other link becomes more nearly vertical, the weight of the elevated engine acts to steady the engine, and restore it to a position midway between the rails, on returning to a straight track. This feature of the links also acts to keep the engine steady, when on a straight track.

The patent granted to Bridges and Davenport, May 4th, 1841, for an “improvement in railway carriages,” shows a swinging bolster, in a truck swivelling on a king-bolt, the body of the car being connected to the truck frame by pendulous links, from which such body is hung, whereby a lateral motion of the truck is permitted, independently of the body of the car, the sidewise motion being checked by springs in the truck. But, the specification of that patent does not suggest the use of such a truck in any other structure than a car having one of such trucks at each end, and two king-bolts. Nor did it, or the use of two of such swinging bolsters in a car, suggest, from 1842, to 1862, the combination of such a swinging bolster truck with a locomotive engine, for the purposes set forth in Smith's specification.

In the truck described in Smith's specification, the side springs of Bridges and Davenport are dispensed with, the divergence of the pendent links being used, instead, to check the sidewise movement. This precise construction of divergent links is shown in the patent granted to Kipple and Bullock. December 20th, 1859, for an “improvement in car trucks.” Their use has the tendency to elevate the outer side of the car on a curve, and the tendency to steady the body of the car through its weight on the links that are most inclined, and the tendency to limit the lateral movement, without using side springs. But, although the mode of operation of a Kipple and Bullock track, per se, in a car having a like truck at its other end, is the same, for all the purposes of the truck itself, that it is in a structure which has driving wheels at the other end, yet the moment the truck swivelling on a king-bolt is taken out of the other end of the structure, and driving wheels take its place, the mode of operation of the structure as a whole becomes different from the mode of operation of the structure with the two swivelling trucks. This is conceded by the expert for the defendants, and is quite manifest. The mode of operation becomes such as is described in Smith's specification, and no such mode of operation exists in the structure with the two trucks. Moreover, the existence of the Kipple and Bullock patent, and the use of cars each with two of their trucks, does not seem to have suggested, before the invention of Smith, the use of one of such tracks, as a pilot truck in a locomotive engine, to obviate the well-known difficulties in using the engine on a curve.

The only other pre-existing invention brought up to affect the novelty of the Smith invention, is the patent granted to Levi Bissell, August 4th, 1857 [No. 17,913], for an “improvement in trucks for locomotives.” Bissell's truck is shown used under the forward part of a locomotive engine. It has a provision designed to allow a lateral motion to the truck, independently of the motion of the body of the engine, and a provision to cause the forward part of the engine to mount up an incline, towards the outer side, in a curve, and thus cheek the sidewise movement, and to descend, by its gravity, to the normal position, on resuming the straight track. The specification of Bissell's patent says, that the object of his invention is, “to retain the truck with the axles always at right angles to the rail, whether on a straight or curved track, and prevent the truck swinging around on its centre pin, in case of meeting with any obstruction, and to make the curvature of the rail the means for turning the truck so that the axles are parallel to the radial line of the given curve, in which position they are retained firmly until the direction of the track again changes.” The specification then points out the difficulties, in the use of locomotive engines on curves, with the ordinary pilot truck, resulting in a “constant sidewise sliding motion on the rail,” in consequence of the driving wheels being forced in a line deflected from that of a cylindrical forward rolling motion, and in a constant bearing of the truck to the outer side of the curve, and in the tendency of the engine to go off the track, “particularly in case a broken rail or 767obstruction occurs, when the truck swivels around on its centre pin.” It then proceeds: “I, therefore, construct my truck in such a manner that the axles of the driving wheels shall be on the line of, or parallel to, the radial line of the curve, so as always to have a direct forward propelling motion, and not strain or wear the rail or flanges of the wheels, and so that two or more pairs of drivers can be fitted with flanges. Consequently, the centre line of the locomotive, in going around the curve, travels as a tangent to the centre of the drivers, and, to accommodate the curve, I fit the truck or forward wheels in such a manner as to allow of a transverse motion, the said truck swinging laterally upon an axis of motion, h, located centrally between the centre of the drivers and truck, (or slightly forward of the same,) so as to give a slight tendency to the truck to run to the inner side of the curved track. Thereby, the axles of the truck wheels are parallel (or nearly so) to the radial line of the curved rail, and the engine runs around any given curve without much more strain, either on the wheels or the track, than would occur on a straight railroad; and, at the same time, there is no chance for the truck to turn on its centre pin, by any obstruction coming in contact with the wheels, and the wheels will pass over a broken rail, and not be displaced, unless all four wheels are simultaneously unsupported, and, even then, the wheels and truck, being set correctly to the angular position with the drivers and the curvature of the track, will continue to move in the correct direction, and pass over any obstacle or broken rail, and attain the uninjured part of the track; and, in running on a straight track, the truck is held correctly in position, and will run over quite considerable obstruction without being turned aside. In running on either a straight or curved track, one of the truck wheels often breaks off, and the track swivels around on its centre pin in consequence, and throws the engine off the track; but, with my device, one wheel, or even the two wheels on the opposite sides diagonally of the truck, might break off, and still the truck would not run off, because its position is set, and it has no axis of motion around which it could swing, when injured as above stated, or when meeting a broken rail or any obstruction, but is given a direct forward propulsion; and, in all cases, the axles of my wheels have only a strain and torsion due to the difference of length between the outer and inner rails, instead of a strain due to the binding of the flanges of the wheels, from the diagonal position of the axles, in addition to the above named strain; hence, axles so often break when running around a curve. With my engine, the friction on the rails, in running around curves, is avoided, and I am enabled to maintain a nearly uniform speed, without any unusual strain or wear on any parts.” The specification of Bissell then describes the construction of his apparatus, with references to drawings. It says that the centre pin, (which is the king-bolt in the centre of the truck,) in his arrangement, “changes its character from a centre of motion, simply to that of a draft block or pin, while the centre of motion is thrown back to the point h, which is slightly forward of the centre between the drivers.” There is, at the centre of the truck, a block, whose longest direction is across the track, and whose longest sides are parts of circles, of which h is the centre, or, as the specification expresses it, “curved from the centre h.” There is a similar curved slot in the top plate of the truck frame, which slot is sufficiently long to allow of the lateral movements of the truck, when the locomotive is on a curve of the smallest radius that it ever has to travel over. The curved block might, it is stated, be bolted directly to the under side of the engine, and the curved slot would bring the axles of the wheels parallel with the radial line, or nearly so; but, to allow an easier motion to the parts, the blocks may be prevented from turning by radius bars leading to the centre h. The patentee states, however, that he prefers that the radius bars should be attached to the truck frame, so as to cause the truck to swing on the centre h, in which case the curved block may be made use of, or the centre pin be fitted to move in a curved slot. He then describes the arrangement and use of the inclines before mentioned, to check the lateral motion.

It is apparent, that the track, in Bissell's locomotive, has no swivelling motion around its centre pin or king-bolt, that is, around the centre pin in the centre of the truck, which connects the track with the engine. Bissell expressly states, that such centre pin loses its character as a centre of motion, and becomes simply a draft block or pin, and that the centre of motion of the truck, that is, its only centre of motion, is thrown back to the point h, outside of the trade. He further says, that, although his truck has a centre pin, it has “no axis of motion around which it could swing.” It has only a motion in the arc of a circle, of which the pin h, located between the truck and the driving wheels, is the centre, such motion being a swinging motion of the whole truck across the track. It follows, inevitably, that the position of the pin h regulates the position of the axles of the truck relatively to the track, and that the absence of free swivelling in the truck around its centre prevents the action of the rails on the flanges of the truck wheels from regulating the position of such axles on a curve. When the pin h is equidistant between the centre between the axles of the driving wheels and the centre between the axles of the truck wheels, the axles of the truck wheels may, on a curve, be in their proper position, that is, parallel to a radius of such curve half way between such axles. But, that is not true in reference to any other 768position of the pin h; and, even when the pin h is in that position, the axles of the truck wheels can never be in such proper position, when the engine is entering a curve, or leaving a curve, or changing from a curve in one direction to a curve in another direction, because, the position of such axles depends on the position of the pin h with reference to the track, and the driving wheels control the position of the pin h. A geometrical demonstration shows, that, if the pin h be equidistant from the centre between the axles of the drivers and the centre between the axles of the truck wheels, the axles of the drivers and the axles of the truck wheels will, when they are all on the same curve, be in their proper positions; that, if the pin h is not thus equidistant, one or the other set, or both sets, of axles will, on the same curve, be in a wrong position; that, when the drivers are on a curve, and the truck wheels are on a straight part of the road, the pin h can never be in such a position as to allow the axles of the truck wheels and the axles of the drivers, all of them, to be in their proper positions; and that this holds equally true when the truck wheels are on a curve and the drivers are on a straight part of the road, and, also, when the truck wheels are on one curve and the drivers are on, another curve. The action of the drivers, through the pin h, is to twist the truck wheels on the track, and control the position of their axles, in correspondence with the direction of the longitudinal centre line of the engine.

In the engine of Smith, the truck wheels and the drivers can, at all times, when the engine is on a curve, and when it is entering a curve, and when it is leaving a curve, and when it is passing from a curve in one direction to a curve in another direction, take their proper positions respectively, without either being controlled or interfered with by the other. The reason for this is, that the truck, in the Smith engine, has a swivelling motion on its king-bolt, and also admits of the swinging motion, across the track, of the engine over the truck, or the truck under the engine. Neither of these motions affects the other. If either motion interfered with the other, the same result would follow as in Bissell's engine, and the position of the drivers would, at times, control the position of the axles of the truck wheels. But, with Smith's arrangement, the track alone controls the position of the axles of the truck wheels, and, therefore, they assume their correct position on any track, straight or curved, and on any form of curve, and whether the drivers are on a straight track with the truck wheels, or on the same curve with the truck wheels, or on a straight track while the track wheels are on a curve, or on a curve while the truck wheels are on a straight track, or on one curve while the truck wheels are on a different curve. This is a result not attained in Bissell's engine, and it results from the fact that the arrangements and modes of operation of the two structures are different. The truck wheels, in Smith's engine, are never twisted on the track, and the direction of the longitudinal centre line of the engine does not affect the position of their axles.

It results, from these considerations, that, in the engine, as a whole, the Smith arrangement of track is not merely an equivalent for the Bissell arrangement of track; because, when the former is substituted for the latter, the resulting structure has a different mode of operation and produces results which the other structure cannot produce. The thing to be looked at is the combined and mutual action of the drivers and the track wheels, for that was the problem which both Bissell and Smith were trying to solve. Smith's claim is, substantially, a claim to the combination with the drivers, of a track arranged as he describes, allowing of the lateral motion described, and securing the proper position of the drivers on the track, on curves. That combination is not found in Bissell's engine.

It needs no argument to show, in view of the foregoing considerations, that there was a patentable novelty in the combination which Smith made in his engine, although the truck which he employed existed before, as the Kipple and Bullock truck. The combination produces a new mode of operation, and new results, in the structure as a whole, although the truck, as respects itself, in swivelling, and in having a lateral movement, operates in the same way as it did in the car which had two of such trucks. It was not apparent, without experiment, that the use of a swinging bolster swivelling truck, in an engine, would relieve all the difficulties attendant on the use of driving wheels on curves. If it had been, Bissell would have adopted the truck of Bridges and Davenport, instead of resorting to the contrivance he made. Hence, what Smith did was not, as is urged, merely to apply an old contrivance, in an old way, to an analogous use.

It is urged, that Smith's patent is void, granted, as it is, for an “improvement in tracks for locomotives,” because, although he may have invented a combination of the truck with a locomotive, yet he invented no improvement in the truck, but used the truck of Kipple and Bullock; that the invention of such combination is the invention of an improvement in locomotives, or of a new locomotive, or of an improved locomotive, or of a combination of truck and locomotive; and that the patent is void as a patent therefor, because it is not granted as a patent therefor, but is granted as a patent for an “improvement in tracks for locomotives.” In this connection, reference is made to the fact, that, in his specification, Smith says, that figure 1 of his drawings is “a plan of my truck;” and, also, that, “in the drawing, I have represented my improved truck itself;” 769and, also, that “my truck can be fitted in the place of those already constructed.” The body of the specification speaks of the invention as an “improvement in trucks for locomotive engines.” The statute required that the patent should contain a short description or title of the invention, correctly indicating its nature and design. This patent substantially conforms to the statute. As a truck to be used in a locomotive engine, the truck Smith describes as to be employed, is an improvement on Bissell's truck employed in an engine. Smith's invention is an improvement in the use of trucks in locomotive engines, an improvement in the use, for locomotives, of trucks. It is a new and useful improvement; and the class of inventions to which it belongs, the class which embraces its nature and design, is that of trucks for locomotives, trucks used in locomotives. The claim is, to the employment, in a locomotive, of a truck constructed in a certain way, and producing a certain result, in the action of the drivers, on a curve. The title in the patent does not require that the claim should be one to an invention in respect to the truck per se. The expression, “my truck,” in the specification, has reference, obviously, when the statement of the nature of the invention, and the claim, are considered, to the truck which Smith describes as the one he was intending to use in the engine, to produce the results specified. The patent, therefore, is not open to the objections thus urged.

The answer sets up, that the larger portion of the road of the defendants, and of the operations thereon conducted, is not within the jurisdiction of this court; that all of the engines built by them, which are alleged to infringe the Smith patent, were constructed by them at Dunkirk; that the use of said engines is largely confined to the western division of their road; and that such construction and larger use were not, and are not, within the jurisdiction of this court. It is contended, for the defendants, that, as the bill avers that they “have constructed and built, and caused to be constructed and built, and are now using, trucks for locomotives, constructed in accordance with, and containing and embodying,” the invention patented by Smith, and that the plaintiffs “have reason to believe that they will continue to make and use the same,” and that the defendants refuse to pay the plaintiffs any profits which they have realized from “such unlawful making and using,” and, as the bill prays that the defendants may be decreed to pay to the plaintiffs the profits which they have made “by reason of such unlawful manufacture and use,” and may be enjoined “from making, constructing and using trucks for locomotives constructed substantially in accordance with” the patented invention, the bill is based on the making and using, in the conjunctive; that its frame is such, therefore, that, if the plaintiffs cannot, under it, recover for the making, they cannot for the using; that they cannot, in this suit, recover for the making of the only engine proved to have been made or used by them, containing the invention patented, because, although such engine is proved to have been used in this district, it is proved to have been made in the Northern district of this state; that, by the 6th section of the act of April 3, 1818 (3 Stat. 415), the original jurisdiction of this court is confined to causes arising within this district, and is declared not to extend to causes of action arising within the said Northern district; that the cause of action arising out of the making of such engine is, therefore, not within the jurisdiction of this court; and that, as the bill is founded on the making and using, there can, consequently, be no recovery whatever under it, on the evidence as to the one engine.

I do not think these views are sound. They overlook the fact, that the bill avers that the defendants refuse “to desist from using” the invention patented; that the grant, in the patent, is of the right “of making, constructing, using, and vending to others to be used;” that an infringement may be committed by making, or constructing, or using, or vending to others to be used; that an allegation, in the bill, of making or using, would be bad pleading; and that an allegation of making and using, is proved, to all intents and purposes, by proof of using alone. Indeed, the allegation, in the bill, that the defendants have “constructed and built, and are now using, trucks for locomotives constructed in accordance with, and containing and embodying” the patented invention, is, by no means, an allegation which necessarily implies that any of the structures which are used by the defendants were built by them, or that any of the structures which were built by them are used by them. It may as properly be read, that they have constructed infringing structures, and that they are, also, using infringing structures.

Under this bill, therefore, the plaintiffs, having proved an infringement by the use, in this district, of the engine referred to, are entitled to a decree for an accounting by the defendants in respect of all infringements committed in this district, by making or using, or vending therein; and to an injunction against making in this district, and against using therein, and against vending therein. If the plaintiffs desire to proceed for an account and an injunction in respect of infringements in the Northern district, they must proceed by bill filed there. The defendants are suable in the circuit court for that district, their legal existence, under their incorporation by the state of New York, being co-extensive with the territorial limits of that state.

The 1st section of the act of May 4, 1858 (11 Stat. 272), which provides, that “all suits 770not of a local nature, hereafter to be brought in the circuit and district courts of the United States, in a district in any state containing more than one district, against a single defendant, shall be brought in the district in which the defendant resides,” has no application to this case. Although this suit is one not of local nature, that is, is what, if it were a suit at law, would be a transitory action, yet the act has no application to a case where the single defendant resides as fully in all the districts in the state as in any one of them. A corporation, if it can be properly said to “reside” at all, resides in all the districts of the state creating it. It is doubtful whether the act applies to corporations.

A decree will be entered in accordance with the foregoing directions, with costs to the plaintiffs.

[For other eases involving this patent, see Locomotive Engine Safety Truck Co. v. Pennsylvania R. Co., Case No. 8,453, and note.]

1 [Reported by Hon. Samuel Blatchford, District Judge, and by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here compiled and reprinted by permission. The Syllabus and opinion are from 10 Blatchf. 292, and the statement is from 6 Fish. Pat. Cas. 187.]

2 [From 6 Fish. Pat. Cas. 187.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.