Case No. 7,365.

JOHNSEN v. FASSMAN et al.

[1 Woods, 138; 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 471: 2 O. G. 94.]1

Circuit Court, D. Louisiana.

April 6, 1871.

PATENTS—APPLICATION AND ISSUE—ABANDONMENT.

1. The fact of abandonment must result from the intention of the patentee expressly declared or clearly indicated by his acts.

2. The issue of letters patent by the patent office is prima facie evidence that there has been no voluntary abandonment of his invention to the public by the inventor, either before or after his application for letters patent

3. The rule to be deduced from the authorities on the question of abandonment after application is, that after the issue of letters patent, the abandonment must be shown to be positive, actual and intentional by some act or declaration of the inventor, or by such gross laches as indicate unmistakably an intention to abandon the invention to the public.

4. Where nothing was relied upon to defeat complainant's patent but the inventor's delay in prosecuting his application for the patent, his application having been finally rejected by the commissioner, April 11, 1857. and not appealed until August 16, 1866, during four years of which time the patent office was closed to him by reason of his residence in a state that was in rebellion, held, that no direct or implied abandonment was shown.

[Cited in Colgate v. Western Union Telegraph Co., Case No. 2,995.]

5. A patent relates back to the date of the application; and patents granted to other inventors during the pendency of such application, so far as they cover the same invention, are void, and are no protection to an infringer.

[Cited in Goodyear Vulcanite Co. v. Willis, Case No. 5,603; American Roll-Paper Co. v. Knopp, 44 Fed. 611.]

6. A cotton-bale tie, in which the lower edges of the transverse slots are provided with lips or flanges projecting downward at an angle with the plane of the buckle, to prevent the end of the band from slipping, held to be infringed by a tie in which the slots are provided with toothed or serrated edges for the same purpose.

[Final hearing on pleadings and proofs. Suit brought upon letters patent [No. 59,144] for an “improvement in cotton-bale ties,” granted to complainant [Charles G. Johnsen], as assignee of Charles Swett, October 23 1866. The nature of the patented invention and of the alleged infringement are set forth in the opinion.

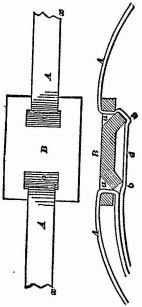

[The above engraving represents the Swett tie in plan and in section. The end of the band, A, is passed through the slot, a, and bent backward. The other end, having passed around the bale, is thrust through the other slot, and under the projections, b, b, as shown at d; so that when the bale expands, as it is released from the press, the band is tightly gripped between the tie and the bale, or between the bale and the upper part of the band, and thus held securely. An illustration of the “alligator,” or defendant's tie, will be found in the report of the ease of Cook v. Ernest [Case No. 3,155].2

A. Phillips, C. Roselius and S. S. Fisher, for complainant.

Lea, Finney & Miller, for defendants.

WOODS, Circuit Judge. This cause is submitted for final decree upon the pleadings and evidence. The object of the suit is to enjoin defendants from infringing upon an improvement in cotton-bale ties, which the complainant avers was patented to Charles Swett, October 23, 1866, and by whom all rights under said patent have been assigned to complainant. The claim of Swett's patent was for “a new and improved fastening block for securing metallic bands or hoops to cotton-bales,” described thus: “A block of suitable size, either made by casting or stamping out of metal. In this block are formed two slots or holes parallel with each other across the block; the length of the slots is to be equal to the width of the hoops to be used. From the corner and inner edges of the slots, projections extend out obliquely beneath said slots and nearly covering their lower openings.” After applying the bands as described in the specification, “then, when 717the bale is removed from the press, the elasticity of the cotton presses firmly against the ends of the hoops and prevents them being withdrawn.”

The answers of defendants allege, by way of defense, that long before the date of the patent of Swett and of his assignment to complainant, Swett had abandoned his invention. They aver that the application of Swett for letters patent was made in the year 1856, and was rejected in the same year, and again, upon an amendment of specifications, was finally rejected by the commissioner of patents, April 11, 1857, for want of novelty; that Swett acquiesced in the decision of the commissioner from that date until August, 1866; that from the date of the rejection of his application in April, 1857, down to August, 1866, Swett took no steps whatever to obtain letters patent for his said invention, but acquiesced entirely in the rejection of his application, and abandoned his pretension to a patentable invention; and that in the meantime many different forms of blocks, plates and buckles with slots for the insertion of a hoop or band, and various devices to hold and fasten the ends of the bands together, with the aid of the expansive pressure of the cotton in the bale, were in notorious use; that on April 18, 1865, letters patent, embodying those general features, were issued to defendant E. Victor Fassman, and were reissued on an amended specification on December 11, 1866, relating back, however, to the said April 18, 1865. They allege that an appeal to the supreme court of the District of Columbia was taken by Swett; but aver that it was not until the year 1866, long after the application of Swett had been abandoned, and that the effect of the decree of that court was merely to overrule the decision of the commissioner of patents, rejecting said application for want of novelty.

The answer also denies any infringement of the complainant's patent by the defendants, or any of them, so that the only questions presented by the pleadings are: (1) Did Swett abandon his invention before the issue of his letters patent? and (2) have the defendants infringed? The facts as to the delay between the application of Swett, April 23, 1856, and the issue of letters patent to him, October 23, 1866, are correctly stated in the answer. Defendants rely upon these facts as proof of abandonment, and offer no other evidence. There is no proof of actual abandonment. Are these facts sufficient evidence to support the defense of abandonment? The fact of abandonment must result from the intention of the patentee expressly declared or clearly indicated by his acts. In the case of Adams v. Jones [Case No. 57], Mr. Justice Grier said: “By the application filed in the patent office the inventor makes a full disclosure of his invention, and gives public notice of his claim for a patent. It is conclusive evidence that the inventor does not intend to abandon it to the public. The delays afterward interposed, either by the mistakes of the public officers or the delays of courts, where gross laches cannot be imputed to the applicant, cannot affect his right.” In the case of Dental Vulcanite Co. v. Wetherbee [Id. 3,810], Mr. Justice Clifford says: “The next objection to be noticed is that the inventor abandoned his invention, because his application for a patent was made April 12, 1855; was rejected February 6, 1856; and because he did not appeal at all or make any new application until March 25, 1864. Actual abandonment is not satisfactorily proved, and it is not possible to hold that any use of the invention, without the consent of the inventor, while his application for a patent was pending in the patent office, can defeat the operation of the letters patent after they are duly granted. Such delays are sufficiently onerous to a meritorious inventor, if his patent is allowed to have full operation after it is granted; but it would be very great injustice to hold that any delay, which the inventor could not prevent should, under any circumstances, affect the validity of his patent.” So in the case of Rich v. Lippincott [Id. 11,758], Mr. Justice Grier charged the jury as follows: “If you find that the application in 1836, renewed in 1837, was for the same subject matter now patented, and if such application was not withdrawn by Fitzgerald, but the delay was caused by the conduct of the commissioner of patents in refusing to grant the patent for the same invention since patented, then Fitzgerald should not be considered to have abandoned his invention to the public, unless he abandoned it before 1836, which is not contended.” In this case the patent was issued in 1843. In McMillin v. Barclay [Id. 8,902], the question is asked: “Upon what reasoning should the inventor be regarded as having given up his invention to the public, merely because a public officer has repeatedly denied his application for a patent and the recognition of his right has thus been denied for years, when he was powerless to prevent it?” The issue of the letters patent by the patent office is prima facie evidence that there has been no voluntary abandonment of his invention to the public by the inventor, either before or after his application for letters patent.

The rule to be deduced from the authorities on the question of abandonment after application for letters patent we think to be this, that after the issue of letters patent, the abandonment must be shown to be positive, actual and intentional by some act or declaration by the inventor, or by such gross laches as indicate unmistakably an intention to abandon the invention to the public. Nothing is relied on in this case but the delay of the inventor in taking his appeal from the decision of the commissioner of patents to the supreme court of the district. The application of Swett was finally rejected, 718on amended specifications, April 11, 1857. He appealed on August 16, 1866. Here was a delay of nine years and four months. In the case of Dental Vulcanite Co. v. Wetherbee, supra, there was an interval of eight years between the rejection by the patent office and the appeal. That was not considered by the distinguished judge who decided that case as sufficient evidence of abandonment. But in the case on trial, if we were disposed to hold that a delay of nine years and over was sufficient evidence of abandonment unless accounted for, there is a fact disclosed by the record which would relieve Swett of the imputation of gross laches—that is, that he was a citizen of one of the states in revolt during the late rebellion—to wit, the state of Mississippi—so that for four of the nine years of the interval between the rejection of his application and his appeal, the patent office was closed to him. Bearing this fact in mind, we are clear that no direct or implied abandonment is shown by the record in this case. The fact that, between the date of the application of Swett and the issue of his letters patent, other letters patent were issued to other inventors for substantially the same invention, gives them no right to infringe on Swett's patent. His patent relates back to the date of his application; any patent for the same invention granted to another inventor, while his previous application was pending, so far as it covers Swett's invention, is void, and is no protection to an infringer.

The next and only other question presented for determination is the question of infringement. An inspection of the models of the buckles used by the defendants clearly shows that they all embody the principle and infringe on the Swett patent. The only tie about which I have had any doubt is known as the alligator tie. This tie consists in a buckle, the opening or slot of which has serrated or toothed edges, which, when the pressure is removed from the bale, prevents the slipping of the end of the tie. There are no lips or flanges turned down at an angle with the plane of the buckle, as in the Swett patent. The serrated edges in the alligator tie are substituted for the flange in the Swett tie. The application of Swett was first rejected by the patent office on the ground of want of novelty—the commissioner deciding that it was substantially identical in form and effect with the common sliding clasps or buckles used on hat bands, suspenders, harness, etc. Sir. Chief Justice Carter, in his opinion reversing the decision of the commissioner, says: “Inspection of the device satisfies my judgment that this conclusion is erroneous. The contrivance is neither buckle nor sliding clasp, although performing more or less the office of each, and for the purpose designed, more effectual than either. The clasp and buckle are both without the flanges that constitute the distinguishing excellence, enabling it to hold the contents of the bale by the very process exerted in escape. It embraces, also, the advantage undisclosed in either clasp or buckle—viz.: tying itself up to its work through the agency of force exerted against it, a function employed by neither clasp nor buckle. The teeth in the alligator tie perform the same function as the flanges in the Swett tie, and on the same principle, viz.: “they hold the contents of the bale by the very process exerted in escape; it ties itself up to its work through the agency of force exerted against it.” It is the same device acting on the same principle, performing the same function, only modified in form. We think it to be an infringement on the Swett patent, now the property of complainant. Let there be a decree for complainant, enjoining defendants as prayed in the bill, and let the case be referred to a master to take an account of profits.

[Patent No. 59,144 was reissued May 7, 1872 (No. 4,896). For another case involving this patent, see Johnson v. Beard, Case No. 7,371.]

1 [Reported by Hon. William B. Woods, Circuit Judge, and by Samuel S. Fisher, Esq., and here compiled and reprinted by permission. The syllabus and opinion are from 1 Woods, 138, and the statement is from 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 471]

2 [From 5 Fish. Pat. Cas. 471.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.