223

Case No. 7,653.

14FED.CAS.—15

KELLEHER et al. v. DARLING.

[3 Ban. & A. 438; 14 O. G. 673; 4 Cliff. 424.]1

Circuit Court, D. Maine.

Sept 21, 1878.

PATENTS—BOOT AND SHOE PACS—REISSUE—PROCESS OF MAKING AND THING MADE—PUBLICATION—PRIOR PATENT—ENTIRETY OF PATENT—DELAY IN APPLICATION FOR PATENT.

1. The reason of the rule that where a patent or publication is introduced in evidence to show that the complainant's invention had been patented or described in some printed publication prior to the supposed invention or discovery by the complainant the defendant will not be permitted to prove that the invention described in the alleged prior patent or printed publication was made prior to such patent or printed publication, explained.

2. The rule that where the complainant offers in evidence the patent in suit, accompanied by the application, the presumption is that the invention was made at the time the application was filed, but that the complainant may, if he can, introduce evidence to show it was made and reduced to practice at a much earlier date, discussed.

[Cited in Webster Loom Co. v. Higgins, Case No. 17,342; Eagleton Manuf'g Co. v. West, etc., Manuf'g Co., 2 Fed. 776.]

3. Where the alteration in a reissue consists in the addition of a distinct invention, there ought to be found in the original specification enough to fairly apprise other inventors and the public that the original invention included and embodied such additional feature.

[Cited in M'Kay v. Dibert 5 Fed. 592.]

4. The invention described in the original patent being in legal contemplation a new and useful manufacture, a reissue cannot include a claim for the process of manufacture, where in the original there was not a sufficient description for such process.

5. The rule that where the thing patented is an entirety, consisting of a machine or product, the respondent cannot escape the charge of infringement by alleging or proving that a part of the thing patented is found in one prior patent or machine, and another part in another prior patent or machine, and from the two or any greater number of such exhibits draw the conclusion that the patentee is not the original or first inventor of the improvement in question, considered.

[Cited in Burdett v. Estey, Case No. 2,146.]

6. Where more than one patent is included in one suit and more than one invention secured in the same patent the several defences authorized by the patent act may be pleaded to each patent in suit and to each invention included in the charge of infringement, but a defence addressed solely to one patent has no application to the other patents.

7. The principle of law that inventors may, if they can, keep their inventions secret, and, if they do, for any length of time, they do not forfeit their right to apply for a patent unless another in the meantime has made the invention and secured by patent the exclusive right to make, use, and vend the patented product explained.

8. The question whether it is sufficient, in order to defeat the right of the applicant to a patent, to show that his inventions had been in public use or on sale more than two years prior to his application, without proving that it was with his consent and allowance, considered.

9. The manner of pleading and proving special defences in suits for infringement discussed.

10. The nature of the special defences to patent suits considered.

11. The fourth claim of reissued patent No. 6,098, granted to P. Kelleher and J. C. Randlett, dated October 27, 1874, for moccasin boot-pacs, held void, as claiming new matter.

12. The first second, and third claims of said patent held valid, and infringed by the defendants.

13. The reissued patent No. 6,099, granted to P. Kelleher and J. C. Randlett, dated October 27, 1874, for moccasin shoe-pacs, held valid, and infringed by the defendants.

2 [This was a bill in equity [by Patrick Kelleher and James C. Randlett against Joseph O. Darling] founded upon two patents for improvements in the manufacture of moccasin boot and shoe pacs, and charging infringement of the same upon the respondent. [The original patent, No. 122,030, was granted to Kelleher and Randlett December 19, 1871, and reissued October 27, 1874, Nos. 6.098 and 6,099.]

[Wm. Henry Clifford, for complainants.

[As to the fourth claim of the reissue No. 6,098, it is claimed that this is for an invention other than that set out in the original. The claim is for the process that combines the so cutting the vamp, and so making the slit in the leg-front, that the length of the outline of the vamp is greater than that of the slit in the leg, and also dissimilar; then of so putting them together on a machine that the two outlines, of different lengths and shapes, shall coincide so as to produce the forcing out of leather and the crimp. Now, all of that was clearly seen from the original drawing and model, and the original patent. But the best way of doing it was 224not clearly shown or described. The thing to be done, and its results, were all as apparent as could well be. The inventors had omitted to clearly describe how, in one particular only, the thing was done. They amend their specification to give a full, clear, and exact description of that one omitted thing. As I understand it, that is the very purpose of a reissue. Such an inadvertence is exactly what the law allows an inventor to correct. No new invention is claimed in the reissue not seen clearly in the original patent and application. All that the reissue describes, not most clearly shown in the original application, is the turning of the parts under the needle of the machine, and on the plate of the machine, in the act of sewing. Now, the inventors show and describe how that may be done in the new patent. The rule governing the decision of this question is familiar. If it appears from the face of the papers that the invention described in the reissue is a different invention from that described in the original, then the commissioner, in granting the reissue, has exceeded his lawful authority, and his decision is not conclusive; otherwise, it is. But an inventor can supply omissions as to the manner of doing a thing which it is plain he did do.

[In conclusion, on this point we ask: (1) Is there any repugnance between the specification of the original and the reissue? (2) Is there any evidence that the reissue was fraudulently obtained? (3) In both the specifications, is not the invention manifestly for joining the described parts of a moccasin-boot; and as to the vamp and leg-front, is it not for doing it in a peculiar way, and under certain conditions? Is it a better description of those conditions or methods importing a new invention into the reissue? Or is it a better, more nearly full, and clear description of the same invention? Graham v. Mason [Case No. 5,671]; Carew v. Boston Elastic Fabric Co. [Id. 2,398]; Parham v. Buttonhole Co. [Id. 10,713]. The patent law provides for the new matter by saying, “Whenever any patent is inoperative or invalid, by reason of a defective or insufficient specification, * * * a new patent may issue in accordance with the corrected specification.” The patent office model shows the vamp sewed on to the leg-front with flat lap-seams. It shows the curvature or arch formed by the uniting of the two parts, and it shows the forcing out of the two parts to form the crimp or necessary curvature at the ankle and over the instep. The two parts are manifestly of different lengths and of dissimilar outlines. Their model and drawings showed that it was done, and fully exhibited the effects of its being done. Was there fraud? Is there apparent on the papers excess of authority on the part of the commissioner? Tucker v. Tucker Manuf'g Co. [Id. 14,227]. Is there a clear repugnance between the old and the new patent? House v. Young [Id. 6,738]. If neither, then the reissue is a valid one. If neither of these is shown, then the presumption is conclusive that the reissue covers only the inventions made prior to and intended to be patented under the first application. Hussey v. Bradley [Id. 6,946]; Potter v. Holland [Id. 11,329].

[William F. Seavey and Charles P. Stetson, for respondent

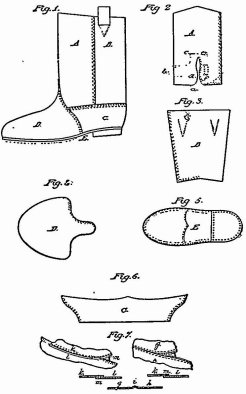

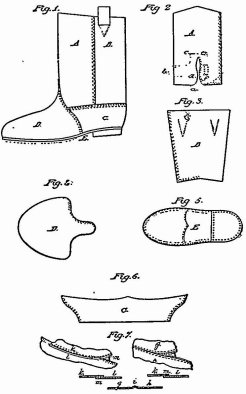

[One of the defences upon which respondent relies being that reissue No. 6,098 contains new matter, and is for a different invention from the original, it will be proper here to compare the two patents. The invention of complainants, as set forth in the original patent, is as follows: “The nature of our invention consists in so cutting the leather or material of which the pacs are manufactured, as to be able to do all the sewing of the upper parts by machinery instead of by hand, the latter being the method necessarily employed at present; and it also enables us to improve the shape, and to so change the position of some of the seams as to add very much to the durability of the pacs.” The figures of the drawing help materially to explain the nature of the invention.

[“In the accompanying drawing, Figure 1 is a boot pac made after our improved patterns, showing where the pieces are sewed together to form the complete boot pac. Figure 2 is the front of the leg. Figure 3 is the back of the leg. Figure 4 is the vamp of the boot-pac. Figure 5 is the sole. Figure 6 is the quarter of the boot pac.” The vamp is particularly described: “The vamp is different from all other vamps, in not having the sides run back to form part of the quarter; but the sides of this vamp pass directly across the foot simply obliquing a little toward the rear in passing down the sides of the foot thus simplifying the seams and making it possible to perform all the sewing by machinery.”

[The objects of the invention, and the means by which these objects are accomplished, are fully set forth, as follows: “The different parts of this boot and shoe pac are designed and arranged expressly with a view to enable all the seams to be closed by machinery, and dispense with hand-work altogether in the sewing, even to sewing on the soles; and for this purpose all the patterns have been simplified and the lap-seams adopted; and it is believed that there never was a pac made heretofore in which lap-seams were used exclusively, nor in which all the seams, even to sewing on the soles, could be accomplished by machinery; but by the use of these patterns and the lap-seams every seam may be closed on a machine, thereby reducing the cost of manufacturing very materially, and allowing the thick, heavy, and expensive leather to be used for soles, and the lighter and less expensive leather can be used for uppers.” Upon a careful examination of the specification, 225 it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the only invention described therein, or in any way indicated, consisted “in so cutting the leather or material” that the parts, when cut, could be united by the sewing-machine. The different parts were “designed and arranged expressly” for this purpose. All the patterns were “simplified I and the lap-seams adopted” with this end in view, and “by the use of these patterns and the lap-seams,” the result was to be accomplished. The reissue contains, in addition, what respondent insists is new matter, consisting of a long description of a process of stitching on the vamp or tip of a moccasin or boot pac, and a method of manipulating the tip while the stitching progresses, in such a manner as to form the “crimp.”

it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the only invention described therein, or in any way indicated, consisted “in so cutting the leather or material” that the parts, when cut, could be united by the sewing-machine. The different parts were “designed and arranged expressly” for this purpose. All the patterns were “simplified I and the lap-seams adopted” with this end in view, and “by the use of these patterns and the lap-seams,” the result was to be accomplished. The reissue contains, in addition, what respondent insists is new matter, consisting of a long description of a process of stitching on the vamp or tip of a moccasin or boot pac, and a method of manipulating the tip while the stitching progresses, in such a manner as to form the “crimp.”

[“The corner a of the tip D (see dotted lines in Figure 2) is first placed on the corner d of the front A, the tongue b of the tip, and also the tip itself, lying across the front A. We then start the sewing-machine and stitch, following along close to the edge a b of the tip D, at the same time turning the tip D on the front A until the end of the tongue b shall come around to e on the front and the stitches passing along the tongue b of the tip from a to b shall pass through the front A, following along from a to c, close to the edge, and operating in such a manner that when the stitching is completed from a to b of the tip, it shall also be completed from d to e of the front, and the two parts shall be stitched and crimped together from a to b of the tip, and from d to e of the front. The stitching is then continued along the tongue of the tip from b to c, and along the front from e to f, while the tongue is turned in the proper direction and the parts are stitched together so that the corner a of the tip is joined to the edge d of the front The end b of the tongue is then in its proper position at e on the tip, and the points a and c of the tip are in their respective positions at d and f on the front. The method of turning the tip while the process of stitching it on to the front progresses crimps the parts together and causes them to improve the shape of the moccasin.” Although this process was not hinted at in the original patent, it is described as essential and necessary in the reissue: “* * * But in order to admit of 226application of machinery to sew the seams of our moccasins together, we were obliged first to invent and construct the new patterns herein shown and described, and then, in order to join these new patterns together by machine sewing, we were compelled to devise a new method of sewing the tip on to the front of the moccasin, as described above.” Is it not apparent, by the admission of complainants themselves, that the reissue contains new matter? In the clause just quoted, they call the method used to join the “new patterns” a “new method,” and it certainly was not described in the original letters-patent.

[Upon this “new method” is founded a new claim, as follows: “The described process of smooth-crimping the instep of a pac or moccasin, consisting in cutting the tip D and front. A with edges of different lengths, and of dissimilar outlines, and bending, stretching, and compacting the edges in the act of sewing with a flat seam, so as to cause them to coincide under the needle, the joining of the differential edges displacing and forcing out the leather of the two parts in such manner as to form the crimp.” The drawings of No. 6,098 also contain new matter, not found in the drawing of the original patent, Figure 2 of the original having, in the reissue, an additional figure in dotted lines, marked D, purporting to show complainants' vamp or tip as placed on the leg of the boot, preparatory to beginning the process of stitching, as described in the reissue. But upon comparing this new figure with the figure of the vamp described in the original patent and shown in Figure 4, the difference between the two is apparent. It appears, then, that the new process described and claimed in the reissue 6,098, is a new process for uniting the old patterns of a moccasin boot. The first defence relates particularly to reissue No. 6,098, and is founded on the provisions of section 4916 of the Revised Statutes of the United States. This section provides that, upon certain conditions therein set forth, the commissioner of patents shall have the power to receive the surrender of a defective patent and cause a new patent to issue for the same invention. This power is further limited by the provision that “no new matter shall be introduced into the specification,” “nor shall the model or drawings be amended, except each by the other.” “Whether the reissue patent is for the same invention as the original, and whether or not it contains new matter, are questions to be determined by the court, upon a comparison of the two instruments.

[Respondent claims that, in this case, the provisions of the statute have been disregarded in three particulars, viz.: (1) That the reissue is for a different invention than that described in the original patent. (2) That new matter, not suggested or substantially indicated in any part of the original patent, has been introduced Into the reissue. (3) That the drawings of the reissue have been amended by introducing a new figure, found neither in the original drawing nor in any way entering into the construction of the model originally filed. The claims covered an article of manufacture, a moccasin boot-pac formed of these patterns. The original patent was for an alleged new manufacture. The reissue is for a process or method.

[This invention, beginning with an improved moccasin, changes into a new method of crimping a moccasin. Complainants say in the reissue, “but in order to admit of the application of machinery to sew the seams of our moccasins together, we were obliged first to invent and construct the new patterns herein shown and described.” This they did, and these new patterns were claimed in the original patent of 1871. But then, “in order to join these new patterns together by machine sewing, we were compelled to devise a new method of sewing the tip on to the front of the moccasin, as described above.” In view of the peculiarly suggestive language of these paragraphs, and the fact that the first intimation of any “new method” appears in the reissue, is it not fair to infer that the new patterns were invented at the date of the original application, while the “new method” remained in embryo until the application for reissue? Everything indicates that this new method was an afterthought. In the original application, they allege that they enable the pac to be made by machinery by the use of these new patterns. In the reissue, they admit that, in order to sew these “new patterns” together, they were compelled to devise a “new method,” and in describing this “new method” they do not describe how it is to be applied to their “new patterns;” but by means of a new figure show how it is to be used upon the old moccasin tip. The fact that new matter has been introduced into the reisue, and that the drawing has been amended, contrary to the statute, seems too apparent to require argument. Gill v. Wells [22 Wall. (89 U. S.) 1]; Russell v. Dodge [93 U. S. 460].

[Reissue No. 6,098. Respondent submits: (1) That reissue No. 6,098 is not for the same invention as the original, and is void. (2) That, if valid, no infringement of the first, second, and third claims has been proven. (3) That complainants were not the first inventors of the subject-matter covered by the second claim, but that the same was patented to Ware & Tilton, January 7, 1868. (4) That complainants were not the first inventors of the process covered by the fourth claim; it being the same process used long previous in the manufacture of tongue or opera boots, of serge and leather, and in the hand-sewed moccasin. (5) That the only change made by complainants was the substitution of one well-known seam for another, and that such substitution does not constitute 227a patentable invention. Reissue No. 6,099: (1) That no infringement of any of the claims of this reissue has been proven. (2) That the evidence shows only that respondent manufactured the old and well-known “brogan” shoe or pac, which he had a right to do. It is submitted that, for the reasons assigned, complainants have shown no right under their bill.]3

CLIFFORD, Circuit Justice. Persons sued as infringers in an action at law may plead the general issue, and, having given the required notice in writing thirty days before, may prove, on trial, the special matters set forth in the act of congress, of which the following are material to be noticed in the present case: (1) That the invention had been patented or described in some printed publication prior to the supposed invention or discovery. (2) That the patentee was not the original and first inventor or discoverer of any material or substantial part of the thing patented. (3) That the invention had been in public use or on sale in this country for more than two years before his application for a patent, or that it had been abandoned to the public. Rev. St. § 4920.

Notices of the kind must be in writing, and must be given thirty days before the trial; and, if the defence is prior invention, knowledge, or use of the thing patented, the requirement is that it shall state the names of the patentees and the dates of their patents, and when granted, and the names and residences of the persons alleged to have invented, or to have had the prior knowledge of the thing patented, and where and by whom it had been used. Like defences may be pleaded in equity for relief against Infringement, and proofs of the same may be given upon like notice in the answer. Proof to sustain the first defence is sufficient, if the patent introduced for the purpose, whether foreign or domestic, was duly issued, or the complete description of the invention was published in some printed publication prior to the supposed invention or discovery, and the patent or printed publication will be held to be prior if it is of prior date to the patent in suit, unless the patent in suit is accompanied by the application for the same, or unless the plaintiff or complainant, as the case may be, introduces parol proof to show that the invention was actually made prior to the date of the patent or prior to the time the application was filed. Neither the defendant nor respondent can be permitted to prove that the invention described in the alleged prior patent, or the invention described in the printed publication, was made prior to the date of such patent or printed publication, for the reason that the patent or publication can only have the effect as evidence that is given to them by the act of congress. Unlike that, the presumption in respect to the invention described in the patent in suit is, if it is accompanied by the application, that it was made at the time the application was filed, and the plaintiff or complainant may, if he can, introduce evidence to show that it was made and reduced to practice at a much earlier date.

Two reissued patents are the subject of the present suit, both of which are of the same date, and were obtained upon the surrender of an original patent previously issued to the same patentees for certain alleged new and useful improvements in the manufacture of moccasin boots and shoes, or boot and shoe pacs, as particularly described in the original specification. The power of the commissioner to cause a new patent for the same invention to issue, in case the original is surrendered, is not questioned; nor is it denied that he, in his discretion, may cause several patents to be issued for distinct and separate parts of the thing patented, upon demand of the applicant, and upon payment of the required fee for each reissue. Rev. St p. 959, § 4916. Separate examination will be given to each patent, though certain, parts of the specification in each are the same, having been borrowed from the original. As described in the original and in each of the reissues, the invention consists in so cutting the leather or material of which the pacs are manufactured as to be able to do all the sewing of the upper parts by machinery, instead of by hand,—the latter being the method necessarily employed at present,—and it also enables the operator to improve the shape, and to so change the position of some of the seams as to add very much to the durability of the pacs. Detailed description is then given, in the specification of the reissued patent for the moccasin boots or boot-pac, of the several pieces of which the pac is composed, by special reference to certain figures in the reissued drawings, and in the exact words and figures contained in the original drawings. Appended to that is the description of the manner in which the leg of the boot-pac and the quarter and vamp are cut, the same being given in the same words as in the surrendered patent, from which it appears that the leg of the boot-pac is made in two pieces, that the quarter is formed in one piece crossing and passing forward of the seam in the leg and joining directly on to the vamp, and that the vamp is also stitched to the front part of the leg, all the seams being flat seams, which may be closed by sewing-machines. Every step in the process of cutting and stitching the parts together having been described, the patentee proceeds to state that the different parts are designed and arranged expressly with a view to enable all the seams to be closed by machinery, and to dispense with hand-work altogether in the sewing, even to sewing on the soles, and that for that purpose all the patterns have been simplified so as to admit of lap-seams; and he expresses the belief that there never was a pac 228made before in which lap-seams were exclusively used, nor in which all the seams, even to sewing on the soles, could be accomplished by machinery, which, as he states, reduces the cost of manufacture very materially, and allows the use of heavy material, for soles, and lighter and less expensive material for uppers. Both of the things patented are called “pacs,” from the manner in which they are used. They are made of a peculiar kind of leather called “moccasin” leather, and are cut large, to admit of packing between the inside of the upper leather and the foot of the wearer. Boots and shoes are usually made to fit the foot; but the moccasin-pac, whether boot or shoe, is made much larger than the foot of the wearer, in order that it may contain the desired amount of packing for protection to the foot in extreme cold weather.

Coming first to the reissue 6,098, which is the moccasin-boot, and which contains four claims, to the effect following: (1) For a moccasin boot or shoe pac formed of five parts, cut as shown and described, and joined together by flat lapped seams. (2) For a moccasin boot or pac with the leg formed of two flat pieces cut as shown and described, and united by two lapped seams, one on each side of the leg, as shown and described. (3) For the quarter of a moccasin-pac cut in the form shown and described, and formed into one piece, for the use as specified. (4) For the described process of smooth-crimping the instep of a pac or moccasin, consisting in cutting the tip and front with edges of different lengths, and of dissimilar outlines, and bending, stretching, and compacting the edges, in the act of sewing with a flat seam, so as to cause them to coincide under the needle, the joining of the differential edges displacing and forcing out the leather of the two parts in such a manner as to form the crimp.

Service was made, and the respondent appeared and filed an answer, in respect to the first patent, setting up, in substance and effect, the following defences: First. That the reissued patent, 6,098, embraces and includes, both in the specification and claims, new matter, not described, suggested, or indicated in the specification of the original patent, nor shown in the drawings or patent office model. Second. That the invention described in the specification of the patent, and claimed in the second claim, was patented to the persons named in the answer prior to the supposed invention by the complainants. Third. That the patentees are not the original and first inventors of such part of the invention as is described in the specification, and claimed in the second claim of the patent, or any material or substantial part of that which is therein described. Fourth. That so much of said invention as is so described and claimed in the second claim of the patent was in public use and on sale more than two years prior to the supposed invention by the complainants. Fifth. That the patentees were not the original and first inventors of any material or substantial part of the invention claimed in the fourth claim of the patent, but that the same was known to and in public use by the persons named in the answer prior to the supposed invention by the patentees. Sixth. That he has never infringed the first three claims of the patent.

The first defence, which is that the feature of the invention claimed in the fourth claim was not described nor indicated or suggested in the original specification, nor shown in the drawings or patent office model, finds support both in the specification and fourth claim of the reissued patent under consideration. Extended argument to sustain that defence is quite unnecessary, as it is scarcely possible to imagine what could be added to the description of the process of producing the crimp in the moccasin-boot, to render it more specific and intelligible than it now is, as incorporated into the specification of the reissued patent, nor is any argument necessary to show that every word of the description is new matter, not found in the specification of the original patent, as that is apparent from a comparison of the two instruments. Corresponding addition is also made to the drawings, showing conclusively that the solicitor who applied for the new patent did not deem the drawings of the old patent sufficient to illustrate the new feature added to the invention in the descriptive portion of the reissued specification.

Suggestions of an ingenious character are made in behalf of the complainants to show that an expert, in attempting to unite the described parts of the patented product by the lap-seam, might discover the means of bending, stretching, and compacting the edges of the parts in the act of sewing, so as to cause them to coincide under the needle, as stated in the amended specification, and that by the joining of the differential edges the leather of the two parts would be displaced and forced out in such a manner as to form the crimp shown in the new figure of the drawings; but the patent law, in terms, requires more than that of the patentee before he is entitled to a patent. Before any inventor shall receive a patent for his invention, he shall make application therefor in writing, and shall file in the patent office a written description of the same, and of the manner and process of making, constructing, compounding, and using it, in such full, clear, concise, and exact terms as to enable any person skilled in the art or science to which it appertains to make, construct, compound, and use the same. Rev. St. p. 934, § 4888. Apply that rule to the original patent, and it is clear that, if the fourth claim of the reissued patent had been inserted in the original patent, it could not have been sustained for the want of a compliance with that important requirement of the patent act. Cases arise, undoubtedly, where a suggestion in the 229specification, or an indication in the drawings or patent office model of the original patent, may be sufficient to justify an alteration or enlargement of the description of the invention in the specification of a reissued patent, as where the change consists merely in the substitution of a different material from that of which a device is composed, or in the modification in the form of a device, or in the proportions of the ingredients; but where the alteration consists of a distinct invention, there ought to be found in the original specification enough to fairly apprise other inventors and the public that the invention includes and embodies such additional feature. Seymour v. Osborne, 11 Wall. [78 U. S.] 544. Interpolations of new features, ingredients, or devices which were neither described, suggested, nor indicated in the original patent or patent office model, are not allowed in the reissued patent, as it is clear that the commissioner has no jurisdiction to grant a reissue unless it be for the same invention as that included and embodied in the original patent, nor can any new matter be properly introduced into the specification, nor the patent office model or drawings, in a machine patent, be amended, except each by the other. Rev. St. p. 959, § 4916.

Beyond doubt the invention described in the original patent, though composed of the several parts therein described, is, in legal contemplation, a new and useful manufacture, and it is equally clear that the process of making an article of manufacture is a different invention from that of the product. Both may be included in the same patent, but the required description is as essential and indispensable in the one case as in the other. Viewed in the light of these suggestions, the court is of the opinion that the fourth claim of the reissued patent is void. Patents, in certain cases, may be good in part and void in part, the rule being that whenever a patentee, through inadvertence, accident, or mistake, and without any fraudulent or deceptive intention, has claimed more than that of which he was the original and first inventor or discoverer, his patent shall be valid for all that part which is truly and justly his own, provided the same is a material or substantial part of the thing patented. Rev. St § 4917; Goodyear v. Providence Rubber Co. [Case No. 5,583].

Special consideration must also be given to the second and third defences set up in the answer, as the attempt of the respondent in those two defences is to show that the matter claimed in the second claim of the patent in suit was patented to others prior to the supposed invention by the complainants, and that the patentees are not the original and first inventors of any material or substantial part of what is claimed in that claim. Such defences, if well pleaded to the invention described in the patent, would be good defences, as the act of congress provides that the defendant in a suit at law may plead the general issue, and, having complied with the requirement as to notice, may give such special matters in evidence, and the provision is that if any one or more of the special matters alleged shall be found for the defendant, judgment shall be rendered for him with costs. Like defences may be pleaded in equity under like conditions, the allegation in the answer denying infringement supplying the place of the general issue in an action at law. Under that pleading and notice, the respondent in an equity suit may prove that the invention described in the patent in suit had been patented or described in some printed publication prior to the supposed invention by the patentee. Documentary evidence is required to sustain that defence, but, as before remarked, the evidence is sufficient if the patent introduced for the purpose, whether foreign or domestic, was duly issued prior to the alleged invention described in the complainant's patent, or if the complete description of the invention was previously published in some printed publication. Evidence of the kind must be held to be prior in point of time in all cases where the patent or printed publication precedes the date of the patent in suit, unless the patent in suit is accompanied by the application for the same, or unless the complainant introduces parol proof to show that his invention was made prior to the date of the patent, or prior to the time the application was filed.

Proof of the kind is not admissible, on the part of the respondent, to show that the invention described in the supposed prior patent or printed publication was made prior to their respective dates, for the reason already stated. Under the second and third defences, as pleaded, the rule is that the patent in suit affords the complainants a prima facie presumption that the patentees are the original and first inventors of that which is therein described as their improvement Competent proof is requisite to overcome that presumption, as, for example, that the thing patented had been previously patented to another, or that it had been previously described in some printed publication, or that the patentees are not the original and first inventors of the patented improvement, or of any material or substantial part of the same. Where the thing patented is an entirety, consisting of a machine or product, the respondent cannot escape the charge of infringement by alleging or proving that a part of the thing patented is found in one prior patent or machine, and another part in another prior patent or machine, and from the two or any greater number of such exhibits draw the conclusion that the patentee is not the original and first inventor of the improvement in question. Instead of that, his plea, which in the action at law is the general issue, is addressed to the entire charge of infringement, which casts the burden to 230prove, that charge upon the plaintiff or upon the complainant in the suit in equity.

Infringement is the charge made by the party seeking redress, and it is competent beyond all doubt for the defending party to show that he does not infringe at all, or that his machine, product, or manufacture infringes only a part of the claims of the patent in suit. Authority for that proposition is found in the very nature of the issue between the parties, but the only authority for attacking the originality and validity of the patent is that given by the patent act. Defences for that purpose must be addressed to the thing patented, and not merely to one of the separate features which it comprises. More than one patent may be included in one suit, and more than one invention may be secured in the same patent, in which cases the several defences authorized by the patent act may be pleaded to each patent in suit and to each invention included in the charge of infringement. Gill v. Wells, 22 Wall. [89 U. S.] 24.

Combination patents may be mentioned as examples where more than one invention may be secured in a single patent, and in such a case the patentee may give the description of each combination in one specification, and in that event he can secure the full benefit to each of the inventions by separate claims, referring back to the proper description in the specification. Cases of the kind often arise, and in such a case the party charged with infringement may plead and prove, if he can, the statute defences to each invention, just as if the two inventions had been embodied in separate patents. Ample support to that proposition is found in the language of the patent act and in the practice of the courts, but where the patent describes an entire invention as a machine, manufacture, or product, the defences specially authorized by the act of congress must be addressed to the thing patented, and the evidence introduced to sustain the plea or defence must show that the thing patented had been previously patented to another, or that it had been previously described in some printed publication, or that the patentee was not the original and first inventor of the improvement, to entitle the defendant or respondent to a judgment or decree. Parol proof is sufficient for that purpose, if it shows that the thing patented was actually made and reduced to practice prior to the patented invention. Models made and used merely as experiments, and which were not capable of use as operative machines, cannot affect the right of a patentee holding a patent issued in due form. Seymour v. Osborne, 11 Wall. [78 U. S.] 539. Incomplete attempts to construct a machine amount to nothing as evidence to support such a defence, but if the evidence shows that it was complete and operative, even for a temporary use, and that its existence and use were within the knowledge of a few persons, it may be sufficient to establish the proposition that the thing patented was made and used by another prior to the patented invention. Coffin v. Ogden, 18 Wall. [85 U. S.] 120.

Inventors may, if they can, keep their inventions secret, and if they do for any length of time they do not forfeit their right to apply for a patent unless another in the mean time has made the invention, and secured by patent the exclusive right to make, use, and vend the patented product. Within that rule, and subject to that condition, inventors may delay to apply for a patent, but the patent act provides that the defendant or respondent in a suit for infringement may plead the general issue, and, having given the required notice, may prove in defence that the patented invention had been in public use or on sale more than two years before the alleged inventor filed his application for a patent, and the provision in that event also is that if the issue be found for the party setting up that defence, the judgment or decree shall be in his favor. Different phraseology was employed in the prior patent act, which made it necessary for the party setting up such a defence to prove that the invention had been in public use or on sale with the consent and allowance of the patentee before his application for a patent. Decided cases adjudicated under that act and certain earlier acts, show that a very limited public use or sale of the invention with the consent and allowance of the patentee, if prior to his application for a patent, was sufficient to defeat the right of the inventor to the protection of the patent act. Pennock v. Dialogue, 2 Pet. [27 U. S.] 19; Whitney v. Emmet [Case No. 17,583]; Ryan v. Goodwin [Id. 12,186]; Wyeth v. Stone, [Id. 18,107]. Congress, however, interfered, and provided that no patent shall be held to be invalid by means of such purchase, sale, or use prior to the application for a patent as aforesaid, except on proof of abandonment of such invention to the public, or that such purchase, sale, or prior use has been for more than two years prior to such application. 5 Stat. 354. Public use or sale, even under that provision, which was in the nature of an amendment to the earlier patent act, in order to defeat the right of the inventor to a patent, must have been for the period mentioned with his consent and allowance. Pierson v. Eagle Screw Co. [Case No. 11,156].

Unlike that, the present patent act provides that the defending party, having given the requisite notice, may prove that the invention had been in public use or on sale, in this country, for more than two years before the inventor applied for a patent, and that if that special matter is found in his favor he is entitled to the judgment or decree with costs. Construed in view of these suggestions, the better opinion is that the provision in the present patent act is in the nature of a statute of limitations, and that it is sufficient to defeat the right of the applicant to a patent if it be shown that his invention 231had been in public use or on sale more than two years prior to his application, without proving that it was with his consent and allowance.

Due proof of prior invention and practical use by another is sufficient to defeat the right of the applicant for a patent, because it shows that he is not the original and first inventor of the alleged improvement, even if the prior invention was only made and used for a day, if it clearly appears that it was operative, and that it was actually reduced to practice, the rule being one of actual priority as defined by the rules of law and evidence. None of these principles are controverted by the parties in this case, but the defence of prior public use or sale stands upon a different footing, and depends upon widely different proofs. As before remarked, the inventor may, if he can, keep his invention secret, and, if he does, no length of delay will debar his right to apply for a patent; but if he fails to keep it secret, and it goes into public use or is on sale for more than two years before he applies for a patent, he forfeits all right to the same, and the person sued as an infringer may, if he gives the proper notice, plead that special matter in defence, and, if he proves it, the judgment or decree must be in his favor. In the former case the gist of the defence is that the invention was first made and reduced to practice by another, but in the latter the gist of the defence is that the invention, though made by the applicant for the patent, went into public use or was on sale more than two years before the inventor filed his application for a patent Nothing of the kind is pleaded in the answer, nor is there any proof in the record to support the proposition, if it had been well pleaded. Reliance for that purpose in pleading is placed upon that feature of the answer in which it is alleged that so much of the invention as is claimed in the second claim of the patent was in public use or on sale more than two years prior to the supposed invention by the complainants. Sufficient has already been remarked to show that such a defence is unwarranted by the act of congress, which authorizes the defendant or respondent to plead the general issue to the declaration or bill of complaint, and, having complied with the condition as to notice, to give in evidence the special matters enumerated in the same section of the patent act.

Patentees seeking redress for the infringement of their patent must, undoubtedly, allege and prove that they are the original and first inventors of the improvement, and that the same has been infringed by the party against whom the suit is brought. In the first place, the burden to establish both of those allegations is upon the party instituting the suit; but the law is well settled that the patent in suit, if introduced in evidence, affords the moving party a prima facie presumption that the first allegation is true, and has the effect to shift the burden of proving the defence upon the defending party. Blanchard v. Putnam, 8 Wall. [75 U. S.] 420; Seymour v. Osborne, 11 Wall. [78 U. S.] 538.

Where the requisite statute defences are well pleaded, the defending party may give evidence to overcome that presumption; but if he does not plead and prove those defences, or some one of them, the prima facie presumption is sufficient to entitle the moving party to a judgment or decree. Suppose the rule were otherwise, and that evidence may be admitted, though the defence is not pleaded to show that the invention had been in public use or on sale more than two years before the complainants filed their application for a patent, still the concession would not benefit the respondent in the case before the court as the record contains no evidence whatever that the invention made by the complainants was ever in public use or on sale, even for a day prior to their application for a patent; nor does the respondent set up any such theory, even in argument His proposition, in contemplation of law, is altogether different What he contends is that the invention was made by others prior to the supposed invention by the complainants, and that the prior invention made by others was in public use or on sale more than two years before the complainants applied for their patent Knowledge of the complainants' invention was never acquired by the public before they filed their application; nor is there the slightest proof in the record that the invention which they made ever went into public use, or was ever on sale, even in a single instance, before their application for a patent was filed. Even meritorious inventors must keep their inventions secret unless they apply for a patent within two years; and if they do not, and their invention goes into public use, or is on sale in this country for more than that period before they file their application, the invention is forfeited to the public, whether it was in such public use or on sale with or without their consent and allowance; and plea and proof of such special matter is a good defence for one charged with infringement. Infringers may also plead and prove that the patentee of the patent in suit was not the original and first inventor of the improvement in question; and they may prove the issue by showing that the invention; had been previously patented by another, or that it had been previously described in some printed publication, or that it had been previously made and actually reduced to practice before the invention was made by the patentee. Such proofs may be introduced, and, if they sustain the defence pleaded, the judgment or decree must be for the defending party. These issues, however, are very different from the one raised by the defence, that the invention had been in public use or on sale in this country more than two years before the patentee filed his application for a patent, as the latter defence still involves an element of laches on the part of the patentee, 232in that he did not file his application for a patent at an earlier date, or keep his invention a secret from the public.

All the remarks made in respect to the fourth defense, as herein arranged, apply with equal force to the fifth defence, which is also overruled for the same reasons. Where none of the defences pleaded are sustained, the prima facie presumption that the patentee is the original and first inventor of the improvement must prevail; and the patent in this case must accordingly be adjudged valid, Infringement being denied, the burden of proof is upon the complainants to establish the charge. Where the invention is embodied in a machine, manufacture, or product, the question of infringement—which is a question of fact—is ordinarily best determined by a comparison of the exhibit made by the respondent with the mechanism described in the complainants' patent. Comparisons of the kind have been carefully made by the court in this case, and the court is of the opinion that the respondent has infringed the first, second, and third claims of the complainants' patent for the boot-pac. Both parties gave evidence upon the subject; but the great weight of the proofs supports the affirmative of the charge. Strong support to that view is also derived from the answer, in which the respondent admits that he has made 4.491 pairs of boot-moccasins, in which the lips and fronts were cut with edges of different lengths and dissimilar outlines, and were united by sewing with a flat seam, substantially as set forth in the fourth claim of the patent, the difficulty being to see how that could well be done without infringing the other three claims of the patent. Without entering further into the details of the evidence, suffice it to say that the court has carefully examined and compared the several exhibits in view of all evidence introduced, and is of the opinion, without hesitation, that the respondent has infringed the first three claims of the patent.

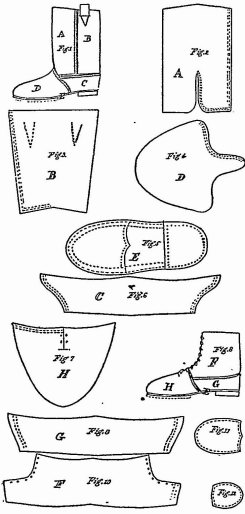

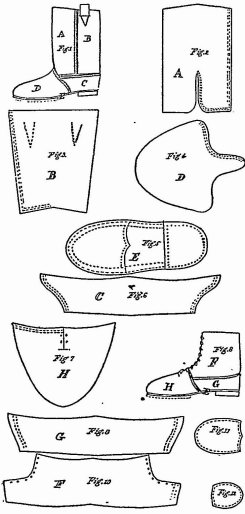

Reissued letters-patent of the same date were also issued to the complainants for new and useful improvements in the manufacture of moccasin-shoes, or shoe-pacs, including some of the elements embodied in the patent previously described; and the specification states that the nature of the invention consists in the same peculiarities as those described in the specification of the prior-named patent. Special reference is also made to the drawings annexed to the specification for a description of the various parts of which the invention is composed, to illustrate the relative positions of the several parts of the invention; and the patentees state that there is a free selection of stock in respect to the service each part is designed to sustain when they are put together; and he adds that the principal benefit is found in the fact that the seams can be made flat and be stitched by machinery, thus avoiding all hand-work. By the specification it also appears that the quarter is formed in one piece, and that it joins directly on to the vamp, and forms a flat seam, both at its junction with the top and with the vamp, allowing both of those seams to be stitched by machinery; and the specification also shows that the vamp is stitched to the other three parts of the thing patented by similar flat lap-seams, thus allowing them all to be closed by the sewing-machine, and without hand-work, in sewing the parts together; and the patentees further state that the different parts of the shoe-pac, as patented, are designed and arranged expressly with a view to enable all the seams to be closed by machinery, and to dispense with hand-work altogether in sewing, even to the sewing on of the soles, thereby reducing the cost of manufacturing the article very materially, and enabling the shoe-pacs to be made more rapidly, economically, and with less expense of material. Three claims are appended: (1) For a moccasin shoe-pac, formed of four parts, cut as shown and described. (2) For a shoe-pac with a quarter cut in the form shown in the third figure of the drawings, made in one piece, to surround the heel and extend forward to the vamp, as specified. (3) For the combination in a shoe-pac of the four parts shown and described when united together by flat lap-seams.

Plenary authority is given to the defending party, by the patent act, to plead the general issue in a suit for infringement; and, if he complies with the requirement as to notice, he may introduce evidence, and prove any one or more of the special matters specified in that act; and, if he proves one or more of them, he is entitled to prevail in the suit; but, if he does not give the required notice, he has no right to introduce such evidence; and the moving party, in that event, if he introduced his patent in evidence, is entitled to the benefit of the prima facie presumption that he is the original and first inventor of the patented improvement. Agawam Woolen Co. v. Jordan, 7 Wall. [74 U. S.] 596; Blanchard v. Putnam, 8 Wall. [75 U. S.] 427. Separate answers in respect to each patent might have been filed by the respondent, or he might elect to state all his defences in each case in one answer, without waiving any of his legal right; but, in the latter case, the defences addressed solely to the patent for the boot-pac have no application to the patent for the shoe-pac. Argument to support that proposition is unnecessary, as the statement of the same is sufficient to secure universal assent. Tested by that rule, it is clear that the only defence set up in the second case is the denial of infringement.

Suffice it to say that the complainants, having introduced their patent in evidence, must, under the circumstances, be presumed to be the original and first inventors of the patented improvement inasmuch as there is neither plea nor proof to the contrary. Neither plea nor proof appearing in the record to overcome the prima facie presumption in favor 233of the complainants, the decree must be that the patent is valid, if the proofs are sufficient to establish the charge of infringement. Questions of infringement are questions of fact, in respect to which the parties are chiefly interested in the court's conclusions; and, in that view, it is not usually deemed necessary to enter much into the details of the evidence, as that would extend the opinion of the court to an unreasonable length. Due comparison of the exhibits has been made in this case, and the court is clearly of the opinion that the charge of infringement is fully proved.

Decree for complainants upon both patents for an account of gains and profits to the extent of the infringement, and for an injunction to the same extent.

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.

it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the only invention described therein, or in any way indicated, consisted “in so cutting the leather or material” that the parts, when cut, could be united by the sewing-machine. The different parts were “designed and arranged expressly” for this purpose. All the patterns were “simplified I and the lap-seams adopted” with this end in view, and “by the use of these patterns and the lap-seams,” the result was to be accomplished. The reissue contains, in addition, what respondent insists is new matter, consisting of a long description of a process of stitching on the vamp or tip of a moccasin or boot pac, and a method of manipulating the tip while the stitching progresses, in such a manner as to form the “crimp.”

it is impossible to avoid the conclusion that the only invention described therein, or in any way indicated, consisted “in so cutting the leather or material” that the parts, when cut, could be united by the sewing-machine. The different parts were “designed and arranged expressly” for this purpose. All the patterns were “simplified I and the lap-seams adopted” with this end in view, and “by the use of these patterns and the lap-seams,” the result was to be accomplished. The reissue contains, in addition, what respondent insists is new matter, consisting of a long description of a process of stitching on the vamp or tip of a moccasin or boot pac, and a method of manipulating the tip while the stitching progresses, in such a manner as to form the “crimp.”