Case No. 5,605.

GORDON v. ANTHONY et al.

[16 Blatchf. 234: 4 Ban. & A. 248; 16 O. G. 1135.]1

Circuit Court, S. D. New York.

May 3, 1879.

PATENTS—PHOTOGRAPHIC SHIELD—INFRINGEMENT—BILL BROUGHT AFTER EXPIRATION OF PATENT—ACCOUNT OF PROFITS—BILL OF DISCOVERY—ASSIGNMENT OF PATENT BY RECEIVER.

1. The letters patent granted to Ebenezer Gordon, October 19th, 1858, for “a photographic shield,” are valid.

2. Although a suit in equity for the infringement of a patent is brought after the patent has expired, and no injunction can be granted, and the bill is not a bill of discovery, the court has jurisdiction to award an account of profits, and can take cognizance of the suit.

[Cited in Atwood v. Portland Co., 10 Fed. 284; Consolidated Oil Well Packer Co. v. Eaton, Cole & Burnham Co., 12 Fed. 870.]

[Cited in Carver v. Peck, 131 Mass. 294.]

3. A bill without interrogatories, under the amendment to rule 40 in equity, made at the December term, 1850, and which prays only for a disclosure of gains and profits from infringement, is not a bill of discovery.

4. The case of Stevens v. Gladding, 17 How. [58 U. S.] 455, examined and explained.

7735. An assignment of an interest in a patent, made by a receiver, appointed by a state court, of the property of the owner of the patent, conveys no title to the assignee, because the assignment is not a written instrument, signed by the owner of the patent.

[Cited in Secombe v. Campbell, 5 Fed. 806; Ager v. Murray, 105 U. S. 131; Adams v. Howard, 22 Fed. 658.]

[Disapproved in Wilson v. Martin-Wilson Automatic Fire Alarm Co., 151 Mass. 520, 24 N. E. 780.]

[Bill by Ebenezer Gordon against Edward Anthony and others for the alleged infringement of a patent]

Starr & Ruggles, for plaintiff.

Charles F. Blake, for defendants.

BLATCHFORD, Circuit Judge. This is a bill in equity founded on letters patent [No. 21,829] granted to the plaintiff, October 19th, 1858, for 14 years from that day, for a “photographic shield.” The bill was filed in 1873, after the patent had expired. The patent had, in fact, been extended, but the bill does not allege any extension, as the right for the extended term had been assigned by the plaintiff. The bill alleges the unlawful manufacture and sale by the defendants, ever since January 1st, 1864, of photographic apparatus containing the patented improvement. It alleges that the defendants had derived and received therefrom gains and profits to about the sum of $20,000, and prays that the defendants be required “to make a disclosure of all such gains and profits.” It also prays that the defendants be compelled to account for and pay over to the plaintiff all such gains and profits, and, in addition, to pay damages, and for an injunction to restrain the infringement of the patent by the defendants. There are no interrogatories to the bill.

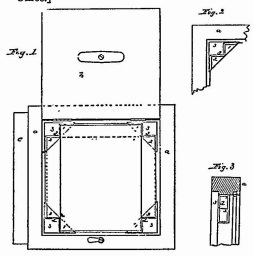

The specification of the patent sets forth that the invention is an “improvement in frames or shields for photographic cameras.”

[Drawings of Patent No. 21,829, Published from the Records of the United States Patent Office.]

Drawings are annexed. It says: “Fig. 1 is a view of the frame or shield with the back open, to show my improvements; Fig. 2 is a view of one corner; and Fig. 3 is a section through the frame, representing one of my improved corner pieces in place. Similar marks of reference denote the same parts. In taking landscape views, groups and similar pictures, the plate is used in a horizontal position, while in taking likenesses of one person, and similar views, the longest side of the plate receiving the same stands vertical in the camera. To accommodate these two positions in photographic and similar pictures, separate frames have been constructed to receive and shield the plate while being conveyed to and from the camera, or else the camera has to be turned upon its side, greatly to the inconvenience of the operator, and the loss of time in adapting the plate and camera to take the particular picture. My said invention obviates all the foregoing inconveniences, and consists in what may be termed a ‘turn shield,’ the same being a frame a, adapted to the camera, with the back b, and slide c, in the usual manner. The interior of this frame forms a square opening, of a little more than the longest length of the plate to be used therein; d, d, are my improved corners, that are formed of suitable material, and each corner piece has two recesses for receiving the glass or other plate, the recesses 1, 1, sustaining the same when the longest sides of the plate are vertical, and the recesses 2, 2, receiving the plate when in position for a landscape or similar picture. Between the recesses 1 and 2, in each corner there is, therefore, a square block or support, 3, measuring along its side, one-half the difference between the vertical and horizontal sides of the glass or other plate, which, with the present sizes of plates, will be ½ an inch, one inch, or one and a half inches, for the square of the said block, 3. The frames carrying smaller sizes of plates, adapted to the main frame or shield in the usual manner, can be placed into the corners aforesaid, in either a vertical or horizontal position, and the plate will occupy a corresponding position within said frames.” The claim is: “The corners, d, d, formed with two recesses, and applied at the angles of a square frame, to receive the photographic plate, or its equivalent, in a horizontal or vertical position, as set forth.”

The record contains the following admission: “Counsel for defendants admits that the defendants, before the filing of the bill and since the date of the letters patent herein, have made and sold corner pieces of which Exhibit A is a sample; and, also, that they have sold, within the said period of time, corner pieces of which Exhibit B is a sample; and that such corners were used and applied at the angles of square frames, used to receive and hold photographic plates in photographic cameras, which frames containing said corners were also made and sold 774by the defendants, as aforesaid; and that the frame of which Exhibit C is a sample is a frame of the kind made and sold by them containing corner pieces like said Exhibits A and B.” It is not claimed that what was so done by the defendants was not a practicing of the invention claimed in the patent, although no witness testifies that it was. There is no admission, however, that what was so done by the defendants was done before the 19th of October, 1872, when the patent expired. It may have been done after that date and yet have been done “before the filing of the bill and since the date of the patent.” Both parties, however, have proceeded on the view that it was done before the patent expired.

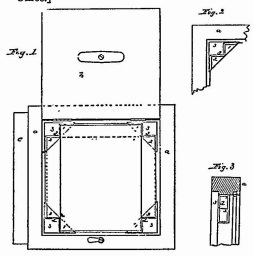

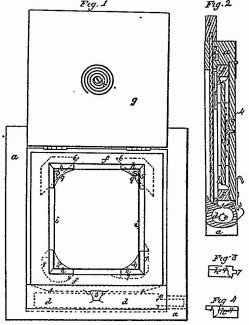

The defendants attack the plaintiff's patent for want of novelty, and several prior inventions are adduced. One is a patent granted to M. J. Drummond, assignee of William Lewis and William H. Lewis, the inventors, October 7th, 1856 [No. 15,854], for a “plate holder for photographic cameras.” The specification of that patent points out two matters as requiring remedy in taking photographs—one, that, immediately after the plate is taken out of the nitrate of silver bath, it is placed in the frame for the camera, and the liquid drops off into the frame, and, in handling, runs on to clothes, or carpet, or floor, and stains; the other, that the moist collodion and chemical substances on the corners of the plate adhere to the edges of the frame and rebate and prevent the plate coming properly into focus, while such dirt and chemical matter also stains the chemicals on the plate, being often absorbed so

[Drawings of Patent No. 15,854, Published from the Records of the United States Patent Office.]

as to become a blemish on the background. The specification states, that the nature of the invention consists in “the use of glass or similar vitrified corners in the frame that receives the corner of the glass or other plate, the said corners each being formed of one solid piece of vitrified material, so that there is no chance for the chemicals to come in contact with any material that will cause discoloration.” It further says: “We also introduce a receptacle into the bottom of the frame or holder, that catches any drippings from the plate and retains the same, even if the holder is laid down on its side.” The receptacle is not material. The glass corners are thus described: “h, h are solid corners of glass or other vitrified material, secured into the angles of the frame f, and, as these corners may be attached by different means, we have shown at 5, 5, small screws passing through holes in said corner pieces, into diagonal pieces, 6, 6, attached to the frame, and, over the head of said screws suitable cement is placed, but the same must be below the surface of the glass corners. At 8, 8, we have shown a flanch formed on the back of the glass corner, receiving screws that pass into the frame f. We are aware that pieces of glass have been inserted in the corners of plate frames, to take the face of the glass or other plate, but said pieces of glass are very apt to become loose. The cementing made use of comes in contact with the corners and edges of the glass or other plate, and discolors the same, and there is no chance for keeping the corners clean. In view of the foregoing, the nature and utility of our invention will be apparent, for, the solid glass or vitrified corner can always be kept clean, and there is nothing that comes in contact with either the surface or the edges of the glass or other plate, but the said vitrified corners. At 9, 9, small projections are shown on these vitrified corners, which, being slightly elevated, always take the plate, and are wiped off with greater ease, so as to ensure a proper focal position for the plate.” The patent claims: “Forming the glass or vitrified corners, h, with a flanch or rim, in one solid piece, the said flanch or rim taking the edges of the photographic glass or other plate, substantially as and for the purposes specified, and irrespective of the manner in which the said vitrified corners are attached to the frame.” The testimony of William Lewis, one of said inventors, shows that he made and sold as early as 1856 square plate holders with the glass corners of the Drummond patent. Mr. Hicks, the defendants' expert, states that he considers the substance of the invention set forth in the plaintiff's patent to be “a photographic frame, having corners in the corners of the photographic frame, provided with recesses, and the whole, when complete, enabling the operator to reverse from a vertical to a horizontal position an oblong photographic plate, so that it shall be held, whether reversed or vertical, in three 775directions—endwise, both up and down; facewise, which prevents it from passing through the frame; and sidewise, which prevents it from moving laterally.” He further says: “I find in the invention of Lewis, referring to his testimony, and taking it in connection with his patent, substantially a photographic frame provided with glass corners, the frame being made square, so that the plate may be reversed from a vertical to a horizontal position, and provided with elevations on the face of the glass corners, so located in reference to the frame, that a photographic plate could be placed in said frame and held vertically between said elevations, which would prevent the plate from moving sidewise, the face of the plate preventing it from pushing through, or, in other words, supporting the face of the plate, and the flanges of the corners preventing endwise movement of the plate. When the plate is turned in a horizontal position, the same stops operate upon the photographic plate in the same manner as before described as to the vertical position of the plate. I, therefore, find in the invention of Lewis, the substance of the invention set forth in the Gordon patent. The difference which I wish to notice between these two inventions is, that, in the Lewis invention referred to, as set forth in his testimony, a square plate may be used, resting upon the glass studs to which I have referred before in this answer, and which are marked 9 in the Lewis patent, and probably were intended to act against the face of a square plate, to locate its focal distance, instead of the face of the corner, which would thus act, if the plate were placed between the studs.” Professor Charles A. Seeley, the plaintiff's expert, testifies as follows: “The Lewis invention consists of solid glass corners for a camera shield. Previous to the Lewis invention the corners were usually made of pieces of glass cemented together. For such corners Lewis substitutes single pieces of solid glass. The Lewis corners were not intended to perform any new office. They were of the ordinary form, and the shield was used in the ordinary way. Gordon's invention consists in corners of a peculiar form, and performing a new purpose. The novelty of Lewis' corners is the material of which they are made. Gordon's corners may be made of a variety of substances, but it is required that they shall be of a peculiar form. Lewis' corners are suitable for the photographic plate frame as ordinarily used. Gordon's corners require the frame to be made especially for them. The outline of the opening of the ordinary plate frame is that of a photographic plate, viz., oblong, whereas Gordon's corners are only useful in a frame with a square opening. The purpose of Gordon's invention is to permit the changing of the plate from a vertical to a horizontal presentation, or vice versa, without a special adjustment or the plate holder. Lewis' invention has no such purpose in view, and cannot be made to effect it. I find no points of agreement between the two inventions, in their nature, or construction, or purpose.” On cross-examination, being shown a facsimile of the model of the patent for the Lewis invention, and being asked whether he does not find in the corners “studs or projections which would enable the operator to change a plate from a horizontal to a perpendicular position, assuming that such studs were on all four corners, he replies: “I do not” “21 Cross-Q. Why not? A. The studs do not project enough to make a sufficiently firm support, and they are not in the position which the change of plate requires. The studs in this exhibit were not intended for any such purpose, cannot be used for it, and do not suggest it. To make studs suitable for such a purpose, the frame must have a square opening, whereas, in this case, it is oblong, and the distances between the studs must be very accurately adjusted. When these conditions are complied with, the device becomes substantially Gordon's. 22 Cross-Q. If this opening were square, and the studs more projecting, would it not then be Gordon's? A. Not necessarily. The studs of the exhibit are intended to be supports of the plate on which it is laid. If the conditions of Gordon's device were complied with, the adjacent studs would be placed at a distance from each other precisely the width of the plate, and the plate, when used in the frame, would not rest on the tops of the studs, as is evidently intended in the Exhibit No. 4. 23 Cross-Q. Assuming the opening to be square, and lines to be drawn from the inner side of the bottom stud to the inner side of the top stud, would not these lines, together with the the top and bottom of the frame, form an oblong parallelogram? A. Yes. 24 Cross-Q. And, if similar lines were drawn across the opening from stud to stud, would not these lines, with the side of the frame, constitute an oblong parallelogram? A. They would. 25 Cross-Q. And, if the opening were square, would not these two oblong parallelograms be equal? A. They would, provided the studs were symmetrically placed, and placed in the diagonals of the square. But Lewis' patent does not require any such accurate placing of the studs. Lewis' invention requires only that they shall be so placed that the plate may rest on them.” On his re-direct examination, he testified thus: “;26 Re-D. Q. In your answer to the 23d Cross-Q., have you not assumed, also, that the distances between the sides of the studs upon each side of the frame were equal? A. Yes; I assumed that 27 Re-D. Q. Please state the differences between the Gordon and the Lewis invention, so far as the arrangement or adjustment of the studs or projections in the corners is concerned? A. The office of the stud, in the Lewis invention, is to form a support for the frame. The plate rests upon the studs, and keeps the face away from contact with any other part of the frame. It is required that 776the studs shall have precisely the same height, but the amount of this height is not very material. It would ordinarily be made some fraction of the thickness of the plate. The precise location of these studs in reference to each other is, also, not material. It is only required that they shall be placed within the boundary of the plate. The figure which would be formed by the lines joining the adjacent ones might be a parallelogram, or a figure in which no two sides or angles were equal. The opening of the plate frame of the Lewis invention is of the form of the plate, and, of course, is generally an oblong parallelogram. Now, to prepare studs in accordance with the Gordon invention, the frame opening is, of necessity, square, and the side of this square is the length of the plate. The studs must be so placed that the edges of adjacent studs shall be distant from each other the width of the plate. The height of the stud should be somewhat more than the thickness of the plate, but it is not at all necessary. The studs should have the same height. In both inventions, the plate is kept from sliding in the focusing frame by the edges of the corners. In use, in the Lewis invention, the plate rests on the tops of the studs, while, in Gordon's, the plate rests on the bottoms of the corners. In the Lewis invention, it is not necessary that the bottom surfaces of the corners shall be in the same plane, whereas, in Gordon's, it is absolutely essential. In the Lewis invention, the plate rests on the tops of the studs, while, in the Gordon, the plate rests against the edges of the studs. The Lewis studs prevent a movement in a direction perpendicular to the plane of the plate, while, in the Gordon, they prevent movement in the plane of the plate. I do not think it possible that the Lewis invention could be constructed by any chance so as to comply with the conditions of Gordon's invention, nor do I think it likely in any way to suggest Gordon's invention to any person unacquainted with the latter.” The contention on the part of the defendants is, that, while there is nothing in the Lewis patent which suggests the use of the studs for the purpose of Gordon's invention, yet a plate could be supported by those studs in such a manner that oblong pictures could be taken, either vertically or horizontally; that, if so, it makes no difference whether Lewis thought of doing it or not; and that, if the Lewis structure is capable of the use to which the plaintiff's structure is put, it is the same thing. The complete answer to the Lewis structure is, that there is nothing in the patent which requires that the studs should be located, with reference to each other, in such manner that the figure formed by the lines joining the adjacent studs shall be a parallelogram, which is an absolute necessity in the Gordon invention, as described. The matter is clearly explained by Professor Seeley, and there is nothing in the opposing evidence that meets his view.

The patent to John Stock, of December 1st, 1857, for a “photographic plate holder,” is introduced by the defendants. But no witness testifies that the plaintiff's invention is found in it and the contrary is shown by Professor Seeley. The burden of proof is on the defendants to establish, by satisfactory evidence, the prior existence of the corners in Stock No. 1 and Stock No. 2. They have failed to do so, in my judgment. The unreliable nature of John Stock's testimony, the denial of his sales of the corners by the persons to whom he says they were sold, the unconvincing character of the testimony of Boch, Loehr and Jacob Stock, on the whole evidence, and the fact that, after the alleged making by John Stock of Stock No. 1 and Stock No. 2 he took out his patent of December, 1857, and described nothing of the kind, lead to the conclusion that this branch of the defence is not established. The nature of the invention set forth in that patent was making a plate holder fitted with sliding pieces, capable of being moved in or out to accommodate any sized glass or plate, said pieces being provided with suitable recesses and flanches to receive and support the glass or plate. The existence of the Exhibit Anthony No. 1 in the United States is not carried back to a date earlier than August 1st, 1858. The testimony is satisfactory to show that Gordon made his invention before that date.

It is urged for the defendants, that, as the patent had expired when this suit was brought, and no injunction could then be granted in it, and the bill is not a bill of discovery, the court has no jurisdiction to award an account, and, therefore, cannot take cognizance of the suit, as a suit in equity. Perhaps the bill is not to be regarded as a bill to obtain a discovery by answer to the bill, because the defendants are not, under the rule promulgated at the December term, 1850, amending rule 40 in equity, specially and particularly interrogated upon any statement in the bill. The bill states that the defendants' gains and profits from the manufacture and sale of the invention, in infringement of the plaintiff's rights, have been about $20,000, and prays “that the defendants may be required to make a disclosure of all such gains and profits.” It does not allege that the plaintiff cannot ascertain, without such disclosure, what such gains and profits are. On the other hand, no disclosure of gains and profits is necessary to establish the plaintiff's right to a decree for an accounting, such as is usually given on an adjudication in favor of the plaintiff on a final hearing, on pleadings and proofs, in a suit in equity on a patent. Such disclosure is an incident of the accounting, and, in a decree for an accounting a provision is inserted that the defendants attend before the master and produce their books and papers and submit to an examination respecting their gains and profits. Such examination of an accounting party is provided for by rule 79 in equity. The disclosure or discovery 777prayed for in the present bill is such a disclosure on an accounting. No discovery is prayed to establish the plaintiff's right of action to a decree for an accounting. That is established otherwise. Therefore, in no proper sense is the bill a bill of discovery or a bill praying a discovery.

In Nevins v. Johnson [Case No. 10,136], in this court, in 1853, before Mr. Justice Nelson and Judge Betts, the bill was filed after the patent had expired. It charged that the defendants had infringed, and “had realized great profits therefrom, and prayed a discovery of the particulars and extent of the use of the improvement, and that an account might be taken of the profits.” It was, in substance, like the present bill. It was demurred to, for want of equity, on the ground assigned, that there was a complete and adequate remedy at law in the case, and that a court of equity had no jurisdiction of it, because the term of the patent had expired before the suit was commenced and no injunction could be granted. But the court held, that, under the statute then existing (Act July 4, 1836; 5 Stat. 124, § 17), jurisdiction in equity was conferred upon the court, irrespective of the right of the patentee to an injunction. The present bill was filed in 1873, when section 55 of the act of July 8, 1870 (16 Stat. 206), was in force, the language of which, in respect to the subject in hand, was, in substance, the same as that of section 17 of the act of 1836, and the provisions of which are now found in sections 629, 711, and 4921 of the Revised Statutes. The cases of Sickels v. Gloucester Manuf'g Co. [Case No. 12,841]; Imlay v. Norwich & W. R. Co. [Id. 7,012]; Smith v. Baker [Id. 13,010); Jordan v. Dobson [Id. 7,519]; and Howes v. Nute [Id. 6,790],—recognize the rule as laid down in Nevins v. Johnson [supra]. In some of those cases the bill was filed before the patent expired and the decree was made after it expired.

In Draper v. Hudson [Case No. 4,069], before Judge Shepley, in 1873, the bill was for an injunction and an account, on a patent. The defendant died pending the suit and his executor was made defendant. No discovery was prayed against the executor, and there was no proof of infringement by him. The case is a difficult one to understand. There were two claims in the patent, which was a reissued patent. The court held that no infringement of the first claim, after the reissue, was shown, and that the second claim was void. A dismissal of the bill would seem, therefore, to have been necessary. Yet the court went on to say, that, as there could be no injunction against the original defendant, who was dead, and none against the executor, because he had not infringed, the right to an account failed, because the right to an injunction and a discovery failed. English cases were cited and the court added: “Although the jurisdiction of the circuit court in equity, in patent causes, rests upon statute provisions, it is to be exercised according to the course and principles of courts of equity; and, the supreme court of the United States having decided, in Stevens v. Gladding, 17 How. [58 U. S.] 455, that ‘the right to an account of profits is incident to a right to an injunction, in copy and patent-right cases,’ it would seem to follow, that, in a case like the present, where the title to equitable relief fails, the general rule of equity applies, that the incidental relief fails also.” The bill was dismissed, without costs. The views of Judge Shepley appear to have been based on what he understood to have been decided in Stevens v. Gladding [supra]. That was a bill in equity founded on the infringement of a copyright. The supreme court held that there had been an infringement. The bill prayed for an injunction and for general relief, but did not pray for an account, nor was an account stated in the answer. The question raised was, whether there ought to be a decree for an account. Of course, the plaintiff was entitled to a decree for an injunction. The point considered was, whether the plaintiff could have a decree for an account when he had not prayed for it. The court held that, as he was entitled to an injunction, he could have an account of profits, as an incident, and, also, that, as the bill stated a proper case for an account, one could be ordered under the prayer for general relief. The case does not decide, nor does it follow from it, that where, as here, the plaintiff states a case for an account, and prays for an account, and the defences are overruled, he cannot have an account, even though not entitled to an injunction. The weight of authority in this country is in favor of the right to an accounting, in a case like the present.

The record shows that the defendants put in evidence the record of certain proceedings in a suit brought by them in the supreme court of New York, against the plaintiff. Such evidence was put in in November, 1874. No objection was taken to it at the time, as not put in in season, or as not set up in the answer, or for any other cause. The record states that it was put in evidence, and that the seven papers constituting such proceedings were marked as exhibits for the defendants. On the 30th of June, 1875, and not before, the record states that the “complainant's counsel gives notice that he will move, before the hearing, to strike from the record” the said seven exhibits. The record states no reason as a ground for the notice or for the motion. At the hearing such motion was made, on the ground that no defence based on such proceedings is set up in the answer.

The proceedings show that the defendants brought a suit against the plaintiff, in the state court, in 1864, to recover a debt. Judgment was had in May, 1866. On the 12th of October, 1866, in proceedings supplementary to execution on said judgment, one Beamish was appointed by said court receiver “of all and singular the debts, property, equitable interests, rights and things in action of 778Ebenezer Gordon,” the plaintiff, and he was ordered to execute and deliver an assignment of the same to said receiver. It does not appear that any such assignment was ever executed. On the 4th of August, 1874, the receiver presented a petition to the state court, alleging, that, by virtue of his appointment and of his having given the requisite bond, he “became vested with all the estate, property and interests of the said Ebenezer Gordon, and, among others, the invention, patent, letters patent and patent-rights;” that Gordon, on the 12th of October, 1866, owned the said patent of October 19th, 1858, and the invention, patent and patent-right for which it was issued; that it was for the interest of the trust, “that all the right, title and interest of the said Ebenezer Gordon in and to the said invention, patent, letters patent and patent-rights,” at the time of the appointment of said receiver, and all the right and title and interest of said Gordon therein at any time since such appointment, and all the said Gordon's “right, title and interest in and to all and any claims under the said invention, patent, letters patent and patent-right,” should be sold at auction to the highest bidder. It prayed for an order authorizing such sale. On the same day, an order was made by said court, authorizing the sale at public auction by said receiver, for cash, on a specified notice, of everything which the receiver had so petitioned for leave to sell, and ordering that, on such sale being made, the receiver execute to the purchaser an assignment to vest the said property and interest in said purchaser. The record shows that the specified notice was given, and that the receiver sold at public auction, for $200, to the defendants in this suit, who were the highest bidders, the property and interests mentioned in said order of sale; that he reported such sale to said court; that said court made an order, on the 21st of August, 1874, that the report be confirmed and that he execute to the purchasers an assignment to vest the property and interests so sold in them; that on the same day he executed and delivered to said purchasers an assignment of said property and interests, which assignment specifies, as among the assigned property, “all the said Ebenezer Gordon's right, title and interest in and to all and any claims under the said invention, patent, letters patent and patent-right;” that he reported to the court, on the same day, that he had done so, and had received from the purchasers the $200 purchase-money, and how he had disposed of part of it; that the court, on the next day, made an order confirming said report as to said assignment; that, on the latter day, the receiver reported to the court how he had disposed of the rest of the purchase-money; and that the court, on that day, confirmed said report.

The defendants contend, that, by virtue of said proceedings and said assignment any right which the plaintiff had to recover against them for an infringement of the patent sued on has become vested in the defendants. Under sections 11, 14, and 17 of the act of July 4, 1836 (5 Stat. 121, 123, 124), it was always held, that no one could bring a suit, either at law or in equity, for the infringement of a patent in his own name alone, unless he were the patentee, or such an assignee or grantee as is mentioned in the 11th and 14th sections of that act. The provision in section 36 of the act of July 8, 1870 (16 Stat. 203), in regard to the assignments of patents and of interests therein, now embodied in section 4898 of the Revised Statutes, is not different from that found in section 11 of the act of 1836. The provisions in sections 53 and 59 of the act of 1870, in regard to suits in equity and at law for the infringement of a patent now embodied in sections 629, 711, 4919, and 4921 of the Revised Statutes, are hot different from those found in sections 14 and 17 of the act of 1836. These provisions were considered by this court in the case of Nelson v. McMann [Case No. 10,109], Under them no person can bring a suit for profits or damages for infringement who is not the patentee or such an assignee or grantee as the statute points out. A claim to recover profits or damages for past infringement cannot be severed from the title by assignment or grant, so as to give a right of action for such claim, in disregard of the statute. The profits or damages for infringement cannot be sued for except on the basis of title as patentee, or as such assignee or grantee, to the whole or a part of the patent, and not on the basis merely of the assignment of a right to a claim for profits and damages, severed from such title. Therefore, if, in the present case, no such assignment or grant has been made to the defendants as the statute contemplates, they could not bring suit, in their own names, under the assignment made to them, to recover any claims, profits or damages for infringement which belonged to Gordon, nor can they use the assignment as a defence against any such claims existing against themselves in favor of Gordon. In this case there has been no assignment executed by Gordon. The right claimed by the defendants rests, therefore, wholly on a transfer by operation of law. In Stephens v. Cady, 14 How. [55 U. S.] 528, it was strongly intimated by the supreme court, that an assignment of a copyright by opertion of law, unaccompanied by an assignment made by the owner, vests no title. In Stevens v. Gladding, 17 How. [58 U. S.] 447, the same court suggests that there would be great difficulty in assenting to the proposition that patent-rights and copyrights are subject to sale under the process of state courts. In Ashcroft v. Walworth [Case No. 580], it was held, that the title of an insolvent debtor to, or his interest in, a patent, does not pass to his assignee in insolvency, by an assignment of his property made by a 779judge under the insolvency law of Massachusetts. This decision was made on the ground that the assignee in insolvency acquired no title, because the conveyance was not such an one as was contemplated by section 11 of the act of 1836, namely, a written instrument signed by the owner of the patent and duly recorded. This seems to be a correct view, and it follows that the defendants acquired no right to anything which they can set up as a defence to the plaintiff's claim.

It is held (Moore v. Marsh, 7 Wall. [74 U. S.] 522), that the assignment of a patent does not carry with it a transfer of the right to damages for an infringement committed before such assignment. It is not at all clear that the transfer of the “claims” which the assignment in the present case transfers, can be construed to cover claims for past infringements. Dibble v. Augur [Case No. 3,879].

If the defence under the receivership were held to be available in respect to the whole or any part of the claim of the plaintiff, the defendants would, probably, on the facts in regard to the putting in evidence of the proceedings in the state court, be held to be entitled now to file a supplemental answer setting up such proceedings; but that question does not now arise. There must be a decree for the plaintiff, for an account of profits and damages.

1 [Reported by Hon. Samuel Blatchford, Circuit Judge; reprinted in 4 Ban. & A. 248; and here republished by permission.]

This volume of American Law was transcribed for use on the Internet

through a contribution from Google.