Case No. 7,827.

14FED.CAS.—40

KINNEY v. CONSOLIDATED VA. MIN. CO. et al.

[4 Sawy. 382.]1

Circuit Court, D. California.

Nov. 1. 1877.

MINING LAWS AND CLAIMS—DECREE WITHOUT ALLEGATIONS TO SUPPORT IT—MISTAKES FOR AND AGAINST GRANTOR—UNSTAMPED CONVEYANCES AND SUBSEQUENT STAMPED CONVEYANCES—UNSTAMPED CONVEYANCE REPUDIATED—EQUITY—CONVEYANCE TO DEFRAUD CREDITORS—EQUITY—INFERENTIAL OR ARGUMENTATIVE PLEADING—CONSCIOUS IGNORANCE—MISTAKE, WHEN CORRECTED IN EQUITY—NEGLIGENCE—MISTAKE—LACHES—MISTAKE—STATU QUO—EFFECT OF CONVEYANCE, PENDENTE LITE, WITHOUT ACTUAL NOTICE OF PRIOR UNSTAMPED DEEDS—PAROL CONVEYANCE OF A MINING CLAIM VALID—THE UTAH STATUTE OF CONVEYANCE—NO MISTAKE.

1. Where a mining claim is made and actually possessed and worked for several years, the claim and location being generally recognized as valid by the miners in the vicinity, the title of the claimant is good, even though the location may not have been originally made in strict accordance with the mining rules in force at the time, especially so are between the co-claimants and their grantees.

2. Where, in an action under the statute of Nevada, by a portion of the owners in possession of a mining claim against parties out of possession, to determine an adverse claim on a complaint alleging only title and possession in plaintiffs, and the adverse claim of defendants, a decree had been rendered in favor of the complainants; and at a subsequent term of the court, without further intermediate proceedings, a supplemental decree was entered, purporting to be by consent, adjudging the title to the nortn twenty feet to be in two of the plaintiffs, and that the title to the remaining portion of the claim remained in all the plaintiffs, according to their respective rights: Selil, that the supplemental decree is void, as a decree of the court, on the grounds: 1. That there are no allegation in the pleadings or record upon which to base it; 2. That it was made after the rights of the parties had been adjudicated, and the case had been fully ended, and the term of the court thereafter finally adjourned; 3. That a portion of the co-owners were not parties to the proceeding, and their interests could not be affected.

3. Such supplemental decree, where treated as valid, and subsequently acquiesced in for several years by the parties interested, may possibly be regarded as written evidence of an agreement to partition upon the terms specified in the decree.

4. Kinney, the principal plaintiff in the case, since said decree; and Kinney and the defendants in this case in the transaction now in question, having acted upon the hypothesis that twenty feet were set off to Kinney and Welton 612in severalty, by said supplemental decree, without any mistake of fact on Kinney's part, and this being the only hypothesis upon which derendants can obtain all the interest in said mine, which they have purchased from Kinney and his grantees, and paid for, equity requires that the court should act upon the same hypothesis, and there is no such mistake as a court of equity will correct.

5. If a party, in making a conveyance of one part of a mining claim, makes a mistake against himself as to the amount conveyed, and in another part of the same conveyance makes a mistake in his favor of a corresponding amount in another portion of the same mine, and the grantee obtains no more in the aggregate than he purchased and paid for, the equities are equal, and a court of equity will not, on the application of the grantor, reform the conveyance by correcting the mistake against him, to the injury of the other party upon the entire transaction.

6. Where a party, while the acts of congress requiring conveyances to be stamped are in force, makes a conveyance without affixing a stamp thereto, and the grantee in such unstamped conveyance conveys subsequently by deed, duly stamped and in all respects valid, the grantee under the deed properly stamped takes the title unaffected by the failure to stamp the prior deed.

7. Where K. conveyed interests in a mining claim to W. and M., respectively, by unstamped conveyances, who afterward conveyed the same to O. by conveyances good in form; and K. afterward conveyed his remaining interest to C., and then filed a bill in equity against C. to correct an alleged mistake in the latter conveyance, on the ground that he conveyed more than was intended; and in order to make out the mistake it is necessary to repudiate his former unstamped conveyances to W. and M., a court of equity will not correct the mistake in order to allow him to avail himself of the advantages to result from repudiating his prior unstamped conveyances. Equity requires that he should make good his prior void conveyances, and he who asks equity must do equity.

8. A conveyance given for the purpose of putting property beyond the reach of creditors is fraudulent, and a court of equity will leave the parties where it finds them. It will refuse the fraudulent grantor any relief founded upon the idea that tie grantee holds the property thus fraudulently conveyed in trust for his benefit; and no such trust will be recognized in equity for the purpose of working out a mistake, to serve as the foundation for reforming a subsequent conveyance from the grantor to parties taking through the fraudulent grantee, without notice of the fraud, and holding the property fraudulently conveyed.

9. Inferential or argumentative pleading is inadmissible. A fact can only be put in issue by a direct allegation in such form that the other party can take issue directly upon it.

10. Where parties deal with each other with the knowledge, and in view of the fact, that something is uncertain as to the amount or condition of the subject-matter of their dealings, and the contract relating thereto is in-the form intended, there is no ground for correcting a mistake in a court of equity, if it should finally turn out that one has intervened.

11. Relief on the ground of mistake in cases of written instruments will only be granted where there is a plain mistake clearly made out by satisfactory proofs.

12. Mistake, to be available in equity, must not have arisen from negligence where the means of knowledge are clearly accessible. The party complaining must have exercised at least the degree of dillgence which may be fairly expected $$$ person.

13. Where a party desires relief in equity on the ground of mistake, he must act promptly on discovery of the mistake, or he will be regarded as waiving the objection, and be bound by the contract to the same extent as if no mistake had occurred. This is specially true in the case of speculative property which is liable to large and constant fluctuations in value.

[Cited in Great West. Min. Co. v. Woodmas of Alston Min. Co., 23 Pac. 911.]

14. A court of equity is reluctant to grant relief on the ground of mistake, unless the parties can be put in statu quo. If this cannot be done, it will grant such relief only where the clearest and strongest equity imperatively demands it.

15. K. conveyed portions of a mining claim by unstamped and unrecorded deeds to W., M. and L., who, together with their grantees, by various deeds, conveyed the same to C. K. subsequently conveyed to C. all his interest in the same mining claims by valid deeds duly recorded, and C. went into possession under said several conveyances. K. afterward filed a bill in equity against C. to correct a mistake in his said conveyance to C., and, pendente lite, conveyed all his interest in said mine to one of his counsel of record in the case and another, without actual notice of the said prior unstamped and unrecorded deeds, and said parties were made parties by supplemental bill simply alleging the conveyance pendente lite: Held—1. That C., having a good conveyance upon record from K., of all his interest in the mine, and being in possession, there was nothing left in K. which he could convey to his said grantees, pendente lite, except such equity as he had as against C. to have his prior conveyance reformed on the ground of mistake; 2. That if K. had no equity to reform his said deed, and K.'s said grantees, pendente lite, took any equities as against K.'s prior grantees under said unstamped and unrecorded deed, then C. having before obtained conveyances from said prior grantees in the unstamped and unrecorded deeds, had their equities, which were at least equal to the equities of K.'s said grantees pendente lite: and C. being in possession his possession is best, and a court of equity will not interfere to disturb it; 3. That by purchasing the subject-matter of the suit, pendente lite, the said grantees of K. took with notice of all the rights of defendants, and subject to any judgment or decree that might be entered in the case; and since no new equities were alleged, but only a transfer of the subject-matter of the action, with a prayer for the same relief, the decree must be the same as it would have been between the original parties; 4. That the actual sole possession of the defendants of the mine at the time of the said conveyance, pendente lite, imparted notice to the purchasers of the title and all equities of defendants: 5. That the purchasers pendente lite, Smith and Bryant, are in no better position than the complainant, their grantor.

16. In early days, in Nevada, the actual transfer of the possession of a mining claim with a view of passing the title followed by an actual possession of the transferee, acquiesced in by the party transferring it was a valid transfer of such claim. Any other ruling would disturb many old and valuable titles on the Comstock lode.

17. The Utah statute of conveyance of January 18, 1855, had no application to mining claims.

18. There was no mistake in the conveyance in question.

Bill in equity to reform a deed to a portion of a mining claim on the ground of mistake. Prior to April, 1872, complainant, Kinney, owned an interest in the mining ground then known as the Kinney ground, and the Kinney and Welton ground, within the lines of 613what was then the Consolidated Virginia Mining Company's claim. Sometime prior to this date he had expressed a wish to defendant, Heydenfeldt, that the Consolidated Virginia Mining Company would purchase his interest. The proposition was made, hut declined on the ground that, at that time, the mine was being prospected by assessments without knowing whether it was valuable or not; but the company offered to take Kinney's interest, and issue stock for it. This was declined on the ground, that he could not pay the assessments on the stock then being levied for working the mine. In April, 1872, defendant Flood, was desirous of buying in all outstanding claims to ground within the company's lines; and among others mentioned complainant's ground. Thereupon defendant, Heydenfeldt, wrote to Kinney at Eureka, Nevada, that there was a probable opportunity of selling his ground. On April 7, 1872, defendant, Heydenfeldt, in response to said letter, received from complainant Kinney, a telegraphic dispatch as follows, to-wit: “Eureka, April 7, 1872. Received at San Francisco, April 7, 1872, 7.10 p. m. To Hon. S. Heydenfeldt: Wrote to-day. Will send deed to-morrow; sell all I have at your own price. G. W. Kinney.”

A few days thereafter, the defendant, Heydenfeldt, received from complainant a letter, in words and figures as follows: “Eureka, Nevada, April 7, 1872. Hon. S. Heydenfeldt, San Francisco, Cal—Dear Judge: Your favor of the fourth instant is received and contents noted. I own the undivided one-half of the twenty feet and one-tenth of a foot adjoining the Central No. 2 on the south, unincumbered. This is the ground I spoke to you about. Sunderland, when president of the Consolidated Company offered me $800 for it once, for the purpose of absorbing it in the Consolidated Company. The abstract in possession of the company shows that I only own two feet (or twenty shares) in the Kinney ground, proper. There should be five (5) feet more. This five feet, as I understand it, stands in the name of Luther R. Mills (cousin of D. O. Mills). I hypothecated this amount to him once, and always thought (until I saw your abstract) that it had been properly reconveyed. You understand the position of things much better than I do. Act for me, judge, as you think best. There will be no quarrel between us as to price. I have been poor too long. Not having signed the incorporation of the Virginia Consolidated Company, I have paid no assessments. I do not know where L. R. Mills is, and would like to convert the shares into cash. To-morrow I will send you a deed to anything I may have on the Comstock range, and also a power of attorney, so that you can take your choice of mode of operating. Sell the ten feet in the twenty at your own price, and I will be satisfied; and also whatever your abstract allows me in the Kinney ground proper. The stage will start soon. Truly yours, Geo. W. Kinney. P. S. Act fully as for yourself, and I will indorse what you do. K.”

In a day or two afterward, defendant, Heydenfeldt, received from complainant another letter, in words and figures as follows: “Eureka, Nevada, April 8, 1872. Hon. S. Heydenfeldt, San Francisco, Cal.—Dear Judge: Yours of the fourth instant received and hurriedly answered yesterday. I also sent you a telegram same day. I inclose a deed to my interest in ‘Kinney and Welton,’ and ‘Kinney in Virginia district, and the Defiance’ in Gold Hill district. This latter may be of no value to you now, but sometime it may have. It was located and recorded in 1860, and lies directly in front of the Overman. The Overman Company subsequently took possession of the ground adverse to the Defiance. Before the limitation law of Nevada went into effect, suit was brought to recover the ground, with Quint & Hardy as attorneys. Not having been in that part of Nevada since, I do not know what became of it. The location was originally made with the assent and knowledge of Overman. Of the value of the property in Virginia district, you know much better than I do, and you are at liberty to name a reasonable price yourself, believing that you will do right by me. The consideration in the deed is left blank, for you to fill up. The segregated twenty feet adjoining the Central No. 2 is as I loft it in 1865, still on the judgment-roll, No. 1010, or 1110, I forget which. A few days prior to my leaving San Francisco, you showed me the abstract of the ground within the lines of the Virginia Consolidated Company. This showed me an owner to the extent of two feet only. I stated there was five feet lost to me in some way. Mr. Thomas Wallace wrote me saying there was five feet standing in the name of L. R. Mills. I once hypothecated this amount of ground to Mills, redeemed it, and always supposed that it had been properly reconveyed. Mills owned of his own right four feet; but some years ago sold his interest to Frank Livingstone; so that if any stock is in Mills's name, there is where my missing shares are. Welton's interest should be in my hands, as he owes me about $1000. The consideration being left blank in the deed, you will please place the proper stamps, and deduct from what is due. Nevada requires the same additional amount as Uncle Sam. I hope you will be able to do something for me, as my finances have been low for several years. Sutro's map of the Comstock was made just before the twenty feet above named was given to Welton and myself, and of course does not appear there. It would have done so, but that it was unknown then. Yours truly, Geo. W. Kinney, Mining Recorder, Eureka District, Nev., Com. for Cal.”

At the same time, defendant Heydenfeldt also received a deed from complainant, a copy of which is hereto annexed and marked 614“Exhibit A:” “(Rev. Stamp, $1.50, canceled.; (Nevada State Stamp, $1, canceled.) (Nevada State Stamp, 50c., canceled.) This indenture, made the sixth day of April, in the year of our Lord 1872, between Geo. W. Kinney, of Lander county, Nevada, party of the first part, and S. Heydenfeldt, of the city and county of San Francisco, state of California, party of the second part, witnesseth: That the said party of the first part, for and in consideration of the sum of $1200, gold coin of the United States of America, to him in hand paid by the said party of the second part, the receipt whereof is hereby acknowledged, has remised, released, and forever quitclaimed, and by these presents, does remise, release, and forever quitclaim unto the said party of the second part, and to his heirs and assigns, all the following described locations, mining rights or claims, located on the Comstock lode, Virginia mining district, Storey county, state of Nevada, to wit: The undivided one-half part of the mine known as the ‘Kinney and Welton;’ said ‘Kinney and Welton’ mine consists of twety and one tenth (201/10) feet on the ledge or lode, and adjoins the ‘Central No. 2’ mine on the south. Also all the interest of said party of the first part in the mine known as the ‘Kinney,’ (amount unknown); said ‘Kinney’ mine adjoins the ‘White and Murphy’ mine on the north, and consists of fifty (50) feet on the ledge or lode; and also an undivided interest in one hundred (100) feet in the mine known as the ‘Defiance’; said ‘Defiance’ mine is situated in the Gold Hill mining district, Storey county aforesaid; was located in the year 1860 by John G. Hatch, Geo. W. Kinney and others, and duly recorded in the records of said Gold Hill mining district. Together with all the dips, spurs and angles, and also all the metals, ores, gold and silver-bearing quartz, rock and earth therein; and all the rights, privileges and franchises thereto incident, appendant and appurtenant, or therewith usually had and enjoyed; and also all and singular the tenements, hereditaments and appurtenances thereunto belonging, or in anywise appertaining, and the rents, issues and profits thereof; and also all the estate, right, title, interest, property, possession, claim and demand whatsoever, as well in law as in equity, of the said party of the first part, of, in, or to the said premises, and every part and parcel thereof, with the appurtenances. To have and to hold, all and singular the said premises, together with the appurtenances and privileges thereto incident, unto the said party of the second part, his heirs and assigns forever. And the party of the first part, for himself and heirs, covenants and agrees with said party of the second part, that said premises are now free from all incumbrances. In witness whereof, the said party of the first part has hereunto set his hand and seal the day and year first above written. (Signed) Geo. W. Kinney. (Seal.) (Duly acknowledged.)”

After receiving the telegram, letters and deeds, the defendant, Heydenfeldt, bargained and sold to the said Flood the ten feet and the one-twentieth of a foot of Kinney and Welton ground, and two feet of Kinney ground, this being all that the abstract of title, hereinbefore mentioned, showed to be vested in the said complainant. Heydenfeldt, by direction of Flood on April 12, 1872, conveyed to the Consolidated Virginia Mining Company in pursuance of the sale. The descriptive part of the deed is as follows: “All the following described locations, mining rights or claim located on the Comstock lode, Virginia mining district, Storey county, state of Nevada, to wit: The undivided one-half part of the mine known as the ‘Kinney and Welton.’ Said ‘Kinney and Welton’ mine consists of twenty and one-tenth (20 1/10) feet on the ledge or lode, and adjoins the ‘Central No. 2’ mine on the south. Also all the interest of said party of the first part in the mine known as the ‘Kinney’ (amount unknown). Said ‘Kinney’ mine adjoins the ‘White and Murphy’ mine on the north, and consists of fifty (50) feet on the ledge or lode, together with all dips, spurs and angles, rights, privileges, easements and franchises thereunto belonging, or in anywise appertaining, together with all and singular the tenements, hereditaments, and appurtenances thereunto belonging, or in anywise appertaining, and the reversion and reversions, remainder and remainders, rents, issues and profits thereof; and also all the estate, right, title, interest, property, possession, claim and demand whatsoever, as well in law as in equity, of the said party of the first part, of, in or to the said premises, and every part and parcel thereof, with the appurtenances.” Heydenfeldt informed Kinney of the sale of all his interest by telegraph on April 13, and soon after received in reply a letter, as follows: “Austin, Nevada, April 24, 1872. Hon. S. Heydenfeldt, San Francisco, Cal.—Dear Judge: Your dispatch of the thirteenth, informing me of the sale of all the property named in my deed to you, was received. I hoped to have received a letter from you on the subject, but so far I do not hear from you. Today I have drawn on you in favor of Wallace Everson, agent of New England Mutual Life Insurance Company, for $100 coin. Will also, in a few days, draw for about $210, favor Edwin Robinson, Santa Barbara; and also about $25, favor California Pioneer Society. Will you write and let me know if the five feet standing in the name of L. R. Mills was sold at the same time? Came here yesterday as a witness in the case of Street (Geo. Hearst) v. Lemon M. & M. Co. Hope to get away again to Eureka soon. Yours truly, Geo. W. Kinney.”

Kinney afterward drew on Heydenfeldt seven several drafts of various amounts for the purchase money which were paid; one of date April 13, one of May 6, two of May 15, two of May 17, and one of May 18. More 615than two years thereafter elapsed before Kinney indicated to Heydenfeldt any dissatisfaction with the transaction. During the intermediate time the great bonanza had been developed in the Consolidated Virginia mine.

On December 10, 1874, the complainant Kinney filed his bill in this case which was afterward amended. In the amended bill he alleged that on the sixth day of April, 1872, he was the owner of certain mining ground described as follows: “(1) The undivided ten feet and one-twentieth of one foot of ground on the Comstock ledge, so called, and in that portion thereof described as the northerly twenty feet and one-tenth of a foot of a certain mining location made on the twenty-first day of September, 1859, by plaintiff in his own name and for his own use, in Virginia mining district, whereby he located sixty feet in extent of said ledge, commencing five hundred and fifty feet southerly from the southerly line of Comstock's claims, now known as the Ophir Silver Mining Company's ground—said premises being now known as the Kinney and Welton ground. (2) An undivided interest of twenty-two sixtieths in all that portion of said Comstock lode, thirty-nine feet and nine-tenths of a foot in extent, lying directly south of the parcel of ground last above described. (3) The undivided five feet and one-twentieth of a foot in the portion of said Comstock lode, ten feet and one-tenth of a foot in extent, lying directly south of the last mentioned portion of said lode; said second and third parcels being known as the Kinney ground.”

That he applied to defendant, Heydenfeldt, to sell the same, which Heydenfeldt undertook to do; that to facilitate the transaction he executed to Heydenfeldt the deed hereinbefore set out; that the deed was executed for the purpose of enabling Heydenfeldt to sell and convey two feet undivided in the Kinney ground; and was delivered with written instructions to sell said two feet undivided in the Kinney ground; that Heydenfeldt sold to defendant Flood said two undivided feet at $000 per foot; that in pursuance of such sale, Heydenfeldt conveyed to the defendant, the Consolidated Virginia Mining Company, by said deed hereinbefore set out “intending by such conveyance and said company intending to acquire only two feet undivided in said Kinney ground;” that by said deed an apparent title was conveyed to all the interest of complainant; that said conveyance was made to include such property by mistake on the part of Heydenfeldt. A subsequent conveyance to the California Mining Company is alleged, and that both of said mining companies took with notice of the mistake. The property conveyed by mistake is alleged to be worth upwards of $950,000. It is also alleged that the said two mining companies, defendants, have taken out of said mining ground so owned by complainant, and converted to their own use, ores of the value of more than $20,000,000. He asks that he may be decreed to be the owner of the interests before mentioned in said divisions one, two and three, set out; that the mistake be corrected, and the interest reconveyed by said defendants; and for an account of the ores removed.

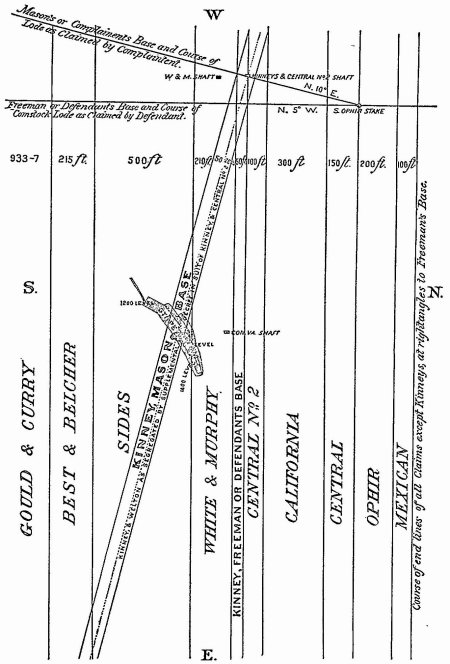

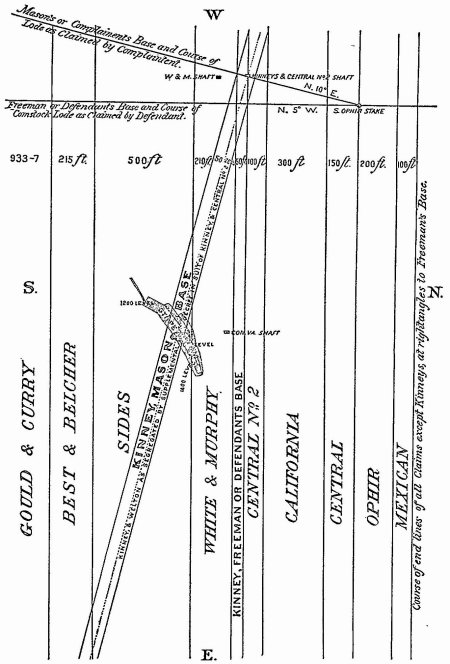

The answers admit the making of the conveyances set out; deny the mistake; allege the sale of what Heydenfeldt was authorized to sell, and no more; that it was intentionally done, and that the sale was for full value; that the sale was made for two feet in the Kinney and ten and one-twentieth in the Kinney and Welton; that Kinney was informed of the sale of all, and afterward received the purchase-money without objection. Upon the coming in of the answers, and at the hearing, a part of the claim set up in the bill was abandoned by complainant, and it was admitted that the ten and one-twentieth feet on the north end of the claim, called in the deed and bill the Kinney and Welton ground, and two feet undivided in the ground described in the said deed of Kinney thus: The “Kinney mine adjoins the White and Murphy mine ‘on the north, and consists of fifty (50) feet on the ledge or lode,” it being now claimed to be the fifty feet next south of the Kinney and Welton, shown in the accompanying diagram, and drawn on the diagram upon the “Mason or Defendants' Base” was properly conveyed. Upon this admission, there were only left for contest under the allegations of the bill the portions described in divisions two and three, before set out, to wit, the undivided twenty-two-sixtieths of thirty-nine and nine-tenths feet, lying next adjoining south of the said Kinney and Welton, as laid down on said diagram on Mason's base; and the undivided five and one-twentieth feet of the ten and one-tenth feet lying next south of the last abovenamed piece, on the same base, the said ten and one-tenth feet being the south ten and one-tenth feet of the fifty feet described in Kinney's said deed to Heydenfeldt as the “Kinney Mine.” The aggregate of said ten and one-tenth feet, thirty nine and nine-tenths feet, and ten and one-tenth feet, though differently divided, constitutes the twenty and one-tenth feet of the Kinney and Welton ground, and the fifty feet of the Kinney mine, as the same are described in the said deed from Kinney to. Heydenfeldt, making in all seventy and one-tenth feet. On June 10, 1859, Penrod & Co., since called Comstock & Co., of whom Comstock was one, while working on a claim made by them, discovered the Comstock lode. Before that time a number of claims had been taken up in the vicinity as square locations. On June 11, 1859, the following mining laws were adopted by the miners of Gold Hill district, which, at that time, embraced the Comstock lode:

“Article 1. There shall be elected one justice of the peace, one constable, and one recorder of this district, for the term of six months.”

616(Articles 2 and 3 define duties of justice of the peace and constable.)

“Art 4. The duty of the recorder shall be to keep in a well-bound book, a record of all mining claims that may be presented for record, with the names of the parties locating or purchasing; the number of feet, where situated, and the date of location or purchase; also, return a certificate for said claim or claims.”

(Sections 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 relate to the administration of civil and criminal law.)

“Sec. 7. Evidence of record of claims shall be considered title in preference to claims that are not recorded, nor shall the recorder record more than one hill, dry gulch or ravine claim, in the name of an individual, unless the same has been purchased.

“Sec. 8. All claims shall be properly defined by a stake at each end of the claim, with the number of members forming said company, and the number of feet owned.

“See. 9. All claims shall be worked, or the notice renewed in sixty days from the date of record, and no claim shall exceed two hundred feet square, hill claims excepted, which may be reduced to fifty feet front.

“Sec. 10. The recorder shall be allowed the sum of twenty-five cents for recording the claim of each individual or member of a company.

“Sec. 11. No Chinaman shall be allowed to hold a claim in this district.

“Sec. 12. This district shall include all the territory from the meridian of John Town to Steamboat Valley.

“Sec. 13. All quartz claims shall not exceed three hundred feet in length, including the depths and spurs.

“Sec. 14. Any person or persons discovering a quartz vein shall be entitled to an extra claim on all veins he or they may discover.

“Sec. 15. All persons holding quartz claims shall actually work to the amount of $15 to the share, within ninety days from the time of locating.

“Sec. 16. All persons holding quartz claims and complying with section 15, shall hold the same for the term of eighteen months as actual property.

“Sec. 17. All quartz claims shall be duly recorded within thirty days from the time of locating.

“Sec. 18. No person shall locate more than one claim on a vein discovered.

“Sec. 19. Any and all persons locating for mining purposes shall have the same duly recorded within ten days from the time of locating.

“Sec. 20. Resolved, that the above rules and regulations shall be signed by the citizens of this district, and all who may locate hereafter.

“J. A. Osborn was duly elected justice of the peace; Jas. F. Rogers, constable; V. A. Houseworth, recorder.

“A. G. Hammack, Chairman.

“V. A. Houseworth, Secretary.”

On September 14, 1859, the miners of Virginia district, embracing, at that time, the Comstock lode, adopted the following laws:

“Mining Laws of Virginia District.

“At a meeting of the miners of Virginia district, held at Virginia City, September 14, 1859, the following laws were adopted for the government of the miners of said district:

“Article 1. All quartz claims hereafter located shall be two hundred feet on the lead, including all its dips and angles.

“Art 2. All discoverers of new quartz veins shall be entitled to an additional claim for discovery.

“Art. 3. All claims shall be designated by stakes and notices at each corner.

“Art 4. All quartz claims shall be worked to the amount of $10, or three days' work per month to each claim, and the owner can work to the amount of $40 as soon after the location of the claim as he may elect, which amount being worked, shall exempt him from working on said claim for six months thereafter.

“Art. 5. All quartz claims shall be designated and known by a name and in sections.

“Art. 6. All claims shall be properly recorded within ten days from the time of location.

“Art 7. All claims recorded in the Gold Hill record and lying in Virginia district, shall be recorded free of charge in the record of Virginia district, upon the presentation of a certificate from the recorder of Gold Hill district, certifying that said claims have been duly recorded in said district; and said claims shall be recorded within thirty days after the passage of this article.”

(Article 8 stricken out by the meeting.)

“Art 9. Surface and hill claims shall be one hundred feet square, and be designated by stakes and notices at each corner.

“Art 10. All ravine and gulch claims shall be one hundred feet in length, and in width extend from bank to bank, and be designated by a stake and notice at each end.

“Art. 11. All claims shall be worked within ten days after water can be had sufficient to work said claims.

“Art 12. All ravine, gulch and surface claims shall be recorded within ten days after location.

“Art. 13. All claims not worked according to the laws of this district shall be forfeited, and subject to re-location.

“Art. 14. There shall be a recorder elected, to hold his office for the term of twelve months, who shall be entitled to the sum of fifty cents for each claim located and recorded.

“Art 15. The recorder shall keep a book with all the laws of this district written therein, which shall at all times be subject to the inspection of the miners of said district, and he is furthermore required to post in two conspicuous places a copy of the laws of said district.

“On motion, it was resolved that these laws be published in the Territorial Enterprise for one month.

617“Resolved, that W. O. Campbell be declared the recorder of this district.

“W. C. Campbell, Chairman.

“S. McFadden, Secretary.

“Virginia, September 14, 1839.”

Immediately after the discovery of the Comstock lode by Penrod or Comstock & Co-claims were located for a long distance north and south, the claimants taking the south stake of Penrod & Co.'s claim, since called the South Ophir stake, as the point of departure for their measurements, which stake has ever since been the recognized point of departure for the measurement of claims on the Comstock lode. Many, doubtless a majority of those who before had claims located as square locations, re-located their claims as ledge or lode locations under the said new mining laws adopted on June 11. Some others continued to claim, work and hold the ledge within the bounds of their claims under their old locations. Among these prior claimants one, Webb, had a claim purporting to be fifty feet front by four hundred feet deep, lying between two other claims; one on the north, now known as Central No. 2, and the other on the south, now the northern part of the White and Murphy. By whom originally, or in what precise manner located, does not distinctly appear. It seems, however, to have been a claim recognized by the miners of the vicinity.

On September 16, 1859, Webb conveyed to complainant, Kinney, one half of his said claim, by deed drawn by Kinney himself, in the following language:

“Joseph Webb to G. W. Kinney, Sept. 16, 1859.—Know all men by these presents, that I, Joseph Webb, for and in consideration of the sum of $200, paid to me as follows: a note for $150, in my favor, of even tenor and date with this article, payable three months after date, and signed Geo. W. Kinney, and $50 cash, the receipt of which I hereby acknowledge, have this day bargained and sold, and by these presents do bargain and sell to George W. Kinney, all of my right, title and interest in the undivided one-half of a mining claim of quartz, or surface mining, or any mineral the claim may contain. Said mining claim is situated at the town of Ophir, or Virginia City, Nevada territory, and is next adjoining the claim of Briggs, Cord & Co., on the south, and is five hundred and fifty feet distant from the mining claim known as the Comstock & Co. claim. Said mining claim is fifty feet in front, and runs back four hundred feet into the hill, all of which I warrant against any and all claims, the claim of the United States government alone excepted.

“In witness whereof I hereunto affix my hand and seal.

“Joseph his X mark. Webb. (L. S.)

“Signed and delivered in the presence of A. H. Hammack, Olive Penrod.

“Ophir, N. T., September 16, 1859.”

Two days after, on September 18, 1859, Webb conveyed the other half of his said claim to Jacobs and Weill, under the name of Jacobs & Co., by deed in the following language:

“Joseph Webb to H. Jacobs & Co. Know all men by these presents, that I, Joseph Webb have this eighteenth day of September, 1859, bargained, sold, conveyed and delivered unto H. Jacobs & Co. one undivided half interest in a certain quartz claim, containing fifty feet, situated and adjoining John Bishop on the north line, and the Murphy on the south, for and in the consideration of the sum of $200, paid in hand. Given under my hand and seal this date.

“Jos. his X mark. Webb.

“Attest: V. A. Houseworth, Chas. D. Daggett.”

Both said deeds were recorded. The said grantees of Webb took possession and worked on said claim in the manner and during the time as more fully stated in the opinion of the court. Whatever interest Jacobs and Weill had has become vested in defendants by various conveyances. And Kinney has made such conveyances as are mentioned in the opinion of the court; the interests so conveyed having also become vested in defendants by various conveyances.

On October 11, 1859, the following notice was recorded in the mining records of the district:

“Claim for Machinery and Right of Way. 1859, October 11. H. Jacobs and G. W. Kinney claim the ground lying in front of their claims. Commencing five hundred and fifty feet south of the Comstock claims, and running thence southerly along the line of a lead known as the Comstock lead, to the south line of Webb's claim. Said claim of ground for an outlet and machinery was made on the twenty-first day of September, 1859, as per posted notice of that date. William C. Campbell, Recorder.”

The testimony as to who caused this notice to be recorded is conflicting. Kinney denies that he had it recorded, while there is other testimony tending strongly to show that he did. The date of the claim, September 21, 1859, is the same as the date at which Kinney claims to have made a quartz claim of sixty feet yet to be mentioned. At the hearing it was claimed on the part of complainant that Jacobs & Weill's interest was only in a surface location; and that they had no interest whatever in the lode running through their claim; that subsequent to the said conveyances by Webb to Kinney and to Jacobs and Weill, Kinney discovered that there were sixty instead of fifty feet lying between the Central No. 2 and White and Murphy claims; that he located this sixty feet as a lode claim in his own name and for his own use. Upon that ground he claims to have owned the whole sixty feet In support of this claim

618

Kinney testified that he made such a location on September 21, 1859, by putting up stakes on each side, and a notice, the substance of which he recorded for the first time some four years afterward. One or two other witnesses testified that they saw on a stake what purported to be a notice of Kinney, but they could not remember its contents. Jacobs and Weill both testified that, although often on their claim, they never saw or heard of any such notice, and never heard that Kinney claimed sixty feet for himself alone or that he ever denied their right to one half of the fifty feet—that they never saw or heard of any notice of Kinney's except the machinery notice before set out. They admit that he claimed ten additional feet and wanted them to purchase half of that ten feet but they declined and denied the existence of an additional ten feet. Other witnesses who were in a position to be likely to have seen Kinney's notice testify that they never saw it And no witness except his attorney in a former suit testified to having heard of his claim to the whole. Kinney made no record of his notice at the time, but about four years after that, on July 18, 1864, Kinney had recorded in the mining records of the district the following:

“I claim and own sixty feet of this gold and silver bearing quartz lead, known as the Comstock lead, with all its dips, spurs and angles, commencing five hundred and fifty feet south from the claims of Comstock & Co., and running southward. George W. Kinney. Virginia City, Sept. 21, 1859.”

“Territory of Nevada, County of Storey, ss: This affiant, being first duly sworn, on his oath says, that on the twenty-first day of September, in the year 1859, he located sixty (60) feet of the gold and silver-bearing quartz lode, known as the Comstock lead, situated in what was then known as the Virginia mining district, Carson county, Utah territory; that he posted a notice on the mining ground, so as aforesaid located, which notice remained on the ground for several months, until destroyed by the rain and snow of the spring months of 1860, and that the accompanying writing is, in substance, a true copy of the aforesaid notice, and was made during the summer of the said year, 1860. George W. Kinney. Subscribed and sworn to before me, July 18, 1864. (Seal.) Geo. E. Brickett, Notary Public, Storey Co., U. T. (R. S., 5 cents.)

Subsequently one Welton became interested with Kinney in this mine, and upon remeasuring, he claimed to have ascertained that there were eleven feet more than sixty feet between the Central No. 2 and White and Murphy ground, and upon his suggestion, one Booth, on January 3, 1863, claimed this additional amount, which turned out to be ten and one-tenth feet He put up and recorded a notice which is as follows: “To all whom it may concern: You will please take notice that I, the undersigned, claim eleven (11) feet of the gold and silver-bearing quartz lode, known as the Comstock ledge, including all dips, spurs and angles belonging to the same, situated in this mining district, and between the ground of the White and Murphy Co., and the sixty (60) feet owned by the Kinney Co. Said eleven feet runs nearly north and south, or along the line of said lode, and is in width, or east and west, about three hundred (300) feet, or about one hundred and fifty feet each side of the center of Stuart street. George A. Booth. Virginia City, January 3, 1863. Filed and recorded January 3, 1863. Chas. H. Fish, Recorder.”

On the next day, January 4, 1863, Booth conveyed to Welton, without receiving any consideration, and afterward Welton conveyed one-half of said ten and one-tenth feet to Kinney. The fifty feet as the amount was originally supposed to be, the additional ten feet discovered and claimed by Kinney, and the further ten and one-tenth feet discovered by Welton, and claimed by Booth, making seventy and one-tenth feet. The difference in the amount depends upon the base adopted for the measurements, the end lines of mining claims on quartz lodes being drawn at right angles to the general course or strike of the lode. Taking the Freeman or defendants' base in the accompanying diagram (being the base of a right angled triangle formed by said line drawn from the South Ophir stake southward, the Mason or complainant's base drawn from the same point southward and westward, and the easterly line of the White and Murphy claim), as the course or strike of the lode, and measuring southward from said South Ophir stake on the said base of the triangle, there are but fifty feet between the Central No. 2 and White and Murphy claims, as claimed by defendants. But if the measurement from the same point is made on the hypothenuse of the triangle, or Mason base, there are seventy and one-tenth feet, as claimed by complainants. The complainants claimed at the hearing that the measurements should be made on the Mason base. Defendants claimed that they should be made on the Freeman base. Complainants further claimed that Kinney owned all except the half of the Booth claim of ten and one-tenth feet; that Jacobs and Weill owned none; and that all the conveyances made by Kinney should be charged to the north sixty feet as measured on the Mason base, and not to the whole seventy and one-tenth feet. These claims were controverted by defendants. On December 1, 1863, which was nearly a year after the said location of the Booth claim, a suit was commenced by Kinney's direction alone, in the name of himself, his several grantees and Jacobs and Weill, against the Central Company No. 2. The following being a copy of the complaint in the action, which was duly verified by Kinney:

620“Territory of Nevada, County of Storey. In District Court, First Judicial District.

“G. W. Kinney, E. W. Welton, J. M. Douglass, L. R. Mills, S. W. Dick, M. K. Truett, M. A. Wayman, Doc Wayman, H. Jacobs, Sol. Wiell, and R. Meacham, Plaintiffs, v. The Central No. 2 Gold and Silver Mining Company, Defendant.

“Now come the plaintiffs herein, by Barbour & Nougues, their attorneys, and complain of defendant, a corporation duly created, authorized and acting under and by virtue of the laws of the state of California, and for cause of complaint aver the following: That since the sixteenth day of September, A. D. 1859, they have been the owners, and in possession, and are now the owners and in the sole and exclusive possession of the following described mining ground and gold and silver-bearing quartz ledge; with all its dips, spurs and angles, and sufficient of the surface of the ground over and near thereto for its convenient working, situate in Virginia district, county and territory aforesaid, and more particularly described as follows, to wit: Commencing at a point five hundred and fifty (550) feet from the south line or stake of the Ophir Company's claim, on the Comstock lead, and running thence on the line of the said lead sixty (60) feet to the Booth claim, and known as the Kinney ground. Plaintiffs aver, that being so possessed as aforesaid, and in the quiet and peaceable enjoyment thereof, that they are informed and believe, and upon such information and belief charge the same to be true, that the defendant, through its officers and agents, unjustly and unlawfully, and without right, claim, or pretend to claim, some title or interest in and to the north twenty-one feet of said Kinney claim, and that the said wrongful and unlawful claim of defendant casts a cloud upon the title of the plaintiffs thereto, and causes great damages to the title and interest of the said plaintiffs to the above-mentioned and described premises, of sixty feet of said Comstock lead.

“Wherefore, the premises considered, plaintiffs pray that the claim and title of these plaintiffs to the said twenty-one feet of said mining ground may be confirmed by the judgment or decree of this honorable court. That the claim thereto of said defendant, and all persons claiming under it by title accruing subsequently to the commencement of this action, may, by such judgment or decree, be declared null and void, and that these plaintiffs may have and recover of said defendant their costs of this suit And these plaintiffs further pray for such other relief or further relief, or both, in the premises as they may be entitled to receive.

“Barbour & Nougues.

“Plaintiffs' Attorneys.”

On March 9, 1864, this action was dismissed as to J. M. Douglass, Sol. Wiell and H. Jacobs, who were plaintiffs. The suit went on as to the other plaintiffs. Afterward, on April 26, 1865, a judgment was entered in said case by consent of parties, and the judgment roll filed on said day, establishing the line between said parties at the northerly line of said Kinney and Welton ground, as drawn upon the accompanying diagram, at right angles to the Mason or complainant's base, as thereon laid down; and adjudging that the defendants in said action had no right, title or interest in any part of said mine lying to the southward of said line, and that the plaintiff therein had no right, title or interest in any portions of said mine lying to the northward of said line. Afterward, at the next succeeding term of said court, on June 27, 1865, without any further intermediate proceedings in said cause, a further judgment was entered in said cause, as follows, and a judgment roll thereof filed therein: G. W. Kinney and others v. Central No. 2 Gold and Silver Mining Company.

“The respective parties appearing in open court, and consenting thereto, it is hereby ordered, adjudged and decreed that the decree heretofore rendered in this case be so amended as to segregate and set apart to the plaintiffs, G. W. Kinney and E. W. Welton, twenty feet and one-tenth of a foot (20.1 feet) lying south of the division line established by said decree between the plaintiffs and defendant, and north of the line, as shown on said map attached to said decree and made a part thereof, running through the shaft marked ‘Kinney and Central No. 2 Shaft,’ which line runs parallel with the aforesaid division line; and it is further adjudged and decreed that the other plaintiffs have no right, title or interest in said twenty feet and one-tenth of a foot of ground; and that the ground lying south of said last-mentioned line shall remain the property of all the plaintiffs, according to their rights; but this decree shall not affect their rights as between themselves, but only as to the two division lines established by this and the original decree. It is hereby further ordered, adjudged and decreed, that the shaft marked on said map as the ‘Kinney and Central No. 2 Shaft,’ is the common property of the Kinney Company and the defendant, their respective interests to be determined by a settlement of accounts between the parties, as to the expenditures made by each in the sinking of the shaft Richard Rising, District Judge.” Indorsed: “1044. G. W. Kinney et al. v. Central No. 2 Co. Modified judgment. June 27, 1865.”

On May 3, 1875, pending the present action, Kinney conveyed to G. Frank Smith and A. J. Bryant, all the mining ground in the Virginia district, especially mentioning it as “known as the ‘Kinney Mine,’ and the ‘Kinney and Welton Mine,’” but without mentioning the Booth claim. On December 26, 1877, on leave granted, a supplemental bill was filed, alleging the said transfer 621of interest pendente lite, and asking that Smith and Bryant tie made parties; and that the same relief be granted as before prayed. The other facts necessary to explain the points decided are sufficiently stated in the opinion of the court The evidence, without headings and formal parts, covered over eight hundred closely printed pages.

G. Frank Smith, James T. Boyd, and S. W. Sanderson, for complainant.

C. J. Hillyer, R. S. Mesick, and S. M. Wilson, for defendants.

SAWYER, Circuit Judge (orally). Some time in the spring or summer of 1859, miners at work on the present site of the Comstock lead or lode, took up mining claims. About the tenth or eleventh of June, the Comstock Company struck the lode. Immediately thereafter locations were made, covering the entire lode for a long distance, north and south. Many locations had been made before. Among others which had been made before, was a location—in what way it was made is not very fully disclosed—by a party of the name of Webb, who claimed fifty feet front by four hundred feet deep. Other locations were made immediately after the discovery of the Comstock lode in the Ophir, the claimants commencing their measurements at the south Ophir stake and locating each way, north and south. Some locations overlapped each other. There were some contests about titles among the adjoining owners, in which Webb, who was an adjoining claimant was involved. In the final settlement, Webb's claim, whatever it was, was recognized as holding the lode. It originally purported to be a claim of fifty feet in front by four hundred feet in depth. Many of these locations were made in June, and immediately after the discovery of the lode in the present Ophir mine. Other locations had been made in the same form—square locations. Some of these parties relocated, others worked and continued on under their old locations, claiming and holding the lode thereby.

This Webb claim, down to September, was recognized by the adjoining claimants, notwithstanding the form of its location. There was some dispute between Webb and his adjoining neighbors. Some had overlapped and covered him. His claim, however, was finally recognized. On the sixteenth of September, he conveyed one-half to Kinney, the complainant in this case, and the form of the conveyance is this: “Have this day bargained and sold, and by these presents do bargain and sell, to George W. Kinney all of my right, title and interest in the undivided one half of a mining claim of quartz or surface mining or any mineral the claim may contain. Said mining claim is situated at the town of Ophir, or Virginia City, Nevada territory, and is next adjoining the claim of Briggs, Cord & Co., on the south.”

This deed, the testimony shows, was drawn by Kinney himself, and undoubtedly so drawn with the intent to cover everything that the location could be claimed to cover; quartz as well as other minerals, and any mineral that might be found in the lode as well as on the surface.

Two days after that Webb made another conveyance to Jacobs & Company, which consisted of Jacobs and Weill, and the conveyance is in this language: “Know all men by these presents that I, Jos. Webb, have this eighteenth day of September, 1859, bargained, sold, conveyed and delivered unto H. Jacobs & Co., one undivided half interest in a certain quartz claim containing fifty feet, situated and adjoining John Bishop on the north line and the Murphy on the south, for and in consideration of” and so forth.

In this deed he describes it as a quartz claim. Kinney, in drawing his own conveyance, not only uses the term “quartz” but the term “mineral,” doubtless, with intent to cover everything that could be claimed, so that it could be construed as covering a quartz claim. Whatever claim Webb had at this time was recognized by his neighbors, although some had located over him, on the ground that he had not located for a quartz claim; but afterward they recognized his claim. Although the claim is here called “fifty” feet, it is described as extending from Bishop (afterward Central No. 2.) on the north to the Murphy claim on the south.

Immediately after these conveyances made on the sixteenth and eighteenth of September, and more than three months after the Comstock lode had been discovered, and after the said lode had been all located as quartz claims, Kinney commenced a cut in this claim, and the testimony shows—and it is uncontradicted except by Kinney—that Jacobs paid him one-half of the money at the rate of $5 per day for the work. Afterward, Jacobs became dissatisfied with the amount of work that was done, and concluded to put a man in to work his share. He accordingly hired a man by the name of Brophy, and paid him $75 per month, and furnished him with provisions to go and work with Kinney. After working the cut for a while, they started a tunnel. The testimony is uncontradicted as to that. The testimony of Jacobs shows it; the testimony of Weill shows it; the testimony of Brophy shows it; the testimony of several of the complainants' witnesses shows it; and Kinney does not deny the fact of his working there. They commenced running a tunnel, ran in a considerable distance, and worked there until driven out by the snows and rains in the winter, some time in December. Jacobs and Weill paid Brophy, and Kinney worked himself in person. Jacobs and Weill complained even then that Kinney did not do half the work; that he was away a great deal, and did not work all the time. Afterward, an arrangement was made with the White and Murphy Company on the south, by which a shaft was to be sunk for the purpose 622of prospecting the lead for the benefit of both claims. They claimed a quartz lead. Jacobs and Weill had also an interest in that claim. An arrangement was made by which they were to jointly sink a shaft on the White and Murphy ground, for the purpose of prospecting this lead, and the agreement was to divide expenses between the White and Murphy and Kinney ground, as the Webb claim was then called. Jacobs and Weill were to pay on twenty-five feet in the Kinney, and nineteen feet and a fraction in the White and Murphy. Kinney also paid on his portion of the Kinney ground. That shaft was sunk for a considerable distance, and they worked at it along through 1860 and into 1861. That Jacobs and Weill paid their share is clear from the testimony. In fact it is uncontradicted, and there are contemporaneous bills introduced showing the fact, and showing the proportion which they paid, to be twenty-five feet in the Kinney, and nineteen and a fraction in the White and Murphy. There is one bill of Kinney's, also, which seems to have been made out in 1861, and about the close of their arrangements on that tunnel.

It was further testified by some of the witnesses—Skae, for instance—that Kinney paid on the twenty-five feet only. It was insisted, on the other side, that he paid on a larger amount. Kinney had claimed ten feet more, which he claimed to have found there. That one bill does indicate that he paid on thirty-five feet. The bill was made out by the White and Murphy Company to Kinney. Skae says it was, doubtless, because he claimed he had thirty-five feet, and it was made out in accordance with his wish and request. There is nothing to show whether the amount of that bill bears the ratio of thirty-five to twenty-five, or of twenty-five to twenty-five. He therefore only paid on thirty-five feet at most, while on his present theory he should have paid on sixty feet Jacobs and Weill paid on the remaining twenty-five feet. These facts, then, clearly stand out; that there was an arrangement by which Jacobs and Weill paid on twenty-five feet, and Kinney paid on the remaining twenty-five feet, and perhaps ten feet more. The whole of the other testimony, except his own, shows that Kinney only paid on twenty-five; but that one bill indicates that he paid on thirty-five, which would be one-half of the fifty feet, and the ten feet which he claims to have found and located outside of the fifty feet. There is that recognition from the beginning down so far, by Kinney, of the rights of Jacobs and Weill.

Coming down a little further, in the year 1862, another arrangement was made with the Central No. 2, by which the parties sunk a joint shaft also; and the agreement established by the testimony was, as I think, that this shaft should be sunk on the line between the Central No. 2 and the Kinney—one-half being on the Kinney side, and the other half on Central No. 2 side. They worked on until late in the year 1862 on that shaft and under that agreement. The agreement was to sink one hundred and fifty feet, in the ratio of one hundred feet to Central No. 2—the amount in that claim—and fifty feet to the Kinney Company, but they sunk more than that before they got through. There were drifts, also, from that shaft into the Kinney, and other drifts in other directions. The testimony of Jacobs and Weill is, that they entered into that arrangement and paid their share of the assessments, being on twenty-five feet. Kinney, in the meantime, had sold out portions of his ground; but Kinney and his associates paid on the remainder of the claim. There is quite a large number of contemporaneous receipts for moneys paid by Jacobs and Weill on this work. Receipt after receipt was introduced in evidence—contemporaneous receipts—which support the testimony of Jacobs and Weill, and others, in that matter. Those receipts are for money for assessments due on the Kinney ground, and signed “G. W. Kinney,” “George W. Kinney” and “Geo. W. Kinney,” secretary, purporting on their face to be for money for assessments upon the Kinney ground. That shaft was sunk for the purpose of developing the lead by the two companies. Kinney, in these transactions, purports to act as secretary; to have received the money and receipted for it, as secretary of the Kinney Company. These receipts for assessments continue down to late in 1862; so long, in fact, as there was really substantially any work done on this claim, except what was done by Jacobs and Weill, and somebody other than Kinney subsequently. There is one bill for labor, about which, doubtless, Weill is mistaken—the bill of Lynch. He testified that that was also on the work of the Central No. 2 tunnel. Lynch says he did not work on that tunnel, but in the White and Murpliy tunnel, and the bill shows by the date that it is for work done in 1861; so that Weill must be mistaken as to that work being done in Central No. 2. It was, doubtless, for work on the White and Murphy tunnel. Weill and Jacobs testify that they never knew, during this time, that Kinney repudiated their claim. They supposed that they were recognized as owning in company with him. The men who worked on the claim, and some of the complainants' own witnesses, say that they understood that Jacobs and Kinney were in company. Their neighbors so understood it. They sometimes bounded their deeds on the “Jacobs and Kinney claim.” Every one seems to have so understood it except Kinney, and there is no testimony except Kinney's—and his contemporaneous acts are against him—that he repudiated at that time the claim of Jacobs and Weill. On the conrary, Jacobs and Weill say that they did not know that Kinney denied their right. In 1863 there was a suit commenced by Wallace against the Kinney Company. In the 623meantime, Kinney had made a good many conveyances. That suit was commenced, and the very first defendants named are Weill and Jacobs, and then the various other defendants are named—parties to whom Kinney had, in the meantime, conveyed. The suit is against Sol. Weill, H. Jacobs, Doe. Wayman, Mrs. Wayman, John F. Dong, J. M. Douglass, M. K. Truett, Dick, Luther R. Mills and George W. Kinney. The first defendants named in the title of the suit are Weill and Jacobs. In that suit, Wayman, Long, Douglass, Truett, Dick, Mills and Kinney answered by themselves in a joint answer. They contented themselves with denying the title of the complainant. They answered by Barbour and Bryan & Foster as their attorneys.

In the same suit Weill and Jacobs answered separately, by their separate attorneys; they not only deny the title of the complainant, but allege that they are the owners of one undivided twenty-five feet in that ground. They defended in that suit, and they testified that they paid their counsel $2500 at first, as a counsel fee, and that they either paid them $1000 or $1500 subsequently as counsel fee. So they made a vigorous defense. When the suit came to trial, the plaintiff failed to make out his case, and he submitted to a nonsuit. A bill of costs was filed, and Jacobs and Weill's bill of costs is for $285. George W. Kinney's bill of costs, which he signs himself, is $123, so that it seems Jacobs and Weill sustained the brunt of that contest, and paid the larger portion of the expenses, and probably for the reason that Kinney had sold out so much of his twenty-five feet as to leave him with comparatively little interest. Soon after that suit was dismissed, in November, or a month or so, Wallace commenced another suit, and in that suit these several parties answer separately. Kinney answers separately, and in his answer in this suit he only claims five undivided feet. That explains the reason, doubtless, why Jacobs and Weill had the principal labor in this case—that Kinney's share had become small by prior sales. Now, the first answer Kinney verified himself in person. This answer is not verified. It is simply signed by his attorney; and it is said that this claim of only five feet is not an admission by him of the amount of his claim at that time, because he was not present, but his attorney, in his absence, put in this answer.

The summons was served on Kinney on November 20, and four days afterward, on November 24, his answer was filed; and he was there again very soon afterward, on December 1, when he commenced his own suit, as he verified his complaint on that day. So lie must have been in that neighborhood; and it is not at all likely that the answer was put in without his knowing it At all events, his attorneys were thoroughly conversant with his case, and had examined the records for other cases, as Nougues' testimony shows, and had examined them in relation to his ownership about that time. I merely throw this out as showing that at this late date, and after they had ceased the main work on these claims, Jacobs and Weill were recognized as owners of this claim by those who were suing the Kinney Company; that they appeared and defended, and really took the brunt of the defense on themselves, and Kinney must have been aware of it, as he was a party to the suit, and yet he says Jacobs and Weill never claimed that they had any interest in that lode. They paid a large amount of money for working and defending their claim, running through a period of more than three years. And here I will say, while I think of it, that in the White and Murphy claim the witness, Skae, who seems to have been one of the managing men, was asked by counsel what amount was spent on that tunnel; was the amount about $2000? And he said, “Yes, nearer $10,000.” Jacobs and Weill testified that they paid their share of the assessments of Central No. 2 and Kinney companies, amounting to from $1500 to $2000. And, as we have seen, they paid besides large counsel fees and expenses in defending their rights. Immediately after that, on December 1, 1863, also, after this work had been done, and while this second Wallace suit was pending, Kinney himself commenced an action against the Central Co. No. 2, and the plaintiffs therein are George W. Kinney, J. M. Douglass, L. R. Mills, S. W. Dick, M. K. Truett, M. A. Wayman, H. Jacobs, Sol. Weill and R. Meacham; but Kinney was the only man who had anything to do with commencing that suit. Nougues was then connected with Mr. Barbour as a law partner. Nougues, one of the attorneys, testifies that he knew nobody in that suit but Kinney; that Kinney represented Kinney and Welton, who were parties; that he had no interviews with anybody but Kinney, and brought the suit by Kinney's direction alone; that he had no consultation with any of the others; and he says Kinney then claimed that the others had no interest in that portion of the claim in dispute, being the northerly twenty-one feet, and this was a suit for twenty-one feet of the northerly portion of the lode, called the Kinney claim, the Booth claim being then called eleven feet Nougues says he made them parties because he found they were all interested, as he believed from an examination of the records. He made an abstract of it, which he showed Kinney. He says he had some discussion with Kinney; that Kinney objected to their being made parties, but he insisted on it. Finally, that he consented to dismissing the case as to Dougless, Jacobs and Weill. His recollection was, that he dismissed it as to all of these plaintiffs, except Kinney; but it turned out from an inspection of the order of dismissal, that 624it was only as against Douglass, Jacobs and Weill, the other complainants being left in. General Williams testified that this dismissal was on his application, and his clients were Douglass, Jacobs and Weill, and it was his only connection with the suit. He says he gave the notice himself, and a few days after the notice Kinney came to him and remonstrated with him personally, and insisted that it would not injure them, and that his clients should remain parties to the suit; that he declined, and Kinney was very much offended; and that he went in on the day when the motion was to be called up and made his motion, and there being no objection, the dismissal was had as to Jacobs, Douglass and Weill.

Now, I am satisfied on this point, that the recollection of General Williams is correct. I do not impugn the integrity of Mr. Nougues, but his recollection is defective. He testifies from his recollection, that the suit was dismissed by him as against all of them, except Kinney and Welton; that Kinney insisted that it should be dismissed as to all, and he supposed it was dismissed as to all. Now, it is not the fact that the suit was dismissed as to all the others. It was only dismissed as to Jacobs, Weill and Douglass, and these were all at that time General Williams' clients, because he answered for them in the suit commenced by Wallace a short time before. Williams could have no knowledge of it except being there on their behalf, as he had no other connection with the suit, and his recollections are that he went there, and it was dismissed, on his motion, as to his clients, and it was not in fact dismissed as to the others. So I think Nougues' recollection as to this point is mixed up with other matters, and somewhat at fault, and needs correction in this particular, as well as on the point that it was dismissed as to the whole. Williams testified that Kinney was dissatisfied, and came to him and remonstrated with him before he had the suit dismissed as to his clients, and was indignant at him for adhering to his purpose. This was as late as December—later, when this transaction of the dismissal took place. The suit was commenced in December. Soon after that Kinney left Virginia City. Weill testified that he employed a man by the name of Dougherty to sink the shaft twenty feet deeper. He testifies that he had spoken to Kinney about it, and Kinney said “Go ahead,” he would pay his share, but he never did pay it. He said Kinney manifested very little interest in it, as though he had but very little interest; and if he had but five feet, he had but very little interest. He said that Douglass paid, or his agent, Jones, paid for him on his part, so that he and Douglass paid all that was paid for the sinking of that shaft, and that was sometime subsequent to, or in. 1863. Kinney says after he went away, he understood that Douglass had done some work there. That would confirm Weill's testimony that Douglass and Weill had been working there during his absence. Weill again testified, and it is uncontradicted, that in 1868 he also entered into a contract with another man by the name of Simpson, by which he was to run a drift some seventy-five feet, and for his compensation, Simpson was to have such quartz as he should take out; and that he did take out quartz and work there in that way. There was no work done by Kinney subsequently to 1863, unless it was done by Judge Barbour. He says he believes Judge Barbour did some work to keep up his claim. Weill's testimony is uncontradicted on that point Taking his testimony as true, he and Jacobs were working from time to time down to 1868, and did the last work on that claim. Jacobs in the meantime sold out his claim—once sold out his entire interest in twenty-five feet—and sometime after, in 1866, he repurchased it. He must, then, at that time, have had confidence in the title.

Kinney, on the contrary, claims now, that he found by actual measurements, that there were ten feet more than had been supposed and at first claimed; and on the twenty-first of September, 1859, a few days after the purchase by him and Jacobs, that he put up a notice of a claim of sixty feet, measured it off, placed his stake, and stuck his notice upon it, claiming sixty feet. He claims that the work he was doing was on that claim, and that it was a quartz claim; that the work Jacobs and Weill were doing, not denying the fact of the work, was simply on a surface claim; that they were working together in the same tunnel and in the same cut with Kinney, with the White and Murphy, with the Central No. 2; all of whom were developing a quartz claim, except Jacobs and Weill; that Jacobs and Weill were paying their share of assessments in all these workings, and were developing nothing but a surface claim. Weill and Jacobs say that Kinney did claim an additional ten feet, and wanted them to take one-half, and they declined to buy it They insisted that there were no additional ten feet there, and that they were entitled to all the ground that there was between those two adjoining claims. Kinney now insists that he wanted to sell half of the whole sixty feet; but he says Jacobs and Well declined to buy it, because they had all that they wanted. Now “all they wanted” must have been either the twenty-five feet they were working and paying assessments on during those three years, or else what they had was that nineteen feet in the White and Murphy, or both. They may have referred to both or only to the Kinney ground, if any such remark was made. But they would be most likely to be talking of the claim in which they both owned. Kinney did not record his pretended notice of a claim for sixty feet. His notice was not recorded till within a month or two of four years after he claims to have taken the claim up. The mining laws, if he followed them, required him to record his notice within ten days. He never did record any notice, but 625only filed an affidavit stating that he had, on the twenty-first of September, 1859, put up a notice, and stated the substance of what he claimed it to be. This was in 1864, after they had ceased working on the claim, so far as the testimony indicates; that is doing any substantial work except what was done by Jacobs and Weill. One or two witnesses testified that they saw Kinney's stake, and saw a notice; but no one testified to the contents of that notice except Kinney. What the contents of that notice were, except from Kinney's own testimony, we do not know—whether he claimed it for himself, or for himself and Jacobs and Weill. At all events, Jacobs and Weill were working with him, by employing a man, and sharing the assessments; and though often on the ground, they say they never saw that notice. Kinney recognized them as owners, and collected assessments from them for working the mine, and that is against the theory that he claimed it all for himself. There was a notice for fifty feet in front of this claim for working purposes, filed soon after the purchase by Kinney and Jacobs, bearing date September 21, 1859, the same date that Kinney claims to have taken up his sixty feet, and that purported to claim the ground for working purposes, lying in front of the Jacobs and Kinney claim, and purported to be the notice of Jacobs and Kinney. A record of the notice was made October 11, 1859. The record is as follows: “H. Jacobs and G. W. Kinney claim the ground lying in front of their claims. Commencing five hundred and fifty feet south of the Comstock claim, and running thence southerly along the line of a lead known as the Comstock lead, to the south line of Webb's claim. Said claim of ground, for an outlet and machinery, was made on the twenty-first day of September, 1859, as per posted notice of that day.”

Jacobs says he never put that record there. Weill says he never put it there. They both say Kinney told them he did put it there; but Kinney says he did not put it there. Now it may well be that this is the notice that Kinney put up and which others saw, and which time and circumstances have, in Kinney's mind, transferred to a claim now set up of sixty feet on the lode. The same place would be a proper location for a stake and notice for either claim. Jacobs and Weill say they never saw any other.

The following is a resume of the facts substantially with reference to these claims, as shown by the evidence:

Webb, and, afterward, Kinney and Jacobs & Weill in company, were recognized by all their neighbors as holding that fifty feet of ground. They were recognized by their neighbors in their dealings with them, and by bounding on them in their deeds, by the name of Jacobs and Kinney. They were recognized as the owners in company by their employees. It was generally so understood. Kinney recognized Jacobs and Weill's ownership by working along with them during the three years, the entire time that those operations were being performed, and by collecting and receipting for assessments for working the mine. Kinney, in the suit which he brought, and to which I have already alluded, dated his title from the sixteenth day of September—the date of Webb's conveyance to him—and alleged that as the date of the inception of his title. Jacobs and Weill, by their employees, worked there as if they understood that they owned twenty-five feet; and Kinney acted as though he so understood it, and recognized them as working on the claim he was himself prospecting. Kinney worked personally some two or three months with Brophy, a man hired and paid by Jacobs and Weill. He received the money paid by them on the assessments levied to pay the expenses of working the claim, and signed the receipts as secretary of the Kinney Company. When anybody else brought a suit against the Kinney Company for the mine, they had no difficulty in bringing Jacobs and Weill in as defendants, and they seemed to take the laboring oar in the defense; and when Kinney himself brought a suit, he made them co-plaintiffs without consulting them, and afterward the suit was dismissed as to them, on motion of their own counsel, because they refused to go on with the proceedings. That this was originally what is called a square location, there is no doubt; and that other claims were located in the same way, worked in the same way, and held as lode claims in the same way, there can be no doubt. That appears from the testimony in the case, and has appeared frequently in other cases on the Comstock. It has become a matter of history—both judicial and general history. I do not know but that the court, under a recent decision of the supreme court, ought to take judicial notice of the general and judicial historical facts of the mode of locations on the Comstock lode. At all events the facts satisfactorily appear from the evidence, without resorting to the generally known historical facts. It is too late at this day to insist that Jacobs and Weill were not the owners of those twenty-five feet. In my judgment, no candid, disinterested, impartial mind, after a thorough examination of the testimony in this case, can entertain any greater doubt that Jacobs and Weill owned twenty-five feet of this claim in question, on the Comstock lode, than that Kinney himself owned any part of that claim. The testimony is just as satisfactory and conclusive, notwithstanding the fact that Kinney now repudiates the claim, that they owned twenty-five feet of that lead, as that Kinney owned any portion of it. I take it as settled by the testimony, beyond any reasonable controversy, that Jacobs and Weill owned twenty-five feet of that lead. Wherever, on a material point, the testimony of Jacobs and Weill differs from that of Kinney, I take the testimony of Jacobs and Weill rather than Kinney's 626because it is supported by the other testimony, and is in harmony with the general conceded facts, and such as we should expect from the condition of things and the intrinsic probabilities of the case, as developed by the testimony.